The gap between CEO compensation and median worker pay at Starbucks hit 6,666 to 1 last year. In other words, to make as much money as their CEO made last year, typical baristas would’ve had to start brewing macchiatos around the time humans first invented the wheel.

Starbucks takes the prize for the most obscene corporate pay disparities of 2024. But jaw-dropping gaps are the norm among America’s leading low-wage corporations.

This year’s edition of the annual Institute for Policy Studies Executive Excess report finds that CEOs of the 100 S&P 500 firms with the lowest median wages, a group we’ve dubbed the “Low-Wage 100,” have enjoyed skyrocketing pay over the past six years.

The Low-Wage 100

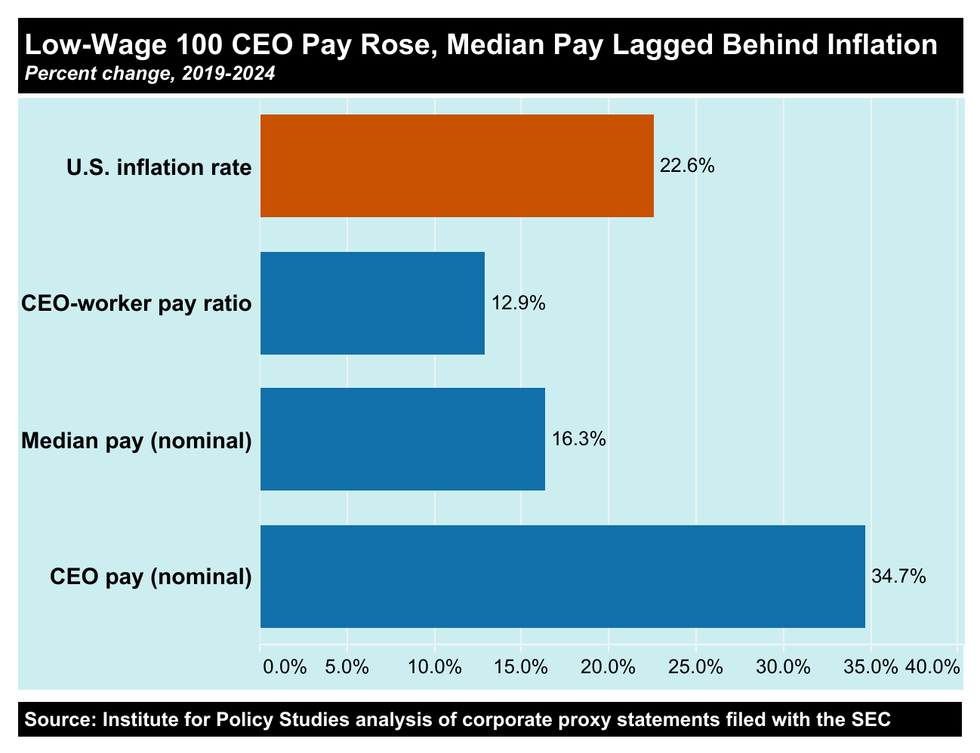

In 2024, average compensation for Low-Wage 100 top executives rose to $17.2 million, up 34.7% since 2019 (not adjusted for inflation). Global median worker pay at these firms stood at just $35,570, after increasing at a nominal rate of only 16.3% since 2019—significantly below the 22.6% US inflation rate. The Low-Wage 100 pay ratio increased 12.9% to 632 to 1 over the past half decade.

