SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Workers in Durham, North Carolina go on strike to demand a $15 minimum wage on Tuesday February 16, 2020. (Photo: NC Raise Up/Twitter)

Opponents of raising the minimum wage have seized on a recent report by the Congressional Budget Office that estimated that increasing it to $15 an hour by 2025 would cause 1.4 million Americans to lose their jobs. These "significant job losses," according to a U.S. Chamber of Commerce vice president, provide reason enough to abandon the Biden administration's plan to help low-income workers.

First, it important to recognize the CBO also observes that income gains resulting from the wage increase are substantially greater than the reduction in income from job losses, thereby lifting nearly a million people out of poverty. Nonetheless, the report's assumptions about job losses are problematic -- significantly out of step with modern research on the subject.

A recent survey of the evidence in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, for instance, by the labor economist Alan Manning, carried an apt title that captures scholars' views far better: "The Elusive Employment Effects of Minimum Wages." Obviously, there is some point at which a high minimum wage would reduce employment, Manning explained, but the past few decades of research suggest "the currently observed range of minimum wages apparently does not include the turning-point." (Note that several states already are on paths toward a $15-per-hour minimum.)

I have also conducted multiple studies and reviews of the minimum-wage literature and agree that effects on employment are elusive. In 2019, for example, I was asked to undertake a review of minimum-wage scholarship for the British Treasury by the Conservative Party chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond. I concluded the weight of the evidence points to a fairly small impact of higher minimum wages on employment, even as they significantly increase the earnings of low paid workers.

What does "fairly small" mean, in this context? I looked at 55 different academic studies of episodes where a minimum wage was introduced or raised -- 36 in the United States, 11 in other developed countries. I found that for the typical study in the middle of the range of demonstrated effects, when average pay of affected workers rises by 10 percent after a mandated wage increase, their employment falls by at most 2 percent. But the studies that found job losses of that scale large tended to focus on narrow groups of affected workers (often teens or young adults) -- who may be particularly affected. When I focused on studies that looked at overall low-wage workforce, the evidence on job losses were minute: In those cases, the job loss from the same 10 percent increase in average wage of affected workers amounts to maybe 0.5 percent. At that level of job loss, the wage gains far offset the losses: The low-wage workforce as a whole is better off from the policy.

