SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Travelers at the Atlanta airport wearing facemasks during the coronavirus crisis. (Photo: Chad Davis)

If you're like, well, much of the population of the planet right now, you're doing little other than obsessively reading news sites for the latest on the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus, maybe taking an occasional break to check whether you're really developing a dry cough or just imagining it. Between coverage of Italian quarantine riots and stranded cruise ships, and the latest Trump fictions, there's plenty to absorb anyone's attention, even without the added distraction of concern over the health of yourself and your loved ones.

Unfortunately, because this is the corporate-controlled, understaffed, underexperienced news media we're talking about, much of that coverage has been incomplete, misleading or sometimes just plain wrong. Reading up on the new coronavirus can feel like a rabbit hole of conflicting reports: Is COVID-19 an unprecedented new threat, or just the equivalent of a really bad flu? Is closing schools a pointless danger to students in need of school lunches, and one that could risk spreading the virus farther and keeping needed healthcare workers at home to care for children, or a measure that was proven to work during the 1918 flu epidemic? And amid the rushed coverage of an evolving news story, attempts to paint a full picture that cross-references all that has been learned about the virus and how to fight it have been few and far between.

Fortunately, there are a few tricks that can make the miasma of coronavirus coverage easier to fight through. Some of these are just good media literacy, while some are more specific to keeping sane during public health scares in particular.

Don't worry too much about the ever-changing numbers. Much of the coronavirus coverage has focused on the one set of facts that seem incontrovertible: how many people have been infected, and how many have died as a result of the disease (ABC News, 3/6/20; New York Times, 3/8/20; Reuters, 3/8/20).

But even what appear to be simple numbers can be misleading in the case of a rapidly developing outbreak. The death rate from COVID-19 has bounced around from 2% (Washington Post, 2/22/20), to between 0.1% and 3% (New York Times, 2/28/20), to 3.4% (New York Times, 2/29/20). (The mortality rate from seasonal flu viruses, by comparison, averages around 0.1%.)

That's in part because the numbers continue to evolve as the virus spreads, but also because calculating an accurate death rate is "PhD-level hard," according to BBC News (3/4/20). Most of the death rate coverage did not specify what these figures were percentages of: A 2% mortality rate, for example, is far scarier if it's the percentage of all those infected (including many people who may develop few or no symptoms) than if it's a percentage solely of those who require hospitalization. Most mild cases are never reported to medical officials, and different nations with different levels of medical care -- and healthcare professionals who are more or less overwhelmed by a quick rise in cases -- will see wildly varying numbers of fatalities. (Writing in Slate--3/4/20--Boston emergency physician Jeremy Samuel Faust noted that initial death-rate estimates in the 2009 H1N1 epidemic were as much as ten times higher than the eventually determined rate.)

At the same time, numbers for total infections -- as seen on widely disseminated maps of the spread of the virus (New York Times, NBC News, Washington Post) -- are worthless without knowing how many people in those nations have been tested. An article in the Atlantic (3/9/20) noted that the US could only confirm having tested 4,384 people for COVID-19, when at an equivalent stage in its outbreak, South Korea had tested more than 100,000; Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch told the magazine that journalists should stop referring to US reports of infections as "new cases," and instead "should refer to them as 'newly discovered cases,' in order to remove the impression that the number of cases reported has any bearing on the actual number."

Even otherwise informative articles can fall victim to this kind of mathematical shorthand. An unusually useful article in Bloomberg News (3/8/20) on what makes coronavirus symptoms severe for some patients and not for others -- "danger starts," it cautions, when an infection advances beyond the nose and throat and reaches the lungs -- briskly stated that "one in seven patients develops difficulty breathing and other severe complications, while 6% become critical." But that's out of "laboratory-confirmed patients" in China, according to the WHO study (2/16-24/20) that first reported these numbers, which is likely to be skewed toward more serious cases, since those with mild cases are less commonly subjected to testing.

