SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

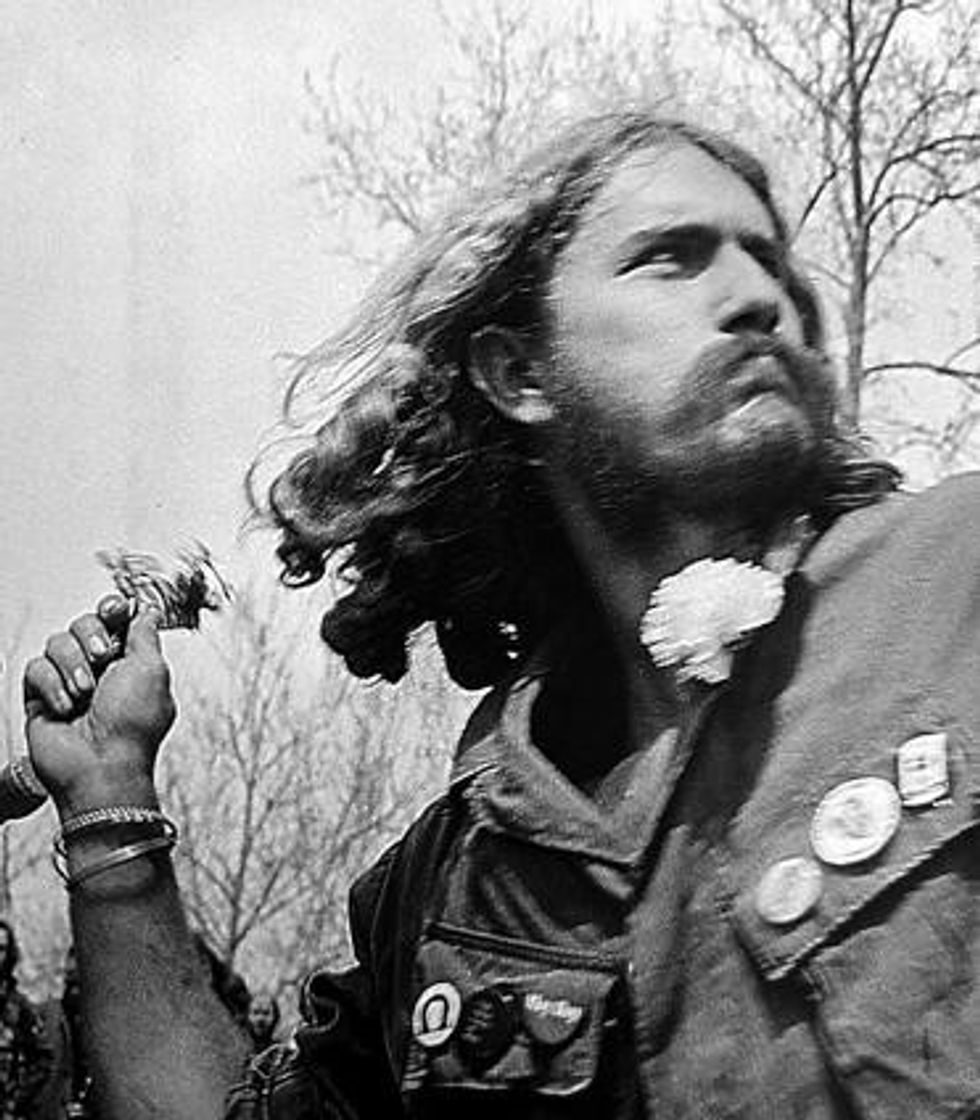

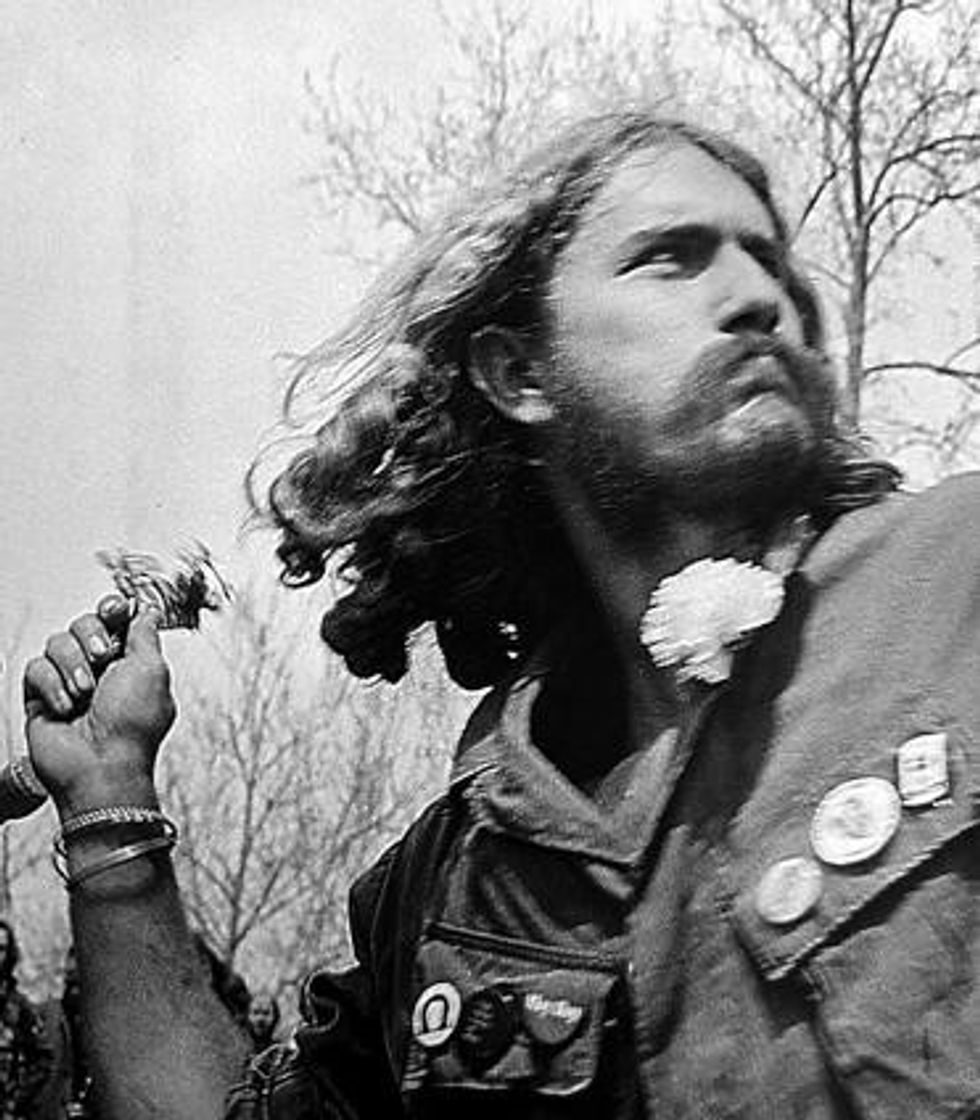

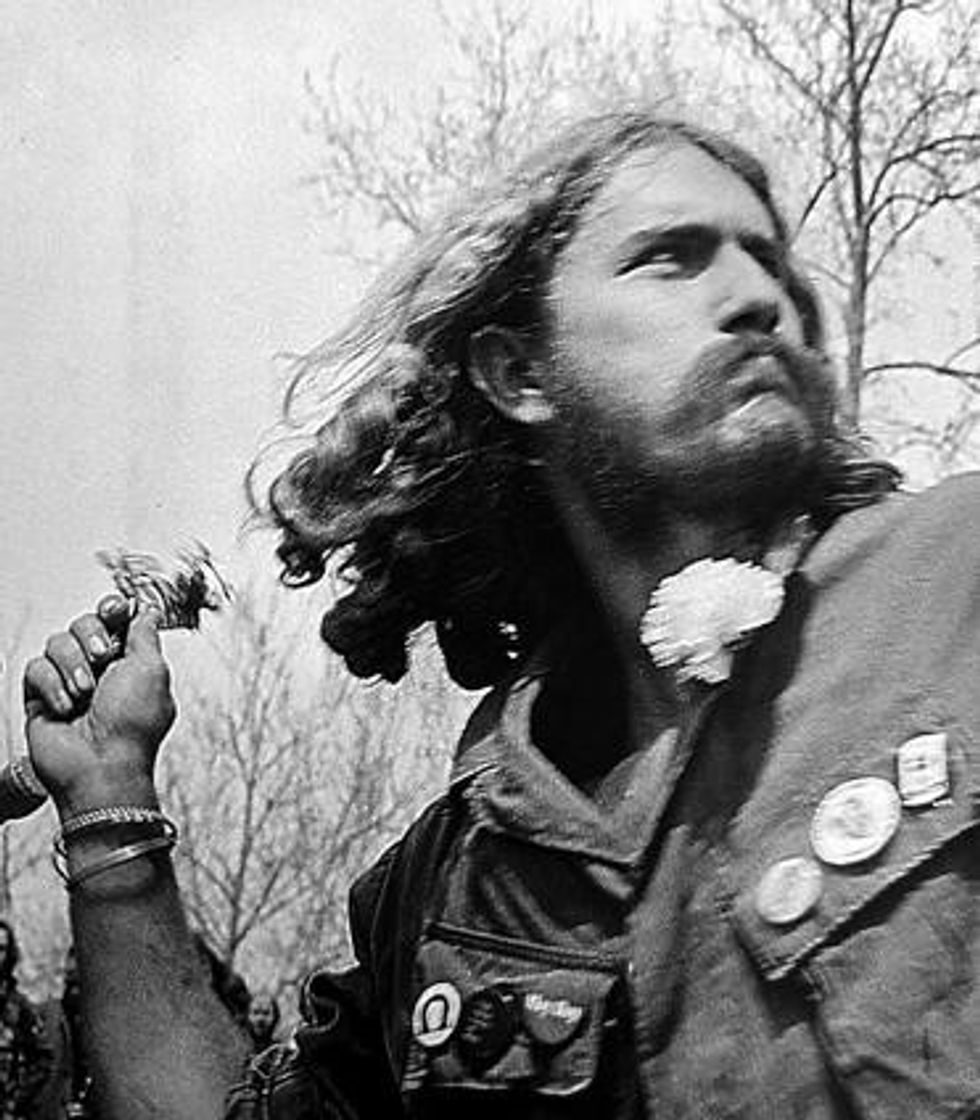

Vietnam Veterans Against the War participate in the Home With Honor parade in Manhattan, New York City, New York, which honored Prisoners of War and veterans returning from the Vietnam War, and also prompted counter-protests by groups opposed to the war, March 31, 1973.

The VVAW took the lead in influencing, orchestrating, and augmenting opposition to the Vietnam War that eventually contributed to bringing it to its ignominious conclusion.

Veterans have and continue to play, an important role in instigating social and political change in this country. One such group of veterans is the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, or VVAW: a movement of military veteran activist who, while struggling to heal from the psychological, emotional, and moral injuries of war, demanded through protests and demonstrations that our leaders fulfill their obligation to help veterans address their physical and mental health challenges, find alternative resolutions to conflict, and to bring an immediate end to the war in Southeast Asia.

Soldiers coming home from war joined VVAW members in speaking out through their poetry, short stories, novels, memoirs, and testimony to Congress and the American people about their experiences in war and afterward. Their intention was to educate the public about the horrific battlefield conditions they experienced while fighting America’s war in Vietnam, the nightmarish atrocities against innocent civilians that in many cases they may have committed, and the lack of care and horrendous conditions they suffered at Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals upon their return home.

Should you have the privilege one day to meet members of VVAW or other activist veterans, do take the time to thank them for their service.

Beset with grief and shame about what they did in the war and incensed about how they were treated upon their return, the veterans felt betrayed and abandoned by the government that sent them to war. It quickly became apparent to them that if healing was to occur and the illegal and immoral war to end—comrades were still killing and dying in Vietnam—the only recourse available was to work together to seek relief from their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries, later termed post-traumatic stress disorder and moral injury; to press the government to fulfill its obligation to provide adequate healthcare programs at the VA; and to educate the public about the true nature of war and what was being done in their names.

