SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Homes are partially toppled onto the beach after Hurricane Nicole came ashore on November 10, 2022 in Daytona Beach, Florida.

"This new study, using a new method, adds to the evidence that we certainly will face continuing changes in climate that intensify the impacts we are already feeling," said the lead author.

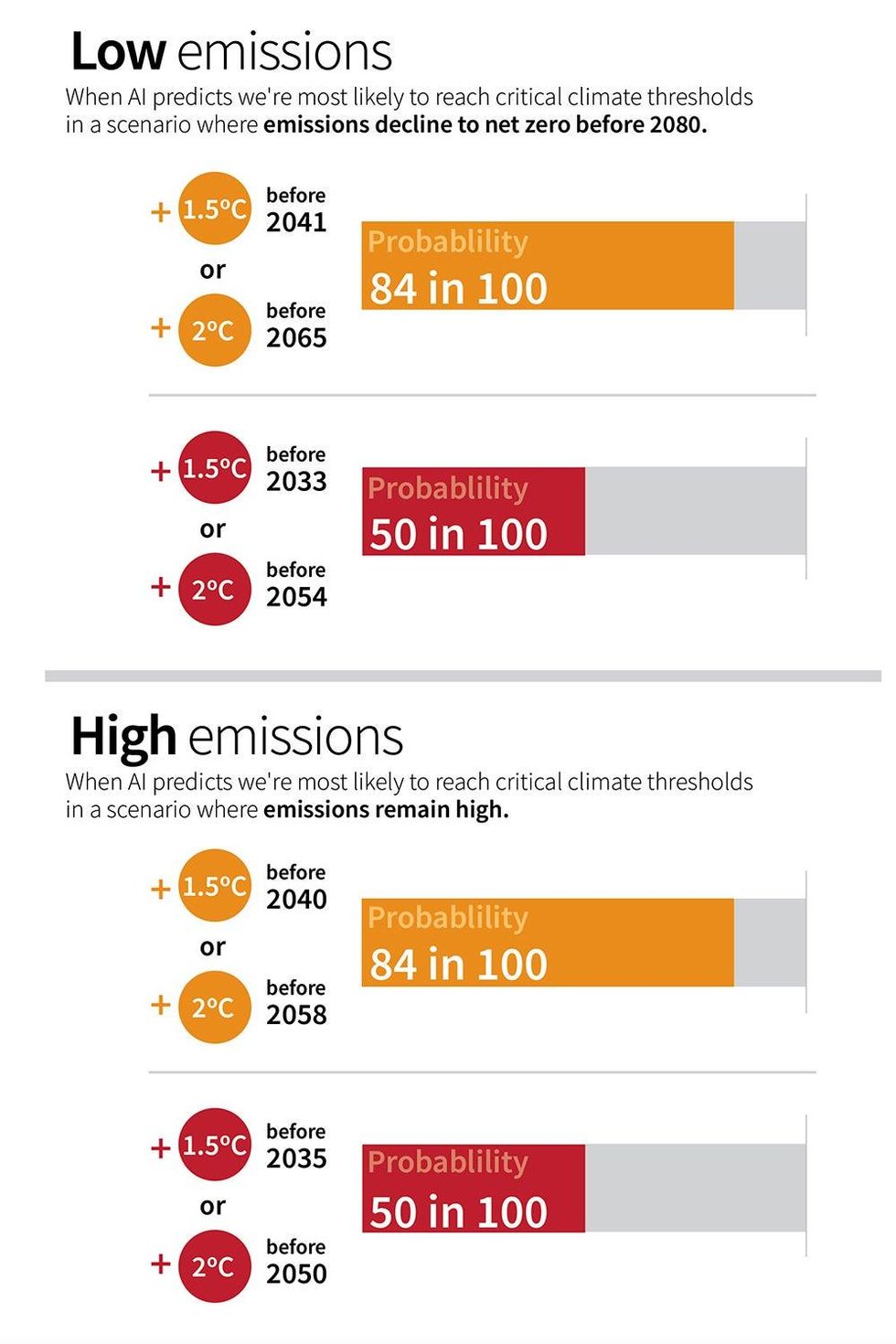

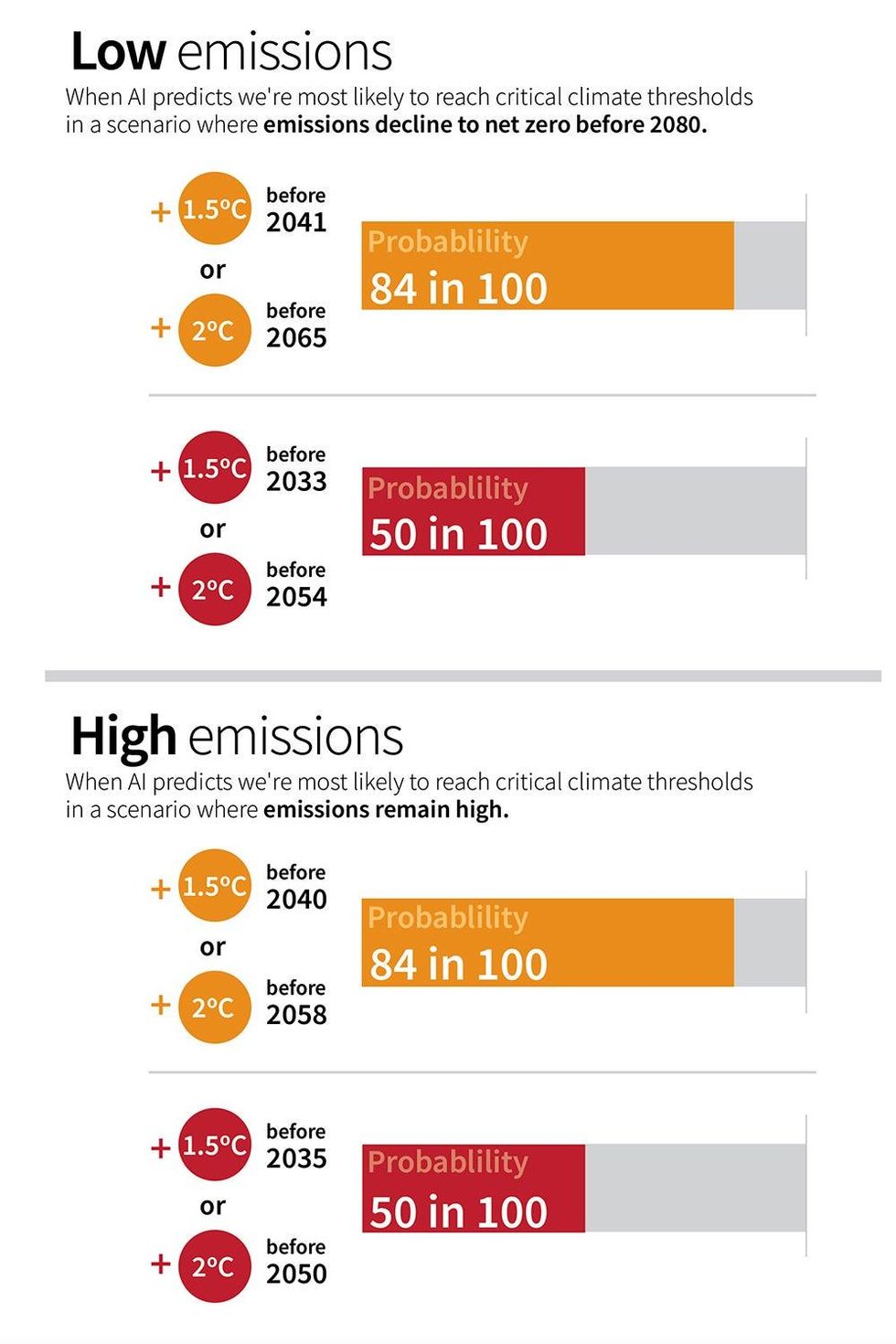

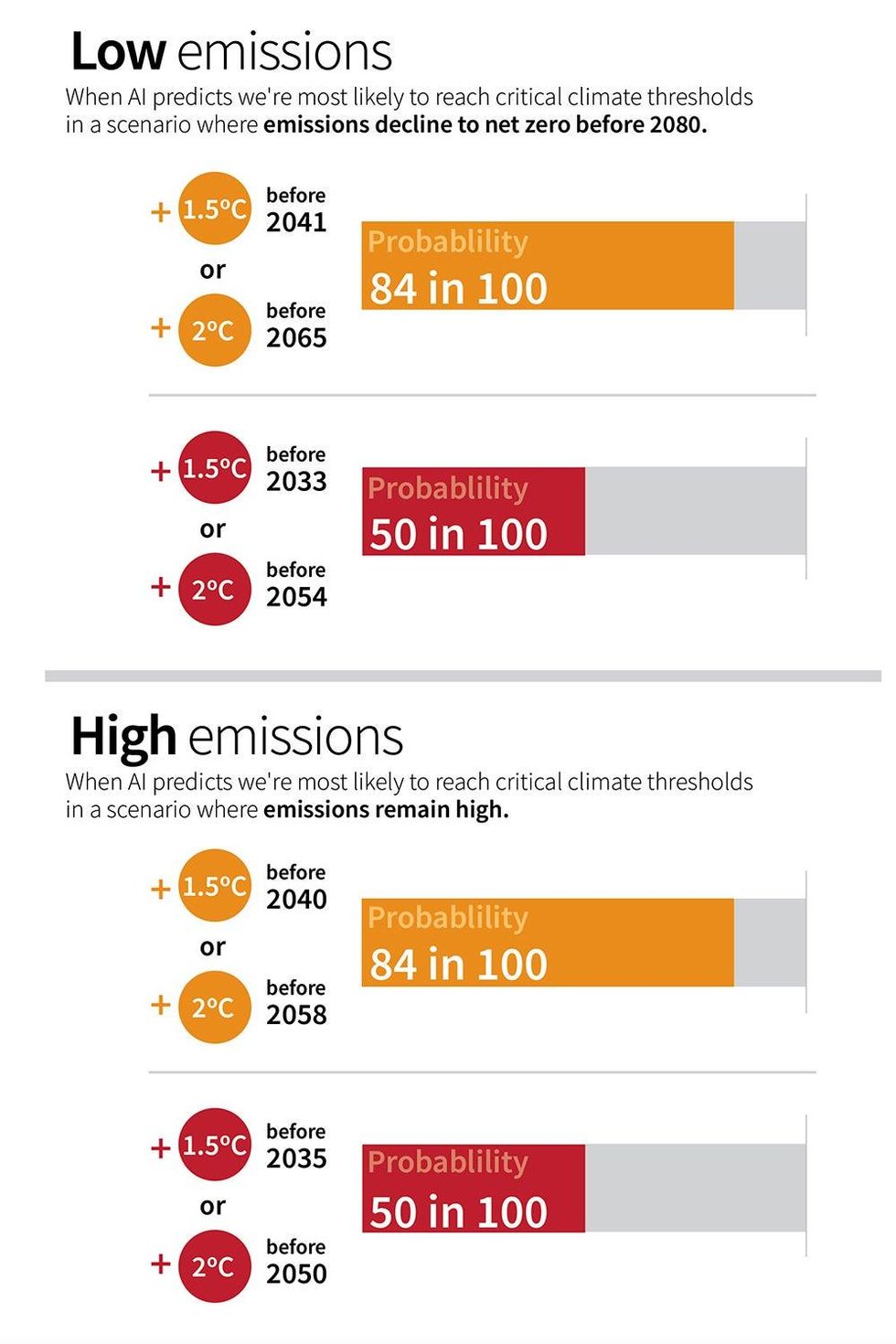

Even with ambitious action to reduce planet-heating emissions, the world could pass the two key temperature thresholds of the Paris climate agreement in the coming decades, according to new research that relied on artificial intelligence.

With the 2015 deal, nations agreed to work toward keeping global temperature rise this century "well below" 2°C and ultimately limiting it to 1.5°C. The study, published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used a type of AI known as a neural network to predict how likely it is that the world will breach both limits before 2100.

