Feb 26, 2015

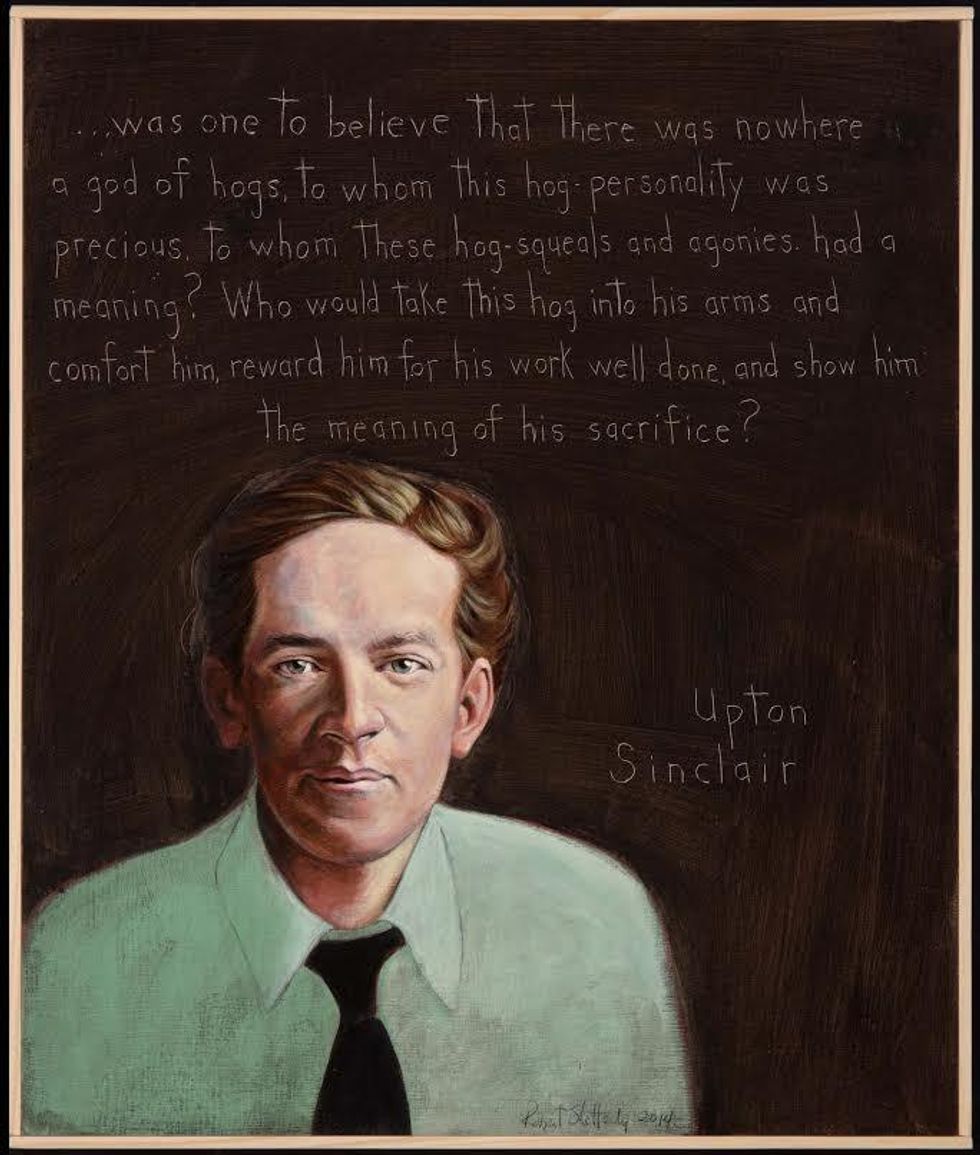

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time. This painting of Upton Sinclair, the famous novelist, journalist and social activist, is his latest portrait of those who dedicated their lives to equality, freedom and justice. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

Upton Sinclair did not say about The Jungle that it was the "most important and most dangerous book I have ever written." He said that about The Brass Check.