Because all war entails the injuring and killing of other human beings, the destruction of property, and the environment, any resort to war is at a minimum morally and legally problematic and requires moral and legal analysis and justification. Members of the military do not abdicate their moral and legal agency and hence their responsibility for their actions upon enlistment or conscription. Consequently, soldiers have the grave responsibility to evaluate, morally and legally, the war they are being ordered to fight. This is admittedly no easy task given the proclivity of political and military leaders to deceive the public by claiming aggression, national security, etc. Should the moral and legal value of the war be ambiguous, unnecessary, or determined to be unjust, a soldier must refuse to obey the order to fight and become a war resistor or conscientious objector. Soldiers are obligated only to obey just orders, and the order to fight in an unjust war is an illegal and immoral order. The government that issues such orders is guilty of war crimes.

Tragically, having been thoroughly indoctrinated and conditioned during basic training or boot camp to unquestioningly obey orders to fight and to kill, many members of the military had succumbed to the social pressures of the warrior culture and their military superiors to complete their deployments despite having serious doubts regarding the morality and legality of the war. Further, to warriors on the battlefield struggling to survive the next improvised explosive device (IED) or suicide bomber, war’s negative effects are pervasive and cumulative. Everyday living in a war zone is a netherworld of horror and insanity in which law and morality become a liability, and atrocity—moral transgression—a matter of perspective. Life amid the violence, death, horror, trauma, anxiety, and fatigue of war erodes moral being, undoes character, and reduces decent men and women to savages capable of incredible cruelty that would never have been thinkable before being conditioned to kill and sacrificed to war. Moral transgressions in such an environment are commonplace and not isolated aberrant occurrences prosecuted by a few deviant individuals, as militarists would have us believe. Rather, they are intrinsic to the nature and the reality of wars, what psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton appropriately described as “atrocity producing situations,” the inevitable consequence of first being conditioned to kill and then enduring the prolonged, life-threatening, and morally untenable conditions of the battlefield.

