SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

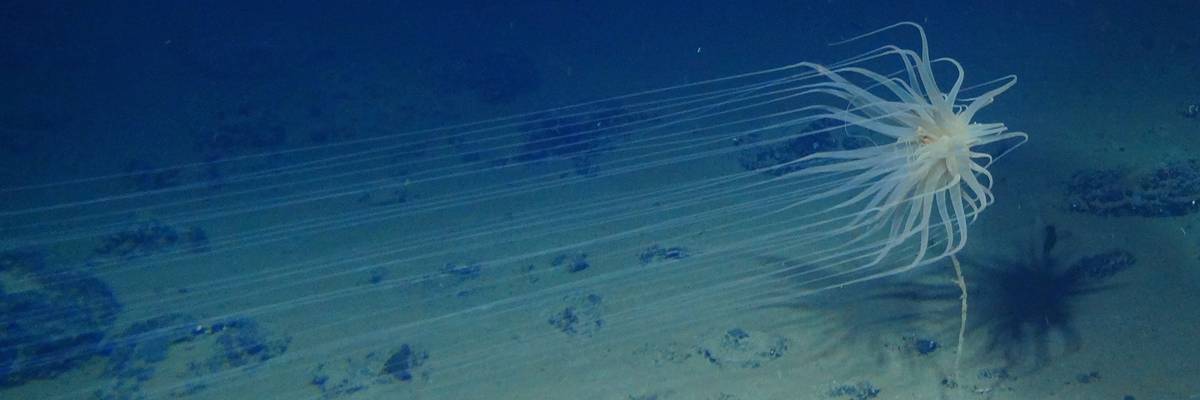

Relicanthus sp., a new species from a new order of Cnidaria, was collected at 4,100 meters in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ), an area that has been threatened with deep-sea mining.

A U.S. moratorium would send a strong message that it supports neither destructive seabed mining nor creating a new domestic market for minerals sourced from the ocean.

Five thousand new species were discovered earlier this year on a single research expedition to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone—a 1.7 million square mile area between Hawaii and Mexico. A steady stream of studies like this one reveal that from the darkest depths to the shallows by our shores, there are a multitude of undiscovered species in our oceans.

But the Clarion-Clipperton Zone also possesses a high concentration of minerals, and has therefore captured the eye of a risky new industry: deep-sea mining. If zones like this one are opened up for full-scale industrial mining, numerous newly discovered and undiscovered species will be at risk. Mining threatens to permanently destroy vast sea floors, undersea mountains, and otherworldly hydrothermal vents.

We urge U.S. President Joe Biden and his administration to call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, and stop this destructive industry from wreaking havoc on our seas. Right now, mining the deep seas is largely illegal under international laws, which means we can still prevent the destruction of untouched ocean areas and the multitudes they contain.

In short, deep-sea mining is an unnecessary threat to our global climate, the stability of our oceans, and the economy that depends on them.

But time is running out. At the end of July, nations will come together in Kingston, Jamaica at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which oversees commercial seabed mining in international waters, to advance draft mining rules. While the U.S. is not a member of the ISA, a U.S. moratorium would send a strong message that it supports neither destructive seabed mining nor creating a new domestic market for minerals sourced from the ocean. Twenty-five member states of the ISA—along with an increasing number of environmental, scientific, and Indigenous groups—already support a moratorium.

Yet the ISA is on track to allow deep-sea mining to begin–with increasingly lax regulation. In a recent draft of the ISA’s Mining Code, environmental protections for sensitive ecosystems had been stripped out. And in a breach of transparency norms, the identities of those proposing language to accelerate the approval of commercial mining licenses were omitted.

Some in the U.S. Congress are encouraging the acceleration of industrial deep-sea mining in U.S. federal waters, and federal agencies are preparing for the possibility of mining applications in the country, including an area off the Southeast U.S. called the Blake Plateau. This region, still scarred from test mining in the 1970s, is home to one of the world’s largest deep-sea coral reefs. Fishermen have long sought to protect this area, but deep-sea mining could put that protection—and their livelihoods—at risk. Last year, fishing industry groups joined the chorus of opposition to deep-sea mining.

The harm caused by deep-sea mining isn’t restricted to the sea floor. It will impact the entire water column top to bottom, and everyone and everything relying on it. Byproducts from mining could expose economically and culturally important species such as tunas to toxic sediment plumes, potentially contaminating fisheries. These plumes risk damaging known and unknown species at every depth, including those that sequester and transfer massive amounts of carbon.

