May, 24 2022, 11:20am EDT

For Immediate Release

Contact:

Sharon Selvaggio, Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, (503) 704-0327, sharon.selvaggio@xerces.org

Scott Hoffman Black, Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, (503) 449-3792, scott.black@xerces.org

Andrew Missel, Advocates for the West, (503) 914-6388, amissel@advocateswest.org

Lori Ann Burd, Center for Biological Diversity, (971) 717-6405, laburd@biologicaldiversity.org

Lawsuit Launched Challenging USDA's Failure to Protect Endangered Species From Insecticide Sprays Over Millions of Acres in U.S. West

The Xerces Society and Center for Biological Diversity filed a notice of intent today to sue the U.S. Department of Agriculture's secretive Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service for failing to properly consider harms to endangered species caused by insecticide spraying across millions of acres of western grasslands.

APHIS oversees and funds the application of insecticides on rangelands in 17 states to prevent native grasshoppers from competing with livestock for forage.

WASHINGTON

The Xerces Society and Center for Biological Diversity filed a notice of intent today to sue the U.S. Department of Agriculture's secretive Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service for failing to properly consider harms to endangered species caused by insecticide spraying across millions of acres of western grasslands.

APHIS oversees and funds the application of insecticides on rangelands in 17 states to prevent native grasshoppers from competing with livestock for forage.

The main insecticide sprayed is diflubenzuron, which kills insects in their immature stages. It is typically sprayed from airplanes over areas of at least 10,000 acres. Studies have shown the insecticide reduces populations of bees, butterflies, beetles and a wide variety of other insects. Aquatic invertebrates consumed by endangered fish and trout are also vulnerable.

Grassland ecosystems are home to many endangered and threatened species, including flowering plants, mollusks and many different mammals. Several once-common species on rangelands, including greater sage grouse, monarch butterflies and western bumblebees are in steep decline and are the focus of conservation efforts, including possible listing under the Endangered Species Act. Many protected species depend directly on insects for their food or for pollination.

"Xerces doesn't enter into lawsuits lightly, but in this case the risks are too great," said Scott Black, executive director at the Xerces Society. "Over 80% of animals in grasslands are insects. When these are harmed by insecticide sprays, it could cause a cascade effect to the many endangered grassland species that rely on insects to survive."

Endangered species like yellow-billed cuckoos, black-footed ferrets, bull trout, Ute ladies'-tresses orchids, Oregon spotted frogs and Spalding's catchflies are present in multiple states in which the insecticide spraying program operates. But APHIS has failed to properly consider how the widespread insecticide use may harm these species across their range, as required under the Endangered Species Act.

"The last time APHIS completed a programmatic look at how its rangeland pesticides program affects endangered insects, birds and plants, Bill Clinton was in his first term as president, Friends was in its second season and Google did not yet exist," said Andrew Missel, staff attorney at Advocates for the West, who is representing the conservation groups. "It's way past time for APHIS to take a fresh look at how dousing hundreds of thousands of acres across the West with pesticides impacts the species that need the most protection."

Other insecticides approved for use in the spraying program include highly toxic carbaryl and malathion and a newer insecticide, chlorantraniliprole. The Environmental Protection Agency has determined that carbaryl is likely to harm 1,640 listed species, or 91% of all endangered plants and animals and malathion is likely to harm 1,835 listed species, or 97% of all endangered plants and animals. Chlorantraniliprole is a systemic pesticide, meaning it is absorbed by plants' leaves, pollen and nectar, exposing bees and butterflies for an extended time. Studies show it is highly toxic to monarch butterflies and other caterpillars.

"It's outrageous that amid our heartbreaking extinction crisis, APHIS continues to give itself carte blanche to spray incredibly toxic poisons on millions of acres of wildlife habitat throughout the West," said Lori Ann Burd, director of environmental health at the Center for Biological Diversity. "They've made a habit of refusing to follow the law and now we're going to hold them accountable."

The states in which the insecticide spraying is approved include Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.

Federal agencies are required to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service when they undertake projects that may affect listed species, yet APHIS and the Service have not completed programmatic consultation for grassland insecticides program for 27 years. Since then, many species potentially affected by the program have been listed as endangered, including bull trout, northern Idaho ground squirrels, northern long-eared bats, Preble's meadow jumping mice and Oregon spotted frogs.

Beyond impacts to federally listed species, APHIS's program poses larger risks to grassland ecosystems. Insects are a critical, often overlooked, part of a functioning planet and society. Most birds, freshwater fish and mammals consume insects as food. People and wildlife also depend on insect pollination for fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds. These ecological contributions generate significant monetary value; one study found that insects contribute more than $70 billion per year to the U.S. economy.

