My chosen epitaph: “He helped to end the Vietnam War, and he struggled to prevent nuclear weapons from being exploded ever again.” —Daniel Ellsberg (1931-2023)

My father was a complicated man. On the one hand, he had an acute appreciation for beauty in all its forms: music, poetry, the sound of the ocean, the colors of the sunset visible from his dining room in Kensington. After his death I found a closet piled high with packets of photographs—almost all of them closeup shots of flowers. He kept a frequently updated anthology consisting of photocopies of his favorite poems, many of which he had memorized and remained capable of reciting even in his last months.

All of this was in contrast with his long-standing preoccupation with the darkest moments of history, and the potential for greater tragedies to come. The bookshelves that surrounded his downstairs office were sorted according to labels such as Torture; Bombing Civilians; Nuclear First Strike; Terrorism; Lies; Genocide; and finally, Catastrophe. As he noted in one of his last interviews in the New York Times, he spent so much of his life thinking about these things not because he found them fascinating, but because he wished to make them literally unthinkable. In his efforts to alert the world to the danger of nuclear annihilation, he engaged in action (including almost a hundred acts of civil disobedience), gave countless speeches and interviews, and wrote an extraordinary memoir, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner. Yet by the end of his life, acknowledging the lack of progress in achieving his goals, he expressed regret that he hadn’t done more.

All the while, it could be said that a major part of his life was spent thinking—trying to understand and unravel the mysteries of the human condition and to devise ways of thinking that might turn the tide of history. He could sit for hours, occasionally scribbling his almost illegible notes onto a yellow pad, otherwise staring into his own private abyss.

Many of his central concerns are reflected in the writings compiled in this volume. They show that he was not just concerned with the political or strategic aspects of war and nuclear planning—problems that could be fixed with a change in leadership or better policies. These threats to human survival were rooted in certain deep-seated problems with humanity itself. Some of these pertained to human nature in general: our willingness, almost unique in the animal world, to kill members of our own species. Then there was the tendency to derive our identity from our membership in a group, which set limits on our capacity for empathy with outsiders, those considered the “others.”

We are a very flawed species, dangerously so. We are dangerous to ourselves in the short and long run and we are the enemy that threatens the long-run survival of most other species. Seeing humanity’s flaws, depression sets in. I am ashamed of my species, and I am sad for us and other species.

But other problems were more specific to the nature of rational, bureaucratized organizations in which individuals were encouraged to subordinate individual ethics (“which deal largely with obligations toward and concerns for others than oneself”) to the ethics of the organization, defined in terms of obedience to authority, or loyalty to the boss or the “team.” This tendency was compounded by the compartmentalization that made it easier for bureaucrats to deny their sense of personal responsibility for the outcome or consequences of official policy.

In the years following the end of his trial in 1973 for his part in copying and revealing the Pentagon Papers, he engaged in a wide-ranging study of these problems. He considered the example of Nazi Germany, examining the various forms of complicity, whether on the part of the masses, on the part of soldiers and officers who executed immoral policies, or on the part of officials. Among these was Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, who alone among the Nuremberg defendants pleaded guilty, even for things in which he had not been directly involved.

As Speer explained: “For being in a position to know and nevertheless shunning knowledge creates direct responsibility for the consequences—from the very beginning.” This view resonated with my father’s experience of what he called the “moral stupidity” shared by many organization men, motivated by the desire not only to keep one’s job but “to keep one’s status, one’s self-image (as a good person, as tough/manly, autonomous, obedient, loyal), and the good opinion of teammates, bosses, sponsors, constituents, and allies.”

In a lecture in May 1971 titled “The Responsibility of Officials in a Criminal War,” he had copied a quote from Speer in which he found a damning indictment of his own early culpability with regard to Vietnam War policy:

If I was isolated, I determined the degree of my own isolation. If I was ignorant, I ensured my own ignorance. If I did not see, it was because I did not want to see. . . . It is surprisingly easy to blind your moral eyes. I was like a man following a trail of bloodstained footprints through the snow without realizing someone has been injured.

My father spent many years reflecting on the work of the psychologist Stanley Milgram, whose controversial experiments at Yale were recounted in his book Obedience to Authority. Milgram had devised an experiment in which unsuspecting subjects were assigned the role of conducting a test of memory. This test involved the testers’ obligation to punish wrong answers by applying shocks of increasing voltage to a supposed “learner” (actually an actor in a separate room). The subjects were instructed by the “scientist” to continue with the test, even when, disturbed by the “learners’” protests and cries of pain, they wondered whether they should continue. They were told that it was necessary to complete the test and assured that while the shocks were “painful,” they caused no “permanent tissue damage.” Non-answers were to be treated as false answers, and many subjects continued to apply the shocks even when the “learner” fell silent. The disturbing revelation of the experiment was how compliant the subjects were in obeying authority, even when doing so caused them personal stress (the reason that such an experiment was later deemed unethical).

