SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Through an examination of industry-compiled fracking data and the US Department of Agriculture's official drought designations, AP reveals that by driving up the price of water and burdening already depleted aquifers and rivers, the high-polluting and water-intensive shale oil and gas removal process is placing an increasing threat on states currently suffering from ongoing drought.

"There is a new player for water, which is oil and gas. And certainly they are in a position to pay a whole lot more than we are," said fourth-generation farmer Kent Pepper of Mead, Colo., who has been forced to leave a number of his corn fields fallow this year because he cannot afford irrigation.

This news follows a recent study which found that nearly half of the country's fracking wells are located in water-stressed regions and 92 percent of wells located in extremely high-water-stress regions, leading to the inevitable escalation of what Grist refers to as "the West's water wars."

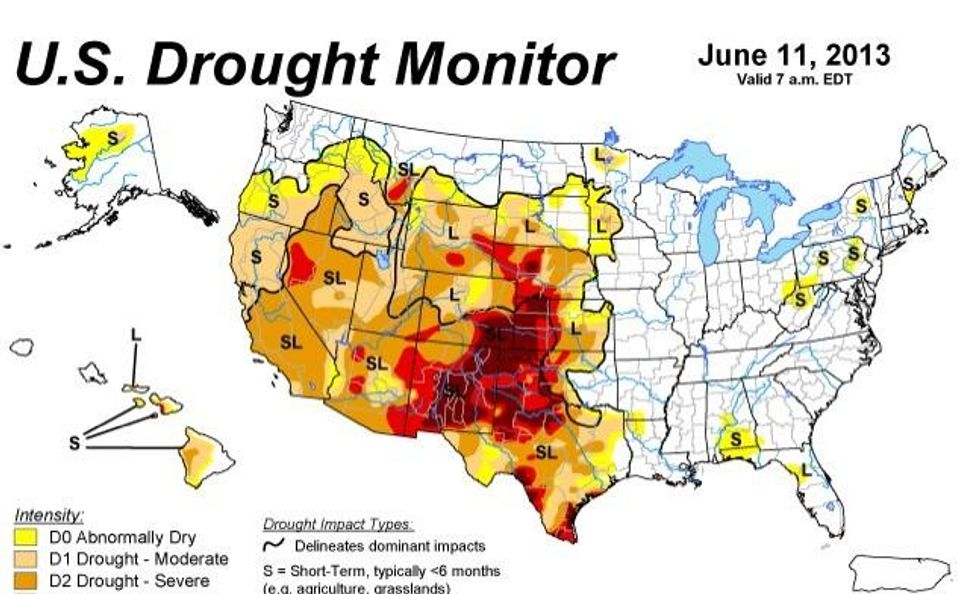

The states highlighted in the study--including Arkansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wyoming--fall within regions labeled by the most recent US Drought Monitor as suffering from "extreme" and "exceptional" drought conditions.

"The oil industry is doing the big fracks and pumping a substantial amount of water around here," said Ed Walker, general manager of the Wintergarden Groundwater Conservation District, which manages an aquifer that serves as the main water source for farmers and about 29,000 people in three counties.

"When you have a big problem like the drought and you add other [...] problems to it like all the fracking, then it only makes things worse," he continued.

AP continues:

In a normal year, Peppler said he would pay anywhere from $9 to $100 for an acre-foot of water in auctions held by cities with excess supplies. But these days, energy companies are paying some cities $1,200 to $2,900 per acre-foot. The Denver suburb of Aurora made a $9.5 million, five-year deal last summer to provide the oil company Anadarko 2.4 billion gallons of excess treated sewer water.

In South Texas, where drought has forced cotton farmers to scale back, local water officials said drillers are contributing to a drop in the water table in several areas.

For example, as much as 15,000 acre-feet of water are drawn each year from the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer to frack wells in the southern half of the Eagle Ford Shale, one of the nation's most profitable oil and gas fields.

That's equal to about half of the water recharged annually into the southern portion of the aquifer, which spans five counties that are home to about 330,000 people, said Ron Green, a scientist with the nonprofit Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

According to estimates by government and trade associations, the amount of water needed to "frack" a well varies greatly by region. In Texas, for instance, the average well requires up to 6 million gallons of water, while in California each well requires 80,000 to 300,000 gallons.

And depending on state and local water laws, this water is either drawn for free from underground aquifers or rivers, or is bought or leased from water districts, cities and farmers.

