SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Concerned that Latin American countries have been growing close to China, the Trump administration has been using drugs as an excuse for a more aggressive US role in the region.

The Trump administration is escalating US drug wars in Latin America as a cover for imperialism.

While the administration directs a military buildup in the Caribbean, killing people who it claims are drug smugglers, it is preparing to intervene in Latin American countries for the purpose of opening their markets to US businesses. The administration’s priority is gaining access to Latin American resources, a main focus of its foreign policy, just as the highest-level officials have indicated.

“Increasingly, on geopolitical issue after geopolitical issue, it is access to raw material and industrial capacity that is at the core both of the decisions that we’re making and the areas that we’re prioritizing,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in June.

One of the major contributions of the United States to imperial history is drug war imperialism. Developed as part of the so-called “war on drugs,” which the Nixon administration began in the 1970s and the Reagan administration expanded in the 1980s, drug war imperialism has been one of the primary means by which the United States has intervened in Latin America.

During the late 1980s, the United States set the standard for drug war imperialism in Panama. After discrediting Manuel Noriega with drug charges, officials in Washington organized a military intervention to remove the Panamanian ruler from power.

Under the direction of the George H. W. Bush administration, the US military invaded Panama, captured Noriega, and brought him to the United States, where he was tried, convicted, and imprisoned on drug charges. US officials framed the operation as part of the war on drugs, but their primary concern was bringing to power a friendly government that acted on behalf of US interests. US officials valued Panama for its location and for the Panama Canal, a critical node for US trade.

Decades of US-backed military operations... have brought terrible violence to Latin America while failing to stop the flow of drugs to the United States.

In the following decades, the United States exercised other forms of drug war imperialism in Latin America. In 2000, the administration of Bill Clinton implemented Plan Colombia, a program of US military support for the Colombian government. US officials framed Plan Colombia as a counter-narcotics program, but their objective was to empower the Colombian military in its war against leftist revolutionaries, especially the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

In 2007, the administration of George W. Bush pushed forward a similar program in Mexico. With the Mérida Initiative, the Bush administration empowered the Mexican government to intensify its war against drug cartels. US officials saw the program as way to forge closer relations with the Mexican military and confront the country’s drug traffickers, who were making it difficult for US businesses to operate in the country.

Multiple administrations faced strong criticisms over the programs, especially as drug-related violence increased in Colombia and Mexico. A Colombian truth commission estimated that 450,000 people were killed in Colombia from 1985 to 2018, with 80% of the deaths being civilians. There have been hundreds of thousands of drug-related deaths in Mexico, with the numbers still increasing by tens of thousands every year.

Although most US officials insisted that criminal organizations in Latin America bore primary responsibility for drug-related violence, some began to question the US approach. They wondered whether US-backed drug wars were ignoring root causes of the drug problem, such as the US demand for drugs.

“As Americans we should be ashamed of ourselves that we have done almost nothing to get our arms around drug demand,” Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly said in 2017. “And we point fingers at people to the south and tell them they need to do more about drug production and drug trafficking.”

In recent years, some critics have even cast the drug wars as a failure. Decades of US-backed military operations, they have noted, have brought terrible violence to Latin America while failing to stop the flow of drugs to the United States.

“Drugs have kept flowing, and Americans and Latin Americans have kept dying,” Shannon O’Neil, who chaired a congressionally-mandated drug policy commission, told Congress in 2020. “Something is not working.”

Despite the recognition in Washington that drug wars do not counter drugs, the Trump administration is using them to create a justification for military operations across Latin America.

The Trump administration laid the groundwork for an intensified version of drug war imperialism shortly after entering office. On day one, Trump issued an executive order to designate drug cartels as terrorist organizations, claiming they “present an unusual and extraordinary threat” and declaring a national emergency to deal with them. The State Department quickly followed by labeling drug cartels and other criminal organizations as terrorist organizations.

In July, Trump secretly ordered the Pentagon to start attacking drug cartels.

“That’s the country we should be going to war with,” Trump is alleged to have said in 2017, during his first year in office. “They have all that oil and they’re right on our back door.”

