As Planet Warms, One of World's Deadliest Diseases Could Spread

Report shows that warming temperatures linked to spread of malaria to population centers in Colombia and Ethiopia

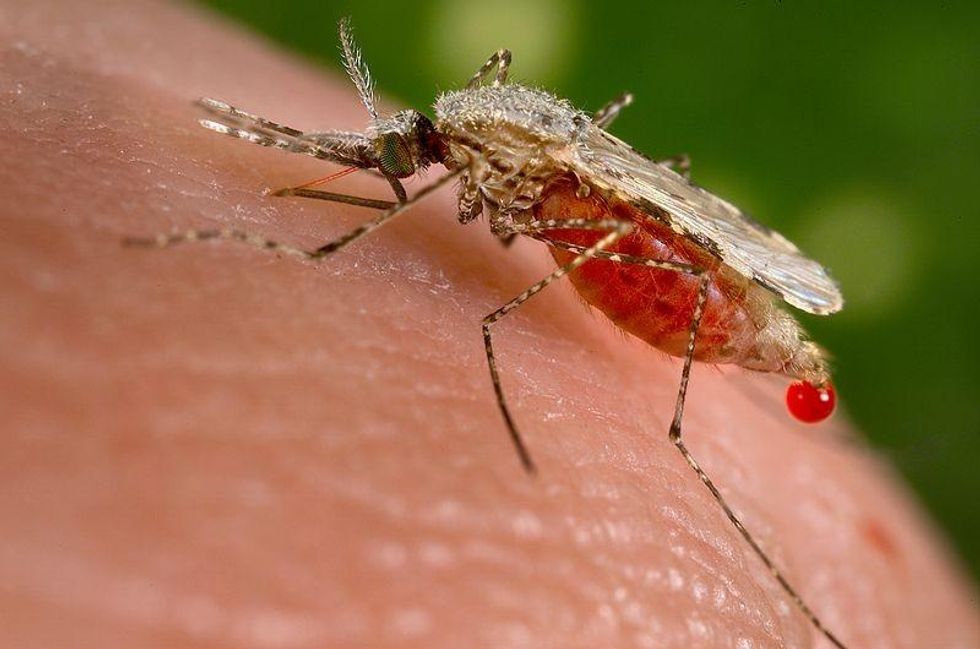

The mosquito-borne disease already disproportionately affects poor and rural communities in the global south, killing approximately 1.2 million people a year, hitting sub-Saharan Africa the hardest. Researchers from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and University of Michigan report in the journal Science that they are the first to uncover evidence that changes in climate push this disease to higher elevations -- an outcome that is not good for humans.

Analyzing records of malaria cases in the Antioquia region of western Colombia between 1990 to 2005, as well as from the Debre Zeit area of central Ethiopia from 1993 to 2005, researchers uncovered evidence that malaria moves to higher altitudes during warmer temperatures and lower altitudes during cooler temperatures. The researchers accounted for other factors, such as drug resistance, rain patterns, and mosquito control programs.

These higher elevation areas are more densely-populated, in part because many highland cities emerged to avoid malaria, according to Menno Bouma, a co-author and a lecturer at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, referenced in Scientific American. In Ethiopia, for example, 43 percent of the population -- approximately 37 million people -- live at higher elevations between 1,600 and 2,400 meters.

The study "suggests that with progressive global warming, malaria will creep up the mountains and spread to new high-altitude areas," said Boum, according to Reuters. Due to the lower exposure of these population, people living at higher elevations have lower immunity, the study notes.

The findings are limited to Colombia and Ethiopia, and the researchers say that more areas must be studied before broad trends are identified. Yet the report authors argue that these local findings imply that malaria infections will rise as the global temperature does. Says Bouma, "If you have a [disease range] contraction due to temperature increases in the drier parts of the world and an increase in the cooler parts of the world, the population affected in the cooler ends of the malaria distribution would be larger."

_____________________

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

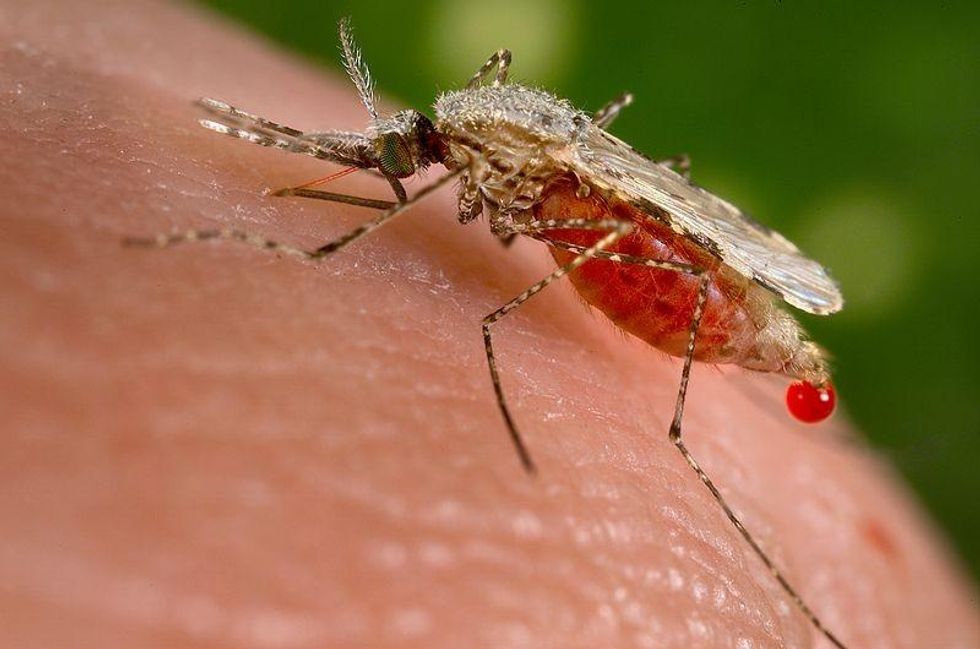

The mosquito-borne disease already disproportionately affects poor and rural communities in the global south, killing approximately 1.2 million people a year, hitting sub-Saharan Africa the hardest. Researchers from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and University of Michigan report in the journal Science that they are the first to uncover evidence that changes in climate push this disease to higher elevations -- an outcome that is not good for humans.