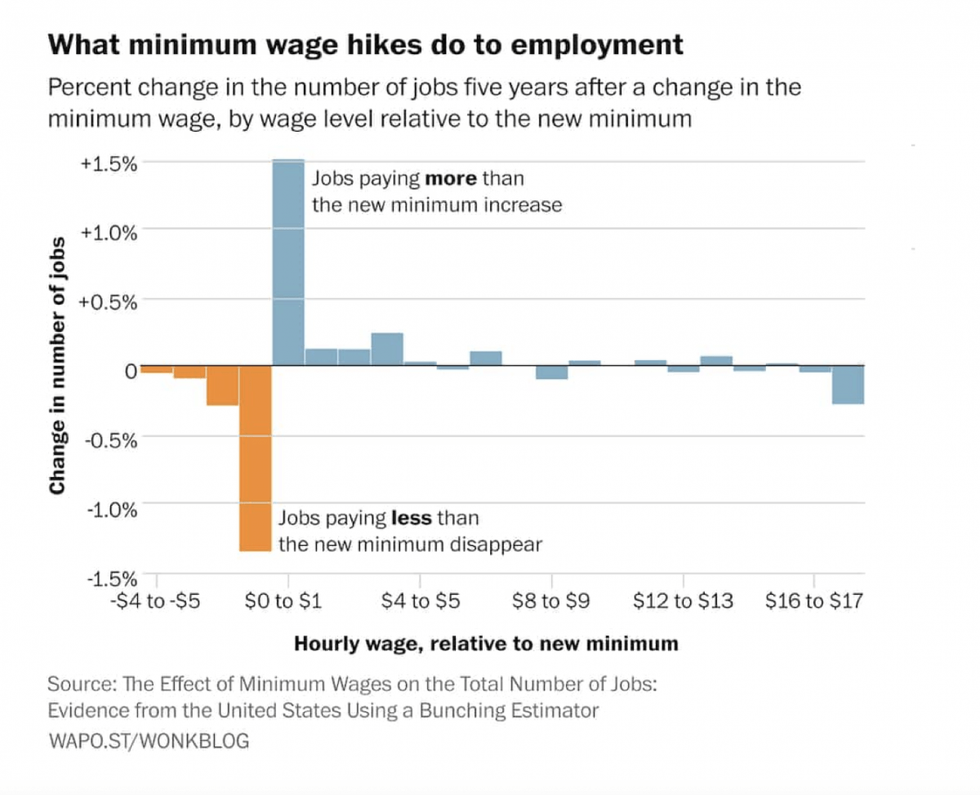

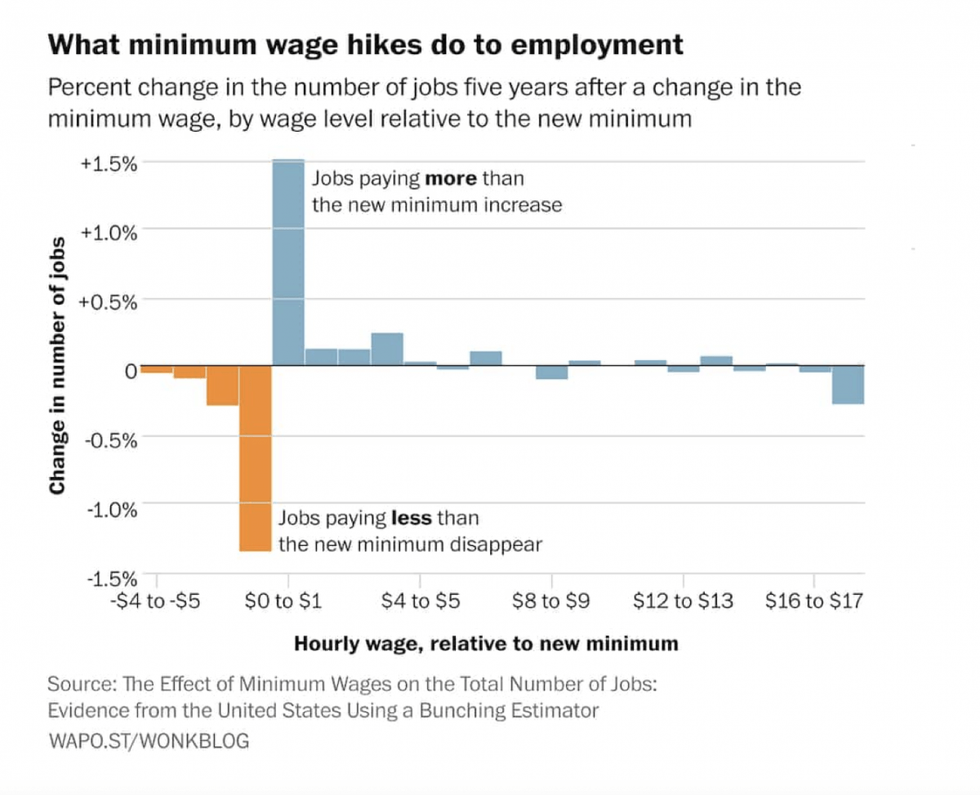

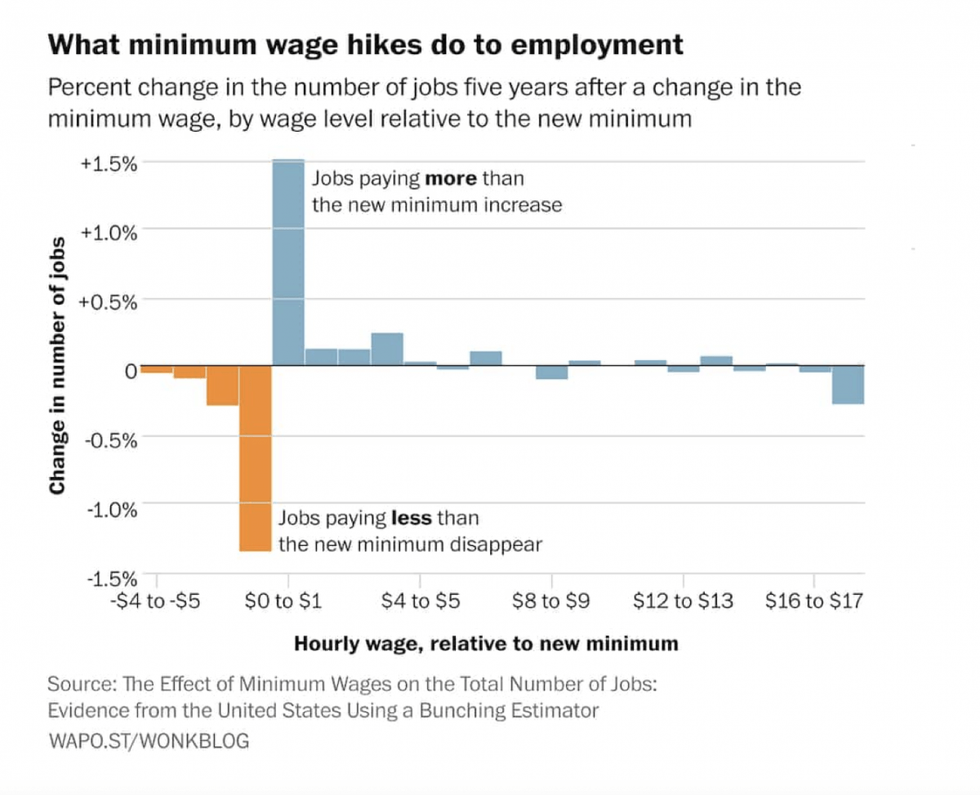

I and several colleagues conducted an even more thorough analysis in a 2019 study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics. We examined the effects of 138 state-level minimum wage increases from 1979 to 2016 in the United States. Comparing states that increased their minimum wages with states that did not, we found the change in employment (in the five years after the change occurred) took place in a narrow band around the new minimum wage: Understandably, jobs paying below the minimum decreased -- since wages rose. But at least as many jobs were added at the new, higher wage -- meaning jobs were upgraded, not destroyed. All told, the number of low wage jobs barely budged. This finding held when we looked at populations of special concern -- people with fewer educational credentials, for instance, or young workers. The finding held, as well, even when the minimum wage was set at a fairly high rate compared with the state's median wage (the highest being around 60 percent of the median wage). We found no effect on employment at levels significantly above the minimum wage.

We also explained why some other studies arrived at different (and, we think, less accurate) conclusions. Some, for instance, didn't account for regional booms and busts. When cities are economically thriving, wages get bid up, which can be misinterpreted as a drop in low-wage jobs. At the same time, the high cost of living in some booming cities can lead low-wage workers not to move there in the first place. One study that skeptics of the minimum wage like to cite, for example, conducted by researchers at the University of Washington, examined the effect of an increase in the minimum wage in Seattle from $9.47 per hour to as much as $11 in 2015 -- and then to as much as $13 in 2016. They found the second wage increase reduced hours worked in low-wage jobs by around 9 percent, while wages increased by about 3 percent -- for a net loss in the typical low-wage employees' earnings of about $125 per month. That's a big deal -- if true.

