This week, cellphone carriers publicly reported that US law enforcement made an astounding 1.3m demands for customer text messages, caller locations, and other information last year. The disclosure has sparked a flood of press coverage and consumer outrage, given much of the information was obtained without a warrant.

But this is only one way that communications and communications records are being monitored by the government. Since 2006, Americans have known that the National Security Agency (NSA), in league with telecommunications carriers like AT&T, has been engaging in mass warrantless surveillance of millions of ordinary Americans. And since shortly thereafter, the Electronic Frontier Foundation has been suing to stop it.

Despite the fact that the mass wiretapping was first exposed by the New York Times in 2005, and subsequently reported on by dozens of news organizations, the government continues to maintain that the "state secrets" privilege should prevent the courts from even the basic determination of whether the NSA's actions are legal or constitutional. This position isn't correct legally, since, in 1978, Congress created the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance law specifically requiring the courts to determine the legality of electronic surveillance. But it also isn't the right answer for a country founded on the supremacy of law and the constitutional protections against untargeted searches and seizures.

Now, three longtime NSA employees - William E Binney, Thomas A Drake, and J Kirk Wiebe - have come forward and offered additional inside evidence to support the lawsuit, all of which confirms what an increasing mountain of evidence shows: that the US government is engaging in mass dragnet surveillance of innocent, untargeted American people, as well as foreigners whose messages are routed through the US. As Binney states, "the NSA is storing all personal electronic communications."

Our lawsuits - first, against the telecommunications carriers, and now, against the government directly - also included other undisputed evidence from a former AT&T technician named Mark Klein. He provided blueprints and photographs showing an NSA-installed "secret room" in an AT&T facility less than a mile from EFF's San Francisco office, which experts say siphons massive amounts of internet usage data, phone calls and records flowing through the facility directly to the NSA.

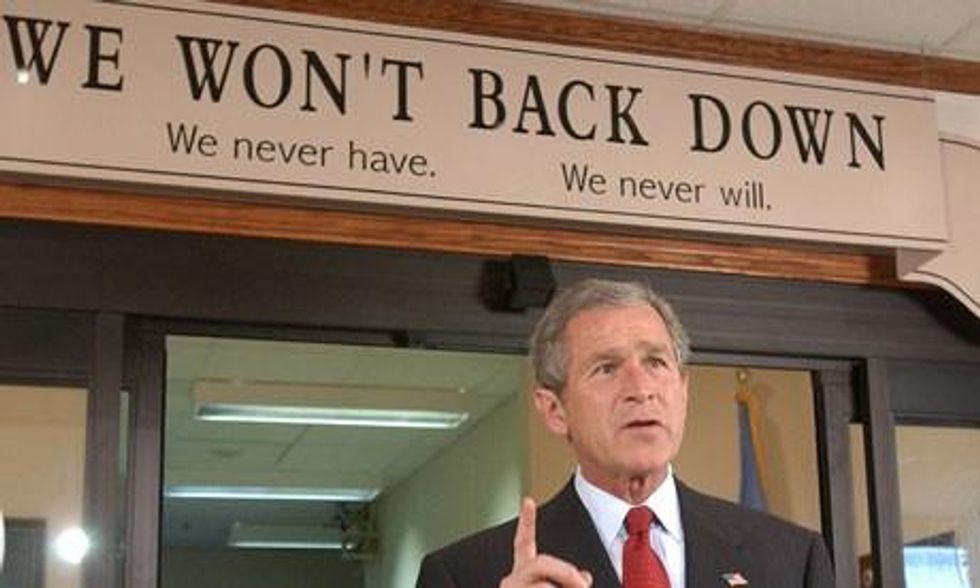

The surveillance has not stopped, either. In 2009, after President George W Bush left office, the New York Times reported that the NSA was still collecting purely domestic communications of Americans' in a "significant and systemic" way. In 2010, the Washington Post reported:

"Every day, collection systems at the National Security Agency intercept and store 1.7bn emails, phone calls and other types of communications."

And a Wired investigation published in March revealed the NSA is currently constructing a huge data center in Utah, meant to store and analyze "vast swaths of the world's communications" from foreign and domestic networks.

The government's response? A preposterous claim that no court can consider the legality of this surveillance unless the government formally admits it. In fact, the government maintains that even if all the allegations are true, the case should be thrown out under the state secret privilege.

The courts should not participate in this charade, nor should the American people or Congress. We are currently asking the court to rule that the 1978 FISA law supersedes the government's claim of state secrets and requires the court to rule on the legality of the surveillance.

And in Congress, two US senators, Ron Wyden and Mark Udall, have been asking the NSA for a year simply for a ballpark figure of how many Americans have had their communications surveilled by the spy agency. The NSA finally responded two weeks ago, claiming it did not have the capacity to find such number. Apparently unaware of the irony, the NSA argued that releasing an estimate of how many people's emails they read would violate Americans' privacy.

Sadly, the UK government seems to be following suit, proposing its own mass surveillance plan, asking Parliament to pass a law allowing the government to monitor every email, text and phone call in the country. But at least in the UK, the plan is now public - after an earlier secret one was inadvertently revealed.

Whether the threat comes from the warrantless surveillance of our cell phone location data by the local police, or the wholesale collection of our emails and phone calls by the NSA, all citizens deserve reasonable privacy in our communications. And we assert the right to hold the government accountable for violating that privacy.