In the most recent financial filings available, the couple who run a chain of 18 schools pay themselves $315,000 a year, plus nearly $39,000 in benefits. The school also employs their daughters, their son, and even a sister living in the Czech Republic.

Families who enroll their children in the schools are asked to contribute at least $1,500 a year per child to the school to fund its teacher bonus program. They also must pay a $300 security deposit, purchase some books, and pay for school activities that would normally be provided free at a public school.

The school chain contracts its operations to a management company, also owned by the same couple. In the most recent financial accounting available, the management firm received $4,711,699 for leased employee costs and $1,766,000 for management. Nearly $60 million total was charged to the management corporation to provide services to the schools.

After 2009, the owners made a legal change that made it possible to hide from the public much of the school's financials, including their salaries and expenses. But what we do know is that between 20012 and 2015 administrative costs of the schools were some of the highest in Arizona, where most of the schools are located, spending an average of $2,291 per pupil on administration compared to $628 per pupil spent by the average public school district in the state.

If you're having difficulty discerning whether this education operation behaves more like a for-profit or a nonprofit, you're just getting a hint of the confusing realm charter schools now occupy in the public education debate. And it's only going to get crazier.

A Split In The Bipartisan Charter Alliance

With Donald Trump's ascension to the presidency and Betsy DeVos taking over the Department of Education, charter schools have gained new momentum to expand to more communities. But that's causing problems among many charter advocates.

As education journalist Emma Brown explains in the Washington Post, the "Trump-DeVos team" has "split the bipartisan alliance that has helped vouchers and charters," as politically centrist backers of charters labor to distance themselves from the extremist politics of the new regime.

Trump's budget proposal, with its huge cuts to federal education spending and massive diversion of funds to alternatives to public schools, has widened the divide among school choice proponents, as some charter school backers have started to openly differ with people who want to expand government support for virtually all alternatives to public schools, including education management companies, virtual campuses, and taxpayer-funded vouchers for private schools.

A speech DeVos made the other day to an annual gathering of the charter school industry likely adds new fuel to the debate, as she admonished those who take a more measured, "strategic" approach to charter expansion while extolling a desire to let the floodgates of school choice open.

What this means to the average citizen is that she should expect to hear lots more rhetoric about the "good kind" of charter school versus the "not so good" kind of charter school.

The "Good Kind" Of Charter?

People are already confused about charter schools. According to the most recent survey, 58 percent of the general public say they know little or nothing about charter schools. Even people who should know better are confused.

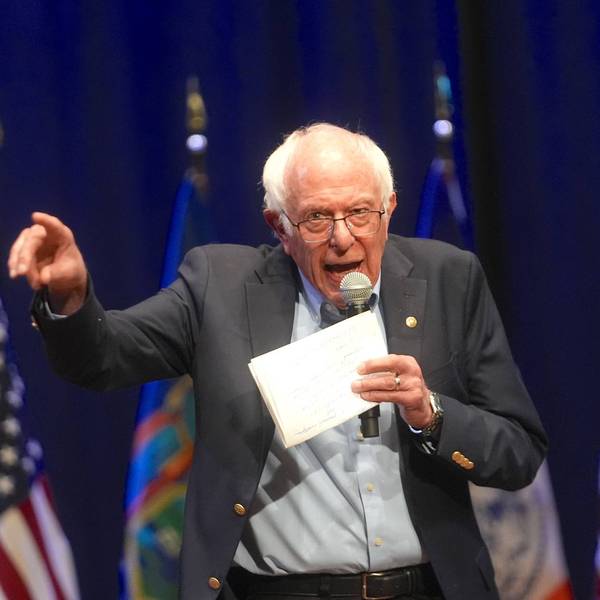

The most prominent example of this confusion was apparent in the recent presidential race, when the Democratic rival for the nomination, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, responded to a question about charter schools saying, "I believe in public charter schools. I do not believe in private [pause] privately controlled charter schools."

As I explained, technically, there is no such thing as a "private charter school," yet virtually all charter schools are "privately controlled." So it's not at all clear what Sanders meant by trying to distinguish between "public" versus "privately controlled" charters.

Another popular tactic for separating "good" charters from the pack of awfulness Trump and DeVos want to unleash is to hold a preference for "nonprofit" charter schools over the profit-making variety.

