$2.13 an Hour? Why The Tipped Minimum Wage Has to Go

The person who serves you lunch today may work for a minimum hourly wage that's less than the price of your coffee. And no matter how generous your tip, at the end of the day, she'll take home much less in wages than what she deserves.

The person who serves you lunch today may work for a minimum hourly wage that's less than the price of your coffee. And no matter how generous your tip, at the end of the day, she'll take home much less in wages than what she deserves. Federal law has been exploiting workers like her for years, according to labor advocates, thanks to an ultra-low wage floor that systematically cheats servers, bartenders, hairdressers and others of a fair day's pay.

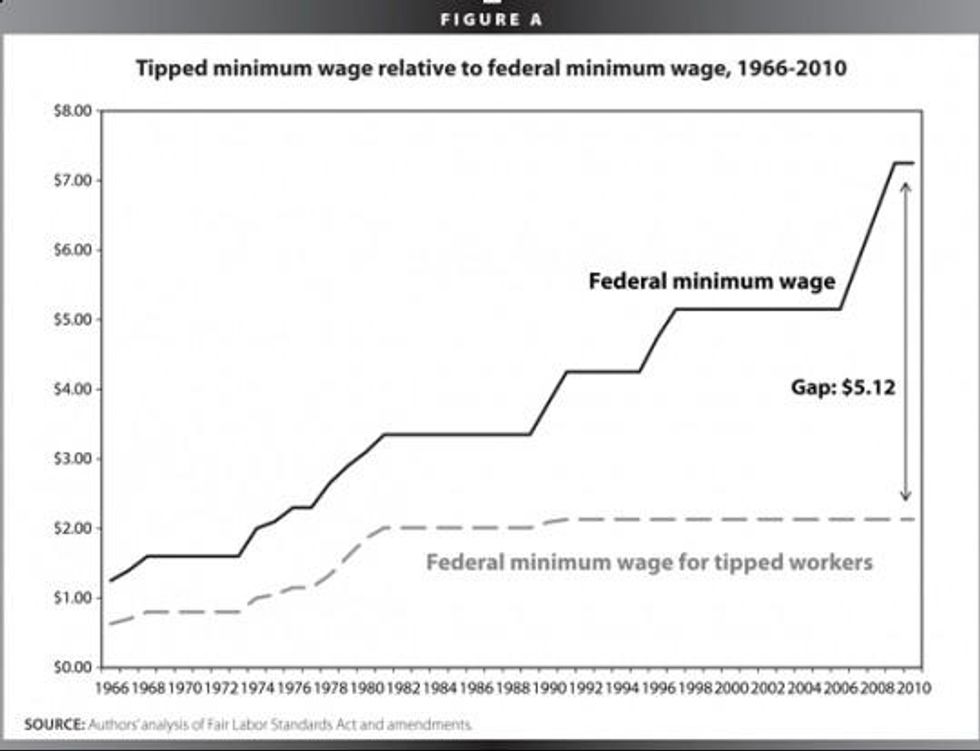

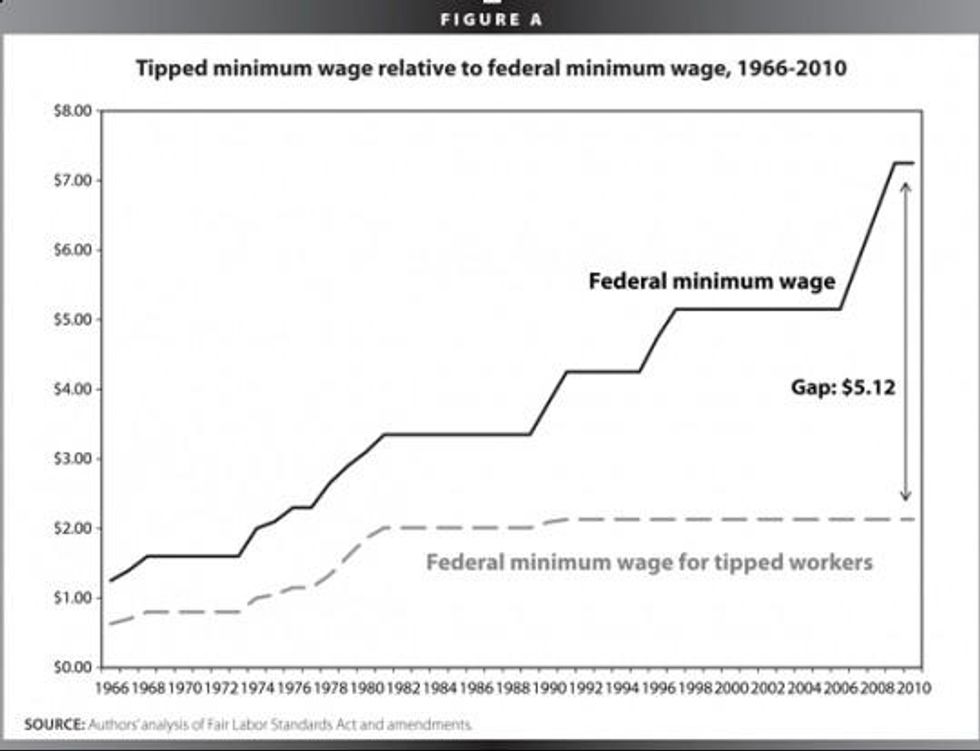

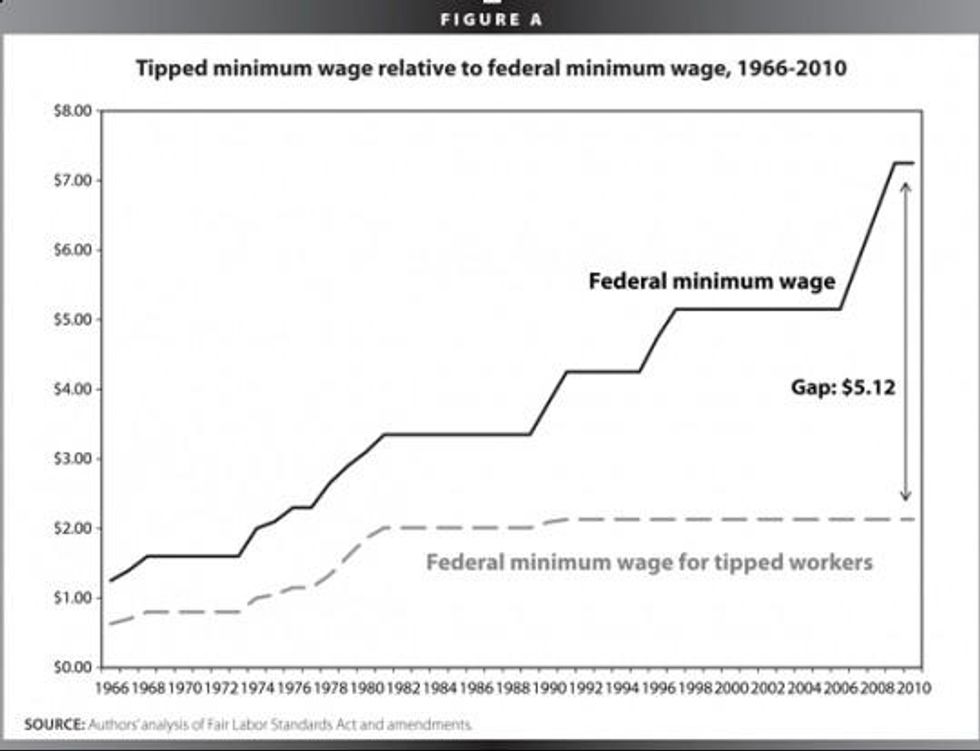

The minimum wage for tipped workers--known as the "tip credit" or "subminimum wage" system--is just $2.13 an hour, less than a third of the regular federal minimum of $7.25. This rate is based on the assumption that earnings from tips will make up the difference, so total pay will approximate that of other low-wage laborers. Now, as campaigns to raise state and federal minimum wages mushroom nationwide--and with campaigns under way for a $15 per hour wage in fast food joints--the base pay of their fellow workers in diners and cafes seems even more outrageous.

A unique economic relic, the base wage for tipped workers has eroded steadily since 1996, when it was unpegged from the already absurdly low federal minimum. The crumbling value of both wage tiers over the past decade, according to the calculation of advocacy group Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC), amounts to a yawning gap between tipped workers' earnings today and what they would have made had the wage rates been adjusted equitably. All in all, the gap represents a net "loss" of more than $20 billion.

That loss is spread across a workforce of some six million nationwide. The subminimum applies to various tipped service sectors (based essentially on custom), ranging from bussers to massage therapists to nail salon technicians--generally some of the lowest paid, most precarious jobs. Most are in the restaurant industry, working as bartenders and servers.