Consequently, many warriors perhaps even most, either while still in theater or upon their return home, suffered devastating life-altering, long-enduring trauma-related injuries—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder—as well as the shame, guilt, loss of self-respect, alienation, etc., consequent to having transgressed deeply held moral beliefs–Combat Related Moral Injury.

I fear I am no longer alien to this horror.

I am, I am, I am the horror,

I have lost my humanity

And embraced the insanity of war.

The Monster and I are one...

The Transformation is complete

And I can no longer return.

Mea culpa,

Mea culpa,

Mea maxima culpa.

During World War II, more than half a million service members became psychiatric casualties due to their prolonged exposure to combat. Further, some 40% of medical discharges during the war were due to psychiatric conditions. To ensure uniformity of diagnosis and adequate treatment, the War Department Technical Bulletin, Medical 2030, recognized that following combat, soldiers may develop neurotic or psychotic reactions, a diagnosis it termed “combat exhaustion.”

In 1952, though continuing to recognize combat as a cause of a broad range of disabling reactions to traumatic stress, the American Psychological Association’s (APA) first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), modified the War Department Technical Bulletin’s nomenclature, substituting ““Gross Stress Reaction” for the Combat Exhaustion diagnosis.To remedy this high rate of psychiatric injuries suffered by soldiers during World War II, and to maintain maximum warrior effectiveness, several treatment modifications and changes in deployment protocols were implemented following the war.

To fulfill President Lincoln’s Promise to care for those who have served in our nation’s military and for their families, caregivers, and survivors. —Mission statement of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The United States Government’s obligation to its veterans under the enlistment contract is to provide access to quality medical treatment including mental health services and disability compensation. Vice President Kamala Harris recently reasserted this obligation during a Veterans Day address at Arlington National Cemetery.

Since the founding of the United States, service members have defended the nation. In return, the nation has an obligation to take care of those same veterans.

Co-conspiring with the government to focus on the individual’s premilitary history, ignoring the effects the war experience may have had upon the veterans, the APA removed the diagnosis of Gross Stress Reaction from its revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders II in 1968

This obligation extends beyond the soldiers’ time in military service and entails providing ongoing support and resources to help veterans reintegrate into society, address any physical or mental health challenges, and ensure their overall well-being.

During the initial months of the Korean War, acute psychiatric casualties remained unacceptably high—250 per 1,000 men per year. As the treatment and deployment modifications noted above were eventually implemented in Korea and then in Vietnam, the numbers improved significantly. Tragically, however, these improving numbers—acute psychiatric casualties dropped to approximately 11.5 per 1,000 men per year during the Vietnam War—and the fact that the symptoms presented by returning Vietnam Veterans occurred some 9-30 months after demobilization, provided the impetus for the VA, the government agency charged with the care and treatment of veterans, to ignore or misdiagnose their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries claiming them to be nonservice connected, unrelated to the their experiences in Vietnam. Consequently, the government accepted no responsibility to treat or compensate the veterans for what they alleged to be preexisting conditions, profound though they may be.

Co-conspiring with the government to focus on the individual’s premilitary history, ignoring the effects the war experience may have had upon the veterans, the APA removed the diagnosis of Gross Stress Reaction from its revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders II in 1968, curiously the same year as the Tet Offensive. This tragic omission left the returning Vietnam Veterans without a codified psychiatric diagnosis with which to explain the causal relationship between their service in war and their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries.

The programming and conditioning Vietnam era recruits were subjected to in boot camp and basic training, later reinforced by the “ambiguities” posed by the guerilla warfare they experienced in Vietnam, diminished the soldiers’ moral being and encouraged brutality and eventually atrocity, causing them ultimately to view themselves not as noble warriors but as beasts and murderers. As the true nature of demythologized war became apparent, Vietnam veterans realized that they and the American people had been lied to, that their being in Vietnam had nothing to do with preserving the freedom either of Americans or of the Vietnamese, that the “enemy” they were killing and that were killing them were not terrorists or ideologues bent upon world domination as they had been told, but nationalists and freedom fighters struggling against yet another in a long series of colonialists, invaders, and occupiers. Saddled with fighting a war of attrition with weapons that were defective and unreliable, often resulting in their injury or death, the veterans felt betrayed while in Vietnam and abandoned upon their return home.

Understandably distrustful of government bureaucracy, disappointed with the failure of the government to end the war in Vietnam, dismayed with “establishment” psychiatric services, and frustrated with having their injuries ignored or misdiagnosed by the VA, Vietnam veterans saw no other recourse than to form a self-help group, an activist organization, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, intending to “get their heads together,” fend for themselves, and “structure their own solutions.”

In December 1970, VVAW members from their New York City headquarters began their peer support network, initially with no professional clinical involvement. Termed “rap groups,” these makeshift meetings were intended as a venue for VVAW members to share their war experiences; express grievances; work through the guilt, rage, depression, and alienation; and build community based upon their common experiences during the Vietnam War. As the rap groups progressed and trust increased, members shared honestly, felt less burdened, and became better able to connect with the outside world. Jan Barry, one of VVAW’s founders, after attending a lecture on the Hiroshima survivors by noted anti-war Harvard psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, invited Lifton to join the sessions, not as a leader or facilitator, but as a “resource” person and observer who could help the group focus and, hopefully, draw coherent conclusions about their experiences. In his letter of invitation, Barry succinctly described the veterans who would be participating in the rap groups and what they hoped to accomplish as an organization:

Guys are hurting. They’re opposed to the war, and they want to deal with their hurt, and they don’t want to go to the VA. They also want to make known to the world what war is like. Can you help us in some way? (Nicosia, 2001, p. 161)

Together with New York University psychiatrist Chaim Shatan, Lifton attended the rap sessions, the goals of which became (1) psychological transformation (healing), (2) publicizing the veteran’s destructive personal experiences to educate the public regarding the realities and the human cost of the war in Vietnam, (3) appealing to the consciences of the American public regarding the immorality of the war, (4) encouraging activism to alter the political policies that sustained the war, and finally (5) motivating government leaders to immediately end the war, bring all the soldiers home, and provide effective treatment for their physical, psychological, emotional, and moral injuries upon their return.

