American aid to the country once called Zaire appeared to have an amazing effect.

The more the US gave its ruler, Mobutu Sese Seko, the shorter Zaire's roads seemed to get. By the time Mobutu was overthrown in 1997, after two decades of American and other western largesse, his country had just about one tenth of the paved roads it had had at independence in the early Sixties. Once US aid shrank, the roads started getting longer again.

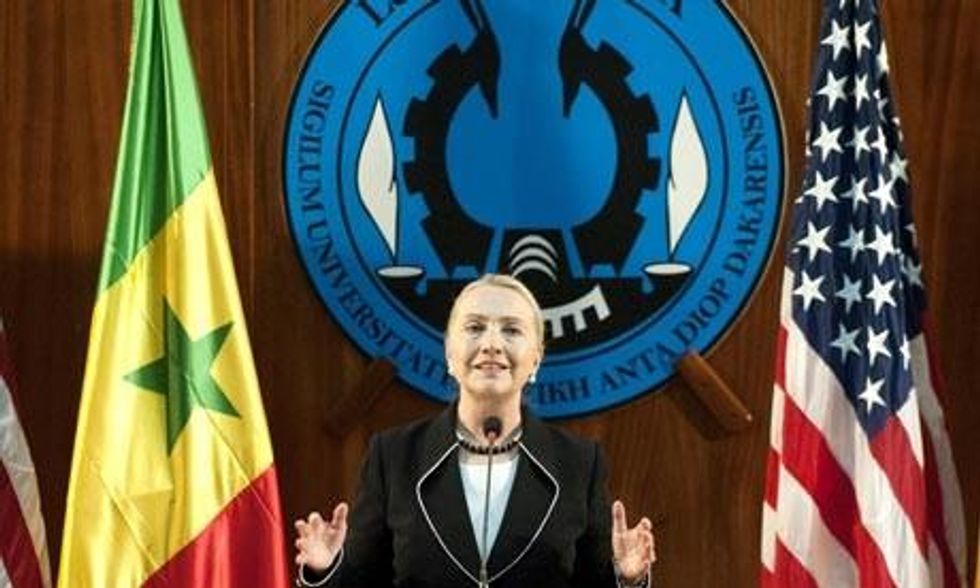

Hillary Clinton, the US secretary of state, began a tour of Africa this month with a thinly veiled warning that China is out to plunder the continent and its governments would do well to huddle under the protective wing of America's commitment to freedom. Clinton told an audience in Senegal that, unlike other countries:

"America will stand up for democracy and universal human rights even when it might be easier to look the other way and keep the resources flowing."

She didn't mention China by name, but everyone got the message. The US secretary of state is getting at a point made by other critics of Beijing's role in Africa: that China is so hungry for resources it does deals with authoritarian regimes and doles out aid without consideration of issues such as good governance.

That sounds an awful lot like what the US and its allies got up to for decades - with the difference that Chinese aid does sometimes deliver something tangible, such as thousands of kilometres of new roads in the former Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo. Whereas US aid mostly disappeared into Mobutu's buoyant bank accounts, or was used to buy off the army to keep him in power, China's deal with the DRC government - trading thousands of kilometres of new roads and rehabilitated railway track for copper and other minerals - is transforming lives by linking up parts of the country cut off from each other for decades except by air.

None of this happened with US and western money. US aid to Mobutu was tied up with the cold war, his support of US-backed rebels fighting Angola's Marxist government and his general hostility to communism. Barely a word was said - by successive US administrations - about Mobutu's dire human rights record. Few questions were asked about how, despite the billions of dollars thrown at Kinshasa, Mobutu went on getting richer while the people he ruled got poorer and his country's infrastructure fell apart.

Mobutu was always welcome at Ronald Reagan's White House, where the president called him "a voice of good sense and goodwill". Only after the end of the cold war did US policy shift. Washington didn't need Mobutu anymore. Finally, it could afford to talk about principles without much cost.

It was much the same story with western aid to Rwanda. Hundreds of millions were poured into the tiny country, with France leading the way, to support a regime that would ultimately resort to genocide in an attempt to hang on to power. Yet, it took the Chinese to lift towns such as Kibuye out of their isolation.

Kibuye is just 120km, or 75 miles, west from Rwanda's capital, Kigali. Twenty years ago, the journey was as much as an eight-hour drive, depending on the rains and on whether, as seemed to happen most days, a bus or lorry was stuck in the deep muddy ravines that opened up on what could only be loosely described as a road. China's road-builders changed all that, and the journey now is well under two hours - with all the benefits to trade, education and family life that brings.

The pattern across Africa was US support for ideological allies, which included Washington siding with the apartheid regime in South Africa while banning Nelson Mandela's ANC as a terrorist organisation. It also entailed funding of wars against opponents. Human rights and democracy were too often buried under the needs of cold war realpolitik, as Washington saw them.

US officials argue that "that was then", and it's different now. But is it? For sure, Washington will make a stand on "democracy and universal human rights" where it does not conflict in a major way with other interests. But where money or security are involved it's another matter.

Take Equatorial Guinea. Washington had plenty of public criticism for its appalling and bloodstained dictator, Teodoro Obiang Nguema, who has ruled since 1979. The US even pulled out its ambassador, John Bennett, in 1993 after he was accused of being a witch on state radio and threatened with violence. In his departure speech, Bennett named the regime's worst torturers and Washington closed the embassy three years later. Then, large reserves of oil were discovered in the 1990s: American companies started pumping and everything changed.

Or take Ethiopia. The US is the largest contributor of aid to Addis Ababa, which has been ruled by the same man, Meles Zenawi, for 20 years. He's received billions of dollars in aid, since American largesse rose sharply after the 9/11 attacks (from a little more than $200m a year to close to $1bn) because Washington came to regard Ethiopia as a frontline in the "war on terror", owing to the presence of Islamist fighters in neighbouring Somalia. The CIA also used Ethiopia as a base for the secret interrogation of hundreds of detainees abducted from other countries, which was likely to have involved torture.

While some of that aid money has benefited ordinary people, a Human Rights Watch report two years ago said Zenawi was "using aid to build a single-party state". It accused the ruling Ethiopian Peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front of exercising "total control of local and district administrators to monitor and intimidate individuals at household level" and charged that foreign governments, including the US, were colluding in this repression.

A BBC investigation last year exposed how "the Ethiopian government is using billions of dollars of development aid as a tool for political oppression." It reported that villages failing to support Zenawi are starved of food, seeds and fertiliser.

For all of Clinton's assurances, the US still finds it easier to look the other way.