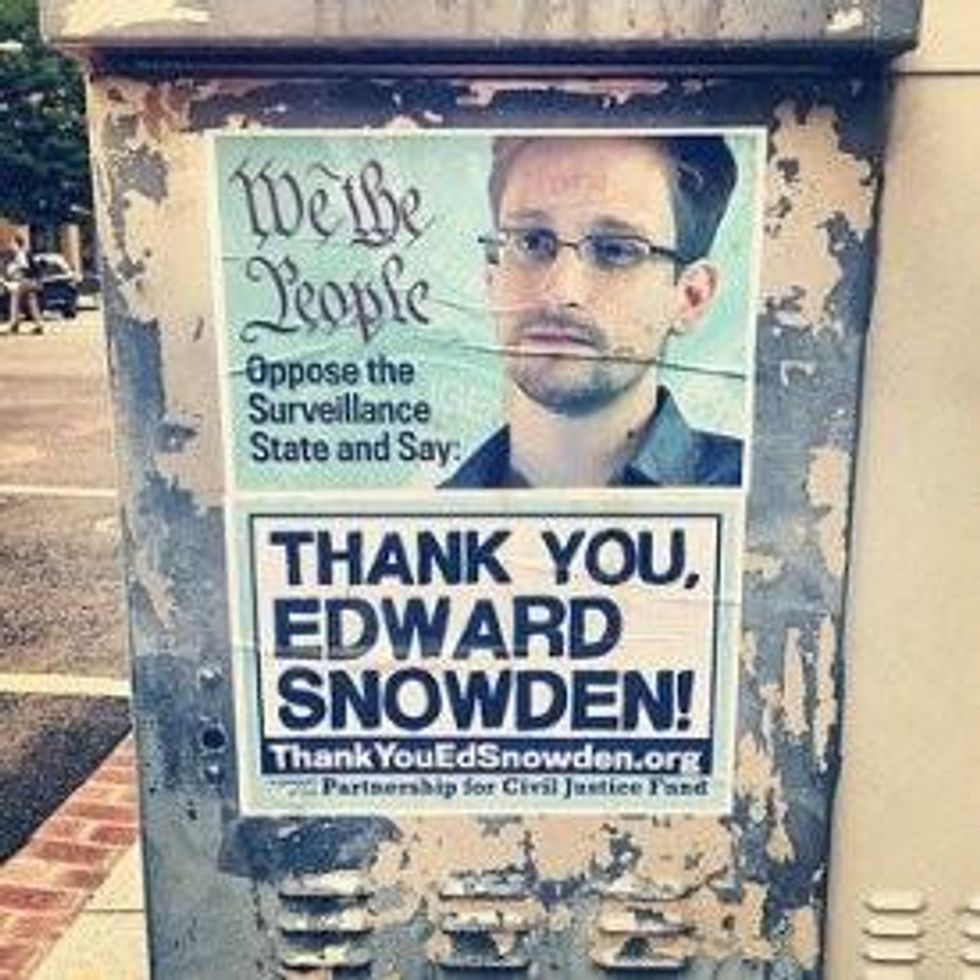

The Snowden revelations about the mass surveillance programmes of the NSA and the complicity of other Western security agencies have generated a lot of talk about the supposed lack of trust in the Internet, current Internet governance mechanisms, and the multistakeholder governance model. These revelations have been crucial to fueling the surveillance reform effort (see CDT's NSA surveillance reform work here). However, most commentary linking surveillance and global Internet governance conflates two important issues in inaccurate - and politically motivated - ways, driving long-standing and potentially damaging agendas related to the management of the Internet.

The Snowden revelations were not just welcomed by

human rights organizations seeking to limit state power to conduct communications surveillance. They have also been well-received by those who seek to discredit existing approaches to Internet governance. There has been a long-running antipathy among a number of stakeholders to the United States government's perceived control of the Internet and the dominance of US Internet companies. There has also been a long-running antipathy, particularly among some governments, to the distributed and open management of the Internet, which has flourished without much government intervention at all. These tensions have been simmering since the first World Summit on the Information Society in 2003, when ICANN and the issue of critical Internet resources (IP addressing and the DNS) were the focus of much attention and concern. These themes of government control, and the role of the US in particular, have reoccurred ever since and continue to frame discussions currently underway in numerous fora, including the upcoming

NETmundial meeting on Internet governance in Brazil.

In these discussions, some governments are using the Snowden revelations to feed more general concerns about the existing systems of Internet governance, and to call for a new international multilateral (that is, government-dominated) governance order. For example, the government of Pakistan - supported by Ecuador, Venezuela, Cuba, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Russia, Indonesia, Bolivia, Iran, and China - made a statement at the 24th session of the Human Rights Council in September 2013, that expressly linked the revelations about surveillance programs, the need for a new international governance framework, and the clear failure of the Internet Governance Forum to deliver on "its desired results." But blaming US government surveillance practices on a failure of multistakeholder Internet governance is fallacious and misleading.

Mass surveillance programs have developed not due to some failure of participatory Internet governance processes, but rather through deliberate actions, taken by governments, that disregard the fundamental rights of their citizens and people both inside and outside their territory. Governments have developed national-level law and policy, colluded with one another through intergovernmental agreements, and co-opted private actors into their surveillance schemes - all under a veil of secrecy intended to keep non-governmental stakeholders out of the deliberations. Increasing government control over Internet governance will not change that - it would almost certainly make the situation much worse. We have surveillance programmes that abuse human rights and lack in transparency and accountability precisely because we do not have sufficiently robust, open, and inclusive debates around surveillance and national security policy. Indeed, even in those countries that purport to be the most open and transparent and that are consistent supporters of the multi-stakeholder model, surveillance and security policy remain, unfortunately, for the state alone. Linking the Snowden revelations to a failure of open and participatory multistakeholder Internet governance is simply nonsense.

Governments are using the Internet to undermine our fundamental rights and threaten, as the UN Special Rapporteur Frank La Rue has suggested, the foundations of democratic society. Our response should not be to increase government control over the management of the Internet. Instead, we should reaffirm the need for open, inclusive, participatory Internet governance processes (nationally and internationally) and resist unilateral or multilateral decision-making on Internet-related policy issues.