Lifton and Chatan quickly recognized that what they had become involved in was a new “nonhierarchical form of dialogic therapy” in which the issues and concerns they discussed were common to the war experience and did not fit any standard DSM diagnostic category. Through the courage, transparency, and persistence of the VVAW rap group participants and the professionalism, knowledge, efforts, and dedication of the VVAW psychiatrists who championed their cause, the characterization of returning veterans began to transition from the stigmatizing stereotypes of drug addicts, baby killers, ticking time bombs, and junkies to psychologically, emotionally, and morally injured—Post-Vietnam Syndrome.

In addition to establishing the symptomatology and etiology of what later became known as post-traumatic stress disorder, another important outcome of the rap group experience was the correlation between the two primary goals of VVAW, healing and bringing an end to the war. For healing to occur more than just discussion, the communalization of grief, was required. To heal, veterans must become engaged, in what I have termed elsewhere as “doing penance for the sacrilege of war.” That is, engaging in political and social activism to end the war and to right the wrongs they had committed—protest and demonstration—became inseparable and integral to the healing process.

To men who have been steeped in death and evil beyond imagination, a “talking cure” alone is worthless. And merely sharing their grief and outrage with comrades... is similarly unsatisfying. Active participation in the public arena, active opposition to the very war policies they helped carry out, was essential. (Shatan, The Grief of Soldiers, 1973)

Hence the importance of the integration of VVAW’s rap groups with their activism. Of healing—coming to grips with their experiences in war—with educating the public about war’s realities through protest and demonstration. Through guerilla theater, VVAW members, dressed in combat regalia, acted out the detainment and abuse of civilian spectators. During “Operation Dewey Canyon III,” arguably one of VVAW’s most successful actions, more than 1000 veterans, after saying their name, their units, and making a statement about the illegality of the war, threw their medals over the fence surrounding the Capitol building.

By throwing onto the steps of Congress the medals with which they were rewarded for murder in a war they had come to abhor, the veterans symbolically shed some of their guilt. In addition to their dramatic political impact, these demonstrations have profound therapeutic meaning. Instead of acting under orders, the vets originated action on their own behalf to regain control over events—over their lives—that were wrested from them in Vietnam. (Shatan, The Grief of Soldiers, 1973)

Despite the plethora of evidence to the contrary, many Americans continue to embrace, even until today, the mythology of the conflict in Vietnam as a just war against communist aggression. While quick to thank veterans for their “service” and alleging gratitude for their sacrifices, these self-proclaimed patriots have little understanding of the conditioning Vietnam era veterans endured during basic training and boot camp to increase their lethality—their ability to kill a dehumanized “enemy” in a guerilla and counterinsurgency war. Nor do they appreciate how the long-term effects of this training, reinforced by life amid the violence, death, horror, trauma, anxiety, and fatigue of war, eroded the warriors’ moral being, undid character, and reduced decent men and women to savages making the likelihood of atrocity inevitable. Most tragically, they were and in many cases remain indifferent to the devastating psychological, emotional, and moral injuries veterans suffered consequent to their experiences in the war.

Since, at its height, VVAW had an estimated 25,000 members, only a fraction of the 2.5 million veterans who served in Vietnam, these critics allege they received attention completely out of proportion to their numbers and their importance. Further, despite their sacrifices and all that they have and continue to accomplish, militarists and those who seek to continue to benefit from war have worked diligently to condemn members of VVAW and other veteran activist groups such as About Face:Veterans Against War, formally the Iraq Veterans Against the War, as traitors to this nation, to their fellow veterans, and to portray their work as misguided and as an existential threat to America’s survival. As a result, many in this nation fail to appreciate VVAW’s contribution and recognize the debt it owes its members.

While suffering the physical, psychological, emotional, and moral injuries sustained in the war, VVAW members displayed the courage and forthrightness to realize and “confess” to being instruments of this nation’s illegal and immoral war during its Winter Soldier Hearings. Through their testimony and truth-telling, those who would listen were educated about what war does to those who fight it and the crimes—the atrocities—that were committed in their names. Through their activism—guerilla theater, Dewey Canyon III, etc.—the public learned about what transpires in guerilla and counterinsurgency war. Through their efforts to effect healing—their unique and effective therapeutic “rap groups”—in which they involved and educated dedicated clinical professionals—Robert Jay Lifton, Chaim Shatan, among others—VVAW members were instrumental in bringing recognition and attention to trauma-related and moral injuries—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Combat Related Moral Injury. By so doing, a codified psychiatric diagnosis was again recognized and included in the revised edition of the DSM III with which to explain the symptomatology and etiology of the injuries suffered not only by soldiers in war but by first responders and victims of natural disasters, rapes, etc. Finally, through their activism and the attention they brought to the war, VVAW took the lead in influencing, orchestrating, and augmenting opposition to the American war in Vietnam that eventually contributed to bringing it to its ignominious conclusion.

So should you have the privilege one day to meet members of VVAW or other activist veterans, do take the time to thank them for their service, not for fighting some ill-conceived, immoral war, however, but for a lifetime of sacrifice and commitment to continuing their difficult and at most times thankless work for peace and social justice.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Veterans have and continue to play, an important role in instigating social and political change in this country. One such group of veterans is the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, or VVAW: a movement of military veteran activist who, while struggling to heal from the psychological, emotional, and moral injuries of war, demanded through protests and demonstrations that our leaders fulfill their obligation to help veterans address their physical and mental health challenges, find alternative resolutions to conflict, and to bring an immediate end to the war in Southeast Asia.

Soldiers coming home from war joined VVAW members in speaking out through their poetry, short stories, novels, memoirs, and testimony to Congress and the American people about their experiences in war and afterward. Their intention was to educate the public about the horrific battlefield conditions they experienced while fighting America’s war in Vietnam, the nightmarish atrocities against innocent civilians that in many cases they may have committed, and the lack of care and horrendous conditions they suffered at Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals upon their return home.

Should you have the privilege one day to meet members of VVAW or other activist veterans, do take the time to thank them for their service.

Beset with grief and shame about what they did in the war and incensed about how they were treated upon their return, the veterans felt betrayed and abandoned by the government that sent them to war. It quickly became apparent to them that if healing was to occur and the illegal and immoral war to end—comrades were still killing and dying in Vietnam—the only recourse available was to work together to seek relief from their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries, later termed post-traumatic stress disorder and moral injury; to press the government to fulfill its obligation to provide adequate healthcare programs at the VA; and to educate the public about the true nature of war and what was being done in their names.

Because all war entails the injuring and killing of other human beings, the destruction of property, and the environment, any resort to war is at a minimum morally and legally problematic and requires moral and legal analysis and justification. Members of the military do not abdicate their moral and legal agency and hence their responsibility for their actions upon enlistment or conscription. Consequently, soldiers have the grave responsibility to evaluate, morally and legally, the war they are being ordered to fight. This is admittedly no easy task given the proclivity of political and military leaders to deceive the public by claiming aggression, national security, etc. Should the moral and legal value of the war be ambiguous, unnecessary, or determined to be unjust, a soldier must refuse to obey the order to fight and become a war resistor or conscientious objector. Soldiers are obligated only to obey just orders, and the order to fight in an unjust war is an illegal and immoral order. The government that issues such orders is guilty of war crimes.

