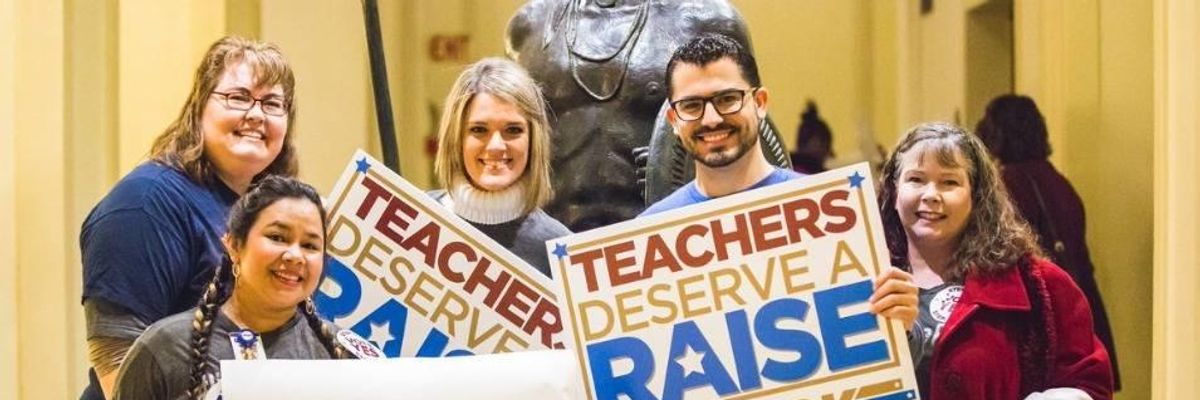

Early this year, teachers in "red" states such as West Virginia and Oklahoma walked off the job to protest declining pay and insufficient classroom resources. Shoppers at office supply stores often run into teachers with carts full of classroom supplies that their school districts say they can't afford. Last winter, Baltimore City had to close many of its schools for lack of heat, and again near the end of the year, for lack of air conditioning.

In September, a TIME magazine cover captured the nation attention; one said: " I have a master's degree, 16 years of experience, work two extra jobs and donate blood plasma to pay the bills. I'm a teacher in America."

When confronted with these issues, state and local leaders commonly throw up their hands and proclaim: "There's no money!"

In a just-published report that I co-authored, Good Jobs First examines the annual financial reports of nearly half of the nation's 13,500 school districts. We found that subsidies handed out to corporations cost school districts more than $1.8 billion last year.

The report, The New Math on School Finance, was made possible by a new accounting rule issued by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), the body that sets accounting standards used by all states and most local governments. The new rule, known as GASB Statement 77, requires state and local governments to disclose how much revenue they lose each year to tax abatements granted to corporations.

The new rule is especially important for our nation's schools. School boards are rarely given a vote when subsidies are granted and yet are usually the most impacted, since they are the costliest local public service and rely heavily on property taxes, those most commonly abated.

The losses are widespread and in some places quite large. Ten states, led by South Carolina and New York, collectively lost $1.6 billion. If these subsidies were cut and the revenue restored to hiring more teachers and reducing class size, these 10 states could collectively hire more than 28,000 new educators.

Subsidies cost 249 school districts in 22 states more than $1 million each. Four school districts--Hillsboro (in Oregon), Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), Ascension Parish (Louisiana) and St Charles Parish (Louisiana)--each lost more than $50 million to corporate tax giveaways. Hillsboro's enormous handouts, mostly to data centers owned by internet giants, cost its students $96.7 million in classroom resources.

We also found that more than half of the school districts we looked at had nothing to say about the new reporting rule. There can be legitimate reasons for this, but in most cases the new rule appears to have simply been ignored.

With this new information in hand, it's time for citizens, parents, teachers and students themselves to start asking questions. In districts that have failed to report, school board members and school business officers should be asked about the omissions. In school districts that have reported significant losses, city and county elected officials should investigate whether poorly-funded schools may be impeding economic development efforts.

Local legislators claim that tax breaks are necessary to attract business investment and create jobs. Yet the availability of a well-educated workforce is the #1 criterion when companies make investment and siting decisions. In today's tight labor market, that's especially true. In order to support sustained economic development, state legislators should consider legislation banning abatement of taxes that fund schools.

It is time for a robust reconsideration of corporate subsidies that undermine school finance.

New data made possible by the new GASB Statement 77 accounting rule provides the data to make that conversation possible.