But that analysis didn't sufficiently take into account Seattle's status as an outlier "superstar" city, one where factors beside the minimum wage shape wages on the low end, in the ways described above. In fact, in a follow-up study, the same researchers, using a different methodology, found something much more in line with the consensus. In that analysis, they found the wage increase "brought benefits to many workers employed at the time, while leaving few employed workers worse off," as a New York Times summary of that paper put it.

In another study out this month, my co-author Attila Lindner and I built on our previous paper and studied the impact of 21 citywide minimum wages in places like Seattle, Los Angeles and Chicago. On average, the minimum wages in these cities were around 63 percent of the median, sometimes stretching up to 80 percent. Comparing those cities with others that had not raised the minimum wage, we found they saw stronger wage growth at the bottom than similar cities that did not raise the minimum. In a pattern that should be sounding familiar by now, after the minimum wage increase, there were fewer jobs paying right below the new minimum -- balanced by a roughly equal increase in jobs paying at or right above it. The wage increase essentially did not affect the overall number of jobs.

So how could the CBO come to the conclusion it did? For one thing, its report examines only 11 studies; these overlap with, but are not as comprehensive as, those I reviewed for the British Treasury report. (Tellingly, its sources include the first University of Washington study but not the follow-up that came to a more positive conclusion.) The CBO also changed its formula for summarizing the literature since the last time it looked at this question (in 2019). Back then, it looked at the median result of the 11 papers; this time, it placed more weight on those that found large job losses. The 2019 report was already somewhat out of step with the latest academic research, but the new one is even more so. It concludes that a 10 percent increase in average wages of affected workers would lead to a 4.8 percent fall in employment -- far above what I and others have found. That's how it arrives at the figure of 1.4 million lost jobs. Based on my own review of the overall evidence but still following CBO's approach, I would estimate that a national minimum wage increase to $15 per hour would lead to job losses under 500,000.

