SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

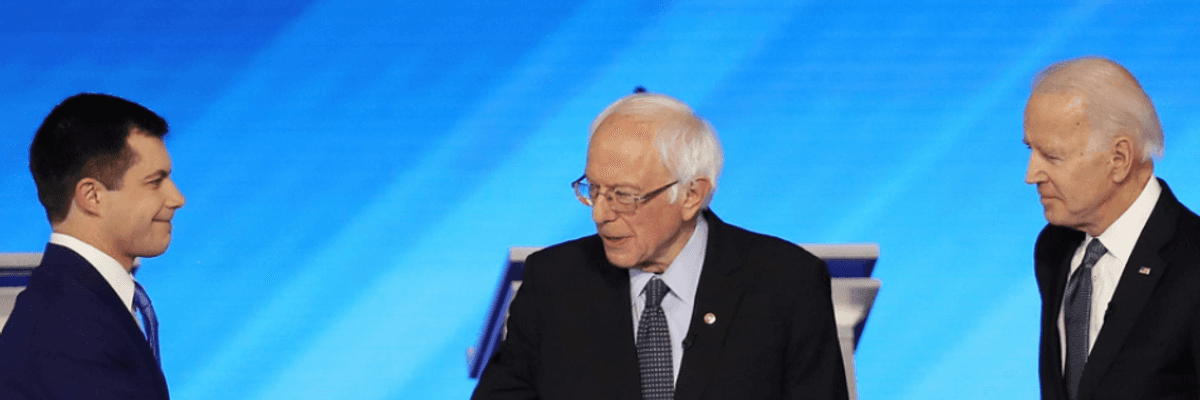

Democratic presidential candidates former South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and former Vice President Joe Biden greet each other prior to the start of the Democratic presidential primary debate in the Sullivan Arena at St. Anselm College on February 07, 2020 in Manchester, New Hampshire. (Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

One of the most frustrating things for me, as a political writer over the last twenty-five years, was the inability of most liberals to grasp what neoliberalism was. But compared to even five years ago, the situation has changed dramatically, as many more ordinary people--nurses, teachers, salespeople, accountants, drivers--understand what the ideology signifies. They are rapidly moving away from the false Republican-Democrat dichotomy, or the identity politics prism which blurs the true nature of neoliberal inequality and focusing on the true nature of power.

Bernie Sanders calls it the reign of the "billionaire class." He constantly enumerates the dominant corporate industries that have a stranglehold on American politics. He talks about the 1% who are scared of political revolution. He's right. Neoliberalism is what happened to both the Democrats and the Republicans when they agreed to put into practice, starting from the 1970s onwards, certain radical ideas about human social organization that had been percolating since the end of World War II.

Both Democrats and Republicans agree on the basic consensus, with only slight variations on emphasis. Thus it is futile to expect any improvements for working people with the preferred candidates of either party, because both are equally dedicated to preserving extreme corporate domination and the annihilation of freedom and dignity for those who do not have such power.

Neoliberalism has tried to bring about a fundamental reorientation of human psychology. We might say that the "meritocrats" it likes to cheer so enthusiastically are the embodiment of this psychological transformation. Citizens have been indoctrinated to think of themselves as independent profit centers, as everyone looks out for themselves. Any shared sacrifice for the common good is demeaned as idealistic or utopian--even basic decencies such as a living wage or inexpensive college education or health care that doesn't bankrupt you.

At the policy level, deregulation, privatization, and fiscal austerity, kicked into high gear since the Carter presidency, have meant that functions that should remain public have been turned over to private entities, the idea of universal welfare goes out the door and is replaced by earned benefits, and everyone finds themselves at the mercy of unchecked corporations that have no loyalty to class, community, or culture.

But after nearly 50 years of monopoly on political discourse, both left and right in America erupted in open rebellion in 2015. We are now witnessing the second act of this movement, in the form of the Sanders ascendancy which seeks to return the Democratic party to its participatory roots.

What encourages me so much is the resistance of ordinary voters to the kinds of hoodwinking that used to be more fatalistically accepted in earlier times.

When Pete Buttigieg suggests that people can keep their private health insurance and choose Medicare if they want it, voters understand that this is neoliberal subterfuge for a false choice: nobody wants to pay high deductibles and premiums, instead of guaranteed care, even if Mayor Pete wants you to be scared by the trillions of extra dollars he thinks it will cost. In fact, universal government programs are always cheaper and fairer than private alternatives, even if neoliberalism, particularly under Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, successfully propagated the contrary myth. Buttigieg's recent advocacy of mandatory public service and his anxiety about deficit spending align with the perennial neoliberal themes of discipline and austerity.