Already, the world has warmed by an average of about 1.1°C relative to preindustrial levels. Stanford University's Noah Diffenbaugh and Elizabeth Barnes of Colorado State University found that under both low and high emissions scenarios, there is a high probability of hitting 1.5°C sometime in the 2030s. There's also a high chance of hitting 2°C in the next few decades.

"We have very clear evidence of the impact on different ecosystems from the 1°C of global warming that's already happened," Diffenbaugh told The Guardian. "This new study, using a new method, adds to the evidence that we certainly will face continuing changes in climate that intensify the impacts we are already feeling."

"We confirm that the world is on the cusp of crossing the 1.5°C threshold," said Diffenbaugh. "Our AI model is quite convinced that there has already been enough warming that 2°C is likely to be exceeded if reaching net-zero emissions takes another half-century."

As CNN reported Monday:

The study's prediction is in line with previous models. In a major report published in 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that the world could cross the 1.5°C threshold "in the early 2030s."

Where the study departs from many current projections is in its estimates of when the world will cross the 2°C threshold.

While the IPCC projects that in a low emissions scenario, global temperature rises are unlikely to hit 2°C by the end of the century, the study returned more concerning results.

Diffenbaugh pointed out that various countries that support the Paris targets, along with nonstate actors, have set net-zero emissions targets for around mid-century. "Those net-zero pledges are often framed around achieving the Paris agreement 1.5°C goal," he said. "Our results suggest that those ambitious pledges might be needed to avoid 2°C."

For the study, Diffenbaugh and Barnes used outputs from global climate model simulations to train the neural network, then input previous observations of temperatures from across the globe to generate predictions. They tested the accuracy by seeing if the AI could correctly predict the current level of warming, or around 1.1°C—which it did.

"This was really the 'acid test' to see if the AI could predict the timing that we know has occurred," said Diffenbaugh. "We were pretty skeptical that this method would work until we saw that result. The fact that the AI has such high accuracy increases my confidence in its predictions of future warming."

According to The Associated Press:

Cornell University climate scientist Natalie Mahowald, who wasn't part of the Diffenbaugh study but was part of the IPCC, said the study makes sense, fits with what scientists know, but seems a bit more pessimistic.

There's a lot of power in using AI and in the future that may be shown to produce better projections, but more evidence is needed before concluding that, Mahowald said.

University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann, who edited the article, said that "the authors make an important and provocative contribution to the discussion over what is and is not achievable when it comes to limiting future warming below dangerous levels. That doesn't mean I necessarily agree with their conclusions."

Mann stressed the importance of distinguishing between physical and political obstacles to adequately slashing emissions, and that "physically, it is still possible to limit carbon emissions to levels that stay, with a reasonable likelihood, within the carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5°C."

"There is no climate 'cliff' at 1.5°C. Or 2°C," he added. "Rather, impacts increase with each fraction of a degree of warming. Limiting warming to 1.6°C is a whole lot better than allowing it to breach 2°C, and exceeding 1.5°C by a bit for a short period of time while stabilizing the climate below that level (a small 'overshoot') is a whole lot better than exceeding it by a lot for a long period of time (a big overshoot)."

The new AI-based research follows a study published last month which warned that even a temporary overshoot of the Paris targets could "significantly" raise the risk of triggering dangerous tipping points—specifically, the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the Amazon rainforest shifting to savannah, and the shutdown of the system of ocean currents that carries warm water from the tropics to the North Atlantic.

Despite the world already enduring destructive impacts of heating the planet—from extreme weather to melting glaciers and sea ice to oceans becoming hotter and more acidic—the Paris agreement countries refused to agree to rapidly phase out climate-wrecking fossil fuels during the Egyptian-hosted COP27 summit in November.

The next global climate conference, scheduled for later this year, is hosted by the United Arab Emirates—which is currently facing intense criticism for appointing Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, to lead COP28.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Even with ambitious action to reduce planet-heating emissions, the world could pass the two key temperature thresholds of the Paris climate agreement in the coming decades, according to new research that relied on artificial intelligence.

With the 2015 deal, nations agreed to work toward keeping global temperature rise this century "well below" 2°C and ultimately limiting it to 1.5°C. The study, published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used a type of AI known as a neural network to predict how likely it is that the world will breach both limits before 2100.