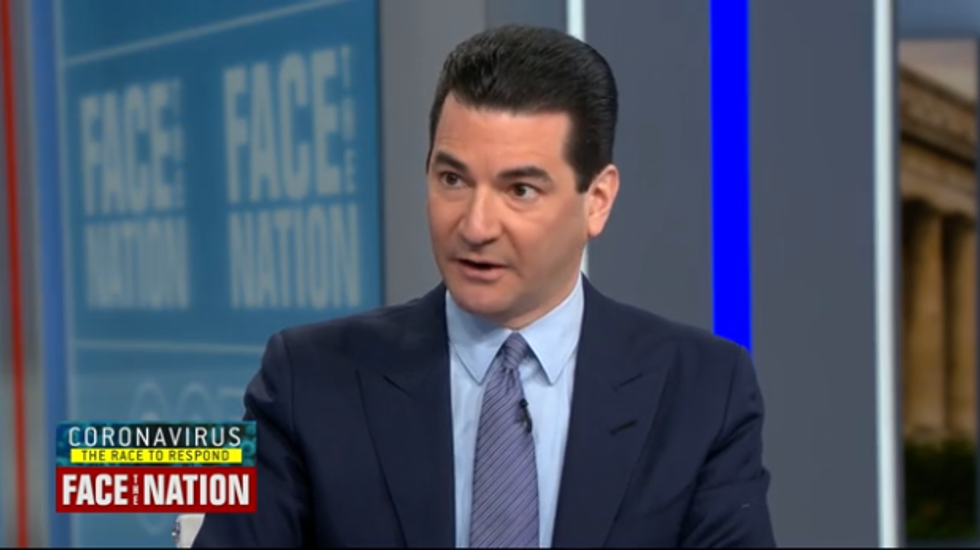

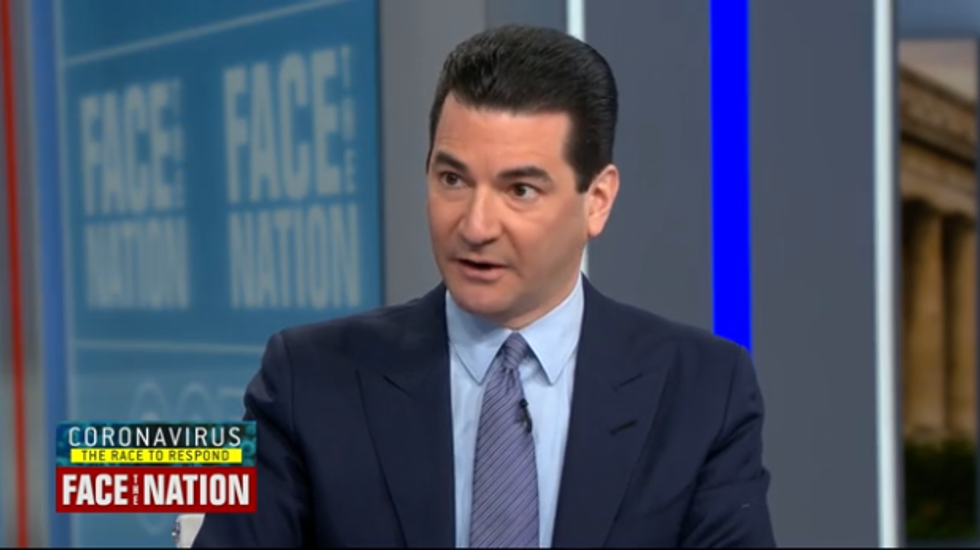

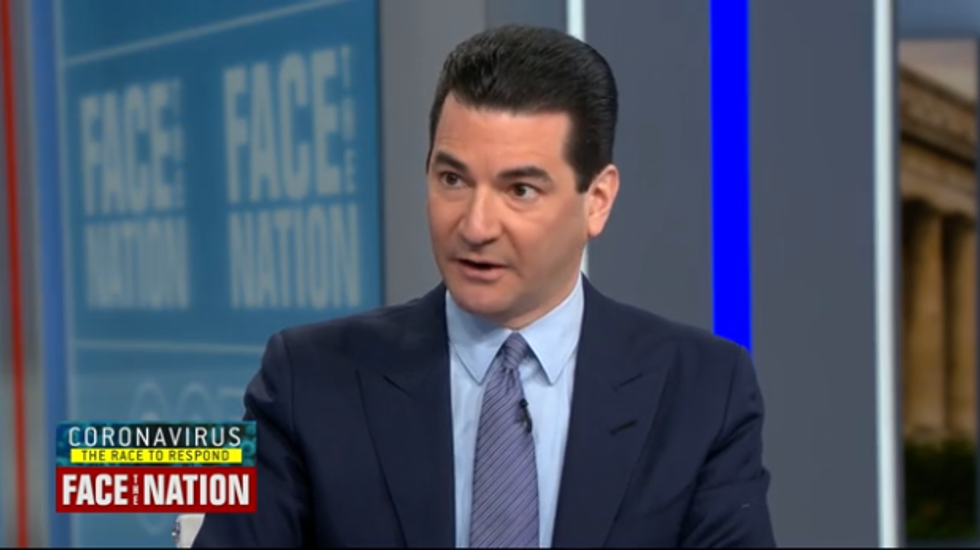

Learn the difference between "containment" and "mitigation": These terms entered widespread media use after former Trump FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb told Face the Nation (CBS, 3/8/20): "We're past the point of containment. We have to implement broad mitigation strategies." As some news reports noted (LA Times, 3/8/20), this meant moving to broader societal measures like closing schools, canceling large public events and having more employees work from home.

But what news coverage didn't always get across was that this was not just a response to a worsening epidemic, but a distinctly separate phase of addressing any disease outbreak: When only a relative handful of people have gotten infected, it's still possible to try to isolate them and prevent spread of the disease to the broader population. Once microbes are at large in much of a community, however, the best approach is to practice what epidemiologists call "social distancing": reducing contacts between as many people as possible, in order to keep a disease from spreading like wildfire.

Importantly, containment and mitigation have very different aims. The former is about targeting specific populations (say, people who have arrived recently from China or Italy) and keeping them away from the general public as much as possible, to keep more people from being exposed. Mitigation, however, is less about keeping people from getting sick than about keeping them from getting sick all at once.