When Elizabeth Warren hesitates to endorse a Medicare for All program that immediately starts making the transition from the patchwork Obamacare, voters understand that this is right out of the playbook of making us settle for half a loaf by creating the impression that swallowing a full loaf will cause indigestion. In fact, what is administratively and psychologically difficult to manage is a quintessential neoliberal program like Obamacare, with legions of exceptions, qualifications, and exclusions.

Most of the early entrants in the Democratic nomination race, like Kamala Harris, Julian Castro, and Cory Booker, who at first endorsed Medicare for All but backed off when pressed for details or timelines, paid the price in voter disapproval. Amy Klobuchar is yet to undergo her trial by fire on this issue, but as she continues advancing in the polls, it will come soon enough. To base your whole candidacy on standing pat, because nothing is legislatively possible, even if this fatalism is cloaked in folksy Midwestern pragmatism, is exactly the kind of subservience to unchecked corporate power that has voters disillusioned.

Joe Biden's career encapsulates the transition of a Democrat who came to power after the end of Lyndon Johnson's war on poverty and the idealism of the 1960s, and who smoothly transitioned to an overt neoliberal disciplinary stance, reflected in his vigorous advocacy of the war on drugs, mass incarceration, civil liberties abridgment, and tougher bankruptcy exemptions. That subtle white supremacy easily shades over into an economic repression that cuts across all races is something much better understood than just a few years ago, when the Clintons were expertly propagandized as natural allies of African Americans.

Not long ago, identity politics would have canceled the clarity that has resulted from the focus on neoliberal inequality. Voters don't seem interested in voting for Warren or Harris as a woman per se, if they see their policies as hurting all people, including women. The same dynamic applies to Buttigieg, whose gay identity is not the overruling factor as was blackness in the case of Barack Obama; rather, whether Buttigieg's neoliberal accommodation actually hurts all people, including people in the LGBTQ community, seems to be the overriding consideration--as it should be.

The cover of meritocracy--which simply means that the aspirant successfully met neoliberalism's criteria for professional competition--is increasingly of little value in electoral politics. Buttigieg is almost the paradigmatic case, with his Harvard education, Rhodes scholarship, voluntary military intelligence service, McKinsey apprenticeship, and mayoral governance derived from the vacuous public language Bill Clinton and Barack Obama perfected. Yet Buttigieg will rise and fall on whether he can deviate from such neoliberal verities as adding a public option to Obamacare or relying on cap-and-trade to deal with climate change.

Bernie Sanders's greatest service has been to insist on his "democratic socialist" moniker, even when many insisted he should opt for the safer "social democrat." I always approved of his choice, because the disrupting label initiated a thought process that now seems to have reached a critical mass. If Sanders is a democratic socialist, then what exactly are Warren, Buttigieg, and Biden? How far removed are they from FDR and LBJ's domestic vision? That's the kind of vital discussion ordinary people all over the country are engaging in, even if the academic elites are lagging far behind. But they'll come around yet, once working people show them the way in mastering the hidden language of power.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

One of the most frustrating things for me, as a political writer over the last twenty-five years, was the inability of most liberals to grasp what neoliberalism was. But compared to even five years ago, the situation has changed dramatically, as many more ordinary people--nurses, teachers, salespeople, accountants, drivers--understand what the ideology signifies. They are rapidly moving away from the false Republican-Democrat dichotomy, or the identity politics prism which blurs the true nature of neoliberal inequality and focusing on the true nature of power.

Bernie Sanders calls it the reign of the "billionaire class." He constantly enumerates the dominant corporate industries that have a stranglehold on American politics. He talks about the 1% who are scared of political revolution. He's right. Neoliberalism is what happened to both the Democrats and the Republicans when they agreed to put into practice, starting from the 1970s onwards, certain radical ideas about human social organization that had been percolating since the end of World War II.

Both Democrats and Republicans agree on the basic consensus, with only slight variations on emphasis. Thus it is futile to expect any improvements for working people with the preferred candidates of either party, because both are equally dedicated to preserving extreme corporate domination and the annihilation of freedom and dignity for those who do not have such power.

Neoliberalism has tried to bring about a fundamental reorientation of human psychology. We might say that the "meritocrats" it likes to cheer so enthusiastically are the embodiment of this psychological transformation. Citizens have been indoctrinated to think of themselves as independent profit centers, as everyone looks out for themselves. Any shared sacrifice for the common good is demeaned as idealistic or utopian--even basic decencies such as a living wage or inexpensive college education or health care that doesn't bankrupt you.

At the policy level, deregulation, privatization, and fiscal austerity, kicked into high gear since the Carter presidency, have meant that functions that should remain public have been turned over to private entities, the idea of universal welfare goes out the door and is replaced by earned benefits, and everyone finds themselves at the mercy of unchecked corporations that have no loyalty to class, community, or culture.

But after nearly 50 years of monopoly on political discourse, both left and right in America erupted in open rebellion in 2015. We are now witnessing the second act of this movement, in the form of the Sanders ascendancy which seeks to return the Democratic party to its participatory roots.