The mechanisms of this obedience, and what lessons it might offer about how to break the spell and induce disobedience or dissent, was for my father a topic of deep interest and importance. In his copy of Obedience to Authority, he heavily underlined one of the permutations in the experiment in which the “subject” was exposed to the example of a fellow “subject” (in fact, another actor) who said, “This is crazy! I refuse to continue.” Milgram learned that in cases where subjects were exposed to an example of conscientious disobedience, they were able to awaken from their hypnotic captivity to authority.

What would save us, he believed, might require some wholesale evolution of human consciousness. Did we have time to achieve this?

He examined lessons from anthropology, history, and psychology. He studied the example of dissidents and those who acted on the basis of conscience, who took responsibility to act even at great personal risk. To understand these dynamics, he believed, was not just a matter of intellectual interest. The answers could make all the difference in ensuring a future for humanity.

And as his notes make clear, these reflections on averting catastrophe had deep personal roots. He noted, “When I was fifteen, I experienced a catastrophe.” The story of “the Accident” that took the life of his mother and younger sister is described in detail in the opening section of this book. There he confined himself to recounting the story from various angles, without reflecting on the ways it may have affected his life—his own sense of survivor’s guilt, his capacity for risk taking, even his vocation as a whistleblower. But the ease, in his notes, with which he intersperses reflections on this story with his more wide-ranging reflections on authority, obedience, culpability in the face of disaster, and the responsibility to raise an alarm (“to tell truths that might save lives”) shows that the connections were a matter of conscious reflection.

Over and over, he continued to deconstruct the events and their meaning. Was his father to blame for falling asleep at the wheel? Was his mother to blame for forcing him to keep an appointment she had made to attend a birthday party for her brother in Denver? Was he in part to blame on account of his impending decision to abandon his assigned destiny as a concert pianist?

He could draw the parallel between his own fear of losing a mother’s love and the organizational or group conscience that made it unthinkable for so many officials to become whistleblowers: to be seen by their colleagues as disloyal, apostates, violators of trust, unworthy of being considered an insider. This parallel led him constantly to reflect on his own example. What had allowed him, in particular, to break free? To defect? To cease the desire to be the president’s man? To raise the alarm that someone you trusted, a figure of authority, might be asleep at the wheel?

Many of the flaws in humanity have been evident throughout history, from biblical narratives of holy war to the Iliad to the mad destructiveness of World War I and the many examples of genocide, of which the Holocaust stood out not just by its scale but by the application of mechanized, industrial methods of execution. And yet with the splitting of the atom, humanity had entered a fantastically more perilous stage of history—conceivably the Final Solution to the human problem. Flawed humanity had suddenly become equipped with the technology and scientific knowledge to threaten its own survival.

Einstein observed, in a famous sentence, “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.” To this my father notes: “What change was Einstein calling for? We need to use our human capacity for change on our own propensities—specifically, our readiness to gamble with catastrophe. We need to change what it means to be human.”

The extensive reflection on “what it means to be human” is one of the more surprising themes among these selected thoughts, or pensées, to borrow the title of Blaise Pascal’s famous work. The allusion to Pascal is not casual. The seventeenth-century French scientist and Christian apologist left his most important work in the form of aphoristic notes and fragments for a grand project of Christian apologetics. This project began with his own characterization of the human condition: “Boredom, inconstancy, anxiety.”

Yet for my father, the question of what it means to be human was not oriented, as it was for Pascal, toward the prospect of individual salvation, but toward the survival of all humans and other earthly creatures. What would save us, he believed, might require some wholesale evolution of human consciousness. Did we have time to achieve this? We were like the crew of the Titanic, steaming forward at full speed in fields of ice, racing toward a rendezvous with disaster. Was it already too late? Or was there still time for a mutiny?

The exposure to people who represented a different philosophy of life—based on the power of truth, the priority of life, compassion for others, and willingness to endure sacrifice and suffering in the service of what is right—brought him to a completely new understanding of his life and its purpose.