No doubt, moving to a $15 per hour minimum wage by 2025 would be a major policy change. As with any such change, it is important to acknowledge uncertainty and avoid overconfident projections. Is it possible that we may see more job losses from this policy than we have in the past? Yes. However, high-quality studies that have looked at the impact in low-wage, high-impact areas have yet to detect sharper job losses even when the minimum wage is close to 80 percent of the local area median income. (A $15 minimum by 2024 would probably produce a wage at around 80 percent of the median wage in a state like West Virginia, though it would exceed that level in some parts of the state.) At the same time, the risks of keeping the minimum wage too low -- in terms of increased poverty, inequality and racial injustice -- should be taken into account. Overall, the weight of the evidence suggests a $15 minimum wage would improve the lives of millions of American families.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Opponents of raising the minimum wage have seized on a recent report by the Congressional Budget Office that estimated that increasing it to $15 an hour by 2025 would cause 1.4 million Americans to lose their jobs. These "significant job losses," according to a U.S. Chamber of Commerce vice president, provide reason enough to abandon the Biden administration's plan to help low-income workers.

First, it important to recognize the CBO also observes that income gains resulting from the wage increase are substantially greater than the reduction in income from job losses, thereby lifting nearly a million people out of poverty. Nonetheless, the report's assumptions about job losses are problematic -- significantly out of step with modern research on the subject.

A recent survey of the evidence in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, for instance, by the labor economist Alan Manning, carried an apt title that captures scholars' views far better: "The Elusive Employment Effects of Minimum Wages." Obviously, there is some point at which a high minimum wage would reduce employment, Manning explained, but the past few decades of research suggest "the currently observed range of minimum wages apparently does not include the turning-point." (Note that several states already are on paths toward a $15-per-hour minimum.)

I have also conducted multiple studies and reviews of the minimum-wage literature and agree that effects on employment are elusive. In 2019, for example, I was asked to undertake a review of minimum-wage scholarship for the British Treasury by the Conservative Party chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond. I concluded the weight of the evidence points to a fairly small impact of higher minimum wages on employment, even as they significantly increase the earnings of low paid workers.

What does "fairly small" mean, in this context? I looked at 55 different academic studies of episodes where a minimum wage was introduced or raised -- 36 in the United States, 11 in other developed countries. I found that for the typical study in the middle of the range of demonstrated effects, when average pay of affected workers rises by 10 percent after a mandated wage increase, their employment falls by at most 2 percent. But the studies that found job losses of that scale large tended to focus on narrow groups of affected workers (often teens or young adults) -- who may be particularly affected. When I focused on studies that looked at overall low-wage workforce, the evidence on job losses were minute: In those cases, the job loss from the same 10 percent increase in average wage of affected workers amounts to maybe 0.5 percent. At that level of job loss, the wage gains far offset the losses: The low-wage workforce as a whole is better off from the policy.

I and several colleagues conducted an even more thorough analysis in a 2019 study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics. We examined the effects of 138 state-level minimum wage increases from 1979 to 2016 in the United States. Comparing states that increased their minimum wages with states that did not, we found the change in employment (in the five years after the change occurred) took place in a narrow band around the new minimum wage: Understandably, jobs paying below the minimum decreased -- since wages rose. But at least as many jobs were added at the new, higher wage -- meaning jobs were upgraded, not destroyed. All told, the number of low wage jobs barely budged. This finding held when we looked at populations of special concern -- people with fewer educational credentials, for instance, or young workers. The finding held, as well, even when the minimum wage was set at a fairly high rate compared with the state's median wage (the highest being around 60 percent of the median wage). We found no effect on employment at levels significantly above the minimum wage.

We also explained why some other studies arrived at different (and, we think, less accurate) conclusions. Some, for instance, didn't account for regional booms and busts. When cities are economically thriving, wages get bid up, which can be misinterpreted as a drop in low-wage jobs. At the same time, the high cost of living in some booming cities can lead low-wage workers not to move there in the first place. One study that skeptics of the minimum wage like to cite, for example, conducted by researchers at the University of Washington, examined the effect of an increase in the minimum wage in Seattle from $9.47 per hour to as much as $11 in 2015 -- and then to as much as $13 in 2016. They found the second wage increase reduced hours worked in low-wage jobs by around 9 percent, while wages increased by about 3 percent -- for a net loss in the typical low-wage employees' earnings of about $125 per month. That's a big deal -- if true.