Self-published in 1919, The Brass Check chronicles how he was censored, excluded, and libeled as he tried to tell the truth of corporate malfeasance and anti-democratic influence in the United States. Sinclair presents case after case where the major newspapers in the U.S. "do not serve humanity, but property." He says that in terms of justice and democracy, there is no more important question for the American people than the objectivity of its press: "If the news is colored or doctored, then public opinion is betrayed and the national life is corrupted at its source." And, "It would be better for the people to go without shoes than without truth, but the people do not know this, and so continue to spend their money for shoes." But what Sinclair really advocated for was a press that told the truth and for fair wages so workers could afford shoes too.

In part of The Brass Check, Sinclair collects his accounts of being in Colorado in 1913-14 to report on the United Mine Workers of America strike against the Rockefeller-owned coal mines. It was those strikes, for safer working conditions, better pay, and several other issues, that culminated in the Ludlow Massacre where the Colorado National Guard (working for John D. Rockefeller, Jr.) attacked the miners' camp and killed women and children. Sinclair wrote dispatch after dispatch telling the miners' side of the story. The local and national newspapers--controlled by Rockefeller money--only published the mine owners' version events, reporting that all the violence was the work of the miners. Sinclair said:

When newspapers lie about a strike, they lie about every one of the strikers, and every one of these strikers and their wives and children and friends know it. When they see deliberate and long-continued campaigns to render them odious to the public, and to deprive them of their just rights, not merely as workers, but as citizens, a blaze of impotent fury is kindled in their hearts.

Sinclair also wrote about decent journalists who, under threat of firing by the newspaper owners, told only the corporate side of these stories. One of Sinclair's most famous quotes confronts this dilemma: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it."

Upton Sinclair was a lifelong socialist, a lifelong activist for the total gamut of social, economic and environmental justice issues in the U.S.. He was a feminist, as Lauren Coodley's excellent biography of him shows, at a time when few men were. He began two cooperative living societies so that women would be freed from some childcare and household duties to follow their dreams. Having grown up in a family with an abusive, alcoholic father, he supported temperance. He won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1943 for his series of anti-fascist novels. In 1934, Sinclair even ran for governor of California at the head of the End Poverty in California (EPIC) party.

His muckraking classic The Jungle about the horrendous conditions in the Chicago slaughterhouses pushed Congress to pass The Pure Food and Drug Act and The Meat Inspection Act. For a period after the publication of The Jungle in 1906, Sinclair was in great demand as a speaker all over the country. It seemed that more than anyone else he was determining what meat packing standards should be. In fact, the president, Teddy Roosevelt, got so annoyed at Sinclair's prominence that he pressured Frank Doubleday, Sinclair's publisher: "Tell Sinclair to go home and let me run the country for awhile."

I chose to use a quote from The Jungle on the Americans Who Tell the Truth portrait of Upton Sinclair. Perhaps the most famous passage in the book poetically details the horrible slaughtering process--the sound, the smells, the blood, the violence, the uncleanliness, the objectification of the animals and resultant dehumanization of the workers.

Sinclair writes, "... was one to believe that there was nowhere a god of hogs, to whom this hog-personality was precious, to whom these hog-squeals and agonies had a meaning? Who would take this hog into his arms and comfort him, reward him for his work well done, and show him the meaning of his sacrifice?"

Sinclair's intention with that quote was twofold - to insist that the reader honor the value of hog's life, at least enough to demand a humane death, and also to make the reader aware that the exploited workers in these slaughterhouses were being treated with little more respect than the hogs. Sinclair was delighted that meat packing regulations resulted from his book, but his primary intention had been to change the labor laws, to awaken the conscience of America to how its workers were being treated. He said, "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach." But working conditions in the slaughterhouses wouldn't change until the workers organized.

