'A Nation in Decline': Majority of US Public School Students Live in Poverty

Devastating report reveals downward trajectory for today's generation of learners

As it turns out, there's no high-stakes test that can account for this.

A new study released on Friday shows that more than half of students enrolled in U.S. public schools live in poverty, a measurement that the report's authors say places the U.S. on the road to overall social decline.

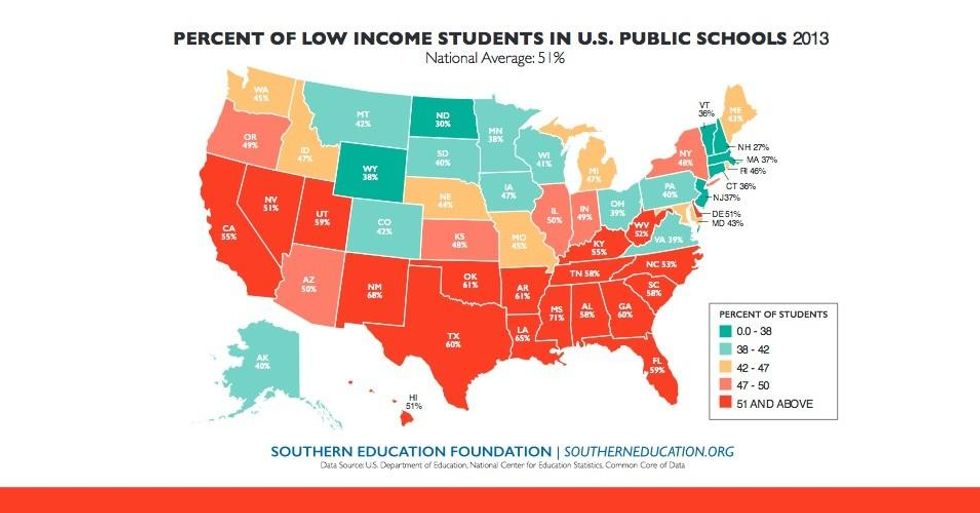

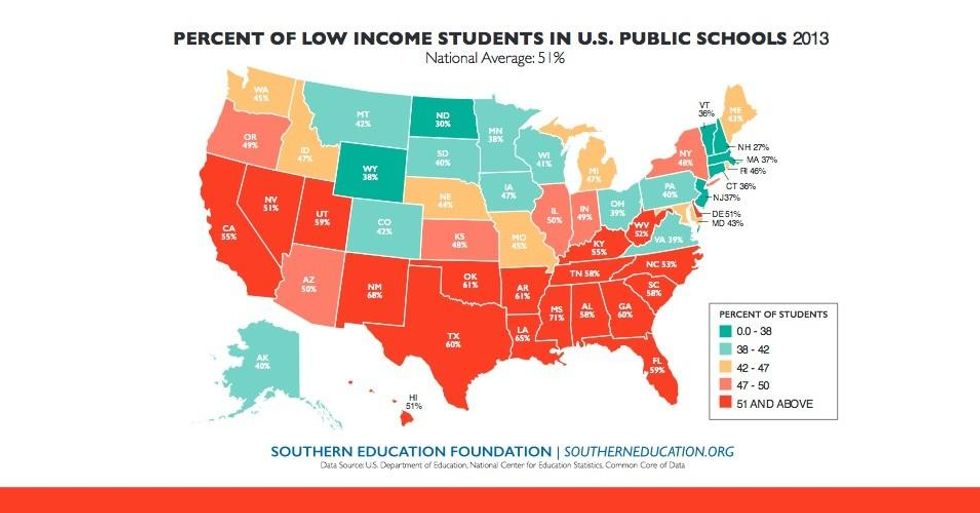

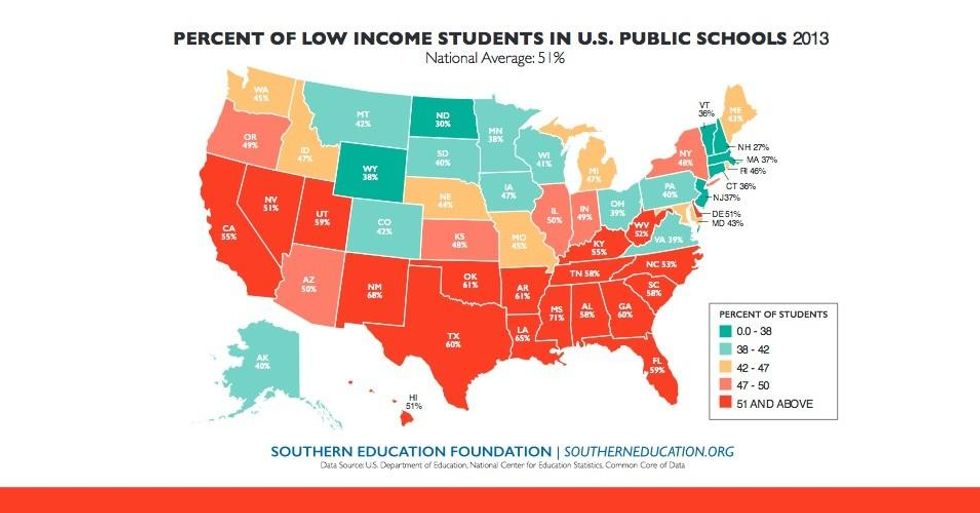

Released by the Southern Education Foundation, the new analysis (pdf) used the most recent national census figures available to confirm that 51 percent of the students across the nation's public schools were low income in 2013.

According to the report:

In 40 of the 50 states, low income students comprised no less than 40 percent of all public schoolchildren. In 21 states, children eligible for free or reduced-price lunches were a majority of the students in 2013.

Most of the states with a majority of low income students are found in the South and the West. Thirteen of the 21 states with a majority of low income students in 2013 were located in the South, and six of the other 21 states were in the West.

Mississippi led the nation with the highest rate: 71 percent, almost three out of every four public school children in Mississippi, were low-income. The nation's second highest rate was found in New Mexico, where 68 percent of all public school students were low income in 2013.

In addition to documenting the number of students who receive some form of government assistance during their school day, including key programs that offer free or reduced-price lunches, the report makes plain that the pervasive poverty among the nation's young people is having a direct and negative impact on student learning and the public education system's ability to meet its goal of providing adequate education for all.

"A lot of people at the top are doing much better, but the people at the bottom are not doing better at all. Those are the people who have the most children and send their children to public school." --Michael Rebell, Campaign for Educational Equity