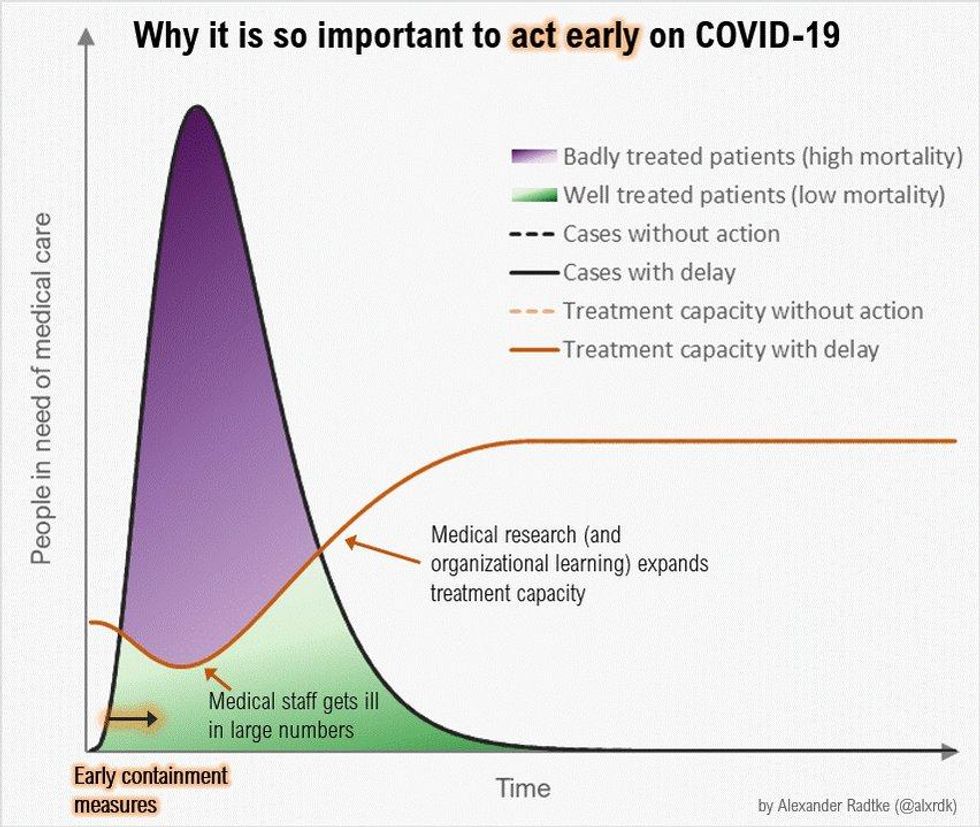

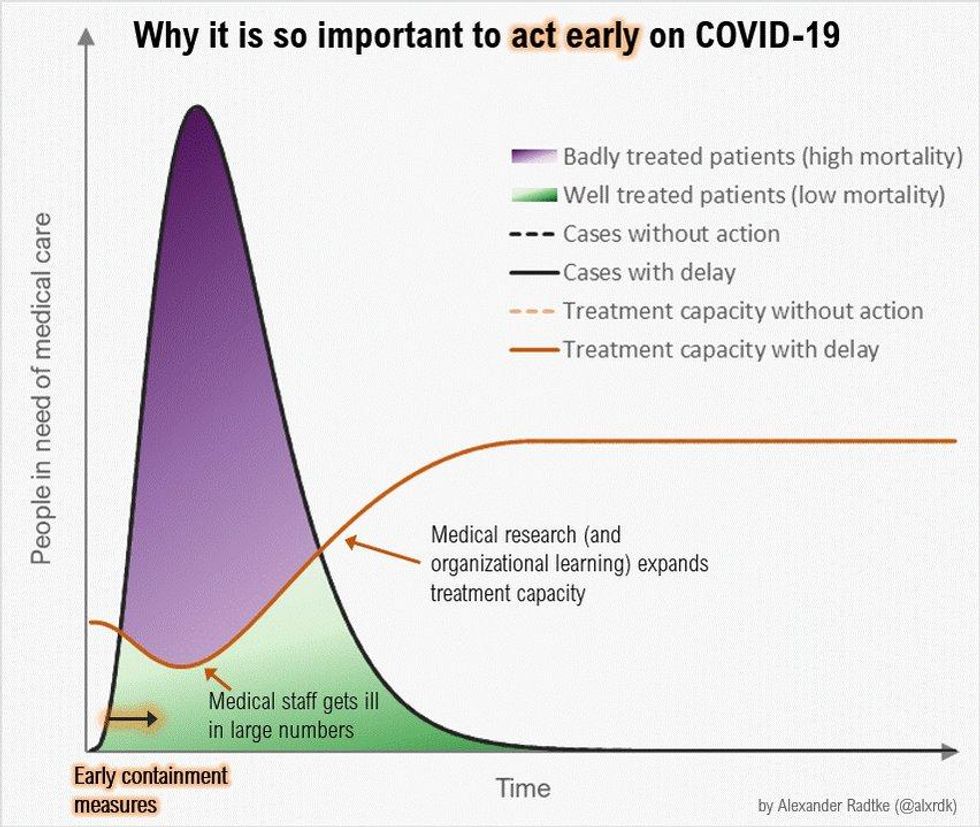

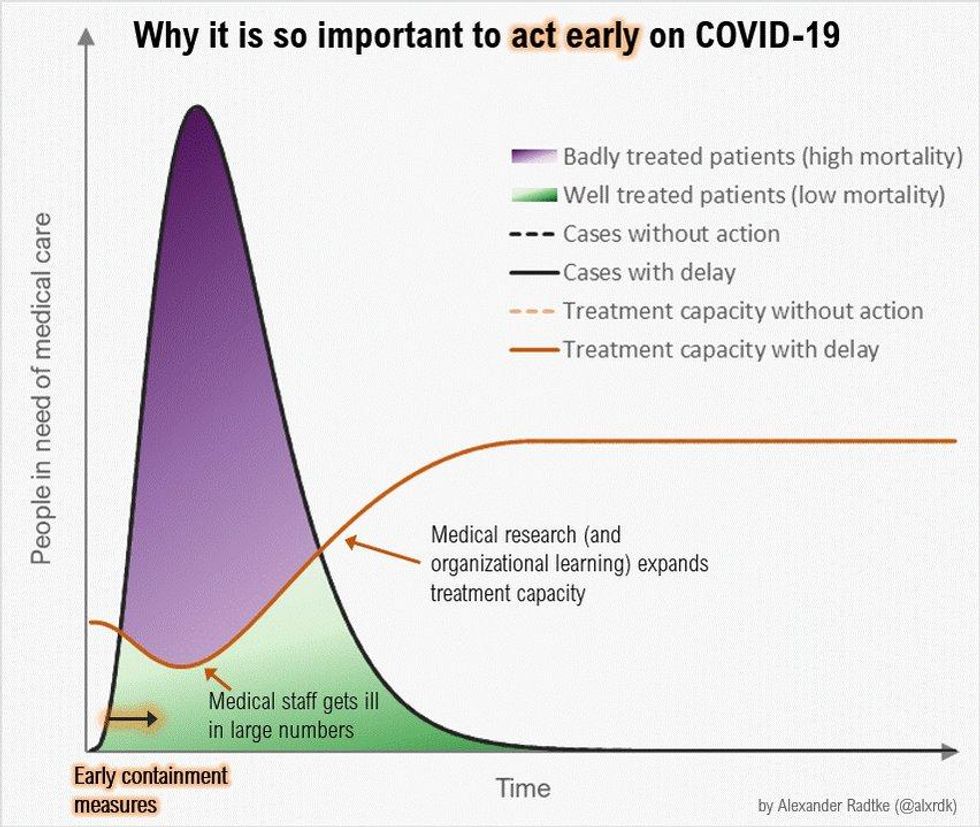

The best illustration of this remains the "Flatten the Curve" graph, first made by Rosamund Pearce of the Economist and turned into an animation by German engineer Alexander Radtke. Mitigation measures are put in place when it's all but certain that the majority of a population will eventually be infected, a tipping point some experts believe we may inevitably reach (CBS News, 3/2/20). At that point, the goal is to slow the infection rate so that hospitals and other medical treatment facilities don't get overwhelmed -- something can help bring down the fatality rate significantly.

The media coverage, however, hasn't always gotten this message across clearly. The New York Times (3/8/20), for example, ran an article with the potentially misleading headline "US Health Experts Say Stricter Measures Are Required to Limit Coronavirus's Spread," though the experts cited actually called for a switch from containment to mitigation measures. The Times described this as "telling people in affected areas not to go out" -- but in fact, under containment, some people (those who may have had contact with infected people, or who have high risk factors) are already being told to remain home. Even more confusingly, the second half of the article focused on quarantining those on infected cruise ships or nursing homes, which are containment measures, not mitigation.