The total wages earned by tipped workers typically add up to about $8.75. While that's more than the absolute base pay, advocates say that the subminimum wage structure overall undermines their earnings and economic security. According to the progressive think tank Economic Policy Institute, "Tipped workers are more than twice as likely to fall under the federal poverty line, and nearly three times as likely to rely on food stamps, as the average worker."

The law basically leaves it up to the consumer to provide the bulk of workers' earnings. So the customer is always right in determining the worth of a worker's labor--whether it's the guy who gropes her as she refills his glass, or the grumpy patron who sends the steak back twice and storms out before the check arrives.

But thanks to fierce campaigning and worker organizing by groups like ROC, tipped workers have won some incremental victories. New Jersey, which just passed a general minimum wage hike, is considering a proposed raise in the tip credit wage from $2.13 to $5.93 per hour by 2015. The White House has recommended a similar raise along with a broader proposal to boost the regular federal minimum to $10.10. Parallel legislation has been introduced in the Senate to raise the subminimum to 70 percent of the full minimum.

Providing tipped service workers a reasonable base wage is a matter of gender and racial equality and basic dignity. About 40 percent of tipped workers are people of color, and about two-thirds are women. About 30 percent are parents, many of them single moms.

In testimony gathered by ROC, Jacqueline Porraz, a server in Nampa, Idaho, said, "I have had customers leave me religious pamphlets, business cards, leftover change, and [sometimes] nothing at all as a tip. Needless to say none of those things pay my college loans." With her weekly income sometimes showing up as essentially net zero on her weekly pay stub, she adds, it feels like "almost a slap in the face, when you have only change in your wallet."

States have applied a patchwork of fixes to help plug the wage gap. Seven states, including Oregon and Nevada, have one state wage floor for all workers, tipped and non-tipped; most of these base wages are higher than the federal minimum. Another 26 states have set a tipped minimum wage above the federal level but lower than the state's regular minimum wage.

The powerful industry lobby, National Restaurant Association, claims that paying tipped workers more would hurt the industry and impede employment. Spokesperson Christin Fernandez told FoxNews.com, "This could significantly limit the entry-level opportunities businesses can provide, and as a result, hurt those without the skills or experience and looking to enter the workforce."

However, that argument doesn't square with the experiences of states without a subminimum wage: They have significantly lower poverty rates, and the link is particularly stark for workers of color.

Of course, tipped workers don't need macroeconomic data to understand these absurd inequities. Tiffany Kirk, a bartender at a Houston piano bar, struggles constantly to raise her toddler on wages that amount to about $8 an hour, with a schedule that varies wildly from week to week. Recalling her experience at establishments where tips can run as low as ten percent, she tells The Nation, "You cannot live on your own. You can't. I've been on food stamps, I've had to go to a local food pantry.... I've had my lights and my phone, my Internet turned off."

If tipped workers earned enough to cover these basic expenses, she adds, "It would boost the morale, I think turnover rates wouldn't be so high [and] customer service would be improved." And that would feed into better economic prospects for everyone. According to ROC, if Washington brought the hourly wage floor for tipped and non-tipped workers to $10.10, the extra wages in tips would pump a $12.7 billion stimulus into the economy.

For workers like Kirk, the statistics matter less than her hope that one of these days, she'll take home a paycheck that maybe feels worth the days she's dragged herself to work sick, or allows her to go a day without worrying about getting evicted. "Honestly, all servers and bartenders want is for people to realize that our whole job is to take care of them," she says, and that, for now, tipped workers' income depends all too much "on how much they leave us."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The person who serves you lunch today may work for a minimum hourly wage that's less than the price of your coffee. And no matter how generous your tip, at the end of the day, she'll take home much less in wages than what she deserves. Federal law has been exploiting workers like her for years, according to labor advocates, thanks to an ultra-low wage floor that systematically cheats servers, bartenders, hairdressers and others of a fair day's pay.

The minimum wage for tipped workers--known as the "tip credit" or "subminimum wage" system--is just $2.13 an hour, less than a third of the regular federal minimum of $7.25. This rate is based on the assumption that earnings from tips will make up the difference, so total pay will approximate that of other low-wage laborers. Now, as campaigns to raise state and federal minimum wages mushroom nationwide--and with campaigns under way for a $15 per hour wage in fast food joints--the base pay of their fellow workers in diners and cafes seems even more outrageous.

A unique economic relic, the base wage for tipped workers has eroded steadily since 1996, when it was unpegged from the already absurdly low federal minimum. The crumbling value of both wage tiers over the past decade, according to the calculation of advocacy group Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC), amounts to a yawning gap between tipped workers' earnings today and what they would have made had the wage rates been adjusted equitably. All in all, the gap represents a net "loss" of more than $20 billion.