Reflecting on his own experience, he pondered the factors that had prompted his own awakening to a sense of loyalty and responsibility to something higher than obedience to executive authority—or to a community larger than the organization, the administration, the brotherhood of insiders. What were the steps that tracked this journey?

My father began his career in the late 1950s as a defense analyst for the RAND Corporation, granted access to the most highly classified secrets of our nuclear war planning. His concern was never about fighting a nuclear war, but about preventing it—especially by means of deterrence and an effective system of command and control. He believed this work to be of the highest importance; he was trying to save the world. Yet what he came to recognize was that these plans were characterized, on the one hand, by a fantastic degree of murderousness, far exceeding anything ever imagined, and on the other, at the same time, by an incredible degree of make-believe and fantasy. Together, these two qualities represented a kind of madness, depicted accurately in the film Dr. Strangelove. It was a madness, he later realized, not inconsistent with extreme intelligence and rational capability.

An important turning point came in 1961 when he was presented by the Pentagon with a graph indicating the estimated casualties that would result from executing the existing plan for general nuclear war. This plan called for destroying every city in Russia and China with a population over a hundred thousand. The predicted loss of life from blast and radiation (the latter covering large portions of adjacent allied countries) was six hundred million. (In light of later calculations about the risk of nuclear winter, he realized that even this estimate was a vast understatement.) Of the piece of paper that contained this estimate, he said that it “depicted evil beyond any human project ever.”

That the word “evil” came to his mind was perhaps evidence enough that he was not suited for this line of work. And yet it meant that the execution of evil plans did not require, as many people would suppose, monsters, highly aberrant or “clinically disturbed” people—“people not like us,” as he put it. It could be carried out by intelligent, ordinary family men like his colleagues at RAND, who were neither better nor worse than anyone else. It spoke to Hannah Arendt’s reference to the “banality of evil,” or as he would say, “the banality of evildoing and most evildoers.” From that point, he had one overriding life purpose: to prevent the execution of this plan. He continued to maintain his security clearances and insider status, believing he could best achieve his purpose from within.

His two years in Vietnam (1965–67) as part of an interagency task force to study and offer advice on the war launched the evolution of his own consciousness. The first stage was his exposure to the human reality of the war. The people of Vietnam, he would say, “came to be as real to me as my own hands.” He returned from Vietnam committed to helping our country extricate itself from this futile and mistaken policy.

But then came the experience of reading the Pentagon Papers, a secret history going back to America’s support for the French effort following World War II to recapture its colonies in Indochina. His new understanding of this history changed his entire perspective. Everything the United States had done in Vietnam was an extension of that initial effort by the French—to impose, by force, a regime of our liking on the people of Vietnam.

“Is this right?”—not “Is this mistaken or futile?”—became his predominant question. It was a question he had never heard from his colleagues. Nor was it documented in the Pentagon Papers, in which moral and ethical questions were never raised. “The only questions asked were: Will this work? Is it expedient? Is it worth the risk? Will we get away with it?”

To have continued this war, year after year, for reasons of state, against the wishes of the people we were supposedly defending, was not a mistake but a crime—a crime that had to be resisted. But how? That question was answered in August 1969 when he attended a gathering of war resisters in Haverford, Pennsylvania, where he encountered people who operated from a completely different set of values. Many of them were inspired by the principles of Mohandas Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

One of them was a young man named Randy Kehler, who mentioned in his speech that he would soon be going to prison for refusing to cooperate with the draft. It is impossible to overstate the impact of this encounter on my father. After fleeing the conference room and sobbing for a long time, he asked himself, “What could I do to end this war if I were willing to go to prison?” That question, like the Accident, divided his life in two—a before, and an after.

The exposure to people who represented a different philosophy of life—based on the power of truth, the priority of life, compassion for others, and willingness to endure sacrifice and suffering in the service of what is right—brought him to a completely new understanding of his life and its purpose. And though he continued until his death to deal in political considerations, weighing strategy and tactics that might reduce the risk of nuclear war, his underlying preoccupations centered on moral, and, for want of a better word, “spiritual,” considerations.

He realized that the fate of the earth, threatened by nuclear weapons, made it urgent that we recover our capacity to think in these terms:

What is missing . . . in the typical discussion and analysis of historical or current nuclear policies is the recognition that what is being discussed is dizzyingly insane and immoral: in its almost incalculable and inconceivable destructiveness and deliberate murderousness, its disproportionality of risked and planned destructiveness to either declared or unacknowledged objectives, the infeasibility of its secretly pursued aims . . . its criminality (to a degree that explodes ordinary visions of law, justice, crime), its lack of wisdom or compassion, its sinfulness and evil. (The Doomsday Machine, 348)

He was aware that to speak this way entailed the risk of being dismissed as a fanatic, an extremist, lacking in “objectivity.” And yet, if we are truly to step back from the brink of catastrophe, we must confront the true moral dimension of our problem. By what right—for what reasons of national security or “defense”—could one person or one country presume to gamble with the fate of the world?