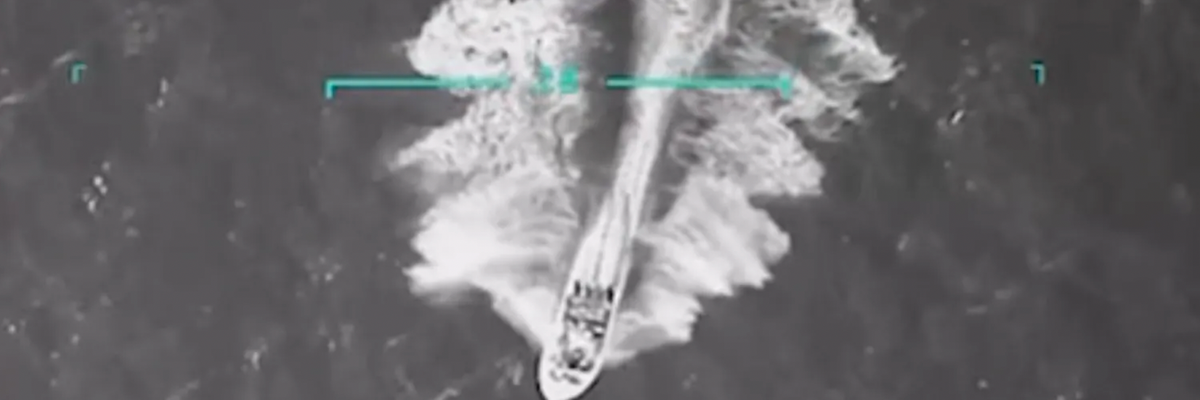

Earlier this month, the US military began to implement Trump’s orders by launching a drone strike on a speedboat in the Caribbean that was carrying 11 people. Administration officials accused the people on board of being Venezuelan drug smugglers, but critics questioned the Trump administration’s claims and argued that its actions were illegal. Some accused the Trump administration of murder.

Trump and Rubio discredited the administration’s justification for the attack by making different claims about the destination of the speedboat. Whereas Rubio said that it was headed toward Trinidad, Trump said that it was destined for the United States. Wanting to be consistent with the president, Rubio then changed his story, claiming that the speedboat was going to the United States.

Critics have also questioned whether the administration has been acting over concerns about drugs. One of their main points has been that Venezuela’s involvement in the drug trade has been overstated.

When Rubio faced questions about the administration’s attack on the speedboat, he dismissed reports that attributed less importance to Venezuela, including those by the United Nations.

“I don’t care what the UN says,” Rubio said.

Trump displayed the same disregard when he announced on social media on Monday that he ordered another strike on a boat in the Caribbean, saying that it killed 3 people. “BE WARNED,” he wrote. “WE ARE HUNTING YOU!”

For many years, in fact, several of the highest-level officials in the Trump administration have been eager for the United States to play a more aggressive role in Latin America not for the purpose of countering drugs but with the goal of acquiring greater access to the region’s resources.

It has long been known that Trump values Venezuela because it is home to the largest known oil reserves in the world.

“That’s the country we should be going to war with,” Trump is alleged to have said in 2017, during his first year in office. “They have all that oil and they’re right on our back door.”

Several high-level officials in the first Trump administration shared the president’s views. In 2018, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis commented that Venezuelan leaders “sit on enormous oil reserves.”

When the first Trump administration rallied Venezuelan opposition forces in 2019 in a failed attempt to overthrow the Venezuelan government, several high-level officials boasted about the potential riches of Venezuelan oil, suggesting that it would be a boon to US investors.

“It is a country with this incredible resource of petroleum, the greatest in the world,” then-Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams told Congress. “So I think you will find that with a change of leadership and a change of economic policy, that there will be lots of people who are ready to invest, and I think the World Bank and the IMF in particular will be ready to help start that engine.”

Since the start of his second administration, Trump has continued to think about the country’s oil, even as he has brought different people into his administration.

“You’re going to have one guy sitting there with a lot of oil under his feet,” Trump said in February, referring to Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. “That’s not a good situation.”

While the Trump administration has forged ahead with its expansion of US military operations in the Caribbean, giving special attention to Venezuela, it has deployed a familiar argument. Just as past administrations have done, the Trump administration has claimed that it is going to war against drugs.

“On day one of the Trump administration, we declared an all-out war on the dealers, smugglers, traffickers, and cartels,” Trump said in July, referring to his executive order to target drug cartels as terrorist organizations.