Understand the likely timeline of an outbreak. School closures so far have mostly been for a matter of days (Atlantic, 3/8/20) or weeks (New York, 3/6/20); meanwhile, Gottlieb's statement that "we're looking at two months probably of difficulty" was widely cited in news reports.

Some of this has to do with uncertainty over the spread of the coronavirus: The number of cases ramped up quickly in parts of China and Italy, and no one is sure how quickly it will die down. But, also, looking at this as a crisis that will soon pass may end up being the wrong approach.

Disease experts have been predicting for weeks now (Business Insider, 2/28/20) that the arrival of warmer weather could help -- many viruses survive longer in cold, dry weather, and staying indoors reduces immune response and keeps more people breathing recirculated air -- though we won't know for sure until we see whether this virus behaves like others (CNBC, 3/6/20). But even if COVID-19 does wane in the summer, it will likely return and spread more rapidly again in the fall and become another endemic seasonal infection, like the flu. This isn't necessarily a disaster -- vaccines and other treatments could eventually be developed, meaning all other things being equal, it's better to fall sick later than sooner -- but it also means that any and all predictions of when things will return to normal should be taken with a grain of salt.

Read firsthand reports from nations where the virus has already hit. Many of the US media reports on Italy's expansion of travel and event restrictions on March 9 (CNN, 3/9/20; Washington Post, 3/9/20) described it as a "lockdown," conflating containment measures (such as travel restrictions) and social distancing ones (such as limits on public events), without ever clearly explaining precisely what rules had been put in place. (CNN asserted that Italian officials would use "thermoscan appliances" to enforce rail travel bans, implying that Italians would only be prohibited from traveling if they had a fever; the Washington Post explained that no one was permitted to travel except for "essential work, health reasons or other emergencies.")

