We've just crossed a sobering milestone. For the first time since humans have walked the planet, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at Mauna Loa Observatory has reached 400 parts per million. On May 9, scientists from both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography measured the daily average concentration of carbon dioxide in air above this value. I don't know about you, but when I heard this I wanted to cry. Let me put this in context for you.

I started my scientific life as a fresh-faced glaciologist drilling ice cores on the immense ice sheet of Antarctica. It was the early 1990s and my job (an amazing one, I'll admit!) was to tirelessly process the ancient ice that we were bringing up from the deep drill hole. There was almost a mile of ice to analyze! This frozen archive is made from pure snow that fell on the continent tens of thousands of years ago and compressed into hard, cold ice. These ice cores, like many others since, reveal the secrets of ancient atmospheres from the air bubbles trapped within their lattice. They allow us to compare the modern atmosphere that is measured at Mauna Loa with what happened in the past.

Past atmospheres: the cycles of CO2 and temperature

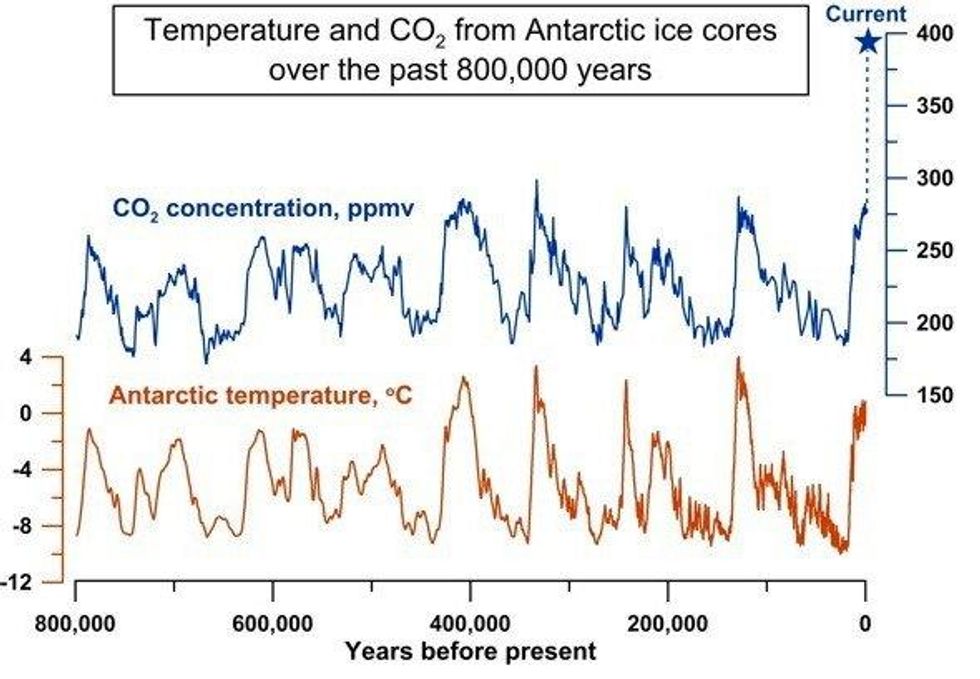

I remember my excitement on seeing the cycles of ice ages pop out from our analysis. You've probably seen those graphs of wavy lines that show carbon dioxide dancing between a low level during an ice age and a high level in an interglacial (like the one we are in now).

"I don't know about you, but when I heard this I wanted to cry."

For the last eight glacial cycles carbon dioxide has varied between 180 parts per million and 280 parts per million. Carbon dioxide has, in general, gone up and down hand in hand with global average temperature. When carbon dioxide is high, temperature is high; when carbon dioxide is low, temperature is low, with the leads and lags being well understood by the scientists studying these in detail. The ice core record shows this has been the natural cycle for at least 800,000 years. As a yardstick, homo sapiens has only been around for a mere 200,000 years at the very longest. Earth's climate is very sensitive to the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But in the last two centuries of our short time on the planet we have altered the atmosphere drastically.

The cycles of carbon dioxide and temperature over the last eight ice ages show CO2 concentration varying between 180ppm and 280ppm. Carbon dioxide concentration is now at unprecedented levels in human history. Adapted from Luthi et al, 2008

Climate change: thickening CO2 blanket warms the world

At about the same time I was getting cold fingers from handling old ice, we had just passed the ominous 350 parts per million mark. Knowing what scientists knew then about the relationship between carbon dioxide emissions and temperature (see the First IPCC Assessment from 1990 here and the IPCC Supplementary Report from 1992 here), I could not imagine two decades later carbon dioxide levels would still be soaring upwards. But they are.

Carbon dioxide naturally forms a heat-trapping blanket around the earth - we can't live without it. But our human practice over the last two centuries of digging up ancient sunlight in the form of oil, coal, and natural gas and then burning it has released excess carbon into the atmosphere.

For almost a million years, the earth cycled between roughly a two-blanket world (180 parts per million) and a three-blanket world (280 parts per million). By perturbing the atmosphere to this new level, we've managed to bump that up to a four-blanket world (now 400 parts per million) in a very short time. And we're starting to feel it get hot under here.

Welcome to the Pliocene!

The last time the atmosphere had 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide was most likely between 3 and 5 million years ago, long before humans like us inhabited the earth. It was a geological epoch known as the Pliocene. The planet was many degrees warmer and scientists estimate sea level was about 80 feet higher.

Reaching 400 parts per million for the first time in human history is a wake up call for all of us. The science is clear. It's high time we addressed the fundamental drivers of climate change -- heat-trapping emissions from fossil fuels as well as deforestation practices which emit carbon and reduce the uptake of carbon dioxide.

If we don't take action, in a couple of decades as we mark the passing of the next ominous milestone of 450 parts per million at Mauna Loa, there may be no returning to the climate we once knew.