"No longer can we consider the problems and needs of low income students simply a matter of fairness," the report states. "Their success or failure in the public schools will determine the entire body of human capital and educational potential that the nation will possess in the future. Without improving the educational support that the nation provides its low income students - students with the largest needs and usually with the least support -- the trends of the last decade will be prologue for a nation not at risk, but a nation in decline."

Speaking with the Washington Post, Michael A. Rebell of the Campaign for Educational Equity at Teachers College at Columbia University noted how the poverty rate has been increasing even as some economic indicators have improved. "We've all known this was the trend, that we would get to a majority, but it's here sooner rather than later," Rebell said. "A lot of people at the top are doing much better, but the people at the bottom are not doing better at all. Those are the people who have the most children and send their children to public school."

The latest findings come as the Department of Education and lawmakers in Congress begin new debate about the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ASEA), more broadly known by updated versions or programs supported by that law-- No Child Left Behind (NCLB) under President George W. Bush and the Race To The Top Program (RTTT) under President Obama.

Opponents of the fixation by both Democrats and Republicans on high-stakes standardized testing and other planks of the "corporate education reform agenda" are hoping that ASEA re-authorization is their next opportunity to point out the failure of the policies codified in both NCLB and RTTT.

As Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers, said earlier this week in response to a policy speech by Secretary of Education Arne Duncan: "Any law that doesn't address our biggest challenges--funding inequity, segregation, the effects of poverty--will fail to make the sweeping transformation our kids and our schools need."