Pro-mining interests argue that deep-sea minerals are needed for green energy technologies, like batteries for electric vehicles and solar panels, to meet future demand and mitigate climate change. We must not give in to this false choice between oceans and climate, and instead recognize that protecting our ocean is an equally important piece of keeping our planet habitable.

The ocean plays a critical role in global climate stability. Ocean creatures are vital strands in a delicate web of life that touches all of us. They are critical to coastal communities and economies, a potential source of game-changing medicines, and each plays a part in natural processes that help to regulate our climate.

Undermining ocean health to pursue potential mineral deposits is simply unnecessary. Demand for seabed minerals like nickel, copper, and cobalt is expected to level off or decline as clean energy technologies evolve and recycling capabilities improve. For example, batteries without seabed minerals now make up 36% of the electric vehicle market, and this is expected to increase to 60% by 2030.

In short, deep-sea mining is an unnecessary threat to our global climate, the stability of our oceans, and the economy that depends on them.

President Biden’s administration must make it clear that U.S. waters are not open for this destructive business. As nations gather to discuss the future of the industry, the Biden administration should join 25 other countries, including Canada and Mexico, in support of a global moratorium on deep-sea mining. For the sake of our ocean—and for all life on Earth that depends on it.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Five thousand new species were discovered earlier this year on a single research expedition to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone—a 1.7 million square mile area between Hawaii and Mexico. A steady stream of studies like this one reveal that from the darkest depths to the shallows by our shores, there are a multitude of undiscovered species in our oceans.

But the Clarion-Clipperton Zone also possesses a high concentration of minerals, and has therefore captured the eye of a risky new industry: deep-sea mining. If zones like this one are opened up for full-scale industrial mining, numerous newly discovered and undiscovered species will be at risk. Mining threatens to permanently destroy vast sea floors, undersea mountains, and otherworldly hydrothermal vents.

We urge U.S. President Joe Biden and his administration to call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, and stop this destructive industry from wreaking havoc on our seas. Right now, mining the deep seas is largely illegal under international laws, which means we can still prevent the destruction of untouched ocean areas and the multitudes they contain.

In short, deep-sea mining is an unnecessary threat to our global climate, the stability of our oceans, and the economy that depends on them.

But time is running out. At the end of July, nations will come together in Kingston, Jamaica at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which oversees commercial seabed mining in international waters, to advance draft mining rules. While the U.S. is not a member of the ISA, a U.S. moratorium would send a strong message that it supports neither destructive seabed mining nor creating a new domestic market for minerals sourced from the ocean. Twenty-five member states of the ISA—along with an increasing number of environmental, scientific, and Indigenous groups—already support a moratorium.

Yet the ISA is on track to allow deep-sea mining to begin–with increasingly lax regulation. In a recent draft of the ISA’s Mining Code, environmental protections for sensitive ecosystems had been stripped out. And in a breach of transparency norms, the identities of those proposing language to accelerate the approval of commercial mining licenses were omitted.

Some in the U.S. Congress are encouraging the acceleration of industrial deep-sea mining in U.S. federal waters, and federal agencies are preparing for the possibility of mining applications in the country, including an area off the Southeast U.S. called the Blake Plateau. This region, still scarred from test mining in the 1970s, is home to one of the world’s largest deep-sea coral reefs. Fishermen have long sought to protect this area, but deep-sea mining could put that protection—and their livelihoods—at risk. Last year, fishing industry groups joined the chorus of opposition to deep-sea mining.

The harm caused by deep-sea mining isn’t restricted to the sea floor. It will impact the entire water column top to bottom, and everyone and everything relying on it. Byproducts from mining could expose economically and culturally important species such as tunas to toxic sediment plumes, potentially contaminating fisheries. These plumes risk damaging known and unknown species at every depth, including those that sequester and transfer massive amounts of carbon.

Pro-mining interests argue that deep-sea minerals are needed for green energy technologies, like batteries for electric vehicles and solar panels, to meet future demand and mitigate climate change. We must not give in to this false choice between oceans and climate, and instead recognize that protecting our ocean is an equally important piece of keeping our planet habitable.

The ocean plays a critical role in global climate stability. Ocean creatures are vital strands in a delicate web of life that touches all of us. They are critical to coastal communities and economies, a potential source of game-changing medicines, and each plays a part in natural processes that help to regulate our climate.