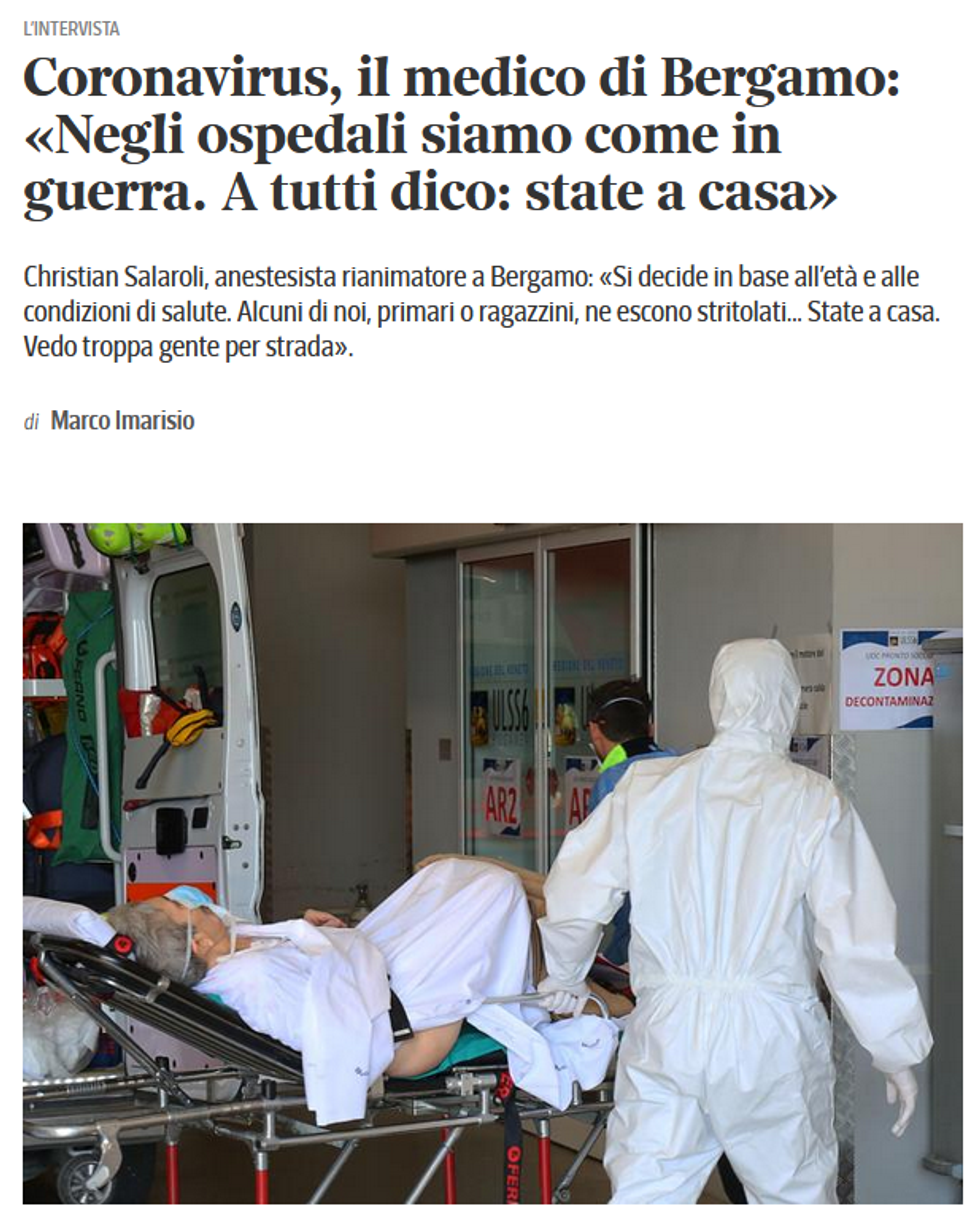

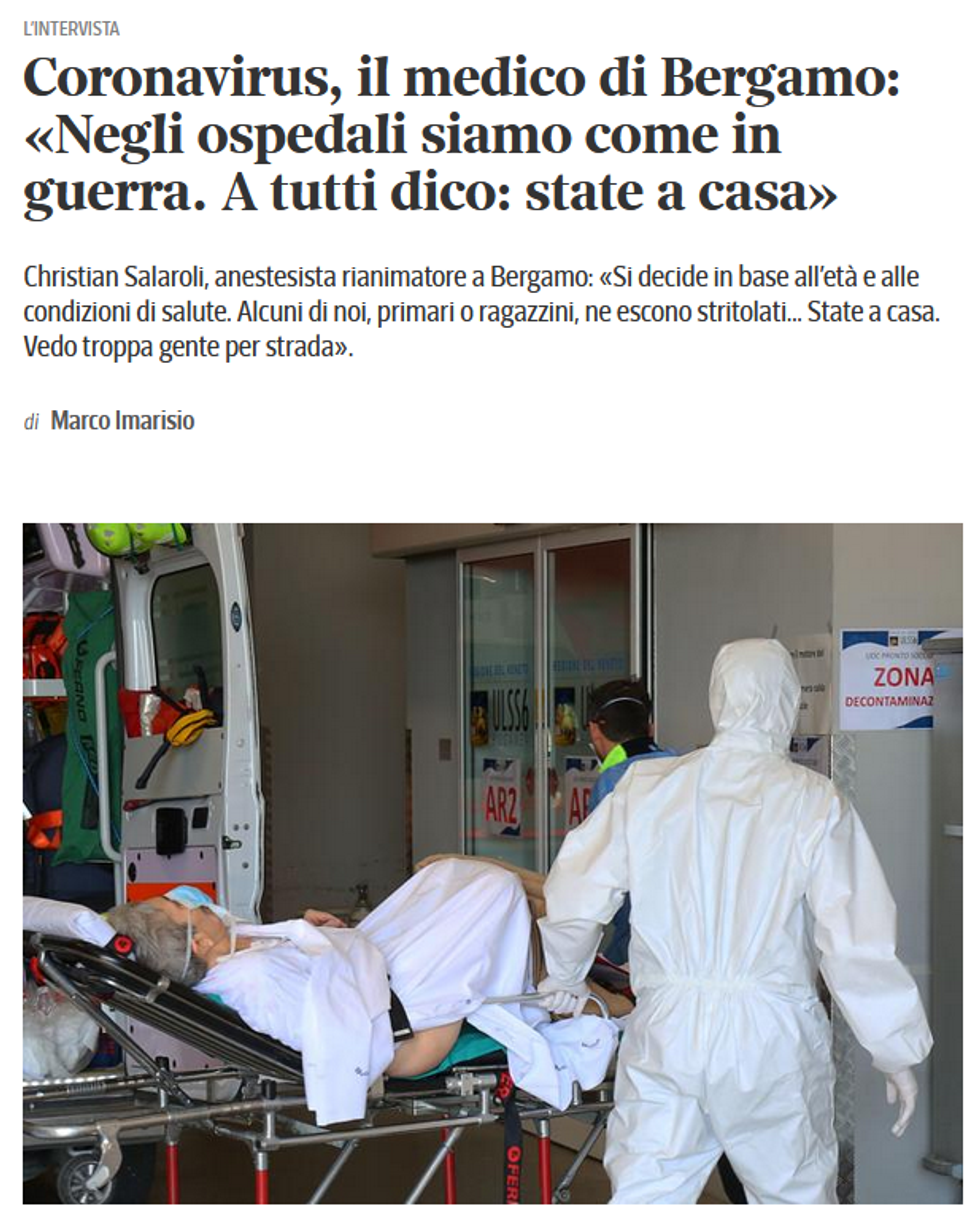

Meanwhile, Daniele Macchini, an ICU doctor in Bergamo, Lombardy, wrote a long Facebook post, later translated into English and posted to Twitter by a colleague, describing an "epidemiological disaster" where 15 to 20 mostly elderly new patients arrive every day, overwhelming staff and facilities alike:

Every ventilator becomes like gold: those in operating theatres that have now suspended their non-urgent activity become intensive care places that did not exist before.

Added Christian Salaroli, medical director of a Bergamo hospital, told the Milan newspaper Corriere Della Sera (3/9/20) that

if a person between 80 and 95 has severe respiratory failure, you probably won't proceed. If he has a multi-organic failure of more than three vital organs, it means he has a 100% mortality rate. He is now gone.

For those still healthy, meanwhile, European English-language newspaper The Local (3/9/20) reported that stores and restaurants were open, but for limited hours and with limits on how many people could enter, to keep shoppers and diners at least six feet apart, the distance considered necessary to prevent easy transmission of the virus; newspapers also printed the self-certification form (Il Messaggero, 3/9/20) that Italians can print out and present to officials to indicate that they need permission to travel.

Ask the questions that the media coverage is not. When it's reported that the CDC has directed older adults and those with "severe chronic medical conditions" to stay home as much as possible and avoid crowds when going out (CNN, 3/6/20), what kind of conditions are included, and what age groups? (The CDC release specifically warned those with "heart disease, diabetes or lung disease," and didn't outline an age cutoff, though other studies have shown that the death rate begins to spike above age 50, as noted in Talking Points Memo, 3/7/20.) If you're supposed to stay home when sick with COVID-19, does that mean you should avoid going out even to be tested? (As one opinion writer in the New York Times--3/9/20--found out, even health professionals aren't yet sure about that one.) Why has northern Italy seen such a high hospitalization and death rate when it has advanced medical facilities? (No one is exactly certain, but one theory is that it has to do with Italy having the largest proportion of residents over age 65 -- 22.6% -- of any European nation, as reported in The Local--3/5/20.)

And if all else fails, follow John Oliver's rule of thumb on Last Week Tonight (3/1/20):

It's really about trying to strike a sensible balance. Basically, if you're drinking bleach to protect yourself right now, you should probably calm the fuck down. If you're, say, licking subway poles because you're certain nothing can hurt you, maybe don't do that. You want to stay somewhere between those extremes. Don't be complacent, and don't be a fucking idiot.

Words to live by, whether you're a reader trying to understand a growing epidemic, or just a news reporter or editor trying to cover one.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

If you're like, well, much of the population of the planet right now, you're doing little other than obsessively reading news sites for the latest on the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus, maybe taking an occasional break to check whether you're really developing a dry cough or just imagining it. Between coverage of Italian quarantine riots and stranded cruise ships, and the latest Trump fictions, there's plenty to absorb anyone's attention, even without the added distraction of concern over the health of yourself and your loved ones.

Unfortunately, because this is the corporate-controlled, understaffed, underexperienced news media we're talking about, much of that coverage has been incomplete, misleading or sometimes just plain wrong. Reading up on the new coronavirus can feel like a rabbit hole of conflicting reports: Is COVID-19 an unprecedented new threat, or just the equivalent of a really bad flu? Is closing schools a pointless danger to students in need of school lunches, and one that could risk spreading the virus farther and keeping needed healthcare workers at home to care for children, or a measure that was proven to work during the 1918 flu epidemic? And amid the rushed coverage of an evolving news story, attempts to paint a full picture that cross-references all that has been learned about the virus and how to fight it have been few and far between.