That loss is spread across a workforce of some six million nationwide. The subminimum applies to various tipped service sectors (based essentially on custom), ranging from bussers to massage therapists to nail salon technicians--generally some of the lowest paid, most precarious jobs. Most are in the restaurant industry, working as bartenders and servers.

The total wages earned by tipped workers typically add up to about $8.75. While that's more than the absolute base pay, advocates say that the subminimum wage structure overall undermines their earnings and economic security. According to the progressive think tank Economic Policy Institute, "Tipped workers are more than twice as likely to fall under the federal poverty line, and nearly three times as likely to rely on food stamps, as the average worker."

The law basically leaves it up to the consumer to provide the bulk of workers' earnings. So the customer is always right in determining the worth of a worker's labor--whether it's the guy who gropes her as she refills his glass, or the grumpy patron who sends the steak back twice and storms out before the check arrives.

But thanks to fierce campaigning and worker organizing by groups like ROC, tipped workers have won some incremental victories. New Jersey, which just passed a general minimum wage hike, is considering a proposed raise in the tip credit wage from $2.13 to $5.93 per hour by 2015. The White House has recommended a similar raise along with a broader proposal to boost the regular federal minimum to $10.10. Parallel legislation has been introduced in the Senate to raise the subminimum to 70 percent of the full minimum.

Providing tipped service workers a reasonable base wage is a matter of gender and racial equality and basic dignity. About 40 percent of tipped workers are people of color, and about two-thirds are women. About 30 percent are parents, many of them single moms.

In testimony gathered by ROC, Jacqueline Porraz, a server in Nampa, Idaho, said, "I have had customers leave me religious pamphlets, business cards, leftover change, and [sometimes] nothing at all as a tip. Needless to say none of those things pay my college loans." With her weekly income sometimes showing up as essentially net zero on her weekly pay stub, she adds, it feels like "almost a slap in the face, when you have only change in your wallet."

States have applied a patchwork of fixes to help plug the wage gap. Seven states, including Oregon and Nevada, have one state wage floor for all workers, tipped and non-tipped; most of these base wages are higher than the federal minimum. Another 26 states have set a tipped minimum wage above the federal level but lower than the state's regular minimum wage.

The powerful industry lobby, National Restaurant Association, claims that paying tipped workers more would hurt the industry and impede employment. Spokesperson Christin Fernandez told FoxNews.com, "This could significantly limit the entry-level opportunities businesses can provide, and as a result, hurt those without the skills or experience and looking to enter the workforce."

However, that argument doesn't square with the experiences of states without a subminimum wage: They have significantly lower poverty rates, and the link is particularly stark for workers of color.

Of course, tipped workers don't need macroeconomic data to understand these absurd inequities. Tiffany Kirk, a bartender at a Houston piano bar, struggles constantly to raise her toddler on wages that amount to about $8 an hour, with a schedule that varies wildly from week to week. Recalling her experience at establishments where tips can run as low as ten percent, she tells The Nation, "You cannot live on your own. You can't. I've been on food stamps, I've had to go to a local food pantry.... I've had my lights and my phone, my Internet turned off."

If tipped workers earned enough to cover these basic expenses, she adds, "It would boost the morale, I think turnover rates wouldn't be so high [and] customer service would be improved." And that would feed into better economic prospects for everyone. According to ROC, if Washington brought the hourly wage floor for tipped and non-tipped workers to $10.10, the extra wages in tips would pump a $12.7 billion stimulus into the economy.

For workers like Kirk, the statistics matter less than her hope that one of these days, she'll take home a paycheck that maybe feels worth the days she's dragged herself to work sick, or allows her to go a day without worrying about getting evicted. "Honestly, all servers and bartenders want is for people to realize that our whole job is to take care of them," she says, and that, for now, tipped workers' income depends all too much "on how much they leave us."

The person who serves you lunch today may work for a minimum hourly wage that's less than the price of your coffee. And no matter how generous your tip, at the end of the day, she'll take home much less in wages than what she deserves. Federal law has been exploiting workers like her for years, according to labor advocates, thanks to an ultra-low wage floor that systematically cheats servers, bartenders, hairdressers and others of a fair day's pay.

