SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

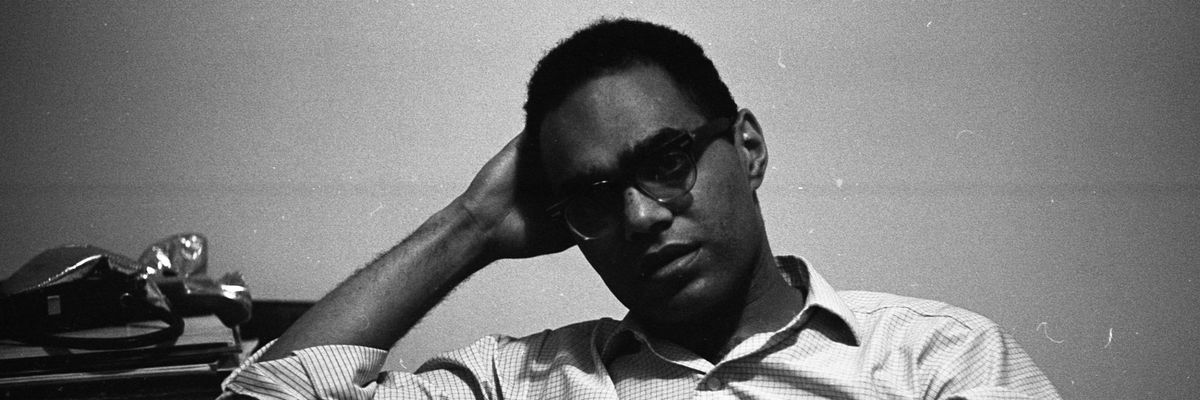

Civil rights activist and educator Bob Moses in New York City, 1964. (Photo: Robert Elfstrom/Villon Films/Getty Images)

Tributes to civil rights champion Bob Moses--the American educator and activist who as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups played a crucial role in the Civil Rights Movement's most consequential era--poured in following his death Sunday in Florida at the age of 86.

"Bob Moses was a Founding Father of the America we have not yet become."

--Waleed Shahid,

Justice Democrats

"Bob Moses was a giant, a strategist at the core of the civil rights movement," NAACP president Derrick Johnson said on Sunday. "Through his life's work, he bent the arc of the moral universe toward justice, making our world a better place. He fought for our right to vote, our most sacred right. He knew that justice, freedom, and democracy were not a state, but an ongoing struggle."

"So may his light continue to guide us as we face another wave of Jim Crow laws," Johnson added. "His example is more important now than ever...Rest in power, Bob."

Justice Democrats communications director and Nation editorial board member Waleed Shahid tweeted that "Bob Moses was a Founding Father of the America we have not yet become."

Former President Barack Obama tweeted that "Bob Moses was a hero of mine. His quiet confidence helped shape the civil rights movement, and he inspired generations of young people looking to make a difference."

Imani Perry, professor of African-American studies at Princeton University, called Moses her "model for organizing."

"Principled, intellectual, humble, deliberate, willing to work with all who come, never berating but consistently challenging," Perry tweeted in reference to Moses, who she also called "fun loving, kind, reflective, tender."

Climate activist and 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben called Moses "a true hero," tweeting that "on the list of bravest Americans ever, this man is very near the top."

Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.)--also an educator--said that "today, the world lost a giant" who "charted the path for teacher-activists to follow."

Robert Parris Moses was born in Harlem on January 23, 1935. After graduating from Hamilton College in Clinton, New York and earning a master's degree at Harvard in 1957, he started teaching math at the Horace Mann School in the Bronx. In 1960, he became field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which at the time was leading sit-ins to protest segregation at lunch counters in cities including Greensboro, North Carolina and Nashville.

That year, Moses was sent to Mississippi by mentor Ella Baker--who worked with civil rights leaders including W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Stokely Carmichael--to recruit students to participate in an SNCC conference in Atlanta. While traveling through southern Mississippi trying to register Black people to vote, Moses learned first-hand about the systemic disenfranchisement of African-Americans.

"I was taught about the denial of the right to vote behind the Iron Curtain in Europe; I never knew that there was denial of the right to vote behind a Cotton Curtain here in the United States," he said.

Attempting to register Black people to vote was perilous work in the South. When Moses was brutally beaten and arrested in Amite County, Mississippi, he filed charges against his assailant--who was subsequently acquitted by an all-white jury. While driving in Greenwood, Mississippi with activists James Travis and Randolph Blackwell in 1963, gunmen opened fire on Moses' car, wounding Travis.