The public supports protection for wildlife and is especially concerned with the welfare of pollinators, which are negatively affected by these spray programs. Eighty percent of western voters agree that loss of pollinators is a serious problem, according to a 2020 Colorado College poll. This concern held true in every state and across all types of communities: cities (85%), suburbs (81%), small towns (77%), and rural areas (76%).

At the Center for Biological Diversity, we believe that the welfare of human beings is deeply linked to nature — to the existence in our world of a vast diversity of wild animals and plants. Because diversity has intrinsic value, and because its loss impoverishes society, we work to secure a future for all species, great and small, hovering on the brink of extinction. We do so through science, law and creative media, with a focus on protecting the lands, waters and climate that species need to survive.

(520) 623-5252LATEST NEWS

‘Don't Give the Pentagon $1 Trillion,’ Critics Say as House Passes Record US Military Spending Bill

"From ending the nursing shortage to insuring uninsured children, preventing evictions, and replacing lead pipes, every dollar the Pentagon wastes is a dollar that isn't helping Americans get by," said one group.

Dec 10, 2025

US House lawmakers on Wednesday approved a $900.6 billion military spending bill, prompting critics to highlight ways in which taxpayer funds could be better spent on programs of social uplift instead of perpetual wars.

The lower chamber voted 312-112 in favor of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year 2026, which will fund what President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans call a "peace through strength" national security policy. The proposal now heads for a vote in the Senate, where it is also expected to pass.

Combined with $156 billion in supplemental funding included in the One Big Beautiful Bill signed in July by Trump, the NDAA would push military spending this fiscal year to over $1 trillion—a new record in absolute terms and a relative level unseen since World War II.

The House is about to vote on authorizing $901 billion in military spending, on top of the $156 billion included in the Big Beautiful Bill.70% of global military spending already comes from the US and its major allies.www.stephensemler.com/p/congress-s...

[image or embed]

— Stephen Semler (@stephensemler.bsky.social) December 10, 2025 at 1:16 PM

The Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) led opposition to the bill on Capitol Hill, focusing on what lawmakers called misplaced national priorities, as well as Trump's abuse of emergency powers to deploy National Guard troops in Democratic-controlled cities under pretext of fighting crime and unauthorized immigration.

Others sounded the alarm over the Trump administration's apparent march toward a war on Venezuela—which has never attacked the US or any other country in its nearly 200-year history but is rich in oil and is ruled by socialists offering an alternative to American-style capitalism.

"I will always support giving service members what they need to stay safe but that does not mean rubber-stamping bloated budgets or enabling unchecked executive war powers," CPC Deputy Chair Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) said on social media, explaining her vote against legislation that "pours billions into weapons systems the Pentagon itself has said it does not need."

"It increases funding for defense contractors who profit from global instability and it advances a vision of national security rooted in militarization instead of diplomacy, human rights, or community well-being," Omar continued.

"At a time when families in Minnesota’s 5th District are struggling with rising costs, when our schools and social services remain underfunded, and when the Pentagon continues to evade a clean audit year after year, Congress should be investing in people," she added.

The Congressional Equality Caucus decried the NDAA's inclusion of a provision banning transgender women from full participation in sports programs at US military academies:

The NDAA should invest in our military, not target minority communities for exclusion.While we're grateful that most anti-LGBTQI+ provisions were removed, the GOP kept one anti-trans provision in the final bill—and that's one too many.We're committed to repealing it.

[image or embed]

— Congressional Equality Caucus (@equality.house.gov) December 10, 2025 at 3:03 PM

Advocacy groups also denounced the legislation, with the Institute for Policy Studies' National Priorities Project (NPP) noting that "from ending the nursing shortage to insuring uninsured children, preventing evictions, and replacing lead pipes, every dollar the Pentagon wastes is a dollar that isn't helping Americans get by."

"The last thing Congress should do is deliver $1 trillion into the hands of [Defense] Secretary Pete Hegseth," NPP program director Lindsay Koshgarian said in a statement Wednesday. "Under Secretary Hegseth's leadership, the Pentagon has killed unidentified boaters in the Caribbean, sent the National Guard to occupy peaceful US cities, and driven a destructive and divisive anti-diversity agenda in the military."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Fed Cut Interest Rates But Can't Undo 'Damage Created by Trump's Chaos Economy,' Expert Says

"Working families are heading into the holidays feeling stretched, stressed, and far from jolly."

Dec 10, 2025

A leading economist and key congressional Democrat on Wednesday pointed to the Federal Reserve's benchmark interest rate cut as just the latest evidence of the havoc that President Donald Trump is wreaking on the economy.