As education journalist Matt Barnum explains in the national Chalkbeat education news outlet, "For progressive charter advocates, keeping an arm's length from for-profit charter schools may be smart politics." Barnum points to prominent Democrats, including former education secretary John King, now president and CEO of EdTrust, and Shavar Jeffries of the charter-loving Democrats for Education Reform, who are proposing a ban on for-profit charters.

A new study released by CREDO, a Stanford-based research group, will doubtlessly add to the growing divide over the profit motive in the charter school industry. Barnum reviews the study in another Chalkbeat report and finds, "Charters operated by a nonprofit perform modestly better in both math and reading than for-profit schools."

So is it more important than ever to distinguish between nonprofit and for-profit charters in crafting public policy governing these schools?

Take that question and circle back to the one that opened this article.

Which Is Nonprofit?

If you guessed that the school in question at the beginning of this article is a for-profit charter, you're wrong. The charter described is the BASIS charter chain that was examined by public school advocate Carol Burris for the Washington Post.

Although BASIS is technically a nonprofit, and the CREDO study labels it as such, this organization operates as ruthlessly and self-serving as any profit hungry private enterprise would. Not only does BASIS generously enrich the private holdings of a select few of its inner circle executives; it also selectively serves an elite echelon of students - generally the most able-minded Asian and white students who have the stamina and familial support to survive the schools' test-obsessed culture.

But it's "nonprofit."

Here's another example of a charter school that blurs the line between profit-making vs. mission-driven schooling.

This chain of charter schools presents itself as a collection of charters operating regionally. One group operates a series of schools across the Midwest, another group operates across western states, and another is focused mostly in Texas. But the various charter operations have a lot in common, at least in their business practices.

Each charter group is closely associated with a private E-rate company, a company providing telecommunications and internet services to schools qualifying for the special discount provided by the federal government.

In the case of the Midwest branch, the E-rate provider has bid on 58 contracts representing over $3.2 million exclusively with the charter company. The E-rate firm appears to have no other clients nor any interests in acquiring new clients.

In the case of the charter operation covering Arizona, California, Nevada, and Utah, the E-rate provider is listed as a holding of one of the Arizona schools. All of its 48 E-rate bids have gone exclusively to schools operating in the charter chain.

At the charter operation in Texas, the telecommunications firm associated with the chain has 23 contracts with the related schools, which constitutes nearly all, 94 percent, of its business.

Compare that school's operation to this one.

This charter operation, a national company, forms a charter school board to "invite" itself into a community to manage a new school. The governing board is not independent of the management company, and members of the board can serve on multiple charter boards.

After securing a contract to manage the new school, the charter purchases a building - it could be a storefront in a strip mall or an abandoned warehouse - and requests approval from an authorizer to open a school there. After the authorization, the charter board signs a lease agreement with a development company to take over ownership of the building. The development company is located at the same address as the home office of the charter management firm.

Now the charter management firm and its related enterprises own the building and its contents, even if desks, computers, and equipment have been purchased with taxpayer money. It receives rent payments from the district. It owns the curriculum the school teaches. And if the charter management firm is ever fired, the charter board - and by extension the district - is in the awkward position of having to buy back its own school.

A Distinction Without A Difference

Of the three charter operations I've examined here, only the last one is technically for-profit, according to CREDO.

In addition to BASIS, the other nonprofit charter operation is the Gulen charter network, the nation's largest chain of bricks-and-mortar charters, which takes its name from the Turkish cleric Fetullah Gulen.

In an in-depth report for Jacobin, George Joseph reveals, "The Gulen charter network has developed a growth model more reminiscent of a Fortune 500 company than a public school district."

In addition to the partnering E-rate firms, Gulen schools have close business associations with school construction companies that receive millions of dollars from contracts to build and renovate Gulen schools exclusively. The foundations and public relations firms associated with the schools also spend lavishly on marketing campaigns, political campaigns, and junkets for local officials.

The for-profit charter firm I describe is National Heritage Academies, whose shady business practices I reported on in North Carolina.

But in all three cases, whether nonprofit or for-profit, charter schools, simply by the way they are structured and operate, create opportunities for all kinds of third-parties to skim off public funds without adding any education value to the system.

Does it make any difference what their tax status is?