"We were all within inches of being killed," Moses said at the time.

As co-director of the civil rights umbrella group Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), Moses played an instrumental role in the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, in which white student volunteers joined Black activists traveling the state to register African-American voters.

Explaining his interracial approach to activism, Moses wrote that if you "bring the nation's children," then "the parents will have to focus on Mississippi."

In a statement following Moses' death, SNCC said that "at the heart of these efforts was SNCC's idea that people--ordinary people long denied this power--could take control of their lives. These were the people that Bob brought to the table to fight for a seat at it: maids, sharecroppers, day workers, barbers, beauticians, teachers, preachers, and many others from all walks of life."

A week after the first volunteers arrived in Oxford, James Chaney, a Black Mississippian, and white northerners Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan with at least the cooperation of local police while the activists were investigating a church burning in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 were the hard-won fruits of the labor of countless activists, among whom Moses stood out, despite his soft-spoken, low-key leadership style.

"Bob listened," veteran activist Tom Hayden wrote in 2003. "When people asked him what to do, he asked them what they thought. At mass meetings, he usually sat in the back. In group discussions, he mostly spoke last. He slept on floors, wore sharecroppers' overalls, shared the risks, took the blows, went to jail, dug in deeply."

Moses would later say that "leadership is there in the people."

"If you go out and work with your people, then the leadership will emerge," he insisted.

Moses was also instrumental in organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which challenged policy, favored by the "Dixiecrats," of sending only white delegates to national conventions. However, when President Lyndon B. Johnson blocked the MFPD delegation--which included activists Fannie Lou Hamer, E.W. Steptoe, Victoria Gray, and others--to the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Moses grew increasingly disillusioned with U.S. politics. In 1965 he bitterly declared that "you cannot trust the system--I will have nothing to do with the political system any longer."

"We weren't just up against the Klan, or a mob of ignorant whites," Moses later wrote in his book, Radical Equations: Math Literacy and Civil Rights, "but political arrangements and expediencies that went all the way to Washington, D.C."

Like King, Moses was a pacifist and opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam. Speaking at the first major anti-war protest in Washington, D.C. in April 1965, he said that "the prosecutors of the war were the same people who refused to protect civil rights in the South."

"The questions that we think face the country are questions which in one sense are much deeper than civil rights," Moses told students at Stanford University in 1964. "They're questions which go very much to the bottom of mankind and people. They're questions which have repercussions in terms of a whole international affairs and relations. They're questions which go to the very root of our society. What kind of society will we be?"

King, who was assassinated in 1968, called Moses' "contribution to the freedom struggle in America" an "inspiration."

Moses' anti-war activism alienated him from many white liberals, and he eventually left SNCC and severed all relationships with white people. He traveled to Tanzania to avoid being drafted into the U.S. military, and after eight years of teaching in Africa he returned to Harvard to study for a PhD in the philosophy of mathematics.

During this period Moses was awarded a MacArthur Foundation "Genius" grant and used the funds to start the Algebra Project--an initiative to improve high school math literacy among low-income students--in 1982.

"In Mississippi in the 1960s, we worked to get sharecroppers to demand their right to vote and then act on that demand. The Algebra Project, at its core, is trying to do the same thing around education, using math," he explained in 2012.

Moses continued to teach late into his life. In addition to teaching high school math in Mississippi and Florida, he was a professor at Cornell University and a visiting scholar at Princeton, where he taught African-American studies with Tera Hunter.

Reacting to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police last May, Moses said that "it may be that the person who killed George Floyd was an aberration. But the system they were a part of, that protects them, and is as American as apple pie."

"So waking up to that--it's not clear whether the country is capable of waking up to that to its full extent," he told the New York Times. "It is revelatory that the pressure now is coming from within. It's been sparked by this one event, but the event really has opened up a crevasse, so to speak, through which all this history is pouring, like the Mississippi River onto the Delta."

"It's pouring into all the streams of TV, cable news, social media. So that is quite different," Moses added. "And the question is, can the country handle it? We don't know. I certainly don't know, at this moment, which way the country might flip. It can lurch backward as quickly as it can lurch forward."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Tributes to civil rights champion Bob Moses--the American educator and activist who as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups played a crucial role in the Civil Rights Movement's most consequential era--poured in following his death Sunday in Florida at the age of 86.

"Bob Moses was a Founding Father of the America we have not yet become."