Fortunately, there are a few tricks that can make the miasma of coronavirus coverage easier to fight through. Some of these are just good media literacy, while some are more specific to keeping sane during public health scares in particular.

Don't worry too much about the ever-changing numbers. Much of the coronavirus coverage has focused on the one set of facts that seem incontrovertible: how many people have been infected, and how many have died as a result of the disease (ABC News, 3/6/20; New York Times, 3/8/20; Reuters, 3/8/20).

But even what appear to be simple numbers can be misleading in the case of a rapidly developing outbreak. The death rate from COVID-19 has bounced around from 2% (Washington Post, 2/22/20), to between 0.1% and 3% (New York Times, 2/28/20), to 3.4% (New York Times, 2/29/20). (The mortality rate from seasonal flu viruses, by comparison, averages around 0.1%.)

That's in part because the numbers continue to evolve as the virus spreads, but also because calculating an accurate death rate is "PhD-level hard," according to BBC News (3/4/20). Most of the death rate coverage did not specify what these figures were percentages of: A 2% mortality rate, for example, is far scarier if it's the percentage of all those infected (including many people who may develop few or no symptoms) than if it's a percentage solely of those who require hospitalization. Most mild cases are never reported to medical officials, and different nations with different levels of medical care -- and healthcare professionals who are more or less overwhelmed by a quick rise in cases -- will see wildly varying numbers of fatalities. (Writing in Slate--3/4/20--Boston emergency physician Jeremy Samuel Faust noted that initial death-rate estimates in the 2009 H1N1 epidemic were as much as ten times higher than the eventually determined rate.)

At the same time, numbers for total infections -- as seen on widely disseminated maps of the spread of the virus (New York Times, NBC News, Washington Post) -- are worthless without knowing how many people in those nations have been tested. An article in the Atlantic (3/9/20) noted that the US could only confirm having tested 4,384 people for COVID-19, when at an equivalent stage in its outbreak, South Korea had tested more than 100,000; Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch told the magazine that journalists should stop referring to US reports of infections as "new cases," and instead "should refer to them as 'newly discovered cases,' in order to remove the impression that the number of cases reported has any bearing on the actual number."

Even otherwise informative articles can fall victim to this kind of mathematical shorthand. An unusually useful article in Bloomberg News (3/8/20) on what makes coronavirus symptoms severe for some patients and not for others -- "danger starts," it cautions, when an infection advances beyond the nose and throat and reaches the lungs -- briskly stated that "one in seven patients develops difficulty breathing and other severe complications, while 6% become critical." But that's out of "laboratory-confirmed patients" in China, according to the WHO study (2/16-24/20) that first reported these numbers, which is likely to be skewed toward more serious cases, since those with mild cases are less commonly subjected to testing.

Learn the difference between "containment" and "mitigation": These terms entered widespread media use after former Trump FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb told Face the Nation (CBS, 3/8/20): "We're past the point of containment. We have to implement broad mitigation strategies." As some news reports noted (LA Times, 3/8/20), this meant moving to broader societal measures like closing schools, canceling large public events and having more employees work from home.

But what news coverage didn't always get across was that this was not just a response to a worsening epidemic, but a distinctly separate phase of addressing any disease outbreak: When only a relative handful of people have gotten infected, it's still possible to try to isolate them and prevent spread of the disease to the broader population. Once microbes are at large in much of a community, however, the best approach is to practice what epidemiologists call "social distancing": reducing contacts between as many people as possible, in order to keep a disease from spreading like wildfire.

Importantly, containment and mitigation have very different aims. The former is about targeting specific populations (say, people who have arrived recently from China or Italy) and keeping them away from the general public as much as possible, to keep more people from being exposed. Mitigation, however, is less about keeping people from getting sick than about keeping them from getting sick all at once.

The best illustration of this remains the "Flatten the Curve" graph, first made by Rosamund Pearce of the Economist and turned into an animation by German engineer Alexander Radtke. Mitigation measures are put in place when it's all but certain that the majority of a population will eventually be infected, a tipping point some experts believe we may inevitably reach (CBS News, 3/2/20). At that point, the goal is to slow the infection rate so that hospitals and other medical treatment facilities don't get overwhelmed -- something can help bring down the fatality rate significantly.

The media coverage, however, hasn't always gotten this message across clearly. The New York Times (3/8/20), for example, ran an article with the potentially misleading headline "US Health Experts Say Stricter Measures Are Required to Limit Coronavirus's Spread," though the experts cited actually called for a switch from containment to mitigation measures. The Times described this as "telling people in affected areas not to go out" -- but in fact, under containment, some people (those who may have had contact with infected people, or who have high risk factors) are already being told to remain home. Even more confusingly, the second half of the article focused on quarantining those on infected cruise ships or nursing homes, which are containment measures, not mitigation.

Understand the likely timeline of an outbreak. School closures so far have mostly been for a matter of days (Atlantic, 3/8/20) or weeks (New York, 3/6/20); meanwhile, Gottlieb's statement that "we're looking at two months probably of difficulty" was widely cited in news reports.

Some of this has to do with uncertainty over the spread of the coronavirus: The number of cases ramped up quickly in parts of China and Italy, and no one is sure how quickly it will die down. But, also, looking at this as a crisis that will soon pass may end up being the wrong approach.

Disease experts have been predicting for weeks now (Business Insider, 2/28/20) that the arrival of warmer weather could help -- many viruses survive longer in cold, dry weather, and staying indoors reduces immune response and keeps more people breathing recirculated air -- though we won't know for sure until we see whether this virus behaves like others (CNBC, 3/6/20). But even if COVID-19 does wane in the summer, it will likely return and spread more rapidly again in the fall and become another endemic seasonal infection, like the flu. This isn't necessarily a disaster -- vaccines and other treatments could eventually be developed, meaning all other things being equal, it's better to fall sick later than sooner -- but it also means that any and all predictions of when things will return to normal should be taken with a grain of salt.

Read firsthand reports from nations where the virus has already hit. Many of the US media reports on Italy's expansion of travel and event restrictions on March 9 (CNN, 3/9/20; Washington Post, 3/9/20) described it as a "lockdown," conflating containment measures (such as travel restrictions) and social distancing ones (such as limits on public events), without ever clearly explaining precisely what rules had been put in place. (CNN asserted that Italian officials would use "thermoscan appliances" to enforce rail travel bans, implying that Italians would only be prohibited from traveling if they had a fever; the Washington Post explained that no one was permitted to travel except for "essential work, health reasons or other emergencies.")

