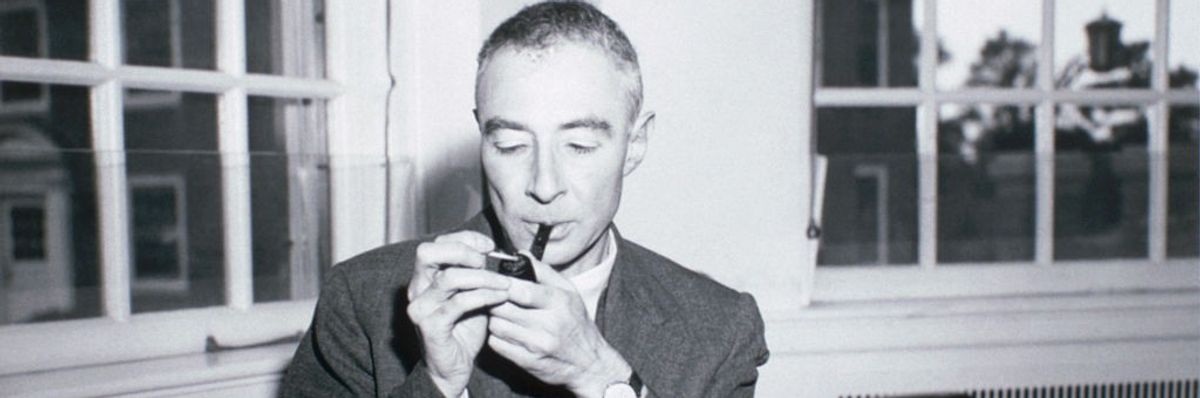

A mere 55 years after his death, the U.S. government has restored J. Robert Oppenheimer’s security clearance, which the Atomic Energy Commission had taken away from him in 1954, declaring him to be not simply a communist but, in all likelihood, a Soviet spy.

Oppenheimer, of course, is the father of the atomic bomb. He led the Manhattan Project during World War II, which birthed Little Boy and Fat Man, the bombs we dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, killing several hundred thousand people and ending the war. What happened next, however, was the Cold War, and suddenly commies—our former allies—were the personification of evil, and they were everywhere. The American government, in its infinite wisdom, knew it had no choice but to continue its nuclear weapons program and, for the sake of peace, put the world on the brink of Armageddon.

Hello, H-bomb!

War, the building block of the world’s governmental entities for uncounted millennia, had evolved to the brink of human extinction. Official government policy amounted to this:

So what?

“A key element in the case against Oppenheimer,” the

Times reported, “was derived from his resistance to early work on the hydrogen bomb, which could explode with 1,000 times the force of an atomic bomb.”

Oppenheimer challenged this official policy and shattered his career. Indeed, he saw immediately, as the newly developed bomb was tested at Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, that Planet Earth was in danger. A team of physicists had just exposed its ultimate vulnerability and he famously noted, as he witnessed the mushroom cloud, that words of Hindu scripture from the

Bhagavad-Gita entered his mind: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

He had not opposed dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as some of the Manhattan Project scientists, such as Leo Szilard, did, but when the war ended he became deeply committed to eliminating all possibility of future wars. One of the first actions he took, a week after the bombings, was to

write a letter to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, urging him to embrace common sense regarding further development of nuclear weapons.

“We believe,” he wrote, “that the safety of this nation—as opposed to its ability to inflict damage on an enemy power—cannot lie wholly or even primarily in its scientific or technical prowess. It can be based only on making future wars impossible. It is our unanimous and urgent recommendation to you that, despite the present incomplete exploitation of technical possibilities in this field, all steps be taken, all necessary international arrangements be made, to this one end.”

Making future wars impossible! What if American political forces had sufficient sanity to listen to Oppenheimer? Several months after writing this letter, he paid a visit to

President Harry Truman, attempting to discuss the placement of international control over further nuclear development. The president would have none of that. He kicked Oppenheimer out of the Oval Office.

Oppenheimer maintained his commitment to the transcendence of war, working with the Atomic Energy Commission to control the use of nuclear weapons—and standing firm in his opposition to the creation of the hydrogen bomb. He continued his opposition even as the bomb’s development progressed and nuclear tests began spreading fallout over “expendable” parts of the world. But, uh oh. Along came the McCarthy era and the accompanying Red Scare.

And in 1954, after 19 days of secret hearings, the Atomic Energy Commission revoked Oppenheimer’s security clearance. As

The New York Times noted, this “brought his career to a humiliating end. Until then a hero of American science, he lived out his life a broken man.” He died at age 62 in 1967.

“A key element in the case against Oppenheimer,” the

Times reported, “was derived from his resistance to early work on the hydrogen bomb, which could explode with 1,000 times the force of an atomic bomb. The physicist Edward Teller had long advocated a crash program to devise such a weapon, and told the 1954 hearing that he mistrusted Oppenheimer’s judgment. ‘I would feel personally more secure,’ he testified, ‘if public matters would rest in other hands.’”

But of course the “black mark of shame” that remained stuck to Oppenheimer for the rest of his life was that he was a commie, and maybe a spy—in other words, totally anti-American. This was the basic lie used against those who challenged the tenets of the Cold War. The commission’s secret hearings remained classified for 60 years. After they were declassified in 2014, historians expressed amazement that they contained virtually no damning evidence of any sort against Oppenheimer, and lots of testimony sympathetic to him. The revelations here seem primarily to expose the government’s interest in covering its own lies.

It was this past December that Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, chairman of the department that the Atomic Energy Commission had morphed into, nullified the revocation of Oppenheimer’s security clearance, declaring the 1954 hearing a “flawed process.” Getting the government to undo its wrong was a long,

arduous process, embarked on by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, the authors of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. It took them about 16 years. They finally succeeded in clearing his name.

And while I applaud their enormous effort and its result, I also note it isn’t finished yet. This is more than simply a personal matter: the righting of a bureaucratic wrong done to one man. The future of humanity remains at stake. The U.S. government has spent multi-trillions of dollars on

nuclear weapons development over the years, conducted a thousand-plus nuclear tests, and is currently in possession of 5,244 nuclear warheads, out of an insane global total of some 12,500. Perhaps it’s time to start listening to—and hearing—Oppenheimer’s words.