Tragically, having been thoroughly indoctrinated and conditioned during basic training or boot camp to unquestioningly obey orders to fight and to kill, many members of the military had succumbed to the social pressures of the warrior culture and their military superiors to complete their deployments despite having serious doubts regarding the morality and legality of the war. Further, to warriors on the battlefield struggling to survive the next improvised explosive device (IED) or suicide bomber, war’s negative effects are pervasive and cumulative. Everyday living in a war zone is a netherworld of horror and insanity in which law and morality become a liability, and atrocity—moral transgression—a matter of perspective. Life amid the violence, death, horror, trauma, anxiety, and fatigue of war erodes moral being, undoes character, and reduces decent men and women to savages capable of incredible cruelty that would never have been thinkable before being conditioned to kill and sacrificed to war. Moral transgressions in such an environment are commonplace and not isolated aberrant occurrences prosecuted by a few deviant individuals, as militarists would have us believe. Rather, they are intrinsic to the nature and the reality of wars, what psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton appropriately described as “atrocity producing situations,” the inevitable consequence of first being conditioned to kill and then enduring the prolonged, life-threatening, and morally untenable conditions of the battlefield.

Consequently, many warriors perhaps even most, either while still in theater or upon their return home, suffered devastating life-altering, long-enduring trauma-related injuries—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder—as well as the shame, guilt, loss of self-respect, alienation, etc., consequent to having transgressed deeply held moral beliefs–Combat Related Moral Injury.

I fear I am no longer alien to this horror.

I am, I am, I am the horror,

I have lost my humanity

And embraced the insanity of war.

The Monster and I are one...

The Transformation is complete

And I can no longer return.

Mea culpa,

Mea culpa,

Mea maxima culpa.

During World War II, more than half a million service members became psychiatric casualties due to their prolonged exposure to combat. Further, some 40% of medical discharges during the war were due to psychiatric conditions. To ensure uniformity of diagnosis and adequate treatment, the War Department Technical Bulletin, Medical 2030, recognized that following combat, soldiers may develop neurotic or psychotic reactions, a diagnosis it termed “combat exhaustion.”

In 1952, though continuing to recognize combat as a cause of a broad range of disabling reactions to traumatic stress, the American Psychological Association’s (APA) first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), modified the War Department Technical Bulletin’s nomenclature, substituting ““Gross Stress Reaction” for the Combat Exhaustion diagnosis.To remedy this high rate of psychiatric injuries suffered by soldiers during World War II, and to maintain maximum warrior effectiveness, several treatment modifications and changes in deployment protocols were implemented following the war.

To fulfill President Lincoln’s Promise to care for those who have served in our nation’s military and for their families, caregivers, and survivors. —Mission statement of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The United States Government’s obligation to its veterans under the enlistment contract is to provide access to quality medical treatment including mental health services and disability compensation. Vice President Kamala Harris recently reasserted this obligation during a Veterans Day address at Arlington National Cemetery.

Since the founding of the United States, service members have defended the nation. In return, the nation has an obligation to take care of those same veterans.

Co-conspiring with the government to focus on the individual’s premilitary history, ignoring the effects the war experience may have had upon the veterans, the APA removed the diagnosis of Gross Stress Reaction from its revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders II in 1968

This obligation extends beyond the soldiers’ time in military service and entails providing ongoing support and resources to help veterans reintegrate into society, address any physical or mental health challenges, and ensure their overall well-being.

During the initial months of the Korean War, acute psychiatric casualties remained unacceptably high—250 per 1,000 men per year. As the treatment and deployment modifications noted above were eventually implemented in Korea and then in Vietnam, the numbers improved significantly. Tragically, however, these improving numbers—acute psychiatric casualties dropped to approximately 11.5 per 1,000 men per year during the Vietnam War—and the fact that the symptoms presented by returning Vietnam Veterans occurred some 9-30 months after demobilization, provided the impetus for the VA, the government agency charged with the care and treatment of veterans, to ignore or misdiagnose their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries claiming them to be nonservice connected, unrelated to the their experiences in Vietnam. Consequently, the government accepted no responsibility to treat or compensate the veterans for what they alleged to be preexisting conditions, profound though they may be.

Co-conspiring with the government to focus on the individual’s premilitary history, ignoring the effects the war experience may have had upon the veterans, the APA removed the diagnosis of Gross Stress Reaction from its revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders II in 1968, curiously the same year as the Tet Offensive. This tragic omission left the returning Vietnam Veterans without a codified psychiatric diagnosis with which to explain the causal relationship between their service in war and their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries.

The programming and conditioning Vietnam era recruits were subjected to in boot camp and basic training, later reinforced by the “ambiguities” posed by the guerilla warfare they experienced in Vietnam, diminished the soldiers’ moral being and encouraged brutality and eventually atrocity, causing them ultimately to view themselves not as noble warriors but as beasts and murderers. As the true nature of demythologized war became apparent, Vietnam veterans realized that they and the American people had been lied to, that their being in Vietnam had nothing to do with preserving the freedom either of Americans or of the Vietnamese, that the “enemy” they were killing and that were killing them were not terrorists or ideologues bent upon world domination as they had been told, but nationalists and freedom fighters struggling against yet another in a long series of colonialists, invaders, and occupiers. Saddled with fighting a war of attrition with weapons that were defective and unreliable, often resulting in their injury or death, the veterans felt betrayed while in Vietnam and abandoned upon their return home.

Understandably distrustful of government bureaucracy, disappointed with the failure of the government to end the war in Vietnam, dismayed with “establishment” psychiatric services, and frustrated with having their injuries ignored or misdiagnosed by the VA, Vietnam veterans saw no other recourse than to form a self-help group, an activist organization, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, intending to “get their heads together,” fend for themselves, and “structure their own solutions.”