Already, the world has warmed by an average of about 1.1°C relative to preindustrial levels. Stanford University's Noah Diffenbaugh and Elizabeth Barnes of Colorado State University found that under both low and high emissions scenarios, there is a high probability of hitting 1.5°C sometime in the 2030s. There's also a high chance of hitting 2°C in the next few decades.

"We have very clear evidence of the impact on different ecosystems from the 1°C of global warming that's already happened," Diffenbaugh told The Guardian. "This new study, using a new method, adds to the evidence that we certainly will face continuing changes in climate that intensify the impacts we are already feeling."

"We confirm that the world is on the cusp of crossing the 1.5°C threshold," said Diffenbaugh. "Our AI model is quite convinced that there has already been enough warming that 2°C is likely to be exceeded if reaching net-zero emissions takes another half-century."

As CNN reported Monday:

The study's prediction is in line with previous models. In a major report published in 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that the world could cross the 1.5°C threshold "in the early 2030s."

Where the study departs from many current projections is in its estimates of when the world will cross the 2°C threshold.

While the IPCC projects that in a low emissions scenario, global temperature rises are unlikely to hit 2°C by the end of the century, the study returned more concerning results.

Diffenbaugh pointed out that various countries that support the Paris targets, along with nonstate actors, have set net-zero emissions targets for around mid-century. "Those net-zero pledges are often framed around achieving the Paris agreement 1.5°C goal," he said. "Our results suggest that those ambitious pledges might be needed to avoid 2°C."

For the study, Diffenbaugh and Barnes used outputs from global climate model simulations to train the neural network, then input previous observations of temperatures from across the globe to generate predictions. They tested the accuracy by seeing if the AI could correctly predict the current level of warming, or around 1.1°C—which it did.

"This was really the 'acid test' to see if the AI could predict the timing that we know has occurred," said Diffenbaugh. "We were pretty skeptical that this method would work until we saw that result. The fact that the AI has such high accuracy increases my confidence in its predictions of future warming."

According to The Associated Press:

Cornell University climate scientist Natalie Mahowald, who wasn't part of the Diffenbaugh study but was part of the IPCC, said the study makes sense, fits with what scientists know, but seems a bit more pessimistic.

There's a lot of power in using AI and in the future that may be shown to produce better projections, but more evidence is needed before concluding that, Mahowald said.

University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann, who edited the article, said that "the authors make an important and provocative contribution to the discussion over what is and is not achievable when it comes to limiting future warming below dangerous levels. That doesn't mean I necessarily agree with their conclusions."

Mann stressed the importance of distinguishing between physical and political obstacles to adequately slashing emissions, and that "physically, it is still possible to limit carbon emissions to levels that stay, with a reasonable likelihood, within the carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5°C."

"There is no climate 'cliff' at 1.5°C. Or 2°C," he added. "Rather, impacts increase with each fraction of a degree of warming. Limiting warming to 1.6°C is a whole lot better than allowing it to breach 2°C, and exceeding 1.5°C by a bit for a short period of time while stabilizing the climate below that level (a small 'overshoot') is a whole lot better than exceeding it by a lot for a long period of time (a big overshoot)."

The new AI-based research follows a study published last month which warned that even a temporary overshoot of the Paris targets could "significantly" raise the risk of triggering dangerous tipping points—specifically, the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the Amazon rainforest shifting to savannah, and the shutdown of the system of ocean currents that carries warm water from the tropics to the North Atlantic.

Despite the world already enduring destructive impacts of heating the planet—from extreme weather to melting glaciers and sea ice to oceans becoming hotter and more acidic—the Paris agreement countries refused to agree to rapidly phase out climate-wrecking fossil fuels during the Egyptian-hosted COP27 summit in November.

The next global climate conference, scheduled for later this year, is hosted by the United Arab Emirates—which is currently facing intense criticism for appointing Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, to lead COP28.

Even with ambitious action to reduce planet-heating emissions, the world could pass the two key temperature thresholds of the Paris climate agreement in the coming decades, according to new research that relied on artificial intelligence.