Buybacks Bonanza

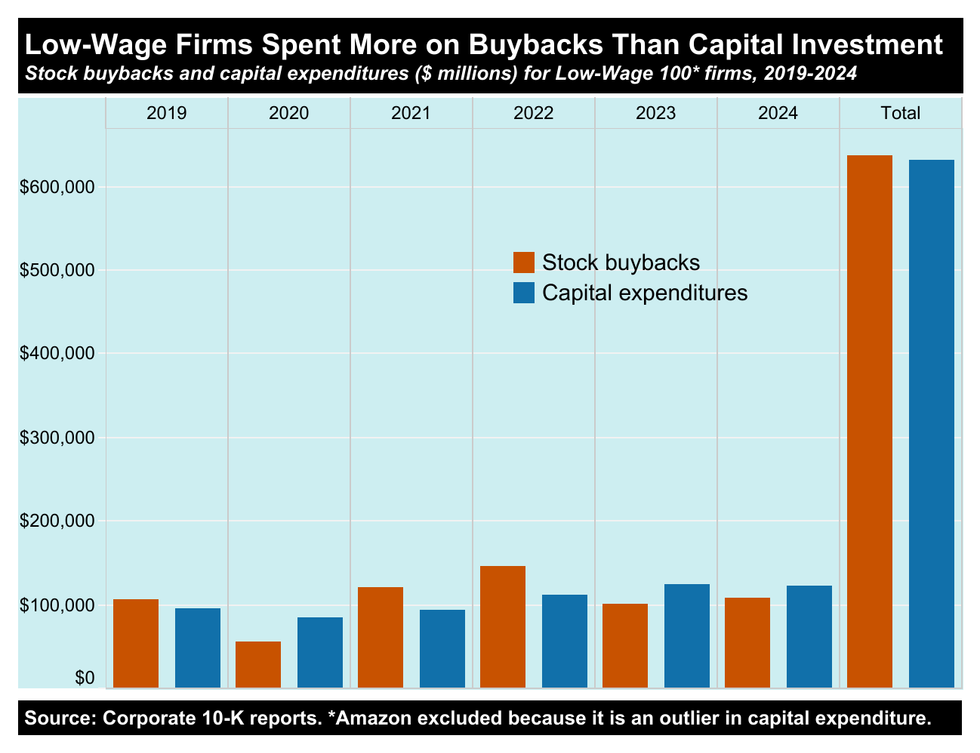

Here’s yet another sign of the Low-Wage 100’s skewed priorities: Between 2019 and 2024 these firms spent a combined $644 billion on stock buybacks. This once-illegal financial maneuver artificially inflates the value of a company’s shares and, in the process, pumps up the value of CEOs’ stock-based compensation. Even the most inept executives can rake in vast fortunes through this scam.

Every dollar spent on buybacks represents a dollar not spent on workers. The tradeoffs can be downright staggering. At Lowe’s, for instance, every one of their 273,000 employees could’ve gotten an annual $28,456 bonus over the past six years with the money the retailer blew on stock buybacks. Lowe’s median worker pay in 2024: $30,606.

80% of workers said they view corporate CEOs as overpaid, and nearly 70% said they do not believe their own company’s CEO could do the job they do for even one week.

If McDonald’s had spent their buyback outlays on worker bonuses during this period, they could’ve given all their employees an extra $18,338 per year—more than that company’s median wage.

Siphoning resources from workers to make CEOs even richer is especially outrageous at a time when so many Americans are struggling with high costs for groceries, housing, and other essentials.

Stock buybacks also divert resources from capital investments vital to long-term growth, such as employee training or upgrading technology, equipment, and properties.

At 56 Low-Wage 100 companies, outlays for stock buybacks actually exceeded capital expenditures between 2019 and 2024. If we exclude Amazon, a CapEx outlier, the Low-Wage 100 as a whole spent considerably more on buybacks than on capital expenditures over this six-year period.

Extensive research has also shown that excessive CEO compensation is bad for business because extreme internal pay disparities undermine employee morale and boost turnover rates.

Solutions to Executive Excess

As poll after poll after poll has shown, Americans across the political spectrum are fed up with overpaid CEOs and want government action. In one rather amusing recent survey, 80% of workers said they view corporate CEOs as overpaid, and nearly 70% said they do not believe their own company’s CEO could do the job they do for even one week.

How could policymakers incentivize more equitable pay practices? Several bills in the US Congress and state legislatures would increase taxes on corporations with huge CEO-worker pay gaps. Polls suggest this would be enormously popular. In one survey of likely voters, 89% of Democrats, 77% of Independents, and 71% of Republicans said they’d like to see tax hikes on companies that pay their CEOs more than 50 times what they pay their median employees.

Congress could also increase the 1% excise tax on stock buybacks that went into effect in 2023. If that tax had been set at 4%, the Low-Wage 100 would have owed approximately $6.3 billion in additional federal taxes on their share repurchases during the past two years. That revenue would’ve been enough to cover the cost of 327,218 public housing units for two years.

Policymakers have ample tools for tackling the problem of runaway CEO pay. Now they just need to listen to their constituents and get the job done.