The minimum wage for tipped workers--known as the "tip credit" or "subminimum wage" system--is just $2.13 an hour, less than a third of the regular federal minimum of $7.25. This rate is based on the assumption that earnings from tips will make up the difference, so total pay will approximate that of other low-wage laborers. Now, as campaigns to raise state and federal minimum wages mushroom nationwide--and with campaigns under way for a $15 per hour wage in fast food joints--the base pay of their fellow workers in diners and cafes seems even more outrageous.

A unique economic relic, the base wage for tipped workers has eroded steadily since 1996, when it was unpegged from the already absurdly low federal minimum. The crumbling value of both wage tiers over the past decade, according to the calculation of advocacy group Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC), amounts to a yawning gap between tipped workers' earnings today and what they would have made had the wage rates been adjusted equitably. All in all, the gap represents a net "loss" of more than $20 billion.

That loss is spread across a workforce of some six million nationwide. The subminimum applies to various tipped service sectors (based essentially on custom), ranging from bussers to massage therapists to nail salon technicians--generally some of the lowest paid, most precarious jobs. Most are in the restaurant industry, working as bartenders and servers.

The total wages earned by tipped workers typically add up to about $8.75. While that's more than the absolute base pay, advocates say that the subminimum wage structure overall undermines their earnings and economic security. According to the progressive think tank Economic Policy Institute, "Tipped workers are more than twice as likely to fall under the federal poverty line, and nearly three times as likely to rely on food stamps, as the average worker."

The law basically leaves it up to the consumer to provide the bulk of workers' earnings. So the customer is always right in determining the worth of a worker's labor--whether it's the guy who gropes her as she refills his glass, or the grumpy patron who sends the steak back twice and storms out before the check arrives.

But thanks to fierce campaigning and worker organizing by groups like ROC, tipped workers have won some incremental victories. New Jersey, which just passed a general minimum wage hike, is considering a proposed raise in the tip credit wage from $2.13 to $5.93 per hour by 2015. The White House has recommended a similar raise along with a broader proposal to boost the regular federal minimum to $10.10. Parallel legislation has been introduced in the Senate to raise the subminimum to 70 percent of the full minimum.

Providing tipped service workers a reasonable base wage is a matter of gender and racial equality and basic dignity. About 40 percent of tipped workers are people of color, and about two-thirds are women. About 30 percent are parents, many of them single moms.

In testimony gathered by ROC, Jacqueline Porraz, a server in Nampa, Idaho, said, "I have had customers leave me religious pamphlets, business cards, leftover change, and [sometimes] nothing at all as a tip. Needless to say none of those things pay my college loans." With her weekly income sometimes showing up as essentially net zero on her weekly pay stub, she adds, it feels like "almost a slap in the face, when you have only change in your wallet."

States have applied a patchwork of fixes to help plug the wage gap. Seven states, including Oregon and Nevada, have one state wage floor for all workers, tipped and non-tipped; most of these base wages are higher than the federal minimum. Another 26 states have set a tipped minimum wage above the federal level but lower than the state's regular minimum wage.

The powerful industry lobby, National Restaurant Association, claims that paying tipped workers more would hurt the industry and impede employment. Spokesperson Christin Fernandez told FoxNews.com, "This could significantly limit the entry-level opportunities businesses can provide, and as a result, hurt those without the skills or experience and looking to enter the workforce."

However, that argument doesn't square with the experiences of states without a subminimum wage: They have significantly lower poverty rates, and the link is particularly stark for workers of color.

Of course, tipped workers don't need macroeconomic data to understand these absurd inequities. Tiffany Kirk, a bartender at a Houston piano bar, struggles constantly to raise her toddler on wages that amount to about $8 an hour, with a schedule that varies wildly from week to week. Recalling her experience at establishments where tips can run as low as ten percent, she tells The Nation, "You cannot live on your own. You can't. I've been on food stamps, I've had to go to a local food pantry.... I've had my lights and my phone, my Internet turned off."

If tipped workers earned enough to cover these basic expenses, she adds, "It would boost the morale, I think turnover rates wouldn't be so high [and] customer service would be improved." And that would feed into better economic prospects for everyone. According to ROC, if Washington brought the hourly wage floor for tipped and non-tipped workers to $10.10, the extra wages in tips would pump a $12.7 billion stimulus into the economy.

For workers like Kirk, the statistics matter less than her hope that one of these days, she'll take home a paycheck that maybe feels worth the days she's dragged herself to work sick, or allows her to go a day without worrying about getting evicted. "Honestly, all servers and bartenders want is for people to realize that our whole job is to take care of them," she says, and that, for now, tipped workers' income depends all too much "on how much they leave us."