Meanwhile, Daniele Macchini, an ICU doctor in Bergamo, Lombardy, wrote a long Facebook post, later translated into English and posted to Twitter by a colleague, describing an "epidemiological disaster" where 15 to 20 mostly elderly new patients arrive every day, overwhelming staff and facilities alike:

Every ventilator becomes like gold: those in operating theatres that have now suspended their non-urgent activity become intensive care places that did not exist before.

Added Christian Salaroli, medical director of a Bergamo hospital, told the Milan newspaper Corriere Della Sera (3/9/20) that

if a person between 80 and 95 has severe respiratory failure, you probably won't proceed. If he has a multi-organic failure of more than three vital organs, it means he has a 100% mortality rate. He is now gone.

For those still healthy, meanwhile, European English-language newspaper The Local (3/9/20) reported that stores and restaurants were open, but for limited hours and with limits on how many people could enter, to keep shoppers and diners at least six feet apart, the distance considered necessary to prevent easy transmission of the virus; newspapers also printed the self-certification form (Il Messaggero, 3/9/20) that Italians can print out and present to officials to indicate that they need permission to travel.

Ask the questions that the media coverage is not. When it's reported that the CDC has directed older adults and those with "severe chronic medical conditions" to stay home as much as possible and avoid crowds when going out (CNN, 3/6/20), what kind of conditions are included, and what age groups? (The CDC release specifically warned those with "heart disease, diabetes or lung disease," and didn't outline an age cutoff, though other studies have shown that the death rate begins to spike above age 50, as noted in Talking Points Memo, 3/7/20.) If you're supposed to stay home when sick with COVID-19, does that mean you should avoid going out even to be tested? (As one opinion writer in the New York Times--3/9/20--found out, even health professionals aren't yet sure about that one.) Why has northern Italy seen such a high hospitalization and death rate when it has advanced medical facilities? (No one is exactly certain, but one theory is that it has to do with Italy having the largest proportion of residents over age 65 -- 22.6% -- of any European nation, as reported in The Local--3/5/20.)

And if all else fails, follow John Oliver's rule of thumb on Last Week Tonight (3/1/20):

It's really about trying to strike a sensible balance. Basically, if you're drinking bleach to protect yourself right now, you should probably calm the fuck down. If you're, say, licking subway poles because you're certain nothing can hurt you, maybe don't do that. You want to stay somewhere between those extremes. Don't be complacent, and don't be a fucking idiot.

Words to live by, whether you're a reader trying to understand a growing epidemic, or just a news reporter or editor trying to cover one.

If you're like, well, much of the population of the planet right now, you're doing little other than obsessively reading news sites for the latest on the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus, maybe taking an occasional break to check whether you're really developing a dry cough or just imagining it. Between coverage of Italian quarantine riots and stranded cruise ships, and the latest Trump fictions, there's plenty to absorb anyone's attention, even without the added distraction of concern over the health of yourself and your loved ones.

Unfortunately, because this is the corporate-controlled, understaffed, underexperienced news media we're talking about, much of that coverage has been incomplete, misleading or sometimes just plain wrong. Reading up on the new coronavirus can feel like a rabbit hole of conflicting reports: Is COVID-19 an unprecedented new threat, or just the equivalent of a really bad flu? Is closing schools a pointless danger to students in need of school lunches, and one that could risk spreading the virus farther and keeping needed healthcare workers at home to care for children, or a measure that was proven to work during the 1918 flu epidemic? And amid the rushed coverage of an evolving news story, attempts to paint a full picture that cross-references all that has been learned about the virus and how to fight it have been few and far between.

Fortunately, there are a few tricks that can make the miasma of coronavirus coverage easier to fight through. Some of these are just good media literacy, while some are more specific to keeping sane during public health scares in particular.

Don't worry too much about the ever-changing numbers. Much of the coronavirus coverage has focused on the one set of facts that seem incontrovertible: how many people have been infected, and how many have died as a result of the disease (ABC News, 3/6/20; New York Times, 3/8/20; Reuters, 3/8/20).

But even what appear to be simple numbers can be misleading in the case of a rapidly developing outbreak. The death rate from COVID-19 has bounced around from 2% (Washington Post, 2/22/20), to between 0.1% and 3% (New York Times, 2/28/20), to 3.4% (New York Times, 2/29/20). (The mortality rate from seasonal flu viruses, by comparison, averages around 0.1%.)

That's in part because the numbers continue to evolve as the virus spreads, but also because calculating an accurate death rate is "PhD-level hard," according to BBC News (3/4/20). Most of the death rate coverage did not specify what these figures were percentages of: A 2% mortality rate, for example, is far scarier if it's the percentage of all those infected (including many people who may develop few or no symptoms) than if it's a percentage solely of those who require hospitalization. Most mild cases are never reported to medical officials, and different nations with different levels of medical care -- and healthcare professionals who are more or less overwhelmed by a quick rise in cases -- will see wildly varying numbers of fatalities. (Writing in Slate--3/4/20--Boston emergency physician Jeremy Samuel Faust noted that initial death-rate estimates in the 2009 H1N1 epidemic were as much as ten times higher than the eventually determined rate.)

At the same time, numbers for total infections -- as seen on widely disseminated maps of the spread of the virus (New York Times, NBC News, Washington Post) -- are worthless without knowing how many people in those nations have been tested. An article in the Atlantic (3/9/20) noted that the US could only confirm having tested 4,384 people for COVID-19, when at an equivalent stage in its outbreak, South Korea had tested more than 100,000; Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch told the magazine that journalists should stop referring to US reports of infections as "new cases," and instead "should refer to them as 'newly discovered cases,' in order to remove the impression that the number of cases reported has any bearing on the actual number."

Even otherwise informative articles can fall victim to this kind of mathematical shorthand. An unusually useful article in Bloomberg News (3/8/20) on what makes coronavirus symptoms severe for some patients and not for others -- "danger starts," it cautions, when an infection advances beyond the nose and throat and reaches the lungs -- briskly stated that "one in seven patients develops difficulty breathing and other severe complications, while 6% become critical." But that's out of "laboratory-confirmed patients" in China, according to the WHO study (2/16-24/20) that first reported these numbers, which is likely to be skewed toward more serious cases, since those with mild cases are less commonly subjected to testing.

