The Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest in eastern Arizona, where

Mexican gray wolves roam, has proposed a new policy requiring proper

disposal of livestock carcasses - the first time livestock owners would

be tasked with a responsibility to prevent conflicts with wolves.

If the remains of cattle (and sometimes horses and sheep) that have

died of non-wolf causes are not made inedible or removed, they can

attract wolves to prey on live cattle that may be nearby the carcass,

and habituate them to domestic animals instead of their natural prey.

The new policy would effectively ban the practice of baiting wolves

into preying on domestic animals, which can lead to wolves being

trapped or shot by the government in retribution. Such "predator

control" actions are undermining recovery of the Mexican wolf, North

America's most imperiled mammal. The proposed change would help the

beleaguered species recover.

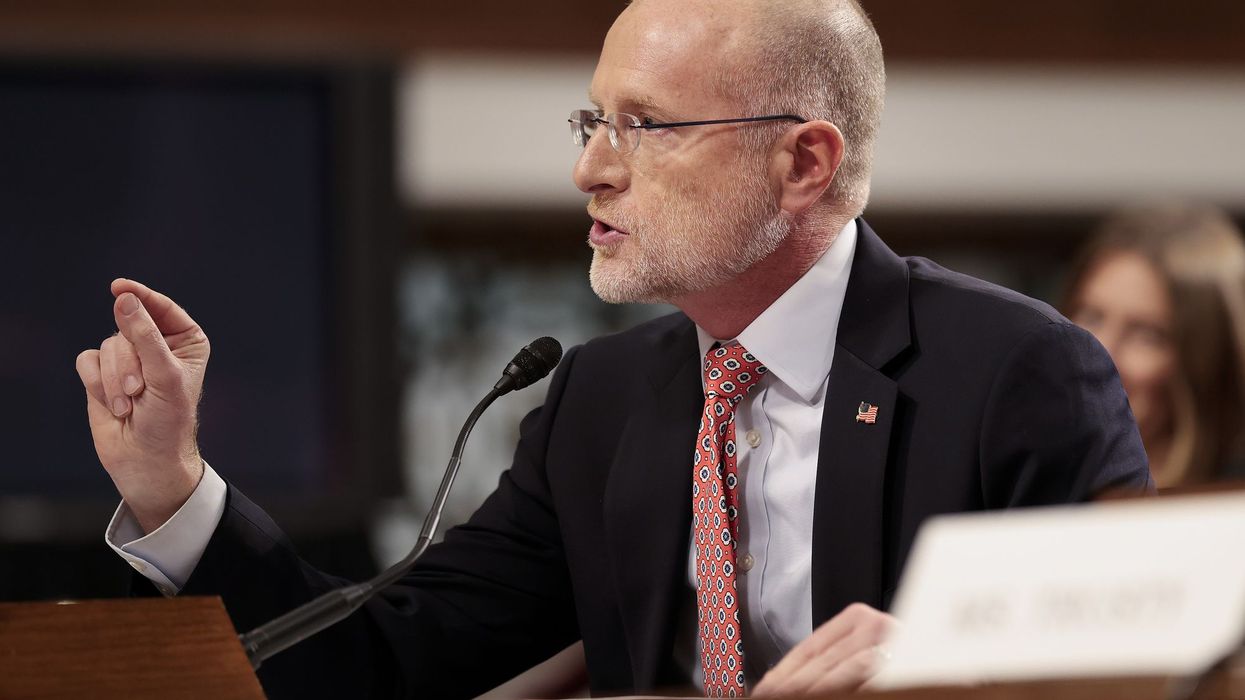

Michael Robinson, a

conservation advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity in

Silver City, N.M., commended the Forest Service for the proposal.

"Ensuring that cattle and horses that die of non-wolf causes don't

entice Mexican wolves into scavenging was recommended by independent

scientists and is just plain common sense," Robinson said.

"If wolves and livestock are to coexist, we must strive to prevent

conflicts rather than blame the wolves once they have already become

used to regarding domestic animals as prey," he said.