For the first two-thirds of the 20th Century there was surely no more broadly committed activist in the U.S. than Upton Sinclair. He wrote more than 80 books, publishing most of them himself because mainstream publishers disapproved of his ideas. He chose often to dramatize social issues in the form of novels on the theory that people would identify more with characters in good stories than be persuaded by argument.

By the way, Sinclair's title 'Brass Check' is a reference to the method of payment in a house of prostitution 100 years ago. The customer paid his money and was given a brass check to give to the woman he chose. Sinclair's point was that what passes for journalism is often little different than an exchange with a prostitute. Read more about Sinclair on the AWTT site. We were lucky to have Lauren Coodley herself write a short bio for us.

Join Us: News for people demanding a better world

Common Dreams is powered by optimists who believe in the power of informed and engaged citizens to ignite and enact change to make the world a better place. We're hundreds of thousands strong, but every single supporter makes the difference. Your contribution supports this bold media model—free, independent, and dedicated to reporting the facts every day. Stand with us in the fight for economic equality, social justice, human rights, and a more sustainable future. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover the issues the corporate media never will. Join with us today! |

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

Robert Shetterly

Robert Shetterly is a writer and artist who lives in Brooksville, Maine and the author of the book, "Americans Who Tell the Truth." Please visit the Americans Who Tell the Truth project's website, where posters of Howard Zinn, Rachel Carson, Edward Snowden, and scores of others are now available.

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time. This painting of Upton Sinclair, the famous novelist, journalist and social activist, is his latest portrait of those who dedicated their lives to equality, freedom and justice. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

Upton Sinclair did not say about The Jungle that it was the "most important and most dangerous book I have ever written." He said that about The Brass Check.

Self-published in 1919, The Brass Check chronicles how he was censored, excluded, and libeled as he tried to tell the truth of corporate malfeasance and anti-democratic influence in the United States. Sinclair presents case after case where the major newspapers in the U.S. "do not serve humanity, but property." He says that in terms of justice and democracy, there is no more important question for the American people than the objectivity of its press: "If the news is colored or doctored, then public opinion is betrayed and the national life is corrupted at its source." And, "It would be better for the people to go without shoes than without truth, but the people do not know this, and so continue to spend their money for shoes." But what Sinclair really advocated for was a press that told the truth and for fair wages so workers could afford shoes too.

In part of The Brass Check, Sinclair collects his accounts of being in Colorado in 1913-14 to report on the United Mine Workers of America strike against the Rockefeller-owned coal mines. It was those strikes, for safer working conditions, better pay, and several other issues, that culminated in the Ludlow Massacre where the Colorado National Guard (working for John D. Rockefeller, Jr.) attacked the miners' camp and killed women and children. Sinclair wrote dispatch after dispatch telling the miners' side of the story. The local and national newspapers--controlled by Rockefeller money--only published the mine owners' version events, reporting that all the violence was the work of the miners. Sinclair said:

When newspapers lie about a strike, they lie about every one of the strikers, and every one of these strikers and their wives and children and friends know it. When they see deliberate and long-continued campaigns to render them odious to the public, and to deprive them of their just rights, not merely as workers, but as citizens, a blaze of impotent fury is kindled in their hearts.

Sinclair also wrote about decent journalists who, under threat of firing by the newspaper owners, told only the corporate side of these stories. One of Sinclair's most famous quotes confronts this dilemma: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it."

Upton Sinclair was a lifelong socialist, a lifelong activist for the total gamut of social, economic and environmental justice issues in the U.S.. He was a feminist, as Lauren Coodley's excellent biography of him shows, at a time when few men were. He began two cooperative living societies so that women would be freed from some childcare and household duties to follow their dreams. Having grown up in a family with an abusive, alcoholic father, he supported temperance. He won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1943 for his series of anti-fascist novels. In 1934, Sinclair even ran for governor of California at the head of the End Poverty in California (EPIC) party.