Analyzing records of malaria cases in the Antioquia region of western Colombia between 1990 to 2005, as well as from the Debre Zeit area of central Ethiopia from 1993 to 2005, researchers uncovered evidence that malaria moves to higher altitudes during warmer temperatures and lower altitudes during cooler temperatures. The researchers accounted for other factors, such as drug resistance, rain patterns, and mosquito control programs.

These higher elevation areas are more densely-populated, in part because many highland cities emerged to avoid malaria, according to Menno Bouma, a co-author and a lecturer at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, referenced in Scientific American. In Ethiopia, for example, 43 percent of the population -- approximately 37 million people -- live at higher elevations between 1,600 and 2,400 meters.

The study "suggests that with progressive global warming, malaria will creep up the mountains and spread to new high-altitude areas," said Boum, according to Reuters. Due to the lower exposure of these population, people living at higher elevations have lower immunity, the study notes.

The findings are limited to Colombia and Ethiopia, and the researchers say that more areas must be studied before broad trends are identified. Yet the report authors argue that these local findings imply that malaria infections will rise as the global temperature does. Says Bouma, "If you have a [disease range] contraction due to temperature increases in the drier parts of the world and an increase in the cooler parts of the world, the population affected in the cooler ends of the malaria distribution would be larger."

_____________________

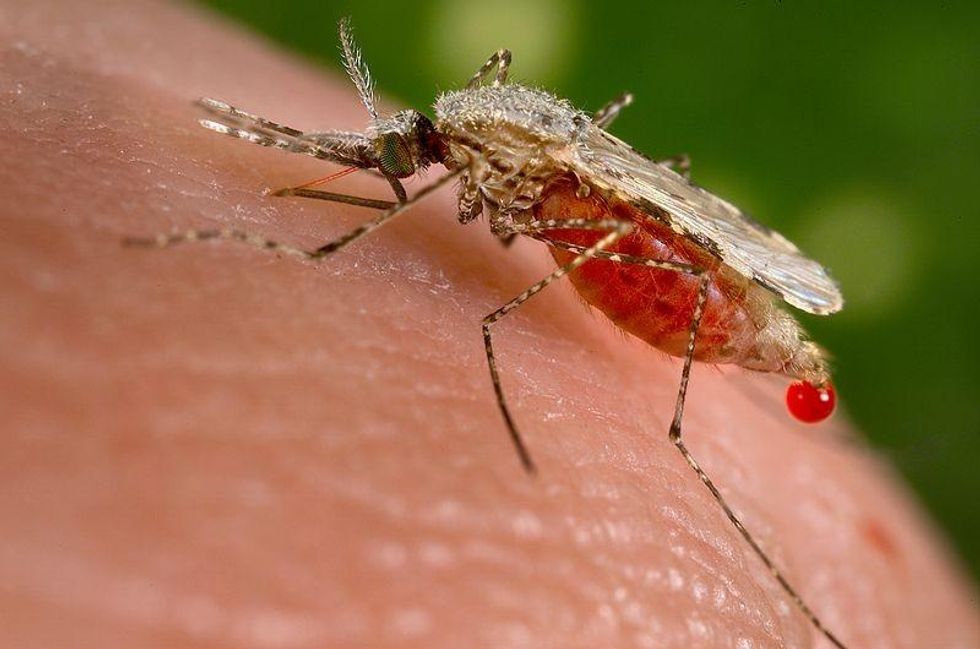

The mosquito-borne disease already disproportionately affects poor and rural communities in the global south, killing approximately 1.2 million people a year, hitting sub-Saharan Africa the hardest. Researchers from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and University of Michigan report in the journal Science that they are the first to uncover evidence that changes in climate push this disease to higher elevations -- an outcome that is not good for humans.

Analyzing records of malaria cases in the Antioquia region of western Colombia between 1990 to 2005, as well as from the Debre Zeit area of central Ethiopia from 1993 to 2005, researchers uncovered evidence that malaria moves to higher altitudes during warmer temperatures and lower altitudes during cooler temperatures. The researchers accounted for other factors, such as drug resistance, rain patterns, and mosquito control programs.

These higher elevation areas are more densely-populated, in part because many highland cities emerged to avoid malaria, according to Menno Bouma, a co-author and a lecturer at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, referenced in Scientific American. In Ethiopia, for example, 43 percent of the population -- approximately 37 million people -- live at higher elevations between 1,600 and 2,400 meters.

The study "suggests that with progressive global warming, malaria will creep up the mountains and spread to new high-altitude areas," said Boum, according to Reuters. Due to the lower exposure of these population, people living at higher elevations have lower immunity, the study notes.

The findings are limited to Colombia and Ethiopia, and the researchers say that more areas must be studied before broad trends are identified. Yet the report authors argue that these local findings imply that malaria infections will rise as the global temperature does. Says Bouma, "If you have a [disease range] contraction due to temperature increases in the drier parts of the world and an increase in the cooler parts of the world, the population affected in the cooler ends of the malaria distribution would be larger."

_____________________