But that analysis didn't sufficiently take into account Seattle's status as an outlier "superstar" city, one where factors beside the minimum wage shape wages on the low end, in the ways described above. In fact, in a follow-up study, the same researchers, using a different methodology, found something much more in line with the consensus. In that analysis, they found the wage increase "brought benefits to many workers employed at the time, while leaving few employed workers worse off," as a New York Times summary of that paper put it.

In another study out this month, my co-author Attila Lindner and I built on our previous paper and studied the impact of 21 citywide minimum wages in places like Seattle, Los Angeles and Chicago. On average, the minimum wages in these cities were around 63 percent of the median, sometimes stretching up to 80 percent. Comparing those cities with others that had not raised the minimum wage, we found they saw stronger wage growth at the bottom than similar cities that did not raise the minimum. In a pattern that should be sounding familiar by now, after the minimum wage increase, there were fewer jobs paying right below the new minimum -- balanced by a roughly equal increase in jobs paying at or right above it. The wage increase essentially did not affect the overall number of jobs.

So how could the CBO come to the conclusion it did? For one thing, its report examines only 11 studies; these overlap with, but are not as comprehensive as, those I reviewed for the British Treasury report. (Tellingly, its sources include the first University of Washington study but not the follow-up that came to a more positive conclusion.) The CBO also changed its formula for summarizing the literature since the last time it looked at this question (in 2019). Back then, it looked at the median result of the 11 papers; this time, it placed more weight on those that found large job losses. The 2019 report was already somewhat out of step with the latest academic research, but the new one is even more so. It concludes that a 10 percent increase in average wages of affected workers would lead to a 4.8 percent fall in employment -- far above what I and others have found. That's how it arrives at the figure of 1.4 million lost jobs. Based on my own review of the overall evidence but still following CBO's approach, I would estimate that a national minimum wage increase to $15 per hour would lead to job losses under 500,000.

No doubt, moving to a $15 per hour minimum wage by 2025 would be a major policy change. As with any such change, it is important to acknowledge uncertainty and avoid overconfident projections. Is it possible that we may see more job losses from this policy than we have in the past? Yes. However, high-quality studies that have looked at the impact in low-wage, high-impact areas have yet to detect sharper job losses even when the minimum wage is close to 80 percent of the local area median income. (A $15 minimum by 2024 would probably produce a wage at around 80 percent of the median wage in a state like West Virginia, though it would exceed that level in some parts of the state.) At the same time, the risks of keeping the minimum wage too low -- in terms of increased poverty, inequality and racial injustice -- should be taken into account. Overall, the weight of the evidence suggests a $15 minimum wage would improve the lives of millions of American families.

Opponents of raising the minimum wage have seized on a recent report by the Congressional Budget Office that estimated that increasing it to $15 an hour by 2025 would cause 1.4 million Americans to lose their jobs. These "significant job losses," according to a U.S. Chamber of Commerce vice president, provide reason enough to abandon the Biden administration's plan to help low-income workers.

First, it important to recognize the CBO also observes that income gains resulting from the wage increase are substantially greater than the reduction in income from job losses, thereby lifting nearly a million people out of poverty. Nonetheless, the report's assumptions about job losses are problematic -- significantly out of step with modern research on the subject.

A recent survey of the evidence in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, for instance, by the labor economist Alan Manning, carried an apt title that captures scholars' views far better: "The Elusive Employment Effects of Minimum Wages." Obviously, there is some point at which a high minimum wage would reduce employment, Manning explained, but the past few decades of research suggest "the currently observed range of minimum wages apparently does not include the turning-point." (Note that several states already are on paths toward a $15-per-hour minimum.)

I have also conducted multiple studies and reviews of the minimum-wage literature and agree that effects on employment are elusive. In 2019, for example, I was asked to undertake a review of minimum-wage scholarship for the British Treasury by the Conservative Party chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond. I concluded the weight of the evidence points to a fairly small impact of higher minimum wages on employment, even as they significantly increase the earnings of low paid workers.

What does "fairly small" mean, in this context? I looked at 55 different academic studies of episodes where a minimum wage was introduced or raised -- 36 in the United States, 11 in other developed countries. I found that for the typical study in the middle of the range of demonstrated effects, when average pay of affected workers rises by 10 percent after a mandated wage increase, their employment falls by at most 2 percent. But the studies that found job losses of that scale large tended to focus on narrow groups of affected workers (often teens or young adults) -- who may be particularly affected. When I focused on studies that looked at overall low-wage workforce, the evidence on job losses were minute: In those cases, the job loss from the same 10 percent increase in average wage of affected workers amounts to maybe 0.5 percent. At that level of job loss, the wage gains far offset the losses: The low-wage workforce as a whole is better off from the policy.