The US central bank has a dual mandate to promote price stability and maximum employment. The Federal Open Market Committee may raise the benchmark rate to reduce inflation, or cut it to spur economic growth, including hiring. However, the FOMC is currently contending with a cooling job market and soaring costs.

After the FOMC's two-day monthly meeting, the divided committee announced a quarter-point reduction to 3.5-3.75%. It's the third time the panel has cut the federal funds rate in recent months after a pause during the early part of Trump's second term.

"Today's decision shows that the Trump economy is in a sorry state and that the Federal Reserve is concerned about a weakening job market," House Budget Committee Ranking Member Brendan Boyle (D-Pa.) said in a statement. "On top of a flailing job market, the president's tariffs—his national sales tax—continue to fuel inflation."

"To make matters worse, extreme Republican policies, including Trump's Big Ugly Law, are driving healthcare costs sharply higher," he continued, pointing to the budget package that the president signed in July. "I will keep fighting to lower costs and for an economy that works for every American."

Alex Jacquez, a former Obama administration official who is now chief of policy and advocacy at the Groundwork Collaborative, similarly said that "Trump's reckless handling of the economy has backed the Fed into a corner—stuck between rising costs and a weakening job market, it has no choice but to try and offer what little relief they can to consumers via rate cuts."

"But the Fed cannot undo the damage created by Trump's chaos economy," Jacquez added, "and working families are heading into the holidays feeling stretched, stressed, and far from jolly."

Thanks to the historically long federal government shutdown, the FOMC didn't have typical data—the consumer price index or jobs report—to inform Wednesday's decision. Instead, its new statement and projections "relied on 'available indicators,' which Fed officials have said include their own internal surveys, community contacts, and private data," Reuters reported.

"The most recent official data on unemployment and inflation is for September, and showed the unemployment rate rising to 4.4% from 4.3%, while the Fed's preferred measure of inflation also increased slightly to 2.8% from 2.7%," the news agency noted. "The Fed has a 2% inflation target, but the pace of price increases has risen steadily from 2.3% in April, a fact at least partly attributable to the pass-through of rising import taxes to consumers and a driving force behind the central bank's policy divide."

The lack of government data has also shifted journalists' attention to other sources, including the revelation from global payroll processing firm ADP that the US lost 32,000 jobs in November, as well as Gallup's finding last week that Americans' confidence in the economy has fallen by seven points over the past month and is now at its lowest level in over a year.

The Associated Press highlighted that the rate cut is "good news" for US job-seekers:

"Overall, we've seen a slowing demand for workers with employers not hiring the way they did a couple of years ago," said Cory Stahle, senior economist at the Indeed Hiring Lab. "By lowering the interest rate, you make it a little more financially reasonable for employers to hire additional people. Especially in some areas—like startups, where companies lean pretty heavily on borrowed money—that's the hope here."

Stahle acknowledged that it could take time for the rate cuts to filter down to employers and then to workers, but he said the signal of the reduction is also important.

"Beyond the size of the cut, it tells employers and job-seekers something about the Federal Reserve's priorities and focus. That they're concerned about the labor market and willing to step in and support the labor market. It's an assurance of the reserve's priorities."

The Federal Reserve is now projecting only one rate cut next year. During a Wednesday press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell pointed to the three cuts since September and said that "we are well positioned to wait to see how the economy evolves."

However, Powell is on his way out, with his term ending in May, and Trump signaled in a Tuesday interview with Politico that agreeing with immediate interest rate cuts is a litmus test for his next nominee to fill the role.

Trump—who embarked on a nationwide "affordability tour" this week after claiming last week that "the word 'affordability' is a Democrat scam"—also graded the US economy on his watch, giving it an A+++++.

US Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) responded: "Really? 60% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. 800,000 are homeless. Food prices are at record highs. Wages lag behind inflation. God help us when we have a B+++++ economy."