His muckraking classic The Jungle about the horrendous conditions in the Chicago slaughterhouses pushed Congress to pass The Pure Food and Drug Act and The Meat Inspection Act. For a period after the publication of The Jungle in 1906, Sinclair was in great demand as a speaker all over the country. It seemed that more than anyone else he was determining what meat packing standards should be. In fact, the president, Teddy Roosevelt, got so annoyed at Sinclair's prominence that he pressured Frank Doubleday, Sinclair's publisher: "Tell Sinclair to go home and let me run the country for awhile."

I chose to use a quote from The Jungle on the Americans Who Tell the Truth portrait of Upton Sinclair. Perhaps the most famous passage in the book poetically details the horrible slaughtering process--the sound, the smells, the blood, the violence, the uncleanliness, the objectification of the animals and resultant dehumanization of the workers.

Sinclair writes, "... was one to believe that there was nowhere a god of hogs, to whom this hog-personality was precious, to whom these hog-squeals and agonies had a meaning? Who would take this hog into his arms and comfort him, reward him for his work well done, and show him the meaning of his sacrifice?"

Sinclair's intention with that quote was twofold - to insist that the reader honor the value of hog's life, at least enough to demand a humane death, and also to make the reader aware that the exploited workers in these slaughterhouses were being treated with little more respect than the hogs. Sinclair was delighted that meat packing regulations resulted from his book, but his primary intention had been to change the labor laws, to awaken the conscience of America to how its workers were being treated. He said, "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach." But working conditions in the slaughterhouses wouldn't change until the workers organized.

For the first two-thirds of the 20th Century there was surely no more broadly committed activist in the U.S. than Upton Sinclair. He wrote more than 80 books, publishing most of them himself because mainstream publishers disapproved of his ideas. He chose often to dramatize social issues in the form of novels on the theory that people would identify more with characters in good stories than be persuaded by argument.

By the way, Sinclair's title 'Brass Check' is a reference to the method of payment in a house of prostitution 100 years ago. The customer paid his money and was given a brass check to give to the woman he chose. Sinclair's point was that what passes for journalism is often little different than an exchange with a prostitute. Read more about Sinclair on the AWTT site. We were lucky to have Lauren Coodley herself write a short bio for us.

Robert Shetterly

Robert Shetterly is a writer and artist who lives in Brooksville, Maine and the author of the book, "Americans Who Tell the Truth." Please visit the Americans Who Tell the Truth project's website, where posters of Howard Zinn, Rachel Carson, Edward Snowden, and scores of others are now available.

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time. This painting of Upton Sinclair, the famous novelist, journalist and social activist, is his latest portrait of those who dedicated their lives to equality, freedom and justice. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

Upton Sinclair did not say about The Jungle that it was the "most important and most dangerous book I have ever written." He said that about The Brass Check.

Self-published in 1919, The Brass Check chronicles how he was censored, excluded, and libeled as he tried to tell the truth of corporate malfeasance and anti-democratic influence in the United States. Sinclair presents case after case where the major newspapers in the U.S. "do not serve humanity, but property." He says that in terms of justice and democracy, there is no more important question for the American people than the objectivity of its press: "If the news is colored or doctored, then public opinion is betrayed and the national life is corrupted at its source." And, "It would be better for the people to go without shoes than without truth, but the people do not know this, and so continue to spend their money for shoes." But what Sinclair really advocated for was a press that told the truth and for fair wages so workers could afford shoes too.

In part of The Brass Check, Sinclair collects his accounts of being in Colorado in 1913-14 to report on the United Mine Workers of America strike against the Rockefeller-owned coal mines. It was those strikes, for safer working conditions, better pay, and several other issues, that culminated in the Ludlow Massacre where the Colorado National Guard (working for John D. Rockefeller, Jr.) attacked the miners' camp and killed women and children. Sinclair wrote dispatch after dispatch telling the miners' side of the story. The local and national newspapers--controlled by Rockefeller money--only published the mine owners' version events, reporting that all the violence was the work of the miners. Sinclair said:

When newspapers lie about a strike, they lie about every one of the strikers, and every one of these strikers and their wives and children and friends know it. When they see deliberate and long-continued campaigns to render them odious to the public, and to deprive them of their just rights, not merely as workers, but as citizens, a blaze of impotent fury is kindled in their hearts.