With the 2015 deal, nations agreed to work toward keeping global temperature rise this century "well below" 2°C and ultimately limiting it to 1.5°C. The study, published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used a type of AI known as a neural network to predict how likely it is that the world will breach both limits before 2100.

Already, the world has warmed by an average of about 1.1°C relative to preindustrial levels. Stanford University's Noah Diffenbaugh and Elizabeth Barnes of Colorado State University found that under both low and high emissions scenarios, there is a high probability of hitting 1.5°C sometime in the 2030s. There's also a high chance of hitting 2°C in the next few decades.

"We have very clear evidence of the impact on different ecosystems from the 1°C of global warming that's already happened," Diffenbaugh told The Guardian. "This new study, using a new method, adds to the evidence that we certainly will face continuing changes in climate that intensify the impacts we are already feeling."

"We confirm that the world is on the cusp of crossing the 1.5°C threshold," said Diffenbaugh. "Our AI model is quite convinced that there has already been enough warming that 2°C is likely to be exceeded if reaching net-zero emissions takes another half-century."

As CNN reported Monday:

The study's prediction is in line with previous models. In a major report published in 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that the world could cross the 1.5°C threshold "in the early 2030s."

Where the study departs from many current projections is in its estimates of when the world will cross the 2°C threshold.

While the IPCC projects that in a low emissions scenario, global temperature rises are unlikely to hit 2°C by the end of the century, the study returned more concerning results.

Diffenbaugh pointed out that various countries that support the Paris targets, along with nonstate actors, have set net-zero emissions targets for around mid-century. "Those net-zero pledges are often framed around achieving the Paris agreement 1.5°C goal," he said. "Our results suggest that those ambitious pledges might be needed to avoid 2°C."

For the study, Diffenbaugh and Barnes used outputs from global climate model simulations to train the neural network, then input previous observations of temperatures from across the globe to generate predictions. They tested the accuracy by seeing if the AI could correctly predict the current level of warming, or around 1.1°C—which it did.

"This was really the 'acid test' to see if the AI could predict the timing that we know has occurred," said Diffenbaugh. "We were pretty skeptical that this method would work until we saw that result. The fact that the AI has such high accuracy increases my confidence in its predictions of future warming."

According to The Associated Press:

Cornell University climate scientist Natalie Mahowald, who wasn't part of the Diffenbaugh study but was part of the IPCC, said the study makes sense, fits with what scientists know, but seems a bit more pessimistic.

There's a lot of power in using AI and in the future that may be shown to produce better projections, but more evidence is needed before concluding that, Mahowald said.

University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann, who edited the article, said that "the authors make an important and provocative contribution to the discussion over what is and is not achievable when it comes to limiting future warming below dangerous levels. That doesn't mean I necessarily agree with their conclusions."

Mann stressed the importance of distinguishing between physical and political obstacles to adequately slashing emissions, and that "physically, it is still possible to limit carbon emissions to levels that stay, with a reasonable likelihood, within the carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5°C."

"There is no climate 'cliff' at 1.5°C. Or 2°C," he added. "Rather, impacts increase with each fraction of a degree of warming. Limiting warming to 1.6°C is a whole lot better than allowing it to breach 2°C, and exceeding 1.5°C by a bit for a short period of time while stabilizing the climate below that level (a small 'overshoot') is a whole lot better than exceeding it by a lot for a long period of time (a big overshoot)."

The new AI-based research follows a study published last month which warned that even a temporary overshoot of the Paris targets could "significantly" raise the risk of triggering dangerous tipping points—specifically, the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the Amazon rainforest shifting to savannah, and the shutdown of the system of ocean currents that carries warm water from the tropics to the North Atlantic.

Despite the world already enduring destructive impacts of heating the planet—from extreme weather to melting glaciers and sea ice to oceans becoming hotter and more acidic—the Paris agreement countries refused to agree to rapidly phase out climate-wrecking fossil fuels during the Egyptian-hosted COP27 summit in November.

The next global climate conference, scheduled for later this year, is hosted by the United Arab Emirates—which is currently facing intense criticism for appointing Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, to lead COP28.