She continued, "Current federal educational policy--No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top and waivers--has enshrined a focus on testing, not learning, especially high-stakes testing and the consequences and sanctions that flow from it. That's wrong, and that's why there is a clarion call for change. The waiver strategy and Race to the Top exacerbated the test-fixation that was put in place with NCLB, allowing sanctions and consequences to eclipse all else. [Based on Duncan's speech], it seems the secretary may want to justify and enshrine that status quo and that's worrisome."

In a article for The Nation magazine last year, poverty and education experts Greg Kaufmann and Elaine Weiss described the huge body of research which has shown the various factors associated with how poverty affects student learning, including: "parents' educational attainment; how parents read to, play with and respond to their children; the quality of early care and early education; access to consistent physical and mental health services and healthy food."

What's missing from the larger debate, according to Kaufmann and Weiss, is understanding "the impact of concentrated poverty--and of racial and socioeconomic segregation--on student achievement" in a much wider context. "It's time that we stop ignoring [the impacts of poverty and inequalityon education]," they wrote. "The past few decades have seen increasing income polarization, with the top 1 percent reaping the vast majority of societal gains, the middle class shrinking, and those at the bottom losing ground. As a result, concentrated poverty is more potent and relevant an issue than ever."

And according to an analysis of the SEF findings by Education Week, the increasing levels of poverty among students will, and should be, a larger part of the current debate about education policy:

Schools have, of course, been confronted by the challenges of poverty for years, but crossing the majority threshold certainly creates a powerful conversation point in debates on the local, state, and federal levels about issues ranging from equity and accountability to student supports.

"That deepening poverty likely will complicate already fraught political discussions on how to educate American students, as prior research has shown students are significantly more at risk academically in schools with 40 percent or higher concentrations of poverty," Education Week wrote when it covered growing trends of poverty in 2013.

And, as Rules for Engagement previously reported, poor families are increasingly moving into the suburbs and living in areas with high concentrations of poverty, creating dimensions to the debate.

The new majority of low-income students is yet another new reality for American educators.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As it turns out, there's no high-stakes test that can account for this.

A new study released on Friday shows that more than half of students enrolled in U.S. public schools live in poverty, a measurement that the report's authors say places the U.S. on the road to overall social decline.

Released by the Southern Education Foundation, the new analysis (pdf) used the most recent national census figures available to confirm that 51 percent of the students across the nation's public schools were low income in 2013.

According to the report:

In 40 of the 50 states, low income students comprised no less than 40 percent of all public schoolchildren. In 21 states, children eligible for free or reduced-price lunches were a majority of the students in 2013.

Most of the states with a majority of low income students are found in the South and the West. Thirteen of the 21 states with a majority of low income students in 2013 were located in the South, and six of the other 21 states were in the West.

Mississippi led the nation with the highest rate: 71 percent, almost three out of every four public school children in Mississippi, were low-income. The nation's second highest rate was found in New Mexico, where 68 percent of all public school students were low income in 2013.

In addition to documenting the number of students who receive some form of government assistance during their school day, including key programs that offer free or reduced-price lunches, the report makes plain that the pervasive poverty among the nation's young people is having a direct and negative impact on student learning and the public education system's ability to meet its goal of providing adequate education for all.

"A lot of people at the top are doing much better, but the people at the bottom are not doing better at all. Those are the people who have the most children and send their children to public school." --Michael Rebell, Campaign for Educational Equity

"No longer can we consider the problems and needs of low income students simply a matter of fairness," the report states. "Their success or failure in the public schools will determine the entire body of human capital and educational potential that the nation will possess in the future. Without improving the educational support that the nation provides its low income students - students with the largest needs and usually with the least support -- the trends of the last decade will be prologue for a nation not at risk, but a nation in decline."