Sinclair also wrote about decent journalists who, under threat of firing by the newspaper owners, told only the corporate side of these stories. One of Sinclair's most famous quotes confronts this dilemma: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it."

Upton Sinclair was a lifelong socialist, a lifelong activist for the total gamut of social, economic and environmental justice issues in the U.S.. He was a feminist, as Lauren Coodley's excellent biography of him shows, at a time when few men were. He began two cooperative living societies so that women would be freed from some childcare and household duties to follow their dreams. Having grown up in a family with an abusive, alcoholic father, he supported temperance. He won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1943 for his series of anti-fascist novels. In 1934, Sinclair even ran for governor of California at the head of the End Poverty in California (EPIC) party.

His muckraking classic The Jungle about the horrendous conditions in the Chicago slaughterhouses pushed Congress to pass The Pure Food and Drug Act and The Meat Inspection Act. For a period after the publication of The Jungle in 1906, Sinclair was in great demand as a speaker all over the country. It seemed that more than anyone else he was determining what meat packing standards should be. In fact, the president, Teddy Roosevelt, got so annoyed at Sinclair's prominence that he pressured Frank Doubleday, Sinclair's publisher: "Tell Sinclair to go home and let me run the country for awhile."

I chose to use a quote from The Jungle on the Americans Who Tell the Truth portrait of Upton Sinclair. Perhaps the most famous passage in the book poetically details the horrible slaughtering process--the sound, the smells, the blood, the violence, the uncleanliness, the objectification of the animals and resultant dehumanization of the workers.

Sinclair writes, "... was one to believe that there was nowhere a god of hogs, to whom this hog-personality was precious, to whom these hog-squeals and agonies had a meaning? Who would take this hog into his arms and comfort him, reward him for his work well done, and show him the meaning of his sacrifice?"

Sinclair's intention with that quote was twofold - to insist that the reader honor the value of hog's life, at least enough to demand a humane death, and also to make the reader aware that the exploited workers in these slaughterhouses were being treated with little more respect than the hogs. Sinclair was delighted that meat packing regulations resulted from his book, but his primary intention had been to change the labor laws, to awaken the conscience of America to how its workers were being treated. He said, "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach." But working conditions in the slaughterhouses wouldn't change until the workers organized.

For the first two-thirds of the 20th Century there was surely no more broadly committed activist in the U.S. than Upton Sinclair. He wrote more than 80 books, publishing most of them himself because mainstream publishers disapproved of his ideas. He chose often to dramatize social issues in the form of novels on the theory that people would identify more with characters in good stories than be persuaded by argument.

By the way, Sinclair's title 'Brass Check' is a reference to the method of payment in a house of prostitution 100 years ago. The customer paid his money and was given a brass check to give to the woman he chose. Sinclair's point was that what passes for journalism is often little different than an exchange with a prostitute. Read more about Sinclair on the AWTT site. We were lucky to have Lauren Coodley herself write a short bio for us.

We've had enough. The 1% own and operate the corporate media. They are doing everything they can to defend the status quo, squash dissent and protect the wealthy and the powerful. The Common Dreams media model is different. We cover the news that matters to the 99%. Our mission? To inform. To inspire. To ignite change for the common good. How? Nonprofit. Independent. Reader-supported. Free to read. Free to republish. Free to share. With no advertising. No paywalls. No selling of your data. Thousands of small donations fund our newsroom and allow us to continue publishing. Can you chip in? We can't do it without you. Thank you.