He did find himself pondering his vocation, often referring to the mythical seer Cassandra (“a crier in the wilderness”), who was blessed by the gods with the power of seeing the future, yet cursed in that nobody would believe her. In releasing the Pentagon Papers, he had believed that he was perhaps “Cassandra with documents”—that is, armed with the receipts that would justify his warnings that past patterns of lies and escalation were being repeated by the Nixon administration. But his documents, which ended with the Johnson administration, couldn’t prove it. They justified people’s opposition to the war, but most people believed that Nixon was committed to getting the United States out of Vietnam. Seventeen months after the release of the Pentagon Papers, Nixon was reelected in a landslide.

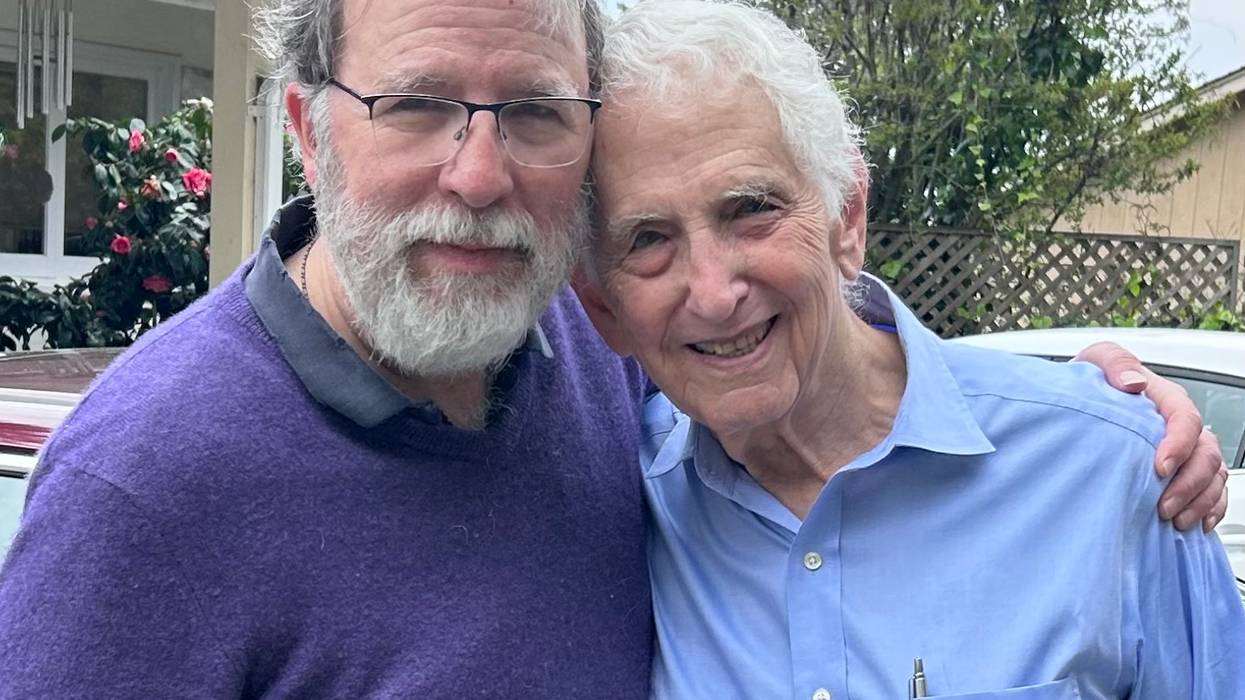

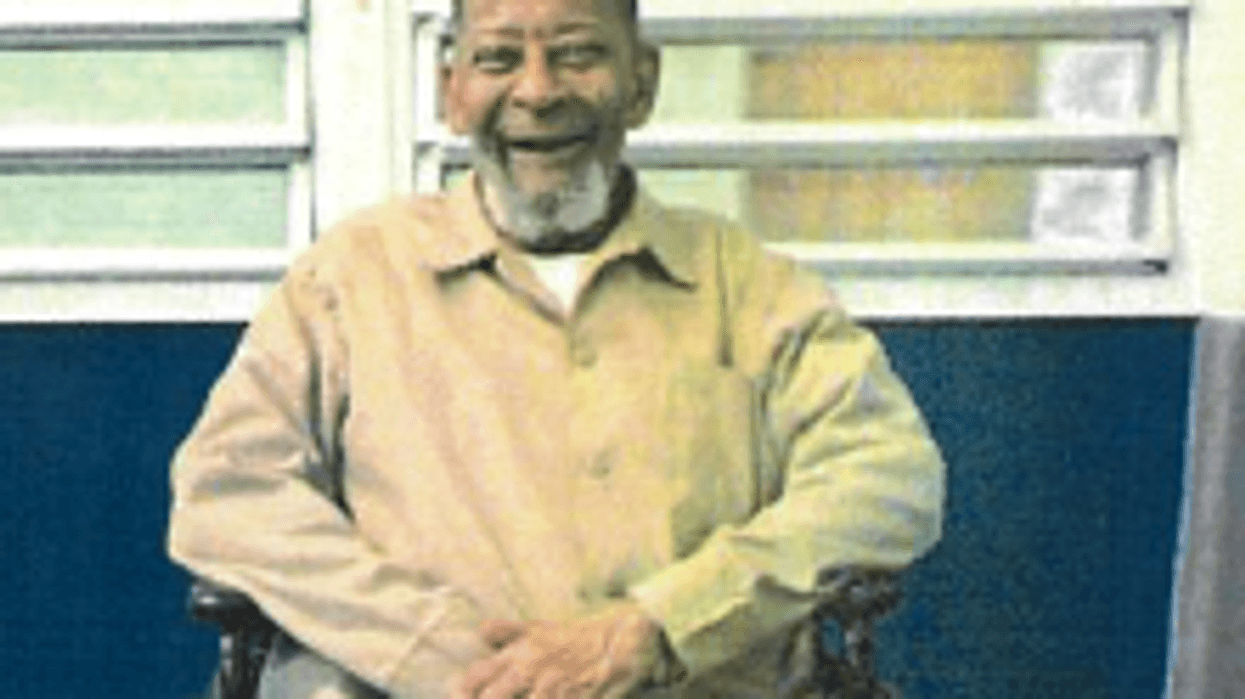

Daniel Ellsberg. (Photo: Courtesy of Robert Ellsberg)

Daniel Ellsberg. (Photo: Courtesy of Robert Ellsberg)

Like Cassandra, my father characterized himself as a “‘doomsayer’ (not to be believed, to be thought mad, extreme).” This characterization applied even more to his warnings about nuclear doomsday. But “as for me,” he added, “I want to change the future—not only foresee and warn.” To do that, he sought to “protest, reveal, risk for others, seek understanding, prevent danger, evaluate risks, avert evil, and teach by word and example.”