Undermining ocean health to pursue potential mineral deposits is simply unnecessary. Demand for seabed minerals like nickel, copper, and cobalt is expected to level off or decline as clean energy technologies evolve and recycling capabilities improve. For example, batteries without seabed minerals now make up 36% of the electric vehicle market, and this is expected to increase to 60% by 2030.

In short, deep-sea mining is an unnecessary threat to our global climate, the stability of our oceans, and the economy that depends on them.

President Biden’s administration must make it clear that U.S. waters are not open for this destructive business. As nations gather to discuss the future of the industry, the Biden administration should join 25 other countries, including Canada and Mexico, in support of a global moratorium on deep-sea mining. For the sake of our ocean—and for all life on Earth that depends on it.

Five thousand new species were discovered earlier this year on a single research expedition to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone—a 1.7 million square mile area between Hawaii and Mexico. A steady stream of studies like this one reveal that from the darkest depths to the shallows by our shores, there are a multitude of undiscovered species in our oceans.

But the Clarion-Clipperton Zone also possesses a high concentration of minerals, and has therefore captured the eye of a risky new industry: deep-sea mining. If zones like this one are opened up for full-scale industrial mining, numerous newly discovered and undiscovered species will be at risk. Mining threatens to permanently destroy vast sea floors, undersea mountains, and otherworldly hydrothermal vents.

We urge U.S. President Joe Biden and his administration to call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, and stop this destructive industry from wreaking havoc on our seas. Right now, mining the deep seas is largely illegal under international laws, which means we can still prevent the destruction of untouched ocean areas and the multitudes they contain.

In short, deep-sea mining is an unnecessary threat to our global climate, the stability of our oceans, and the economy that depends on them.

But time is running out. At the end of July, nations will come together in Kingston, Jamaica at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which oversees commercial seabed mining in international waters, to advance draft mining rules. While the U.S. is not a member of the ISA, a U.S. moratorium would send a strong message that it supports neither destructive seabed mining nor creating a new domestic market for minerals sourced from the ocean. Twenty-five member states of the ISA—along with an increasing number of environmental, scientific, and Indigenous groups—already support a moratorium.

Yet the ISA is on track to allow deep-sea mining to begin–with increasingly lax regulation. In a recent draft of the ISA’s Mining Code, environmental protections for sensitive ecosystems had been stripped out. And in a breach of transparency norms, the identities of those proposing language to accelerate the approval of commercial mining licenses were omitted.

Some in the U.S. Congress are encouraging the acceleration of industrial deep-sea mining in U.S. federal waters, and federal agencies are preparing for the possibility of mining applications in the country, including an area off the Southeast U.S. called the Blake Plateau. This region, still scarred from test mining in the 1970s, is home to one of the world’s largest deep-sea coral reefs. Fishermen have long sought to protect this area, but deep-sea mining could put that protection—and their livelihoods—at risk. Last year, fishing industry groups joined the chorus of opposition to deep-sea mining.

The harm caused by deep-sea mining isn’t restricted to the sea floor. It will impact the entire water column top to bottom, and everyone and everything relying on it. Byproducts from mining could expose economically and culturally important species such as tunas to toxic sediment plumes, potentially contaminating fisheries. These plumes risk damaging known and unknown species at every depth, including those that sequester and transfer massive amounts of carbon.

Pro-mining interests argue that deep-sea minerals are needed for green energy technologies, like batteries for electric vehicles and solar panels, to meet future demand and mitigate climate change. We must not give in to this false choice between oceans and climate, and instead recognize that protecting our ocean is an equally important piece of keeping our planet habitable.

The ocean plays a critical role in global climate stability. Ocean creatures are vital strands in a delicate web of life that touches all of us. They are critical to coastal communities and economies, a potential source of game-changing medicines, and each plays a part in natural processes that help to regulate our climate.

Undermining ocean health to pursue potential mineral deposits is simply unnecessary. Demand for seabed minerals like nickel, copper, and cobalt is expected to level off or decline as clean energy technologies evolve and recycling capabilities improve. For example, batteries without seabed minerals now make up 36% of the electric vehicle market, and this is expected to increase to 60% by 2030.

In short, deep-sea mining is an unnecessary threat to our global climate, the stability of our oceans, and the economy that depends on them.

President Biden’s administration must make it clear that U.S. waters are not open for this destructive business. As nations gather to discuss the future of the industry, the Biden administration should join 25 other countries, including Canada and Mexico, in support of a global moratorium on deep-sea mining. For the sake of our ocean—and for all life on Earth that depends on it.