The Apache-Sitgreaves is one of several Southwestern national forests

updating their 10-year forest plans, and is the first unit of

government to propose a livestock carcass clean-up policy in the

Southwest. The policy was instituted from the outset of the successful

reintroduction of northern Rocky Mountain gray wolves to Yellowstone

National Park and central Idaho (see background information, below).

Cattle, sheep and horses on public lands die from many causes. During

drought years especially, animals stressed by poor nutrition feed on

poisonous plants. Others forage on steep slopes, from which they fall

to their deaths. Disease, lightning - a surprisingly common cause of death.-

collisions with vehicles, predators, and birth-related deaths also take

a toll. When there is access via roads, the livestock carcasses can be

hauled away or buried. In remote areas, depending on conditions,

carcasses can be made inedible by using corrosive lime, fire or even

dynamite.

The Forest Service's proposal comes in

the form of a line of text in its Draft Desired Conditions for the

Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests' Revised Forest Plan: "Livestock

carcasses are not available for scavenging within the Mexican Wolf

Recovery Zone." (See https://www.fs.fed.us/r3/asnf/plan-revision/documents/ASNF-Draft-DC-2008-08-15.pdf, p. 25.)

The proposal's brevity and informality - there is a Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, but no official recovery "zone" -

belies its significance as a condition to be implemented through new

terms written into livestock grazing permits, once the plan is

finalized.

The Center for Biological Diversity is

requesting that the provision be applied not just in the Apache

National Forest portion of the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, which

consists of the combined Gila and Apache National Forests, but also on

all lands governed by the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests' Revised

Forest Plan. The Sitgreaves National Forest is important wolf habitat

in its own right and could serve as a travel corridor for wolves to

enable them to reach the Grand Canyon ecosystem. Including the

Sitgreaves National Forest would also take into account an ongoing U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service rule-change process intended to allow wolves

to roam beyond the current boundaries.

The Forest Plan Revision Team is inviting public comment on the proposed changes through October 15th via e-mail at: Asnf.planning@fs.fed.us

Background

Several instances have come to light involving Mexican gray wolves that

originally preyed on elk and ignored cows beginning to prey on cows and

ignoring elk after scavenging on already-dead cattle. This was a

problem largely averted in reintroducing northern Rocky Mountain gray

wolves to Yellowstone and Idaho just three years before the

Southwestern wolf-reintroduction program was begun.

The rule governing the 1995 reintroduction of wolves to the northern

Rocky Mountains stated: "If livestock carrion or carcasses are not

being used as bait for an authorized control action on Federal lands,

it must be removed or otherwise disposed of so that they do not attract

wolves." The northern Rockies rule further specified that evidence of

artificial or intentional feeding of wolves would preclude labeling a

wolf in the vicinity a "problem wolf," subject to removal.

But the 1998 rule governing the Mexican gray wolf reintroduction

included no such protections. The regulatory disparity is part of the

reason that, while the northern Rockies now support around 1,450

wolves, the Mexican wolves reintroduced to the Southwest in 1998 number

around 50 animals still in the wild.

The June 2001

Three-Year Review (aka Paquet Report) of the Mexican wolf

reintroduction program, written by a panel of independent scientists

contracted by the Fish and Wildlife Service, advised "Requir[ing]

livestock operators on public land to take some responsibility for

carcass management/disposal to reduce the likelihood that wolves become

habituated to feeding on livestock."

The American

Society of Mammalogists in June 2007 urged "protect[ing] wolves from

the consequences of scavenging on livestock carcasses."

Until now, no government agency would accept responsibility for this.

The Forest Service, which manages the land, has pointed at the Fish and

Wildlife Service as the agency that sets wolf policy. And the Fish and

Wildlife Service defers to a group of six government agencies,

including itself and the Forest Service, which opposes making owners of

stock responsible in any way for preventing scavenging and habituation.

This Catch-22 has been deadly for the wolves.

Despite the abundance of livestock, 88 percent of what the Mexican

wolves eat consists of native ungulates, such as elk and deer, and only

4 percent is livestock (including that which they scavenged but did not

kill), according to the only study on the wolves' diet conducted since

their reintroduction in 1998. But the wolf population is so low and the

rules so draconian that the official responses to even the occasional

livestock depredation serve to thwart recovery.