--Waleed Shahid,

Justice Democrats

"Bob Moses was a giant, a strategist at the core of the civil rights movement," NAACP president Derrick Johnson said on Sunday. "Through his life's work, he bent the arc of the moral universe toward justice, making our world a better place. He fought for our right to vote, our most sacred right. He knew that justice, freedom, and democracy were not a state, but an ongoing struggle."

"So may his light continue to guide us as we face another wave of Jim Crow laws," Johnson added. "His example is more important now than ever...Rest in power, Bob."

Justice Democrats communications director and Nation editorial board member Waleed Shahid tweeted that "Bob Moses was a Founding Father of the America we have not yet become."

Former President Barack Obama tweeted that "Bob Moses was a hero of mine. His quiet confidence helped shape the civil rights movement, and he inspired generations of young people looking to make a difference."

Imani Perry, professor of African-American studies at Princeton University, called Moses her "model for organizing."

"Principled, intellectual, humble, deliberate, willing to work with all who come, never berating but consistently challenging," Perry tweeted in reference to Moses, who she also called "fun loving, kind, reflective, tender."

Climate activist and 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben called Moses "a true hero," tweeting that "on the list of bravest Americans ever, this man is very near the top."

Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.)--also an educator--said that "today, the world lost a giant" who "charted the path for teacher-activists to follow."

Robert Parris Moses was born in Harlem on January 23, 1935. After graduating from Hamilton College in Clinton, New York and earning a master's degree at Harvard in 1957, he started teaching math at the Horace Mann School in the Bronx. In 1960, he became field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which at the time was leading sit-ins to protest segregation at lunch counters in cities including Greensboro, North Carolina and Nashville.

That year, Moses was sent to Mississippi by mentor Ella Baker--who worked with civil rights leaders including W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Stokely Carmichael--to recruit students to participate in an SNCC conference in Atlanta. While traveling through southern Mississippi trying to register Black people to vote, Moses learned first-hand about the systemic disenfranchisement of African-Americans.

"I was taught about the denial of the right to vote behind the Iron Curtain in Europe; I never knew that there was denial of the right to vote behind a Cotton Curtain here in the United States," he said.

Attempting to register Black people to vote was perilous work in the South. When Moses was brutally beaten and arrested in Amite County, Mississippi, he filed charges against his assailant--who was subsequently acquitted by an all-white jury. While driving in Greenwood, Mississippi with activists James Travis and Randolph Blackwell in 1963, gunmen opened fire on Moses' car, wounding Travis.

"We were all within inches of being killed," Moses said at the time.

As co-director of the civil rights umbrella group Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), Moses played an instrumental role in the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, in which white student volunteers joined Black activists traveling the state to register African-American voters.

Explaining his interracial approach to activism, Moses wrote that if you "bring the nation's children," then "the parents will have to focus on Mississippi."

In a statement following Moses' death, SNCC said that "at the heart of these efforts was SNCC's idea that people--ordinary people long denied this power--could take control of their lives. These were the people that Bob brought to the table to fight for a seat at it: maids, sharecroppers, day workers, barbers, beauticians, teachers, preachers, and many others from all walks of life."

A week after the first volunteers arrived in Oxford, James Chaney, a Black Mississippian, and white northerners Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan with at least the cooperation of local police while the activists were investigating a church burning in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 were the hard-won fruits of the labor of countless activists, among whom Moses stood out, despite his soft-spoken, low-key leadership style.

"Bob listened," veteran activist Tom Hayden wrote in 2003. "When people asked him what to do, he asked them what they thought. At mass meetings, he usually sat in the back. In group discussions, he mostly spoke last. He slept on floors, wore sharecroppers' overalls, shared the risks, took the blows, went to jail, dug in deeply."

Moses would later say that "leadership is there in the people."

"If you go out and work with your people, then the leadership will emerge," he insisted.

Moses was also instrumental in organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which challenged policy, favored by the "Dixiecrats," of sending only white delegates to national conventions. However, when President Lyndon B. Johnson blocked the MFPD delegation--which included activists Fannie Lou Hamer, E.W. Steptoe, Victoria Gray, and others--to the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Moses grew increasingly disillusioned with U.S. politics. In 1965 he bitterly declared that "you cannot trust the system--I will have nothing to do with the political system any longer."

"We weren't just up against the Klan, or a mob of ignorant whites," Moses later wrote in his book, Radical Equations: Math Literacy and Civil Rights, "but political arrangements and expediencies that went all the way to Washington, D.C."