Speaking with the Washington Post, Michael A. Rebell of the Campaign for Educational Equity at Teachers College at Columbia University noted how the poverty rate has been increasing even as some economic indicators have improved. "We've all known this was the trend, that we would get to a majority, but it's here sooner rather than later," Rebell said. "A lot of people at the top are doing much better, but the people at the bottom are not doing better at all. Those are the people who have the most children and send their children to public school."

The latest findings come as the Department of Education and lawmakers in Congress begin new debate about the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ASEA), more broadly known by updated versions or programs supported by that law-- No Child Left Behind (NCLB) under President George W. Bush and the Race To The Top Program (RTTT) under President Obama.

Opponents of the fixation by both Democrats and Republicans on high-stakes standardized testing and other planks of the "corporate education reform agenda" are hoping that ASEA re-authorization is their next opportunity to point out the failure of the policies codified in both NCLB and RTTT.

As Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers, said earlier this week in response to a policy speech by Secretary of Education Arne Duncan: "Any law that doesn't address our biggest challenges--funding inequity, segregation, the effects of poverty--will fail to make the sweeping transformation our kids and our schools need."

She continued, "Current federal educational policy--No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top and waivers--has enshrined a focus on testing, not learning, especially high-stakes testing and the consequences and sanctions that flow from it. That's wrong, and that's why there is a clarion call for change. The waiver strategy and Race to the Top exacerbated the test-fixation that was put in place with NCLB, allowing sanctions and consequences to eclipse all else. [Based on Duncan's speech], it seems the secretary may want to justify and enshrine that status quo and that's worrisome."

In a article for The Nation magazine last year, poverty and education experts Greg Kaufmann and Elaine Weiss described the huge body of research which has shown the various factors associated with how poverty affects student learning, including: "parents' educational attainment; how parents read to, play with and respond to their children; the quality of early care and early education; access to consistent physical and mental health services and healthy food."

What's missing from the larger debate, according to Kaufmann and Weiss, is understanding "the impact of concentrated poverty--and of racial and socioeconomic segregation--on student achievement" in a much wider context. "It's time that we stop ignoring [the impacts of poverty and inequalityon education]," they wrote. "The past few decades have seen increasing income polarization, with the top 1 percent reaping the vast majority of societal gains, the middle class shrinking, and those at the bottom losing ground. As a result, concentrated poverty is more potent and relevant an issue than ever."

And according to an analysis of the SEF findings by Education Week, the increasing levels of poverty among students will, and should be, a larger part of the current debate about education policy:

Schools have, of course, been confronted by the challenges of poverty for years, but crossing the majority threshold certainly creates a powerful conversation point in debates on the local, state, and federal levels about issues ranging from equity and accountability to student supports.

"That deepening poverty likely will complicate already fraught political discussions on how to educate American students, as prior research has shown students are significantly more at risk academically in schools with 40 percent or higher concentrations of poverty," Education Week wrote when it covered growing trends of poverty in 2013.

And, as Rules for Engagement previously reported, poor families are increasingly moving into the suburbs and living in areas with high concentrations of poverty, creating dimensions to the debate.

The new majority of low-income students is yet another new reality for American educators.

As it turns out, there's no high-stakes test that can account for this.

A new study released on Friday shows that more than half of students enrolled in U.S. public schools live in poverty, a measurement that the report's authors say places the U.S. on the road to overall social decline.

Released by the Southern Education Foundation, the new analysis (pdf) used the most recent national census figures available to confirm that 51 percent of the students across the nation's public schools were low income in 2013.

According to the report:

In 40 of the 50 states, low income students comprised no less than 40 percent of all public schoolchildren. In 21 states, children eligible for free or reduced-price lunches were a majority of the students in 2013.

Most of the states with a majority of low income students are found in the South and the West. Thirteen of the 21 states with a majority of low income students in 2013 were located in the South, and six of the other 21 states were in the West.

Mississippi led the nation with the highest rate: 71 percent, almost three out of every four public school children in Mississippi, were low-income. The nation's second highest rate was found in New Mexico, where 68 percent of all public school students were low income in 2013.