In December 1970, VVAW members from their New York City headquarters began their peer support network, initially with no professional clinical involvement. Termed “rap groups,” these makeshift meetings were intended as a venue for VVAW members to share their war experiences; express grievances; work through the guilt, rage, depression, and alienation; and build community based upon their common experiences during the Vietnam War. As the rap groups progressed and trust increased, members shared honestly, felt less burdened, and became better able to connect with the outside world. Jan Barry, one of VVAW’s founders, after attending a lecture on the Hiroshima survivors by noted anti-war Harvard psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, invited Lifton to join the sessions, not as a leader or facilitator, but as a “resource” person and observer who could help the group focus and, hopefully, draw coherent conclusions about their experiences. In his letter of invitation, Barry succinctly described the veterans who would be participating in the rap groups and what they hoped to accomplish as an organization:

Guys are hurting. They’re opposed to the war, and they want to deal with their hurt, and they don’t want to go to the VA. They also want to make known to the world what war is like. Can you help us in some way? (Nicosia, 2001, p. 161)

Together with New York University psychiatrist Chaim Shatan, Lifton attended the rap sessions, the goals of which became (1) psychological transformation (healing), (2) publicizing the veteran’s destructive personal experiences to educate the public regarding the realities and the human cost of the war in Vietnam, (3) appealing to the consciences of the American public regarding the immorality of the war, (4) encouraging activism to alter the political policies that sustained the war, and finally (5) motivating government leaders to immediately end the war, bring all the soldiers home, and provide effective treatment for their physical, psychological, emotional, and moral injuries upon their return.

Lifton and Chatan quickly recognized that what they had become involved in was a new “nonhierarchical form of dialogic therapy” in which the issues and concerns they discussed were common to the war experience and did not fit any standard DSM diagnostic category. Through the courage, transparency, and persistence of the VVAW rap group participants and the professionalism, knowledge, efforts, and dedication of the VVAW psychiatrists who championed their cause, the characterization of returning veterans began to transition from the stigmatizing stereotypes of drug addicts, baby killers, ticking time bombs, and junkies to psychologically, emotionally, and morally injured—Post-Vietnam Syndrome.

In addition to establishing the symptomatology and etiology of what later became known as post-traumatic stress disorder, another important outcome of the rap group experience was the correlation between the two primary goals of VVAW, healing and bringing an end to the war. For healing to occur more than just discussion, the communalization of grief, was required. To heal, veterans must become engaged, in what I have termed elsewhere as “doing penance for the sacrilege of war.” That is, engaging in political and social activism to end the war and to right the wrongs they had committed—protest and demonstration—became inseparable and integral to the healing process.

To men who have been steeped in death and evil beyond imagination, a “talking cure” alone is worthless. And merely sharing their grief and outrage with comrades... is similarly unsatisfying. Active participation in the public arena, active opposition to the very war policies they helped carry out, was essential. (Shatan, The Grief of Soldiers, 1973)

Hence the importance of the integration of VVAW’s rap groups with their activism. Of healing—coming to grips with their experiences in war—with educating the public about war’s realities through protest and demonstration. Through guerilla theater, VVAW members, dressed in combat regalia, acted out the detainment and abuse of civilian spectators. During “Operation Dewey Canyon III,” arguably one of VVAW’s most successful actions, more than 1000 veterans, after saying their name, their units, and making a statement about the illegality of the war, threw their medals over the fence surrounding the Capitol building.

By throwing onto the steps of Congress the medals with which they were rewarded for murder in a war they had come to abhor, the veterans symbolically shed some of their guilt. In addition to their dramatic political impact, these demonstrations have profound therapeutic meaning. Instead of acting under orders, the vets originated action on their own behalf to regain control over events—over their lives—that were wrested from them in Vietnam. (Shatan, The Grief of Soldiers, 1973)

Despite the plethora of evidence to the contrary, many Americans continue to embrace, even until today, the mythology of the conflict in Vietnam as a just war against communist aggression. While quick to thank veterans for their “service” and alleging gratitude for their sacrifices, these self-proclaimed patriots have little understanding of the conditioning Vietnam era veterans endured during basic training and boot camp to increase their lethality—their ability to kill a dehumanized “enemy” in a guerilla and counterinsurgency war. Nor do they appreciate how the long-term effects of this training, reinforced by life amid the violence, death, horror, trauma, anxiety, and fatigue of war, eroded the warriors’ moral being, undid character, and reduced decent men and women to savages making the likelihood of atrocity inevitable. Most tragically, they were and in many cases remain indifferent to the devastating psychological, emotional, and moral injuries veterans suffered consequent to their experiences in the war.

Since, at its height, VVAW had an estimated 25,000 members, only a fraction of the 2.5 million veterans who served in Vietnam, these critics allege they received attention completely out of proportion to their numbers and their importance. Further, despite their sacrifices and all that they have and continue to accomplish, militarists and those who seek to continue to benefit from war have worked diligently to condemn members of VVAW and other veteran activist groups such as About Face:Veterans Against War, formally the Iraq Veterans Against the War, as traitors to this nation, to their fellow veterans, and to portray their work as misguided and as an existential threat to America’s survival. As a result, many in this nation fail to appreciate VVAW’s contribution and recognize the debt it owes its members.

While suffering the physical, psychological, emotional, and moral injuries sustained in the war, VVAW members displayed the courage and forthrightness to realize and “confess” to being instruments of this nation’s illegal and immoral war during its Winter Soldier Hearings. Through their testimony and truth-telling, those who would listen were educated about what war does to those who fight it and the crimes—the atrocities—that were committed in their names. Through their activism—guerilla theater, Dewey Canyon III, etc.—the public learned about what transpires in guerilla and counterinsurgency war. Through their efforts to effect healing—their unique and effective therapeutic “rap groups”—in which they involved and educated dedicated clinical professionals—Robert Jay Lifton, Chaim Shatan, among others—VVAW members were instrumental in bringing recognition and attention to trauma-related and moral injuries—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Combat Related Moral Injury. By so doing, a codified psychiatric diagnosis was again recognized and included in the revised edition of the DSM III with which to explain the symptomatology and etiology of the injuries suffered not only by soldiers in war but by first responders and victims of natural disasters, rapes, etc. Finally, through their activism and the attention they brought to the war, VVAW took the lead in influencing, orchestrating, and augmenting opposition to the American war in Vietnam that eventually contributed to bringing it to its ignominious conclusion.

So should you have the privilege one day to meet members of VVAW or other activist veterans, do take the time to thank them for their service, not for fighting some ill-conceived, immoral war, however, but for a lifetime of sacrifice and commitment to continuing their difficult and at most times thankless work for peace and social justice.

Veterans have and continue to play, an important role in instigating social and political change in this country. One such group of veterans is the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, or VVAW: a movement of military veteran activist who, while struggling to heal from the psychological, emotional, and moral injuries of war, demanded through protests and demonstrations that our leaders fulfill their obligation to help veterans address their physical and mental health challenges, find alternative resolutions to conflict, and to bring an immediate end to the war in Southeast Asia.

Soldiers coming home from war joined VVAW members in speaking out through their poetry, short stories, novels, memoirs, and testimony to Congress and the American people about their experiences in war and afterward. Their intention was to educate the public about the horrific battlefield conditions they experienced while fighting America’s war in Vietnam, the nightmarish atrocities against innocent civilians that in many cases they may have committed, and the lack of care and horrendous conditions they suffered at Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals upon their return home.

Should you have the privilege one day to meet members of VVAW or other activist veterans, do take the time to thank them for their service.