Administration officials have supported the president’s approach. Leading the way, Rubio has repeatedly insisted on the need to take military action against drug traffickers.

What the Trump administration is doing in short, is going to war against drugs as a cover for opening Latin American markets to US businesses.

“The president of the United States is going to wage war on narcoterrorist organizations,” Rubio said earlier this month.

Still, US officials have gestured at ulterior motives. When Rubio has spoken about the administration’s drug wars, he has indicated that he is focused on creating conditions in Latin America that will enable US businesses to operate there more effectively.

“It’s nearly impossible to attract foreign investment into a country unless you have security,” Rubio said during a recent visit to Ecuador, where he acknowledged ongoing negotiations over a trade deal and a military base.

In fact, the Trump administration has made it clear that it is focused on creating new opportunities for US businesses and investors in Latin America. Concerned that Latin American countries have been growing close to China, the Trump administration has been using drugs as an excuse for a more aggressive US role in the region.

What the Trump administration is doing in short, is going to war against drugs as a cover for opening Latin American markets to US businesses. Turning to a familiar playbook, it is implementing drug war imperialism.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The Trump administration is escalating US drug wars in Latin America as a cover for imperialism.

While the administration directs a military buildup in the Caribbean, killing people who it claims are drug smugglers, it is preparing to intervene in Latin American countries for the purpose of opening their markets to US businesses. The administration’s priority is gaining access to Latin American resources, a main focus of its foreign policy, just as the highest-level officials have indicated.

“Increasingly, on geopolitical issue after geopolitical issue, it is access to raw material and industrial capacity that is at the core both of the decisions that we’re making and the areas that we’re prioritizing,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in June.

One of the major contributions of the United States to imperial history is drug war imperialism. Developed as part of the so-called “war on drugs,” which the Nixon administration began in the 1970s and the Reagan administration expanded in the 1980s, drug war imperialism has been one of the primary means by which the United States has intervened in Latin America.

During the late 1980s, the United States set the standard for drug war imperialism in Panama. After discrediting Manuel Noriega with drug charges, officials in Washington organized a military intervention to remove the Panamanian ruler from power.

Under the direction of the George H. W. Bush administration, the US military invaded Panama, captured Noriega, and brought him to the United States, where he was tried, convicted, and imprisoned on drug charges. US officials framed the operation as part of the war on drugs, but their primary concern was bringing to power a friendly government that acted on behalf of US interests. US officials valued Panama for its location and for the Panama Canal, a critical node for US trade.

Decades of US-backed military operations... have brought terrible violence to Latin America while failing to stop the flow of drugs to the United States.

In the following decades, the United States exercised other forms of drug war imperialism in Latin America. In 2000, the administration of Bill Clinton implemented Plan Colombia, a program of US military support for the Colombian government. US officials framed Plan Colombia as a counter-narcotics program, but their objective was to empower the Colombian military in its war against leftist revolutionaries, especially the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

In 2007, the administration of George W. Bush pushed forward a similar program in Mexico. With the Mérida Initiative, the Bush administration empowered the Mexican government to intensify its war against drug cartels. US officials saw the program as way to forge closer relations with the Mexican military and confront the country’s drug traffickers, who were making it difficult for US businesses to operate in the country.

Multiple administrations faced strong criticisms over the programs, especially as drug-related violence increased in Colombia and Mexico. A Colombian truth commission estimated that 450,000 people were killed in Colombia from 1985 to 2018, with 80% of the deaths being civilians. There have been hundreds of thousands of drug-related deaths in Mexico, with the numbers still increasing by tens of thousands every year.

Although most US officials insisted that criminal organizations in Latin America bore primary responsibility for drug-related violence, some began to question the US approach. They wondered whether US-backed drug wars were ignoring root causes of the drug problem, such as the US demand for drugs.

“As Americans we should be ashamed of ourselves that we have done almost nothing to get our arms around drug demand,” Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly said in 2017. “And we point fingers at people to the south and tell them they need to do more about drug production and drug trafficking.”

In recent years, some critics have even cast the drug wars as a failure. Decades of US-backed military operations, they have noted, have brought terrible violence to Latin America while failing to stop the flow of drugs to the United States.