In addition to documenting the number of students who receive some form of government assistance during their school day, including key programs that offer free or reduced-price lunches, the report makes plain that the pervasive poverty among the nation's young people is having a direct and negative impact on student learning and the public education system's ability to meet its goal of providing adequate education for all.

"A lot of people at the top are doing much better, but the people at the bottom are not doing better at all. Those are the people who have the most children and send their children to public school." --Michael Rebell, Campaign for Educational Equity

"No longer can we consider the problems and needs of low income students simply a matter of fairness," the report states. "Their success or failure in the public schools will determine the entire body of human capital and educational potential that the nation will possess in the future. Without improving the educational support that the nation provides its low income students - students with the largest needs and usually with the least support -- the trends of the last decade will be prologue for a nation not at risk, but a nation in decline."

Speaking with the Washington Post, Michael A. Rebell of the Campaign for Educational Equity at Teachers College at Columbia University noted how the poverty rate has been increasing even as some economic indicators have improved. "We've all known this was the trend, that we would get to a majority, but it's here sooner rather than later," Rebell said. "A lot of people at the top are doing much better, but the people at the bottom are not doing better at all. Those are the people who have the most children and send their children to public school."

The latest findings come as the Department of Education and lawmakers in Congress begin new debate about the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ASEA), more broadly known by updated versions or programs supported by that law-- No Child Left Behind (NCLB) under President George W. Bush and the Race To The Top Program (RTTT) under President Obama.

Opponents of the fixation by both Democrats and Republicans on high-stakes standardized testing and other planks of the "corporate education reform agenda" are hoping that ASEA re-authorization is their next opportunity to point out the failure of the policies codified in both NCLB and RTTT.

As Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers, said earlier this week in response to a policy speech by Secretary of Education Arne Duncan: "Any law that doesn't address our biggest challenges--funding inequity, segregation, the effects of poverty--will fail to make the sweeping transformation our kids and our schools need."

She continued, "Current federal educational policy--No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top and waivers--has enshrined a focus on testing, not learning, especially high-stakes testing and the consequences and sanctions that flow from it. That's wrong, and that's why there is a clarion call for change. The waiver strategy and Race to the Top exacerbated the test-fixation that was put in place with NCLB, allowing sanctions and consequences to eclipse all else. [Based on Duncan's speech], it seems the secretary may want to justify and enshrine that status quo and that's worrisome."

In a article for The Nation magazine last year, poverty and education experts Greg Kaufmann and Elaine Weiss described the huge body of research which has shown the various factors associated with how poverty affects student learning, including: "parents' educational attainment; how parents read to, play with and respond to their children; the quality of early care and early education; access to consistent physical and mental health services and healthy food."

What's missing from the larger debate, according to Kaufmann and Weiss, is understanding "the impact of concentrated poverty--and of racial and socioeconomic segregation--on student achievement" in a much wider context. "It's time that we stop ignoring [the impacts of poverty and inequalityon education]," they wrote. "The past few decades have seen increasing income polarization, with the top 1 percent reaping the vast majority of societal gains, the middle class shrinking, and those at the bottom losing ground. As a result, concentrated poverty is more potent and relevant an issue than ever."

And according to an analysis of the SEF findings by Education Week, the increasing levels of poverty among students will, and should be, a larger part of the current debate about education policy:

Schools have, of course, been confronted by the challenges of poverty for years, but crossing the majority threshold certainly creates a powerful conversation point in debates on the local, state, and federal levels about issues ranging from equity and accountability to student supports.

"That deepening poverty likely will complicate already fraught political discussions on how to educate American students, as prior research has shown students are significantly more at risk academically in schools with 40 percent or higher concentrations of poverty," Education Week wrote when it covered growing trends of poverty in 2013.

And, as Rules for Engagement previously reported, poor families are increasingly moving into the suburbs and living in areas with high concentrations of poverty, creating dimensions to the debate.

The new majority of low-income students is yet another new reality for American educators.