Beset with grief and shame about what they did in the war and incensed about how they were treated upon their return, the veterans felt betrayed and abandoned by the government that sent them to war. It quickly became apparent to them that if healing was to occur and the illegal and immoral war to end—comrades were still killing and dying in Vietnam—the only recourse available was to work together to seek relief from their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries, later termed post-traumatic stress disorder and moral injury; to press the government to fulfill its obligation to provide adequate healthcare programs at the VA; and to educate the public about the true nature of war and what was being done in their names.

Because all war entails the injuring and killing of other human beings, the destruction of property, and the environment, any resort to war is at a minimum morally and legally problematic and requires moral and legal analysis and justification. Members of the military do not abdicate their moral and legal agency and hence their responsibility for their actions upon enlistment or conscription. Consequently, soldiers have the grave responsibility to evaluate, morally and legally, the war they are being ordered to fight. This is admittedly no easy task given the proclivity of political and military leaders to deceive the public by claiming aggression, national security, etc. Should the moral and legal value of the war be ambiguous, unnecessary, or determined to be unjust, a soldier must refuse to obey the order to fight and become a war resistor or conscientious objector. Soldiers are obligated only to obey just orders, and the order to fight in an unjust war is an illegal and immoral order. The government that issues such orders is guilty of war crimes.

Tragically, having been thoroughly indoctrinated and conditioned during basic training or boot camp to unquestioningly obey orders to fight and to kill, many members of the military had succumbed to the social pressures of the warrior culture and their military superiors to complete their deployments despite having serious doubts regarding the morality and legality of the war. Further, to warriors on the battlefield struggling to survive the next improvised explosive device (IED) or suicide bomber, war’s negative effects are pervasive and cumulative. Everyday living in a war zone is a netherworld of horror and insanity in which law and morality become a liability, and atrocity—moral transgression—a matter of perspective. Life amid the violence, death, horror, trauma, anxiety, and fatigue of war erodes moral being, undoes character, and reduces decent men and women to savages capable of incredible cruelty that would never have been thinkable before being conditioned to kill and sacrificed to war. Moral transgressions in such an environment are commonplace and not isolated aberrant occurrences prosecuted by a few deviant individuals, as militarists would have us believe. Rather, they are intrinsic to the nature and the reality of wars, what psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton appropriately described as “atrocity producing situations,” the inevitable consequence of first being conditioned to kill and then enduring the prolonged, life-threatening, and morally untenable conditions of the battlefield.

Consequently, many warriors perhaps even most, either while still in theater or upon their return home, suffered devastating life-altering, long-enduring trauma-related injuries—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder—as well as the shame, guilt, loss of self-respect, alienation, etc., consequent to having transgressed deeply held moral beliefs–Combat Related Moral Injury.

I fear I am no longer alien to this horror.

I am, I am, I am the horror,

I have lost my humanity

And embraced the insanity of war.

The Monster and I are one...

The Transformation is complete

And I can no longer return.

Mea culpa,

Mea culpa,

Mea maxima culpa.

During World War II, more than half a million service members became psychiatric casualties due to their prolonged exposure to combat. Further, some 40% of medical discharges during the war were due to psychiatric conditions. To ensure uniformity of diagnosis and adequate treatment, the War Department Technical Bulletin, Medical 2030, recognized that following combat, soldiers may develop neurotic or psychotic reactions, a diagnosis it termed “combat exhaustion.”

In 1952, though continuing to recognize combat as a cause of a broad range of disabling reactions to traumatic stress, the American Psychological Association’s (APA) first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), modified the War Department Technical Bulletin’s nomenclature, substituting ““Gross Stress Reaction” for the Combat Exhaustion diagnosis.To remedy this high rate of psychiatric injuries suffered by soldiers during World War II, and to maintain maximum warrior effectiveness, several treatment modifications and changes in deployment protocols were implemented following the war.

To fulfill President Lincoln’s Promise to care for those who have served in our nation’s military and for their families, caregivers, and survivors. —Mission statement of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The United States Government’s obligation to its veterans under the enlistment contract is to provide access to quality medical treatment including mental health services and disability compensation. Vice President Kamala Harris recently reasserted this obligation during a Veterans Day address at Arlington National Cemetery.

Since the founding of the United States, service members have defended the nation. In return, the nation has an obligation to take care of those same veterans.

Co-conspiring with the government to focus on the individual’s premilitary history, ignoring the effects the war experience may have had upon the veterans, the APA removed the diagnosis of Gross Stress Reaction from its revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders II in 1968

This obligation extends beyond the soldiers’ time in military service and entails providing ongoing support and resources to help veterans reintegrate into society, address any physical or mental health challenges, and ensure their overall well-being.

During the initial months of the Korean War, acute psychiatric casualties remained unacceptably high—250 per 1,000 men per year. As the treatment and deployment modifications noted above were eventually implemented in Korea and then in Vietnam, the numbers improved significantly. Tragically, however, these improving numbers—acute psychiatric casualties dropped to approximately 11.5 per 1,000 men per year during the Vietnam War—and the fact that the symptoms presented by returning Vietnam Veterans occurred some 9-30 months after demobilization, provided the impetus for the VA, the government agency charged with the care and treatment of veterans, to ignore or misdiagnose their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries claiming them to be nonservice connected, unrelated to the their experiences in Vietnam. Consequently, the government accepted no responsibility to treat or compensate the veterans for what they alleged to be preexisting conditions, profound though they may be.

Co-conspiring with the government to focus on the individual’s premilitary history, ignoring the effects the war experience may have had upon the veterans, the APA removed the diagnosis of Gross Stress Reaction from its revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders II in 1968, curiously the same year as the Tet Offensive. This tragic omission left the returning Vietnam Veterans without a codified psychiatric diagnosis with which to explain the causal relationship between their service in war and their psychological, emotional, and moral injuries.

The programming and conditioning Vietnam era recruits were subjected to in boot camp and basic training, later reinforced by the “ambiguities” posed by the guerilla warfare they experienced in Vietnam, diminished the soldiers’ moral being and encouraged brutality and eventually atrocity, causing them ultimately to view themselves not as noble warriors but as beasts and murderers. As the true nature of demythologized war became apparent, Vietnam veterans realized that they and the American people had been lied to, that their being in Vietnam had nothing to do with preserving the freedom either of Americans or of the Vietnamese, that the “enemy” they were killing and that were killing them were not terrorists or ideologues bent upon world domination as they had been told, but nationalists and freedom fighters struggling against yet another in a long series of colonialists, invaders, and occupiers. Saddled with fighting a war of attrition with weapons that were defective and unreliable, often resulting in their injury or death, the veterans felt betrayed while in Vietnam and abandoned upon their return home.

Understandably distrustful of government bureaucracy, disappointed with the failure of the government to end the war in Vietnam, dismayed with “establishment” psychiatric services, and frustrated with having their injuries ignored or misdiagnosed by the VA, Vietnam veterans saw no other recourse than to form a self-help group, an activist organization, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, intending to “get their heads together,” fend for themselves, and “structure their own solutions.”