“Drugs have kept flowing, and Americans and Latin Americans have kept dying,” Shannon O’Neil, who chaired a congressionally-mandated drug policy commission, told Congress in 2020. “Something is not working.”

Despite the recognition in Washington that drug wars do not counter drugs, the Trump administration is using them to create a justification for military operations across Latin America.

The Trump administration laid the groundwork for an intensified version of drug war imperialism shortly after entering office. On day one, Trump issued an executive order to designate drug cartels as terrorist organizations, claiming they “present an unusual and extraordinary threat” and declaring a national emergency to deal with them. The State Department quickly followed by labeling drug cartels and other criminal organizations as terrorist organizations.

In July, Trump secretly ordered the Pentagon to start attacking drug cartels.

“That’s the country we should be going to war with,” Trump is alleged to have said in 2017, during his first year in office. “They have all that oil and they’re right on our back door.”

Earlier this month, the US military began to implement Trump’s orders by launching a drone strike on a speedboat in the Caribbean that was carrying 11 people. Administration officials accused the people on board of being Venezuelan drug smugglers, but critics questioned the Trump administration’s claims and argued that its actions were illegal. Some accused the Trump administration of murder.

Trump and Rubio discredited the administration’s justification for the attack by making different claims about the destination of the speedboat. Whereas Rubio said that it was headed toward Trinidad, Trump said that it was destined for the United States. Wanting to be consistent with the president, Rubio then changed his story, claiming that the speedboat was going to the United States.

Critics have also questioned whether the administration has been acting over concerns about drugs. One of their main points has been that Venezuela’s involvement in the drug trade has been overstated.

When Rubio faced questions about the administration’s attack on the speedboat, he dismissed reports that attributed less importance to Venezuela, including those by the United Nations.

“I don’t care what the UN says,” Rubio said.

Trump displayed the same disregard when he announced on social media on Monday that he ordered another strike on a boat in the Caribbean, saying that it killed 3 people. “BE WARNED,” he wrote. “WE ARE HUNTING YOU!”

For many years, in fact, several of the highest-level officials in the Trump administration have been eager for the United States to play a more aggressive role in Latin America not for the purpose of countering drugs but with the goal of acquiring greater access to the region’s resources.

It has long been known that Trump values Venezuela because it is home to the largest known oil reserves in the world.

“That’s the country we should be going to war with,” Trump is alleged to have said in 2017, during his first year in office. “They have all that oil and they’re right on our back door.”

Several high-level officials in the first Trump administration shared the president’s views. In 2018, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis commented that Venezuelan leaders “sit on enormous oil reserves.”

When the first Trump administration rallied Venezuelan opposition forces in 2019 in a failed attempt to overthrow the Venezuelan government, several high-level officials boasted about the potential riches of Venezuelan oil, suggesting that it would be a boon to US investors.

“It is a country with this incredible resource of petroleum, the greatest in the world,” then-Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams told Congress. “So I think you will find that with a change of leadership and a change of economic policy, that there will be lots of people who are ready to invest, and I think the World Bank and the IMF in particular will be ready to help start that engine.”

Since the start of his second administration, Trump has continued to think about the country’s oil, even as he has brought different people into his administration.

“You’re going to have one guy sitting there with a lot of oil under his feet,” Trump said in February, referring to Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. “That’s not a good situation.”

While the Trump administration has forged ahead with its expansion of US military operations in the Caribbean, giving special attention to Venezuela, it has deployed a familiar argument. Just as past administrations have done, the Trump administration has claimed that it is going to war against drugs.

“On day one of the Trump administration, we declared an all-out war on the dealers, smugglers, traffickers, and cartels,” Trump said in July, referring to his executive order to target drug cartels as terrorist organizations.

Administration officials have supported the president’s approach. Leading the way, Rubio has repeatedly insisted on the need to take military action against drug traffickers.

What the Trump administration is doing in short, is going to war against drugs as a cover for opening Latin American markets to US businesses.

“The president of the United States is going to wage war on narcoterrorist organizations,” Rubio said earlier this month.

Still, US officials have gestured at ulterior motives. When Rubio has spoken about the administration’s drug wars, he has indicated that he is focused on creating conditions in Latin America that will enable US businesses to operate there more effectively.