Like King, Moses was a pacifist and opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam. Speaking at the first major anti-war protest in Washington, D.C. in April 1965, he said that "the prosecutors of the war were the same people who refused to protect civil rights in the South."

"The questions that we think face the country are questions which in one sense are much deeper than civil rights," Moses told students at Stanford University in 1964. "They're questions which go very much to the bottom of mankind and people. They're questions which have repercussions in terms of a whole international affairs and relations. They're questions which go to the very root of our society. What kind of society will we be?"

King, who was assassinated in 1968, called Moses' "contribution to the freedom struggle in America" an "inspiration."

Moses' anti-war activism alienated him from many white liberals, and he eventually left SNCC and severed all relationships with white people. He traveled to Tanzania to avoid being drafted into the U.S. military, and after eight years of teaching in Africa he returned to Harvard to study for a PhD in the philosophy of mathematics.

During this period Moses was awarded a MacArthur Foundation "Genius" grant and used the funds to start the Algebra Project--an initiative to improve high school math literacy among low-income students--in 1982.

"In Mississippi in the 1960s, we worked to get sharecroppers to demand their right to vote and then act on that demand. The Algebra Project, at its core, is trying to do the same thing around education, using math," he explained in 2012.

Moses continued to teach late into his life. In addition to teaching high school math in Mississippi and Florida, he was a professor at Cornell University and a visiting scholar at Princeton, where he taught African-American studies with Tera Hunter.

Reacting to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police last May, Moses said that "it may be that the person who killed George Floyd was an aberration. But the system they were a part of, that protects them, and is as American as apple pie."

"So waking up to that--it's not clear whether the country is capable of waking up to that to its full extent," he told the New York Times. "It is revelatory that the pressure now is coming from within. It's been sparked by this one event, but the event really has opened up a crevasse, so to speak, through which all this history is pouring, like the Mississippi River onto the Delta."

"It's pouring into all the streams of TV, cable news, social media. So that is quite different," Moses added. "And the question is, can the country handle it? We don't know. I certainly don't know, at this moment, which way the country might flip. It can lurch backward as quickly as it can lurch forward."

Tributes to civil rights champion Bob Moses--the American educator and activist who as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups played a crucial role in the Civil Rights Movement's most consequential era--poured in following his death Sunday in Florida at the age of 86.

"Bob Moses was a Founding Father of the America we have not yet become."

--Waleed Shahid,

Justice Democrats

"Bob Moses was a giant, a strategist at the core of the civil rights movement," NAACP president Derrick Johnson said on Sunday. "Through his life's work, he bent the arc of the moral universe toward justice, making our world a better place. He fought for our right to vote, our most sacred right. He knew that justice, freedom, and democracy were not a state, but an ongoing struggle."

"So may his light continue to guide us as we face another wave of Jim Crow laws," Johnson added. "His example is more important now than ever...Rest in power, Bob."

Justice Democrats communications director and Nation editorial board member Waleed Shahid tweeted that "Bob Moses was a Founding Father of the America we have not yet become."

Former President Barack Obama tweeted that "Bob Moses was a hero of mine. His quiet confidence helped shape the civil rights movement, and he inspired generations of young people looking to make a difference."

Imani Perry, professor of African-American studies at Princeton University, called Moses her "model for organizing."

"Principled, intellectual, humble, deliberate, willing to work with all who come, never berating but consistently challenging," Perry tweeted in reference to Moses, who she also called "fun loving, kind, reflective, tender."

Climate activist and 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben called Moses "a true hero," tweeting that "on the list of bravest Americans ever, this man is very near the top."

Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.)--also an educator--said that "today, the world lost a giant" who "charted the path for teacher-activists to follow."

Robert Parris Moses was born in Harlem on January 23, 1935. After graduating from Hamilton College in Clinton, New York and earning a master's degree at Harvard in 1957, he started teaching math at the Horace Mann School in the Bronx. In 1960, he became field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which at the time was leading sit-ins to protest segregation at lunch counters in cities including Greensboro, North Carolina and Nashville.

That year, Moses was sent to Mississippi by mentor Ella Baker--who worked with civil rights leaders including W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Stokely Carmichael--to recruit students to participate in an SNCC conference in Atlanta. While traveling through southern Mississippi trying to register Black people to vote, Moses learned first-hand about the systemic disenfranchisement of African-Americans.

"I was taught about the denial of the right to vote behind the Iron Curtain in Europe; I never knew that there was denial of the right to vote behind a Cotton Curtain here in the United States," he said.

