Worldwide Demand for Water Outstrips Supply: Study

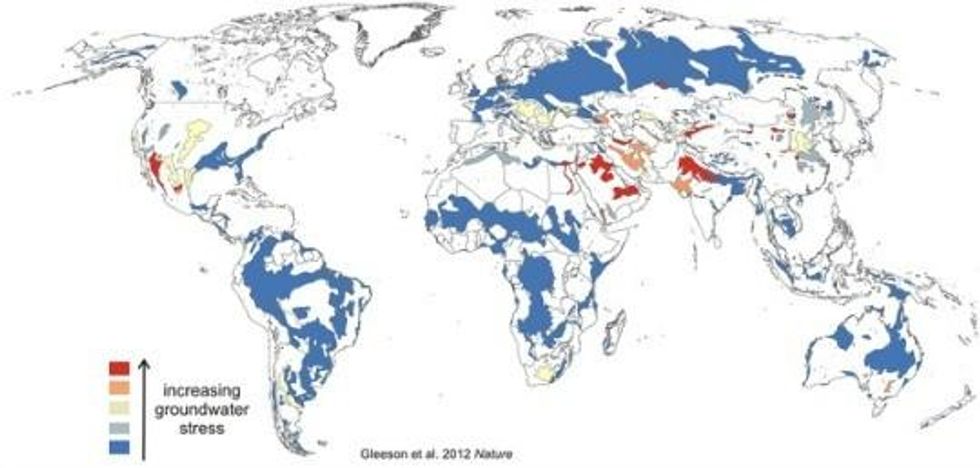

Groundwater use is unsustainable in many of the world's major agricultural zones

The world's oldest and largest acquifers, according to the study, have supplied civilization with water for agricultural and industrial use for thousands of years, but are now under threat from over-extraction and the underground reservoirs can no longer replenish themselves at a sustainable rate.

"This overuse can lead to decreased groundwater availability for both drinking water and growing food," says Tom Gleeson, a hydrogeologist at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, and lead author of the study. Eventually, he adds, it "can lead to dried up streams and ecological impacts".

Gleeson said irrigation for agriculture drives much of the demand and is the main driver for the fragility of the acquifers. According to the study, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Mexico, and the United States lead the global pack of water-thirsty nations.

The researchers, from McGill University in Montreal and Utrecht University in the Netherlands, combined groundwater usage data from around the globe with computer models of underground water resources to come up with a measure of water usage relative to supply.

In addition, the scientists calculated how much stress each source of groundwater is under and looked in detail at the water flows needed to sustain the health of ecosystems such as grasses, trees and streams.

"To my knowledge, this is the first water-stress index that actually accounts for preserving the health of the environment," says Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the study. "That's a critical step."

According to Reuters, "Gleeson said limits on water extraction, more efficient irrigation and the promotion of different diets, with less or no meat, could make these water resources more sustainable."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

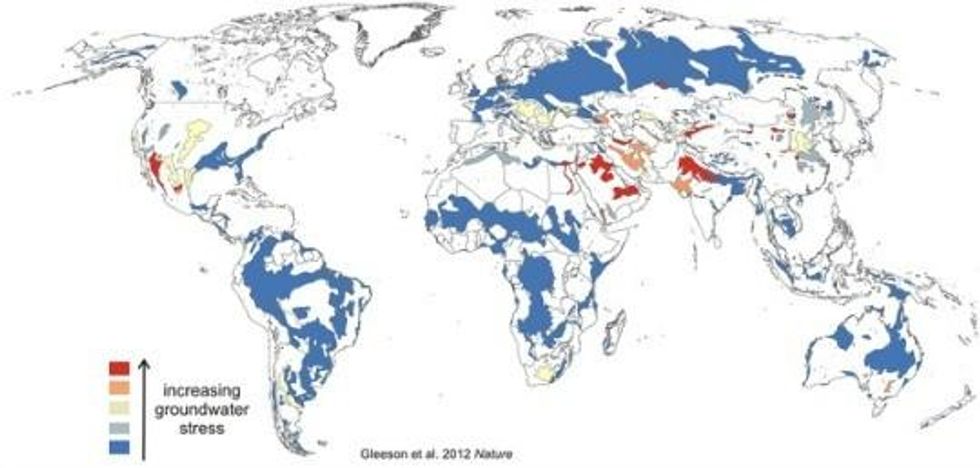

The world's oldest and largest acquifers, according to the study, have supplied civilization with water for agricultural and industrial use for thousands of years, but are now under threat from over-extraction and the underground reservoirs can no longer replenish themselves at a sustainable rate.