What encourages me so much is the resistance of ordinary voters to the kinds of hoodwinking that used to be more fatalistically accepted in earlier times.

When Pete Buttigieg suggests that people can keep their private health insurance and choose Medicare if they want it, voters understand that this is neoliberal subterfuge for a false choice: nobody wants to pay high deductibles and premiums, instead of guaranteed care, even if Mayor Pete wants you to be scared by the trillions of extra dollars he thinks it will cost. In fact, universal government programs are always cheaper and fairer than private alternatives, even if neoliberalism, particularly under Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, successfully propagated the contrary myth. Buttigieg's recent advocacy of mandatory public service and his anxiety about deficit spending align with the perennial neoliberal themes of discipline and austerity.

When Elizabeth Warren hesitates to endorse a Medicare for All program that immediately starts making the transition from the patchwork Obamacare, voters understand that this is right out of the playbook of making us settle for half a loaf by creating the impression that swallowing a full loaf will cause indigestion. In fact, what is administratively and psychologically difficult to manage is a quintessential neoliberal program like Obamacare, with legions of exceptions, qualifications, and exclusions.

Most of the early entrants in the Democratic nomination race, like Kamala Harris, Julian Castro, and Cory Booker, who at first endorsed Medicare for All but backed off when pressed for details or timelines, paid the price in voter disapproval. Amy Klobuchar is yet to undergo her trial by fire on this issue, but as she continues advancing in the polls, it will come soon enough. To base your whole candidacy on standing pat, because nothing is legislatively possible, even if this fatalism is cloaked in folksy Midwestern pragmatism, is exactly the kind of subservience to unchecked corporate power that has voters disillusioned.

Joe Biden's career encapsulates the transition of a Democrat who came to power after the end of Lyndon Johnson's war on poverty and the idealism of the 1960s, and who smoothly transitioned to an overt neoliberal disciplinary stance, reflected in his vigorous advocacy of the war on drugs, mass incarceration, civil liberties abridgment, and tougher bankruptcy exemptions. That subtle white supremacy easily shades over into an economic repression that cuts across all races is something much better understood than just a few years ago, when the Clintons were expertly propagandized as natural allies of African Americans.

Not long ago, identity politics would have canceled the clarity that has resulted from the focus on neoliberal inequality. Voters don't seem interested in voting for Warren or Harris as a woman per se, if they see their policies as hurting all people, including women. The same dynamic applies to Buttigieg, whose gay identity is not the overruling factor as was blackness in the case of Barack Obama; rather, whether Buttigieg's neoliberal accommodation actually hurts all people, including people in the LGBTQ community, seems to be the overriding consideration--as it should be.

The cover of meritocracy--which simply means that the aspirant successfully met neoliberalism's criteria for professional competition--is increasingly of little value in electoral politics. Buttigieg is almost the paradigmatic case, with his Harvard education, Rhodes scholarship, voluntary military intelligence service, McKinsey apprenticeship, and mayoral governance derived from the vacuous public language Bill Clinton and Barack Obama perfected. Yet Buttigieg will rise and fall on whether he can deviate from such neoliberal verities as adding a public option to Obamacare or relying on cap-and-trade to deal with climate change.

Bernie Sanders's greatest service has been to insist on his "democratic socialist" moniker, even when many insisted he should opt for the safer "social democrat." I always approved of his choice, because the disrupting label initiated a thought process that now seems to have reached a critical mass. If Sanders is a democratic socialist, then what exactly are Warren, Buttigieg, and Biden? How far removed are they from FDR and LBJ's domestic vision? That's the kind of vital discussion ordinary people all over the country are engaging in, even if the academic elites are lagging far behind. But they'll come around yet, once working people show them the way in mastering the hidden language of power.

One of the most frustrating things for me, as a political writer over the last twenty-five years, was the inability of most liberals to grasp what neoliberalism was. But compared to even five years ago, the situation has changed dramatically, as many more ordinary people--nurses, teachers, salespeople, accountants, drivers--understand what the ideology signifies. They are rapidly moving away from the false Republican-Democrat dichotomy, or the identity politics prism which blurs the true nature of neoliberal inequality and focusing on the true nature of power.

Bernie Sanders calls it the reign of the "billionaire class." He constantly enumerates the dominant corporate industries that have a stranglehold on American politics. He talks about the 1% who are scared of political revolution. He's right. Neoliberalism is what happened to both the Democrats and the Republicans when they agreed to put into practice, starting from the 1970s onwards, certain radical ideas about human social organization that had been percolating since the end of World War II.

Both Democrats and Republicans agree on the basic consensus, with only slight variations on emphasis. Thus it is futile to expect any improvements for working people with the preferred candidates of either party, because both are equally dedicated to preserving extreme corporate domination and the annihilation of freedom and dignity for those who do not have such power.