_____________________

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Through an examination of industry-compiled fracking data and the US Department of Agriculture's official drought designations, AP reveals that by driving up the price of water and burdening already depleted aquifers and rivers, the high-polluting and water-intensive shale oil and gas removal process is placing an increasing threat on states currently suffering from ongoing drought.

"There is a new player for water, which is oil and gas. And certainly they are in a position to pay a whole lot more than we are," said fourth-generation farmer Kent Pepper of Mead, Colo., who has been forced to leave a number of his corn fields fallow this year because he cannot afford irrigation.

This news follows a recent study which found that nearly half of the country's fracking wells are located in water-stressed regions and 92 percent of wells located in extremely high-water-stress regions, leading to the inevitable escalation of what Grist refers to as "the West's water wars."

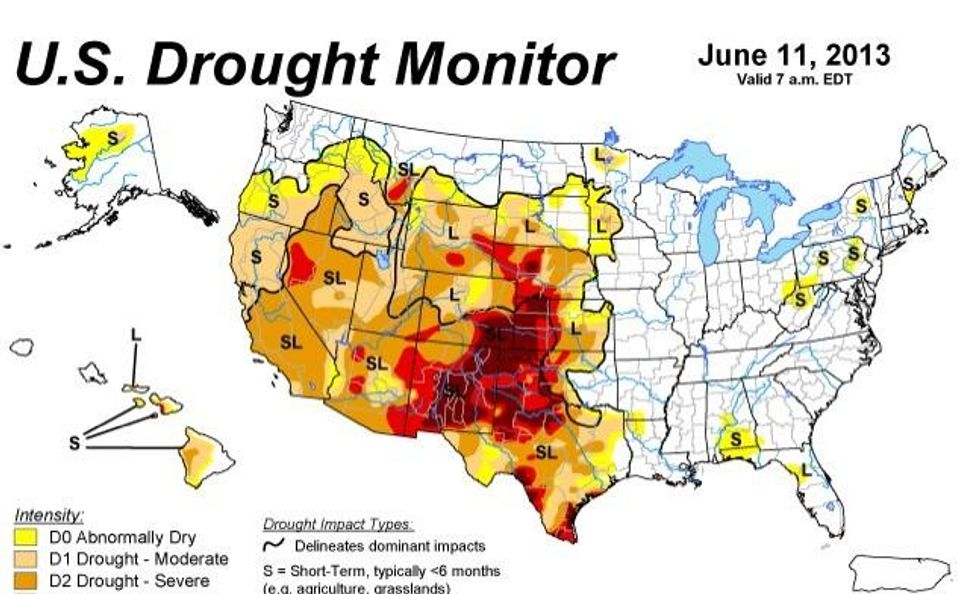

The states highlighted in the study--including Arkansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wyoming--fall within regions labeled by the most recent US Drought Monitor as suffering from "extreme" and "exceptional" drought conditions.

"The oil industry is doing the big fracks and pumping a substantial amount of water around here," said Ed Walker, general manager of the Wintergarden Groundwater Conservation District, which manages an aquifer that serves as the main water source for farmers and about 29,000 people in three counties.

"When you have a big problem like the drought and you add other [...] problems to it like all the fracking, then it only makes things worse," he continued.

AP continues:

In a normal year, Peppler said he would pay anywhere from $9 to $100 for an acre-foot of water in auctions held by cities with excess supplies. But these days, energy companies are paying some cities $1,200 to $2,900 per acre-foot. The Denver suburb of Aurora made a $9.5 million, five-year deal last summer to provide the oil company Anadarko 2.4 billion gallons of excess treated sewer water.

In South Texas, where drought has forced cotton farmers to scale back, local water officials said drillers are contributing to a drop in the water table in several areas.

For example, as much as 15,000 acre-feet of water are drawn each year from the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer to frack wells in the southern half of the Eagle Ford Shale, one of the nation's most profitable oil and gas fields.

That's equal to about half of the water recharged annually into the southern portion of the aquifer, which spans five counties that are home to about 330,000 people, said Ron Green, a scientist with the nonprofit Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

According to estimates by government and trade associations, the amount of water needed to "frack" a well varies greatly by region. In Texas, for instance, the average well requires up to 6 million gallons of water, while in California each well requires 80,000 to 300,000 gallons.

And depending on state and local water laws, this water is either drawn for free from underground aquifers or rivers, or is bought or leased from water districts, cities and farmers.