I and several colleagues conducted an even more thorough analysis in a 2019 study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics. We examined the effects of 138 state-level minimum wage increases from 1979 to 2016 in the United States. Comparing states that increased their minimum wages with states that did not, we found the change in employment (in the five years after the change occurred) took place in a narrow band around the new minimum wage: Understandably, jobs paying below the minimum decreased -- since wages rose. But at least as many jobs were added at the new, higher wage -- meaning jobs were upgraded, not destroyed. All told, the number of low wage jobs barely budged. This finding held when we looked at populations of special concern -- people with fewer educational credentials, for instance, or young workers. The finding held, as well, even when the minimum wage was set at a fairly high rate compared with the state's median wage (the highest being around 60 percent of the median wage). We found no effect on employment at levels significantly above the minimum wage.

We also explained why some other studies arrived at different (and, we think, less accurate) conclusions. Some, for instance, didn't account for regional booms and busts. When cities are economically thriving, wages get bid up, which can be misinterpreted as a drop in low-wage jobs. At the same time, the high cost of living in some booming cities can lead low-wage workers not to move there in the first place. One study that skeptics of the minimum wage like to cite, for example, conducted by researchers at the University of Washington, examined the effect of an increase in the minimum wage in Seattle from $9.47 per hour to as much as $11 in 2015 -- and then to as much as $13 in 2016. They found the second wage increase reduced hours worked in low-wage jobs by around 9 percent, while wages increased by about 3 percent -- for a net loss in the typical low-wage employees' earnings of about $125 per month. That's a big deal -- if true.

But that analysis didn't sufficiently take into account Seattle's status as an outlier "superstar" city, one where factors beside the minimum wage shape wages on the low end, in the ways described above. In fact, in a follow-up study, the same researchers, using a different methodology, found something much more in line with the consensus. In that analysis, they found the wage increase "brought benefits to many workers employed at the time, while leaving few employed workers worse off," as a New York Times summary of that paper put it.

In another study out this month, my co-author Attila Lindner and I built on our previous paper and studied the impact of 21 citywide minimum wages in places like Seattle, Los Angeles and Chicago. On average, the minimum wages in these cities were around 63 percent of the median, sometimes stretching up to 80 percent. Comparing those cities with others that had not raised the minimum wage, we found they saw stronger wage growth at the bottom than similar cities that did not raise the minimum. In a pattern that should be sounding familiar by now, after the minimum wage increase, there were fewer jobs paying right below the new minimum -- balanced by a roughly equal increase in jobs paying at or right above it. The wage increase essentially did not affect the overall number of jobs.

So how could the CBO come to the conclusion it did? For one thing, its report examines only 11 studies; these overlap with, but are not as comprehensive as, those I reviewed for the British Treasury report. (Tellingly, its sources include the first University of Washington study but not the follow-up that came to a more positive conclusion.) The CBO also changed its formula for summarizing the literature since the last time it looked at this question (in 2019). Back then, it looked at the median result of the 11 papers; this time, it placed more weight on those that found large job losses. The 2019 report was already somewhat out of step with the latest academic research, but the new one is even more so. It concludes that a 10 percent increase in average wages of affected workers would lead to a 4.8 percent fall in employment -- far above what I and others have found. That's how it arrives at the figure of 1.4 million lost jobs. Based on my own review of the overall evidence but still following CBO's approach, I would estimate that a national minimum wage increase to $15 per hour would lead to job losses under 500,000.

No doubt, moving to a $15 per hour minimum wage by 2025 would be a major policy change. As with any such change, it is important to acknowledge uncertainty and avoid overconfident projections. Is it possible that we may see more job losses from this policy than we have in the past? Yes. However, high-quality studies that have looked at the impact in low-wage, high-impact areas have yet to detect sharper job losses even when the minimum wage is close to 80 percent of the local area median income. (A $15 minimum by 2024 would probably produce a wage at around 80 percent of the median wage in a state like West Virginia, though it would exceed that level in some parts of the state.) At the same time, the risks of keeping the minimum wage too low -- in terms of increased poverty, inequality and racial injustice -- should be taken into account. Overall, the weight of the evidence suggests a $15 minimum wage would improve the lives of millions of American families.