Perhaps, he said, the right word for this role was “prophet.” Most people think of prophets as those who are able to foresee the future. Yet the biblical prophets were not fortune-tellers. They were so attuned to the underlying spiritual and moral pathologies of their time that they could soundly anticipate the disaster that was sure to follow. They too wanted to “change the future.” Through their warning they hoped to effect moral and spiritual conversion. They hoped that the people might “choose life,” opt for justice, and restore right relations rather than drift blindly toward destruction.

In words that might have been uttered by Jeremiah, my father noted:

I am living in a society that is preparing a catastrophe.

I taste ashes in the wind.

Unlike the biblical prophets, he did not believe in a personal God. His parents were ardent converts to Christian Science, a faith he himself had been quick to abandon. This rejection extended to an aversion to organized religion in general. Yet at times he seemed to tap into a deeper spiritual spring:

I am seeking wisdom, enlightenment. I am studying, meditating, seeking teachers, looking for explanations and examples of human societies.

And elsewhere:

Can we divest mysticism from its ties to mainstream religion, especially religious beliefs and doctrines? I don’t believe in a God that listens to us, responds to us or protects us (as in war). One can, however, for calm and reassurance, profitably consult with and attune to spiritual energies such as Love, Beauty, Consciousness, and Unity.

The word “conversion” (which in its root means turning around, going in a different direction) appears a number of times, sometimes in personal terms:

What happened to me? I was at the height of my—and RAND’s—influence and prestige. I had the equivalent of a religious conversion: I was “Born Again.”