“It’s nearly impossible to attract foreign investment into a country unless you have security,” Rubio said during a recent visit to Ecuador, where he acknowledged ongoing negotiations over a trade deal and a military base.

In fact, the Trump administration has made it clear that it is focused on creating new opportunities for US businesses and investors in Latin America. Concerned that Latin American countries have been growing close to China, the Trump administration has been using drugs as an excuse for a more aggressive US role in the region.

What the Trump administration is doing in short, is going to war against drugs as a cover for opening Latin American markets to US businesses. Turning to a familiar playbook, it is implementing drug war imperialism.

The Trump administration is escalating US drug wars in Latin America as a cover for imperialism.

While the administration directs a military buildup in the Caribbean, killing people who it claims are drug smugglers, it is preparing to intervene in Latin American countries for the purpose of opening their markets to US businesses. The administration’s priority is gaining access to Latin American resources, a main focus of its foreign policy, just as the highest-level officials have indicated.

“Increasingly, on geopolitical issue after geopolitical issue, it is access to raw material and industrial capacity that is at the core both of the decisions that we’re making and the areas that we’re prioritizing,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in June.

One of the major contributions of the United States to imperial history is drug war imperialism. Developed as part of the so-called “war on drugs,” which the Nixon administration began in the 1970s and the Reagan administration expanded in the 1980s, drug war imperialism has been one of the primary means by which the United States has intervened in Latin America.

During the late 1980s, the United States set the standard for drug war imperialism in Panama. After discrediting Manuel Noriega with drug charges, officials in Washington organized a military intervention to remove the Panamanian ruler from power.

Under the direction of the George H. W. Bush administration, the US military invaded Panama, captured Noriega, and brought him to the United States, where he was tried, convicted, and imprisoned on drug charges. US officials framed the operation as part of the war on drugs, but their primary concern was bringing to power a friendly government that acted on behalf of US interests. US officials valued Panama for its location and for the Panama Canal, a critical node for US trade.

Decades of US-backed military operations... have brought terrible violence to Latin America while failing to stop the flow of drugs to the United States.

In the following decades, the United States exercised other forms of drug war imperialism in Latin America. In 2000, the administration of Bill Clinton implemented Plan Colombia, a program of US military support for the Colombian government. US officials framed Plan Colombia as a counter-narcotics program, but their objective was to empower the Colombian military in its war against leftist revolutionaries, especially the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

In 2007, the administration of George W. Bush pushed forward a similar program in Mexico. With the Mérida Initiative, the Bush administration empowered the Mexican government to intensify its war against drug cartels. US officials saw the program as way to forge closer relations with the Mexican military and confront the country’s drug traffickers, who were making it difficult for US businesses to operate in the country.

Multiple administrations faced strong criticisms over the programs, especially as drug-related violence increased in Colombia and Mexico. A Colombian truth commission estimated that 450,000 people were killed in Colombia from 1985 to 2018, with 80% of the deaths being civilians. There have been hundreds of thousands of drug-related deaths in Mexico, with the numbers still increasing by tens of thousands every year.

Although most US officials insisted that criminal organizations in Latin America bore primary responsibility for drug-related violence, some began to question the US approach. They wondered whether US-backed drug wars were ignoring root causes of the drug problem, such as the US demand for drugs.

“As Americans we should be ashamed of ourselves that we have done almost nothing to get our arms around drug demand,” Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly said in 2017. “And we point fingers at people to the south and tell them they need to do more about drug production and drug trafficking.”

In recent years, some critics have even cast the drug wars as a failure. Decades of US-backed military operations, they have noted, have brought terrible violence to Latin America while failing to stop the flow of drugs to the United States.

“Drugs have kept flowing, and Americans and Latin Americans have kept dying,” Shannon O’Neil, who chaired a congressionally-mandated drug policy commission, told Congress in 2020. “Something is not working.”

Despite the recognition in Washington that drug wars do not counter drugs, the Trump administration is using them to create a justification for military operations across Latin America.

The Trump administration laid the groundwork for an intensified version of drug war imperialism shortly after entering office. On day one, Trump issued an executive order to designate drug cartels as terrorist organizations, claiming they “present an unusual and extraordinary threat” and declaring a national emergency to deal with them. The State Department quickly followed by labeling drug cartels and other criminal organizations as terrorist organizations.