_____________________

Through an examination of industry-compiled fracking data and the US Department of Agriculture's official drought designations, AP reveals that by driving up the price of water and burdening already depleted aquifers and rivers, the high-polluting and water-intensive shale oil and gas removal process is placing an increasing threat on states currently suffering from ongoing drought.

"There is a new player for water, which is oil and gas. And certainly they are in a position to pay a whole lot more than we are," said fourth-generation farmer Kent Pepper of Mead, Colo., who has been forced to leave a number of his corn fields fallow this year because he cannot afford irrigation.

This news follows a recent study which found that nearly half of the country's fracking wells are located in water-stressed regions and 92 percent of wells located in extremely high-water-stress regions, leading to the inevitable escalation of what Grist refers to as "the West's water wars."

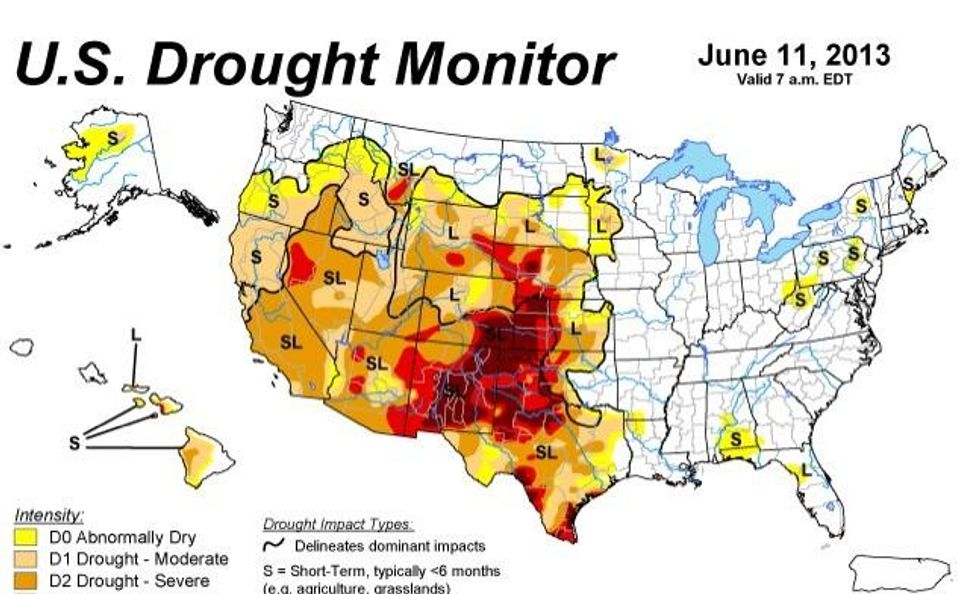

The states highlighted in the study--including Arkansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wyoming--fall within regions labeled by the most recent US Drought Monitor as suffering from "extreme" and "exceptional" drought conditions.

"The oil industry is doing the big fracks and pumping a substantial amount of water around here," said Ed Walker, general manager of the Wintergarden Groundwater Conservation District, which manages an aquifer that serves as the main water source for farmers and about 29,000 people in three counties.

"When you have a big problem like the drought and you add other [...] problems to it like all the fracking, then it only makes things worse," he continued.

AP continues:

In a normal year, Peppler said he would pay anywhere from $9 to $100 for an acre-foot of water in auctions held by cities with excess supplies. But these days, energy companies are paying some cities $1,200 to $2,900 per acre-foot. The Denver suburb of Aurora made a $9.5 million, five-year deal last summer to provide the oil company Anadarko 2.4 billion gallons of excess treated sewer water.

In South Texas, where drought has forced cotton farmers to scale back, local water officials said drillers are contributing to a drop in the water table in several areas.

For example, as much as 15,000 acre-feet of water are drawn each year from the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer to frack wells in the southern half of the Eagle Ford Shale, one of the nation's most profitable oil and gas fields.

That's equal to about half of the water recharged annually into the southern portion of the aquifer, which spans five counties that are home to about 330,000 people, said Ron Green, a scientist with the nonprofit Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

According to estimates by government and trade associations, the amount of water needed to "frack" a well varies greatly by region. In Texas, for instance, the average well requires up to 6 million gallons of water, while in California each well requires 80,000 to 300,000 gallons.

And depending on state and local water laws, this water is either drawn for free from underground aquifers or rivers, or is bought or leased from water districts, cities and farmers.

_____________________