In December 1970, VVAW members from their New York City headquarters began their peer support network, initially with no professional clinical involvement. Termed “rap groups,” these makeshift meetings were intended as a venue for VVAW members to share their war experiences; express grievances; work through the guilt, rage, depression, and alienation; and build community based upon their common experiences during the Vietnam War. As the rap groups progressed and trust increased, members shared honestly, felt less burdened, and became better able to connect with the outside world. Jan Barry, one of VVAW’s founders, after attending a lecture on the Hiroshima survivors by noted anti-war Harvard psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, invited Lifton to join the sessions, not as a leader or facilitator, but as a “resource” person and observer who could help the group focus and, hopefully, draw coherent conclusions about their experiences. In his letter of invitation, Barry succinctly described the veterans who would be participating in the rap groups and what they hoped to accomplish as an organization:

Guys are hurting. They’re opposed to the war, and they want to deal with their hurt, and they don’t want to go to the VA. They also want to make known to the world what war is like. Can you help us in some way? (Nicosia, 2001, p. 161)

Together with New York University psychiatrist Chaim Shatan, Lifton attended the rap sessions, the goals of which became (1) psychological transformation (healing), (2) publicizing the veteran’s destructive personal experiences to educate the public regarding the realities and the human cost of the war in Vietnam, (3) appealing to the consciences of the American public regarding the immorality of the war, (4) encouraging activism to alter the political policies that sustained the war, and finally (5) motivating government leaders to immediately end the war, bring all the soldiers home, and provide effective treatment for their physical, psychological, emotional, and moral injuries upon their return.

Lifton and Chatan quickly recognized that what they had become involved in was a new “nonhierarchical form of dialogic therapy” in which the issues and concerns they discussed were common to the war experience and did not fit any standard DSM diagnostic category. Through the courage, transparency, and persistence of the VVAW rap group participants and the professionalism, knowledge, efforts, and dedication of the VVAW psychiatrists who championed their cause, the characterization of returning veterans began to transition from the stigmatizing stereotypes of drug addicts, baby killers, ticking time bombs, and junkies to psychologically, emotionally, and morally injured—Post-Vietnam Syndrome.

In addition to establishing the symptomatology and etiology of what later became known as post-traumatic stress disorder, another important outcome of the rap group experience was the correlation between the two primary goals of VVAW, healing and bringing an end to the war. For healing to occur more than just discussion, the communalization of grief, was required. To heal, veterans must become engaged, in what I have termed elsewhere as “doing penance for the sacrilege of war.” That is, engaging in political and social activism to end the war and to right the wrongs they had committed—protest and demonstration—became inseparable and integral to the healing process.

To men who have been steeped in death and evil beyond imagination, a “talking cure” alone is worthless. And merely sharing their grief and outrage with comrades... is similarly unsatisfying. Active participation in the public arena, active opposition to the very war policies they helped carry out, was essential. (Shatan, The Grief of Soldiers, 1973)

Hence the importance of the integration of VVAW’s rap groups with their activism. Of healing—coming to grips with their experiences in war—with educating the public about war’s realities through protest and demonstration. Through guerilla theater, VVAW members, dressed in combat regalia, acted out the detainment and abuse of civilian spectators. During “Operation Dewey Canyon III,” arguably one of VVAW’s most successful actions, more than 1000 veterans, after saying their name, their units, and making a statement about the illegality of the war, threw their medals over the fence surrounding the Capitol building.

By throwing onto the steps of Congress the medals with which they were rewarded for murder in a war they had come to abhor, the veterans symbolically shed some of their guilt. In addition to their dramatic political impact, these demonstrations have profound therapeutic meaning. Instead of acting under orders, the vets originated action on their own behalf to regain control over events—over their lives—that were wrested from them in Vietnam. (Shatan, The Grief of Soldiers, 1973)

Despite the plethora of evidence to the contrary, many Americans continue to embrace, even until today, the mythology of the conflict in Vietnam as a just war against communist aggression. While quick to thank veterans for their “service” and alleging gratitude for their sacrifices, these self-proclaimed patriots have little understanding of the conditioning Vietnam era veterans endured during basic training and boot camp to increase their lethality—their ability to kill a dehumanized “enemy” in a guerilla and counterinsurgency war. Nor do they appreciate how the long-term effects of this training, reinforced by life amid the violence, death, horror, trauma, anxiety, and fatigue of war, eroded the warriors’ moral being, undid character, and reduced decent men and women to savages making the likelihood of atrocity inevitable. Most tragically, they were and in many cases remain indifferent to the devastating psychological, emotional, and moral injuries veterans suffered consequent to their experiences in the war.

Since, at its height, VVAW had an estimated 25,000 members, only a fraction of the 2.5 million veterans who served in Vietnam, these critics allege they received attention completely out of proportion to their numbers and their importance. Further, despite their sacrifices and all that they have and continue to accomplish, militarists and those who seek to continue to benefit from war have worked diligently to condemn members of VVAW and other veteran activist groups such as About Face:Veterans Against War, formally the Iraq Veterans Against the War, as traitors to this nation, to their fellow veterans, and to portray their work as misguided and as an existential threat to America’s survival. As a result, many in this nation fail to appreciate VVAW’s contribution and recognize the debt it owes its members.

While suffering the physical, psychological, emotional, and moral injuries sustained in the war, VVAW members displayed the courage and forthrightness to realize and “confess” to being instruments of this nation’s illegal and immoral war during its Winter Soldier Hearings. Through their testimony and truth-telling, those who would listen were educated about what war does to those who fight it and the crimes—the atrocities—that were committed in their names. Through their activism—guerilla theater, Dewey Canyon III, etc.—the public learned about what transpires in guerilla and counterinsurgency war. Through their efforts to effect healing—their unique and effective therapeutic “rap groups”—in which they involved and educated dedicated clinical professionals—Robert Jay Lifton, Chaim Shatan, among others—VVAW members were instrumental in bringing recognition and attention to trauma-related and moral injuries—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Combat Related Moral Injury. By so doing, a codified psychiatric diagnosis was again recognized and included in the revised edition of the DSM III with which to explain the symptomatology and etiology of the injuries suffered not only by soldiers in war but by first responders and victims of natural disasters, rapes, etc. Finally, through their activism and the attention they brought to the war, VVAW took the lead in influencing, orchestrating, and augmenting opposition to the American war in Vietnam that eventually contributed to bringing it to its ignominious conclusion.

So should you have the privilege one day to meet members of VVAW or other activist veterans, do take the time to thank them for their service, not for fighting some ill-conceived, immoral war, however, but for a lifetime of sacrifice and commitment to continuing their difficult and at most times thankless work for peace and social justice.