In July, Trump secretly ordered the Pentagon to start attacking drug cartels.

“That’s the country we should be going to war with,” Trump is alleged to have said in 2017, during his first year in office. “They have all that oil and they’re right on our back door.”

Earlier this month, the US military began to implement Trump’s orders by launching a drone strike on a speedboat in the Caribbean that was carrying 11 people. Administration officials accused the people on board of being Venezuelan drug smugglers, but critics questioned the Trump administration’s claims and argued that its actions were illegal. Some accused the Trump administration of murder.

Trump and Rubio discredited the administration’s justification for the attack by making different claims about the destination of the speedboat. Whereas Rubio said that it was headed toward Trinidad, Trump said that it was destined for the United States. Wanting to be consistent with the president, Rubio then changed his story, claiming that the speedboat was going to the United States.

Critics have also questioned whether the administration has been acting over concerns about drugs. One of their main points has been that Venezuela’s involvement in the drug trade has been overstated.

When Rubio faced questions about the administration’s attack on the speedboat, he dismissed reports that attributed less importance to Venezuela, including those by the United Nations.

“I don’t care what the UN says,” Rubio said.

Trump displayed the same disregard when he announced on social media on Monday that he ordered another strike on a boat in the Caribbean, saying that it killed 3 people. “BE WARNED,” he wrote. “WE ARE HUNTING YOU!”

For many years, in fact, several of the highest-level officials in the Trump administration have been eager for the United States to play a more aggressive role in Latin America not for the purpose of countering drugs but with the goal of acquiring greater access to the region’s resources.

It has long been known that Trump values Venezuela because it is home to the largest known oil reserves in the world.

“That’s the country we should be going to war with,” Trump is alleged to have said in 2017, during his first year in office. “They have all that oil and they’re right on our back door.”

Several high-level officials in the first Trump administration shared the president’s views. In 2018, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis commented that Venezuelan leaders “sit on enormous oil reserves.”

When the first Trump administration rallied Venezuelan opposition forces in 2019 in a failed attempt to overthrow the Venezuelan government, several high-level officials boasted about the potential riches of Venezuelan oil, suggesting that it would be a boon to US investors.

“It is a country with this incredible resource of petroleum, the greatest in the world,” then-Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams told Congress. “So I think you will find that with a change of leadership and a change of economic policy, that there will be lots of people who are ready to invest, and I think the World Bank and the IMF in particular will be ready to help start that engine.”

Since the start of his second administration, Trump has continued to think about the country’s oil, even as he has brought different people into his administration.

“You’re going to have one guy sitting there with a lot of oil under his feet,” Trump said in February, referring to Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. “That’s not a good situation.”

While the Trump administration has forged ahead with its expansion of US military operations in the Caribbean, giving special attention to Venezuela, it has deployed a familiar argument. Just as past administrations have done, the Trump administration has claimed that it is going to war against drugs.

“On day one of the Trump administration, we declared an all-out war on the dealers, smugglers, traffickers, and cartels,” Trump said in July, referring to his executive order to target drug cartels as terrorist organizations.

Administration officials have supported the president’s approach. Leading the way, Rubio has repeatedly insisted on the need to take military action against drug traffickers.

What the Trump administration is doing in short, is going to war against drugs as a cover for opening Latin American markets to US businesses.

“The president of the United States is going to wage war on narcoterrorist organizations,” Rubio said earlier this month.

Still, US officials have gestured at ulterior motives. When Rubio has spoken about the administration’s drug wars, he has indicated that he is focused on creating conditions in Latin America that will enable US businesses to operate there more effectively.

“It’s nearly impossible to attract foreign investment into a country unless you have security,” Rubio said during a recent visit to Ecuador, where he acknowledged ongoing negotiations over a trade deal and a military base.

In fact, the Trump administration has made it clear that it is focused on creating new opportunities for US businesses and investors in Latin America. Concerned that Latin American countries have been growing close to China, the Trump administration has been using drugs as an excuse for a more aggressive US role in the region.

What the Trump administration is doing in short, is going to war against drugs as a cover for opening Latin American markets to US businesses. Turning to a familiar playbook, it is implementing drug war imperialism.