Attempting to register Black people to vote was perilous work in the South. When Moses was brutally beaten and arrested in Amite County, Mississippi, he filed charges against his assailant--who was subsequently acquitted by an all-white jury. While driving in Greenwood, Mississippi with activists James Travis and Randolph Blackwell in 1963, gunmen opened fire on Moses' car, wounding Travis.

"We were all within inches of being killed," Moses said at the time.

As co-director of the civil rights umbrella group Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), Moses played an instrumental role in the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, in which white student volunteers joined Black activists traveling the state to register African-American voters.

Explaining his interracial approach to activism, Moses wrote that if you "bring the nation's children," then "the parents will have to focus on Mississippi."

In a statement following Moses' death, SNCC said that "at the heart of these efforts was SNCC's idea that people--ordinary people long denied this power--could take control of their lives. These were the people that Bob brought to the table to fight for a seat at it: maids, sharecroppers, day workers, barbers, beauticians, teachers, preachers, and many others from all walks of life."

A week after the first volunteers arrived in Oxford, James Chaney, a Black Mississippian, and white northerners Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan with at least the cooperation of local police while the activists were investigating a church burning in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 were the hard-won fruits of the labor of countless activists, among whom Moses stood out, despite his soft-spoken, low-key leadership style.

"Bob listened," veteran activist Tom Hayden wrote in 2003. "When people asked him what to do, he asked them what they thought. At mass meetings, he usually sat in the back. In group discussions, he mostly spoke last. He slept on floors, wore sharecroppers' overalls, shared the risks, took the blows, went to jail, dug in deeply."

Moses would later say that "leadership is there in the people."

"If you go out and work with your people, then the leadership will emerge," he insisted.

Moses was also instrumental in organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which challenged policy, favored by the "Dixiecrats," of sending only white delegates to national conventions. However, when President Lyndon B. Johnson blocked the MFPD delegation--which included activists Fannie Lou Hamer, E.W. Steptoe, Victoria Gray, and others--to the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Moses grew increasingly disillusioned with U.S. politics. In 1965 he bitterly declared that "you cannot trust the system--I will have nothing to do with the political system any longer."

"We weren't just up against the Klan, or a mob of ignorant whites," Moses later wrote in his book, Radical Equations: Math Literacy and Civil Rights, "but political arrangements and expediencies that went all the way to Washington, D.C."

Like King, Moses was a pacifist and opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam. Speaking at the first major anti-war protest in Washington, D.C. in April 1965, he said that "the prosecutors of the war were the same people who refused to protect civil rights in the South."

"The questions that we think face the country are questions which in one sense are much deeper than civil rights," Moses told students at Stanford University in 1964. "They're questions which go very much to the bottom of mankind and people. They're questions which have repercussions in terms of a whole international affairs and relations. They're questions which go to the very root of our society. What kind of society will we be?"

King, who was assassinated in 1968, called Moses' "contribution to the freedom struggle in America" an "inspiration."

Moses' anti-war activism alienated him from many white liberals, and he eventually left SNCC and severed all relationships with white people. He traveled to Tanzania to avoid being drafted into the U.S. military, and after eight years of teaching in Africa he returned to Harvard to study for a PhD in the philosophy of mathematics.

During this period Moses was awarded a MacArthur Foundation "Genius" grant and used the funds to start the Algebra Project--an initiative to improve high school math literacy among low-income students--in 1982.

"In Mississippi in the 1960s, we worked to get sharecroppers to demand their right to vote and then act on that demand. The Algebra Project, at its core, is trying to do the same thing around education, using math," he explained in 2012.

Moses continued to teach late into his life. In addition to teaching high school math in Mississippi and Florida, he was a professor at Cornell University and a visiting scholar at Princeton, where he taught African-American studies with Tera Hunter.

Reacting to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police last May, Moses said that "it may be that the person who killed George Floyd was an aberration. But the system they were a part of, that protects them, and is as American as apple pie."

"So waking up to that--it's not clear whether the country is capable of waking up to that to its full extent," he told the New York Times. "It is revelatory that the pressure now is coming from within. It's been sparked by this one event, but the event really has opened up a crevasse, so to speak, through which all this history is pouring, like the Mississippi River onto the Delta."

"It's pouring into all the streams of TV, cable news, social media. So that is quite different," Moses added. "And the question is, can the country handle it? We don't know. I certainly don't know, at this moment, which way the country might flip. It can lurch backward as quickly as it can lurch forward."