But in confronting the dangers of our time, he also suggested that what was needed was not just new policies or a revision of our war plans, but a social conversion in the form of moral “evolution.” He did not despair of this possibility. One time, while participating in a protest, he found himself grouped with a cohort of “people of faith.” One of them asked him, “Are you a person of faith?” “No,” he answered, but I am a person of hope.”

I thought of that line during his last months, as I was writing the introduction to a twenty-fifth anniversary edition of a book I had written on saints, prophets, and witnesses for our time. In my introduction I credited his example with leading me to my own calling, remembering and sharing the stories of those throughout history who offered a heroic example of faith, hope, and love in action.

I cited his identity as a person of hope, and noted that in that spirit he had dedicated his life to preserving the planet from the perils of nuclear war. His hope was not an expectation that all would turn out well, but a form of action. I quoted him: “I choose to act as if we had a choice to change the world for the better and avoid catastrophe.”

At the time, he was dying of pancreatic cancer, and I knew he wouldn’t live to see my words in print. But I did have the opportunity to read my introduction aloud to him. He listened intently. I had hoped he would be pleased to hear how his example had played such a role in my own vocation. But he wasn’t. He frowned and said, “I don’t want you to say that.” Was he disturbed by a reminder of my Catholic faith, which he tended to regard as a form of personal rebellion? Or was he made uncomfortable by the implication that he was some kind of saint?

In that light, it was interesting to me, in reading this collection of his notes, to find a surprising reference to my book, and a “lesson” he evidently drew from it:

The lesson of Robert’s book, All Saints, is that these people’s life stories, their examples of sanctity, are healthy to contemplate now, in the late 20th century. These were whole lives of change, not just moments or isolated acts.

Many of the saints were not perfect; they were not irreproachable in all aspects, all the time, all their lives. Doesn’t that make their lives all the more exemplary and inspiring for us?

That was my dad. He knew that he was not irreproachable “in all aspects, all the time,” all his life. But the survival of the world could not wait for irreproachable people. It would require many people of compassion and hope who could recognize the dangers facing our planet and were prepared, as Camus put it, “to speak out clearly and pay up personally.” It would require a kind of awakening to the moral and ethical dimensions of our crisis.

He had hope that such awakening could occur. This hope was not the same as naïve optimism. He reckoned realistically on the low odds. But low odds were not zero odds. He retained hope that catastrophe could be avoided. The basis for that hope came in part from the example of certain historical “miracles.” Among these miracles, he noted the fall of the Berlin Wall without a shot being fired and the peaceful collapse of apartheid in South Africa—both seemingly impossible, until they happened. It was that sense of hope in the face of seemingly hopeless odds that kept him going.

I fear there’s not enough time and it’s too late to achieve enough change in enough people. But I’m not going to give up.

If we go down, we’ll go down fighting, helping each other.

His own experience had shown that you should never discount the potential for unexpected consequences. He hoped his release of the Pentagon Papers might help end the war. And so it did—though not in a way he could have foreseen. The Nixon administration, in its obsession to silence him, was not satisfied with indicting him on charges carrying a penalty of 115 years in prison; it set up the illegal “Plumbers” unit to commit a range of crimes against him. When these same Plumbers were later arrested at the Watergate Hotel, Nixon resorted to paying them hush money and committing obstruction of justice to prevent them from revealing their crimes against my father. When this conspiracy was uncovered, not only did it result in the dismissal of the case against him, but ultimately it also forced Nixon’s resignation. That, in turn, effectively ended the war.

You could never know. Nor could you underestimate the power of an act of conscience or truth telling. Randy Kehler, when giving his speech at the conference of the War Resisters International, could not have imagined the impact his words would have on one person sitting in the audience.

As my father liked to say, “Courage is contagious.” We can’t know what we will accomplish, and we might not ever know the results of our actions. Yet in light of what was at stake, the chance of making a difference justified the risk, and at the end of the day, he believed, that was a good way to use your life.

He knew that he was not alone. In one of his last interviews, he said that many people don’t really think or care much about the suffering of people far away, the “others,” those not of their tribe. But there were those who do: the resisters, the peacemakers, the truth tellers. “Those,” he said, “are my tribe.”

What was his counsel for them? Perhaps it is in the last line of these notes:

What can we expect?

Prepare to step into the moment when sudden surprise opportunities for change arise . . .

Knock on doors, many doors, not knowing which may open.

Be ready to drive through.

What was his hope for them? As he wrote in a final letter to his friends and fellow peacemakers: “My wish for you is that at the end of your days you will feel as much joy and gratitude as I do now.”