Neoliberalism has tried to bring about a fundamental reorientation of human psychology. We might say that the "meritocrats" it likes to cheer so enthusiastically are the embodiment of this psychological transformation. Citizens have been indoctrinated to think of themselves as independent profit centers, as everyone looks out for themselves. Any shared sacrifice for the common good is demeaned as idealistic or utopian--even basic decencies such as a living wage or inexpensive college education or health care that doesn't bankrupt you.

At the policy level, deregulation, privatization, and fiscal austerity, kicked into high gear since the Carter presidency, have meant that functions that should remain public have been turned over to private entities, the idea of universal welfare goes out the door and is replaced by earned benefits, and everyone finds themselves at the mercy of unchecked corporations that have no loyalty to class, community, or culture.

But after nearly 50 years of monopoly on political discourse, both left and right in America erupted in open rebellion in 2015. We are now witnessing the second act of this movement, in the form of the Sanders ascendancy which seeks to return the Democratic party to its participatory roots.

What encourages me so much is the resistance of ordinary voters to the kinds of hoodwinking that used to be more fatalistically accepted in earlier times.

When Pete Buttigieg suggests that people can keep their private health insurance and choose Medicare if they want it, voters understand that this is neoliberal subterfuge for a false choice: nobody wants to pay high deductibles and premiums, instead of guaranteed care, even if Mayor Pete wants you to be scared by the trillions of extra dollars he thinks it will cost. In fact, universal government programs are always cheaper and fairer than private alternatives, even if neoliberalism, particularly under Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, successfully propagated the contrary myth. Buttigieg's recent advocacy of mandatory public service and his anxiety about deficit spending align with the perennial neoliberal themes of discipline and austerity.

When Elizabeth Warren hesitates to endorse a Medicare for All program that immediately starts making the transition from the patchwork Obamacare, voters understand that this is right out of the playbook of making us settle for half a loaf by creating the impression that swallowing a full loaf will cause indigestion. In fact, what is administratively and psychologically difficult to manage is a quintessential neoliberal program like Obamacare, with legions of exceptions, qualifications, and exclusions.

Most of the early entrants in the Democratic nomination race, like Kamala Harris, Julian Castro, and Cory Booker, who at first endorsed Medicare for All but backed off when pressed for details or timelines, paid the price in voter disapproval. Amy Klobuchar is yet to undergo her trial by fire on this issue, but as she continues advancing in the polls, it will come soon enough. To base your whole candidacy on standing pat, because nothing is legislatively possible, even if this fatalism is cloaked in folksy Midwestern pragmatism, is exactly the kind of subservience to unchecked corporate power that has voters disillusioned.

Joe Biden's career encapsulates the transition of a Democrat who came to power after the end of Lyndon Johnson's war on poverty and the idealism of the 1960s, and who smoothly transitioned to an overt neoliberal disciplinary stance, reflected in his vigorous advocacy of the war on drugs, mass incarceration, civil liberties abridgment, and tougher bankruptcy exemptions. That subtle white supremacy easily shades over into an economic repression that cuts across all races is something much better understood than just a few years ago, when the Clintons were expertly propagandized as natural allies of African Americans.

Not long ago, identity politics would have canceled the clarity that has resulted from the focus on neoliberal inequality. Voters don't seem interested in voting for Warren or Harris as a woman per se, if they see their policies as hurting all people, including women. The same dynamic applies to Buttigieg, whose gay identity is not the overruling factor as was blackness in the case of Barack Obama; rather, whether Buttigieg's neoliberal accommodation actually hurts all people, including people in the LGBTQ community, seems to be the overriding consideration--as it should be.

The cover of meritocracy--which simply means that the aspirant successfully met neoliberalism's criteria for professional competition--is increasingly of little value in electoral politics. Buttigieg is almost the paradigmatic case, with his Harvard education, Rhodes scholarship, voluntary military intelligence service, McKinsey apprenticeship, and mayoral governance derived from the vacuous public language Bill Clinton and Barack Obama perfected. Yet Buttigieg will rise and fall on whether he can deviate from such neoliberal verities as adding a public option to Obamacare or relying on cap-and-trade to deal with climate change.

Bernie Sanders's greatest service has been to insist on his "democratic socialist" moniker, even when many insisted he should opt for the safer "social democrat." I always approved of his choice, because the disrupting label initiated a thought process that now seems to have reached a critical mass. If Sanders is a democratic socialist, then what exactly are Warren, Buttigieg, and Biden? How far removed are they from FDR and LBJ's domestic vision? That's the kind of vital discussion ordinary people all over the country are engaging in, even if the academic elites are lagging far behind. But they'll come around yet, once working people show them the way in mastering the hidden language of power.