Keep ReadingShow Less

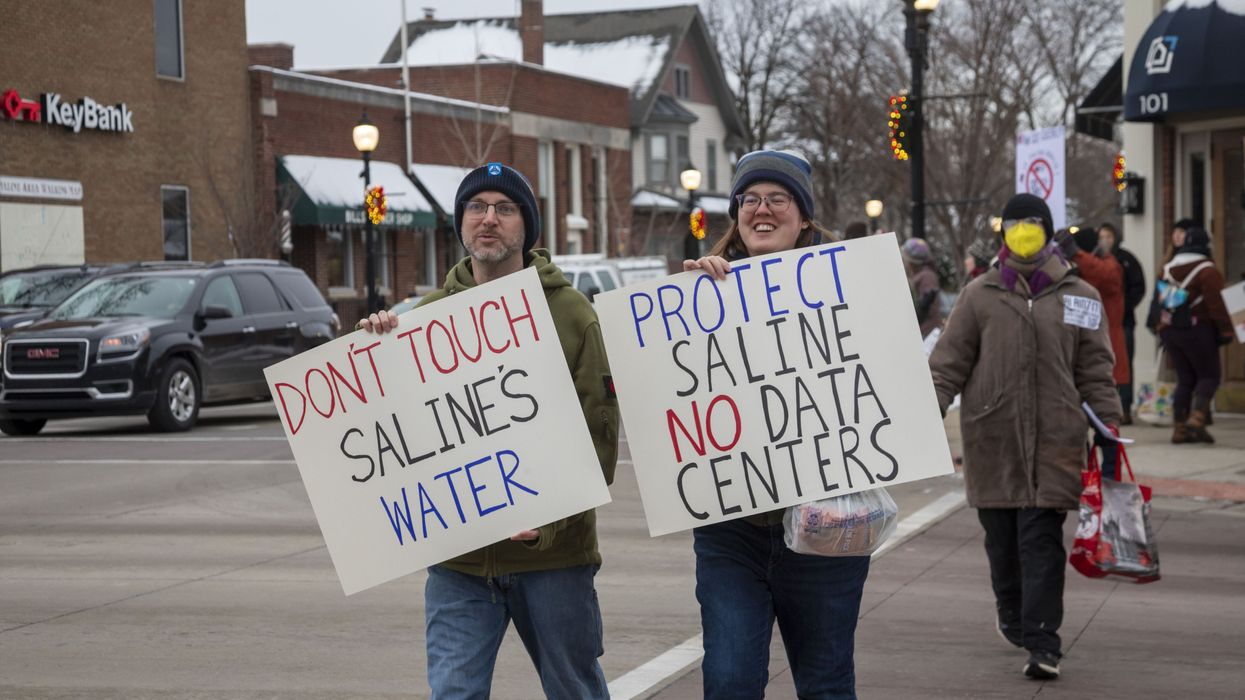

Sanders Champions Those Fighting Back Against Water-Sucking, Energy-Draining, Cost-Boosting Data Centers

Dec 10, 2025

Americans who are resisting the expansion of artificial intelligence data centers in their communities are up against local law enforcement and the Trump administration, which is seeking to compel cities and towns to host the massive facilities without residents' input.

On Wednesday, US Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) urged AI data center opponents to keep up the pressure on local, state, and federal leaders, warning that the rapid expansion of the multi-billion-dollar behemoths in places like northern Virginia, Wisconsin, and Michigan is set to benefit "oligarchs," while working people pay "with higher water and electric bills."

"Americans must fight back against billionaires who put profits over people," said the senator.

In a video posted on the social media platform X, Sanders pointed to two major AI projects—a $165 billion data center being built in Abilene, Texas by OpenAI and Oracle and one being constructed in Louisiana by Meta.

The centers are projected to use as much electricity as 750,000 homes and 1.2 million homes, respectively, and Meta's project will be "the size of Manhattan."

Hundreds gathered in Abilene in October for a "No Kings" protest where one local Democratic political candidate spoke out against "billion-dollar corporations like Oracle" and others "moving into our rural communities."

"They’re exploiting them for all of their resources, and they are creating a surveillance state,” said Riley Rodriguez, a candidate for Texas state Senate District 28.

In Holly Ridge, Lousiana, the construction of the world's largest data center has brought thousands of dump trucks and 18-wheelers driving through town on a daily basis, causing crashes to rise 600% and forcing a local school to shut down its playground due to safety concerns.

And people in communities across the US know the construction of massive data centers are only the beginning of their troubles, as electricity bills have surged this year in areas like northern Virginia, Illinois, and Ohio, which have a high concentration of the facilities.

The centers are also projected to use the same amount of water as 18.5 million homes normally, according to a letter signed by more than 200 environmental justice groups this week.

And in a survey of Pennsylvanians last week, Emerson College found 55% of respondents believed the expansion of AI will decrease the number of jobs available in their current industry. Sanders released an analysis in October showing that corporations including Amazon, Walmart, and UnitedHealth Group are already openly planning to slash jobs by shifting operations to AI.

In his video on Wednesday, Sanders applauded residents who have spoken out against the encroachment of Big Tech firms in their towns and cities.

"In community after community, Americans are fighting back against the data centers being built by some of the largest and most powerful corporations in the world," said Sanders. "They are opposing the destruction of their local environment, soaring electric bills, and the diversion of scarce water supplies."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular