SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

While it's heartening to see some of these high-profile offenders face consequences for their behavior, it's more than a little frustrating that it still takes such overwhelming evidence, and access to major platforms for this to occur. Many people have no such access.

Better late than never.

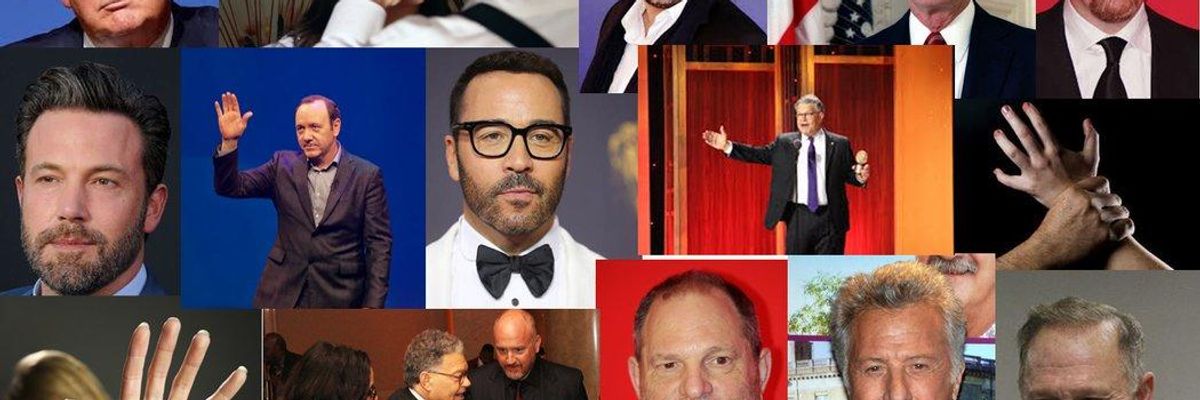

Film mogul Harvey Weinstein's case felt like a watershed moment. After decades of whispers within the Hollywood community, the high-profile movie producer's sexual misconduct was brought into the light by a scathing report by New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey. Even more amazing, a powerful man actually faced consequences for his actions, being fired from the company he helped found and being booted from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Then the dam really broke. Spurred on by the hashtag #MeToo, women (and others) began sharing stories of sexual harassment and assault. More big names were exposed for being repeat serial offenders: Louis CK, Al Franken, Kevin Spacey, Brett Ratner, and dozens more actors, producers, writers, politicians, etc. It's been called the "Weinstein Effect."

A better name might be the "We've Had Enough Effect." These examples of harassment are egregious and indicative of a much larger problem. Far too much of this kind of gross misconduct has been swept under the proverbial rug. Women have been silenced, shunned, threatened, and even killed for daring to speak up or fight back. As for the predators? They can be elected to the highest office in the land.

As a society we tend to excuse such behavior, blame the victims, and often ignore the whole thing. Look at the folks in Alabama who doggedly cling to their support of Republican Senate candidate Roy Moore even as a rising number of women accuse him of sexual misconduct or outright assault when they were just teenagers.

While it's heartening to see some of these high-profile offenders face consequences for their behavior, it's more than a little frustrating that it still takes such overwhelming evidence, and access to major platforms like the Times, for this to occur. Many people have no such access.

Young working women, women of color, indigenous women, and transgender women in particular have experienced disproportionate amounts of sexual harassment and assault.

In particular, sexual harassment is a routine experience for restaurant, agricultural, home care, and domestic workers. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives more than 12,000 allegations of sex-based harassment each year, with women accounting for about 83 percent of the complainants. And that's with only something like three out of four people experiencing workplace harassment reporting it.

Harassment on the job is so common that it is typically shrugged off as just part of the job. In a national survey of 4,300 restaurant workers by Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, more than one in ten workers reported that they or a co-worker had experienced sexual harassment. That's likely an undercount.

One focus group respondent put it succinctly: "It's inevitable. If it's not verbal assault, someone wants to rub up against you."

Activist and advocate Tarana Burke, who is black, started the Me Too movement ten years ago, but it took prominent white actresses chiming in for the mainstream culture to finally sit up and take notice.

They've been speaking about this for years. Activist and advocate Tarana Burke, who is black, started the Me Too movement ten years ago, but it took prominent white actresses chiming in for the mainstream culture to finally sit up and take notice. As Jane Fonda put it, people are listening to Weinstein's accusers because "they're famous and white."

As journalist Lin Farley noted years ago, if you're not particularly wealthy or famous, speaking out against predatory behavior is far more likely to result in losing your job and facing economic instability. If your workplace is hostile, including the HR department, there's little choice but to put up with the harassment or leave the job.

Most assaults are never reported, largely because the person targeted feels like they have more to lose by doing so than not. Reality tends to bear that out, with precious few offenders ever facing conviction or even proper jail time for their crimes, and too many victims dragged over the coals in the public square, loss of employment, lawsuits, physical threats, verbal harassment, and more. There's a nationwide backlog of rape kits that need to be tested and no real political will to fix that.

We've made it as difficult as possible for victims to seek justice.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Better late than never.

Film mogul Harvey Weinstein's case felt like a watershed moment. After decades of whispers within the Hollywood community, the high-profile movie producer's sexual misconduct was brought into the light by a scathing report by New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey. Even more amazing, a powerful man actually faced consequences for his actions, being fired from the company he helped found and being booted from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Then the dam really broke. Spurred on by the hashtag #MeToo, women (and others) began sharing stories of sexual harassment and assault. More big names were exposed for being repeat serial offenders: Louis CK, Al Franken, Kevin Spacey, Brett Ratner, and dozens more actors, producers, writers, politicians, etc. It's been called the "Weinstein Effect."

A better name might be the "We've Had Enough Effect." These examples of harassment are egregious and indicative of a much larger problem. Far too much of this kind of gross misconduct has been swept under the proverbial rug. Women have been silenced, shunned, threatened, and even killed for daring to speak up or fight back. As for the predators? They can be elected to the highest office in the land.

As a society we tend to excuse such behavior, blame the victims, and often ignore the whole thing. Look at the folks in Alabama who doggedly cling to their support of Republican Senate candidate Roy Moore even as a rising number of women accuse him of sexual misconduct or outright assault when they were just teenagers.

While it's heartening to see some of these high-profile offenders face consequences for their behavior, it's more than a little frustrating that it still takes such overwhelming evidence, and access to major platforms like the Times, for this to occur. Many people have no such access.

Young working women, women of color, indigenous women, and transgender women in particular have experienced disproportionate amounts of sexual harassment and assault.

In particular, sexual harassment is a routine experience for restaurant, agricultural, home care, and domestic workers. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives more than 12,000 allegations of sex-based harassment each year, with women accounting for about 83 percent of the complainants. And that's with only something like three out of four people experiencing workplace harassment reporting it.

Harassment on the job is so common that it is typically shrugged off as just part of the job. In a national survey of 4,300 restaurant workers by Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, more than one in ten workers reported that they or a co-worker had experienced sexual harassment. That's likely an undercount.

One focus group respondent put it succinctly: "It's inevitable. If it's not verbal assault, someone wants to rub up against you."

Activist and advocate Tarana Burke, who is black, started the Me Too movement ten years ago, but it took prominent white actresses chiming in for the mainstream culture to finally sit up and take notice.

They've been speaking about this for years. Activist and advocate Tarana Burke, who is black, started the Me Too movement ten years ago, but it took prominent white actresses chiming in for the mainstream culture to finally sit up and take notice. As Jane Fonda put it, people are listening to Weinstein's accusers because "they're famous and white."

As journalist Lin Farley noted years ago, if you're not particularly wealthy or famous, speaking out against predatory behavior is far more likely to result in losing your job and facing economic instability. If your workplace is hostile, including the HR department, there's little choice but to put up with the harassment or leave the job.

Most assaults are never reported, largely because the person targeted feels like they have more to lose by doing so than not. Reality tends to bear that out, with precious few offenders ever facing conviction or even proper jail time for their crimes, and too many victims dragged over the coals in the public square, loss of employment, lawsuits, physical threats, verbal harassment, and more. There's a nationwide backlog of rape kits that need to be tested and no real political will to fix that.

We've made it as difficult as possible for victims to seek justice.

Better late than never.

Film mogul Harvey Weinstein's case felt like a watershed moment. After decades of whispers within the Hollywood community, the high-profile movie producer's sexual misconduct was brought into the light by a scathing report by New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey. Even more amazing, a powerful man actually faced consequences for his actions, being fired from the company he helped found and being booted from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Then the dam really broke. Spurred on by the hashtag #MeToo, women (and others) began sharing stories of sexual harassment and assault. More big names were exposed for being repeat serial offenders: Louis CK, Al Franken, Kevin Spacey, Brett Ratner, and dozens more actors, producers, writers, politicians, etc. It's been called the "Weinstein Effect."

A better name might be the "We've Had Enough Effect." These examples of harassment are egregious and indicative of a much larger problem. Far too much of this kind of gross misconduct has been swept under the proverbial rug. Women have been silenced, shunned, threatened, and even killed for daring to speak up or fight back. As for the predators? They can be elected to the highest office in the land.

As a society we tend to excuse such behavior, blame the victims, and often ignore the whole thing. Look at the folks in Alabama who doggedly cling to their support of Republican Senate candidate Roy Moore even as a rising number of women accuse him of sexual misconduct or outright assault when they were just teenagers.

While it's heartening to see some of these high-profile offenders face consequences for their behavior, it's more than a little frustrating that it still takes such overwhelming evidence, and access to major platforms like the Times, for this to occur. Many people have no such access.

Young working women, women of color, indigenous women, and transgender women in particular have experienced disproportionate amounts of sexual harassment and assault.

In particular, sexual harassment is a routine experience for restaurant, agricultural, home care, and domestic workers. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives more than 12,000 allegations of sex-based harassment each year, with women accounting for about 83 percent of the complainants. And that's with only something like three out of four people experiencing workplace harassment reporting it.

Harassment on the job is so common that it is typically shrugged off as just part of the job. In a national survey of 4,300 restaurant workers by Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, more than one in ten workers reported that they or a co-worker had experienced sexual harassment. That's likely an undercount.

One focus group respondent put it succinctly: "It's inevitable. If it's not verbal assault, someone wants to rub up against you."

Activist and advocate Tarana Burke, who is black, started the Me Too movement ten years ago, but it took prominent white actresses chiming in for the mainstream culture to finally sit up and take notice.

They've been speaking about this for years. Activist and advocate Tarana Burke, who is black, started the Me Too movement ten years ago, but it took prominent white actresses chiming in for the mainstream culture to finally sit up and take notice. As Jane Fonda put it, people are listening to Weinstein's accusers because "they're famous and white."

As journalist Lin Farley noted years ago, if you're not particularly wealthy or famous, speaking out against predatory behavior is far more likely to result in losing your job and facing economic instability. If your workplace is hostile, including the HR department, there's little choice but to put up with the harassment or leave the job.

Most assaults are never reported, largely because the person targeted feels like they have more to lose by doing so than not. Reality tends to bear that out, with precious few offenders ever facing conviction or even proper jail time for their crimes, and too many victims dragged over the coals in the public square, loss of employment, lawsuits, physical threats, verbal harassment, and more. There's a nationwide backlog of rape kits that need to be tested and no real political will to fix that.

We've made it as difficult as possible for victims to seek justice.