Learn the difference between "containment" and "mitigation": These terms entered widespread media use after former Trump FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb told Face the Nation (CBS, 3/8/20): "We're past the point of containment. We have to implement broad mitigation strategies." As some news reports noted (LA Times, 3/8/20), this meant moving to broader societal measures like closing schools, canceling large public events and having more employees work from home.

But what news coverage didn't always get across was that this was not just a response to a worsening epidemic, but a distinctly separate phase of addressing any disease outbreak: When only a relative handful of people have gotten infected, it's still possible to try to isolate them and prevent spread of the disease to the broader population. Once microbes are at large in much of a community, however, the best approach is to practice what epidemiologists call "social distancing": reducing contacts between as many people as possible, in order to keep a disease from spreading like wildfire.

Importantly, containment and mitigation have very different aims. The former is about targeting specific populations (say, people who have arrived recently from China or Italy) and keeping them away from the general public as much as possible, to keep more people from being exposed. Mitigation, however, is less about keeping people from getting sick than about keeping them from getting sick all at once.

The best illustration of this remains the "Flatten the Curve" graph, first made by Rosamund Pearce of the Economist and turned into an animation by German engineer Alexander Radtke. Mitigation measures are put in place when it's all but certain that the majority of a population will eventually be infected, a tipping point some experts believe we may inevitably reach (CBS News, 3/2/20). At that point, the goal is to slow the infection rate so that hospitals and other medical treatment facilities don't get overwhelmed -- something can help bring down the fatality rate significantly.

The media coverage, however, hasn't always gotten this message across clearly. The New York Times (3/8/20), for example, ran an article with the potentially misleading headline "US Health Experts Say Stricter Measures Are Required to Limit Coronavirus's Spread," though the experts cited actually called for a switch from containment to mitigation measures. The Times described this as "telling people in affected areas not to go out" -- but in fact, under containment, some people (those who may have had contact with infected people, or who have high risk factors) are already being told to remain home. Even more confusingly, the second half of the article focused on quarantining those on infected cruise ships or nursing homes, which are containment measures, not mitigation.

Understand the likely timeline of an outbreak. School closures so far have mostly been for a matter of days (Atlantic, 3/8/20) or weeks (New York, 3/6/20); meanwhile, Gottlieb's statement that "we're looking at two months probably of difficulty" was widely cited in news reports.

Some of this has to do with uncertainty over the spread of the coronavirus: The number of cases ramped up quickly in parts of China and Italy, and no one is sure how quickly it will die down. But, also, looking at this as a crisis that will soon pass may end up being the wrong approach.

Disease experts have been predicting for weeks now (Business Insider, 2/28/20) that the arrival of warmer weather could help -- many viruses survive longer in cold, dry weather, and staying indoors reduces immune response and keeps more people breathing recirculated air -- though we won't know for sure until we see whether this virus behaves like others (CNBC, 3/6/20). But even if COVID-19 does wane in the summer, it will likely return and spread more rapidly again in the fall and become another endemic seasonal infection, like the flu. This isn't necessarily a disaster -- vaccines and other treatments could eventually be developed, meaning all other things being equal, it's better to fall sick later than sooner -- but it also means that any and all predictions of when things will return to normal should be taken with a grain of salt.

Read firsthand reports from nations where the virus has already hit. Many of the US media reports on Italy's expansion of travel and event restrictions on March 9 (CNN, 3/9/20; Washington Post, 3/9/20) described it as a "lockdown," conflating containment measures (such as travel restrictions) and social distancing ones (such as limits on public events), without ever clearly explaining precisely what rules had been put in place. (CNN asserted that Italian officials would use "thermoscan appliances" to enforce rail travel bans, implying that Italians would only be prohibited from traveling if they had a fever; the Washington Post explained that no one was permitted to travel except for "essential work, health reasons or other emergencies.")

Meanwhile, Daniele Macchini, an ICU doctor in Bergamo, Lombardy, wrote a long Facebook post, later translated into English and posted to Twitter by a colleague, describing an "epidemiological disaster" where 15 to 20 mostly elderly new patients arrive every day, overwhelming staff and facilities alike:

Every ventilator becomes like gold: those in operating theatres that have now suspended their non-urgent activity become intensive care places that did not exist before.

Added Christian Salaroli, medical director of a Bergamo hospital, told the Milan newspaper Corriere Della Sera (3/9/20) that

if a person between 80 and 95 has severe respiratory failure, you probably won't proceed. If he has a multi-organic failure of more than three vital organs, it means he has a 100% mortality rate. He is now gone.

For those still healthy, meanwhile, European English-language newspaper The Local (3/9/20) reported that stores and restaurants were open, but for limited hours and with limits on how many people could enter, to keep shoppers and diners at least six feet apart, the distance considered necessary to prevent easy transmission of the virus; newspapers also printed the self-certification form (Il Messaggero, 3/9/20) that Italians can print out and present to officials to indicate that they need permission to travel.

Ask the questions that the media coverage is not. When it's reported that the CDC has directed older adults and those with "severe chronic medical conditions" to stay home as much as possible and avoid crowds when going out (CNN, 3/6/20), what kind of conditions are included, and what age groups? (The CDC release specifically warned those with "heart disease, diabetes or lung disease," and didn't outline an age cutoff, though other studies have shown that the death rate begins to spike above age 50, as noted in Talking Points Memo, 3/7/20.) If you're supposed to stay home when sick with COVID-19, does that mean you should avoid going out even to be tested? (As one opinion writer in the New York Times--3/9/20--found out, even health professionals aren't yet sure about that one.) Why has northern Italy seen such a high hospitalization and death rate when it has advanced medical facilities? (No one is exactly certain, but one theory is that it has to do with Italy having the largest proportion of residents over age 65 -- 22.6% -- of any European nation, as reported in The Local--3/5/20.)

And if all else fails, follow John Oliver's rule of thumb on Last Week Tonight (3/1/20):

It's really about trying to strike a sensible balance. Basically, if you're drinking bleach to protect yourself right now, you should probably calm the fuck down. If you're, say, licking subway poles because you're certain nothing can hurt you, maybe don't do that. You want to stay somewhere between those extremes. Don't be complacent, and don't be a fucking idiot.

Words to live by, whether you're a reader trying to understand a growing epidemic, or just a news reporter or editor trying to cover one.