"This overuse can lead to decreased groundwater availability for both drinking water and growing food," says Tom Gleeson, a hydrogeologist at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, and lead author of the study. Eventually, he adds, it "can lead to dried up streams and ecological impacts".

Gleeson said irrigation for agriculture drives much of the demand and is the main driver for the fragility of the acquifers. According to the study, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Mexico, and the United States lead the global pack of water-thirsty nations.

The researchers, from McGill University in Montreal and Utrecht University in the Netherlands, combined groundwater usage data from around the globe with computer models of underground water resources to come up with a measure of water usage relative to supply.

In addition, the scientists calculated how much stress each source of groundwater is under and looked in detail at the water flows needed to sustain the health of ecosystems such as grasses, trees and streams.

"To my knowledge, this is the first water-stress index that actually accounts for preserving the health of the environment," says Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the study. "That's a critical step."

According to Reuters, "Gleeson said limits on water extraction, more efficient irrigation and the promotion of different diets, with less or no meat, could make these water resources more sustainable."

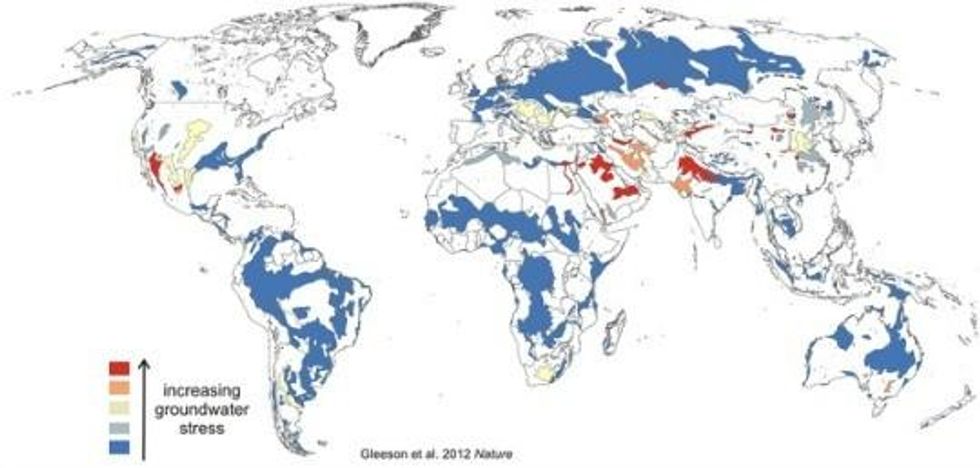

The world's oldest and largest acquifers, according to the study, have supplied civilization with water for agricultural and industrial use for thousands of years, but are now under threat from over-extraction and the underground reservoirs can no longer replenish themselves at a sustainable rate.

"This overuse can lead to decreased groundwater availability for both drinking water and growing food," says Tom Gleeson, a hydrogeologist at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, and lead author of the study. Eventually, he adds, it "can lead to dried up streams and ecological impacts".

Gleeson said irrigation for agriculture drives much of the demand and is the main driver for the fragility of the acquifers. According to the study, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Mexico, and the United States lead the global pack of water-thirsty nations.

The researchers, from McGill University in Montreal and Utrecht University in the Netherlands, combined groundwater usage data from around the globe with computer models of underground water resources to come up with a measure of water usage relative to supply.

In addition, the scientists calculated how much stress each source of groundwater is under and looked in detail at the water flows needed to sustain the health of ecosystems such as grasses, trees and streams.

"To my knowledge, this is the first water-stress index that actually accounts for preserving the health of the environment," says Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the study. "That's a critical step."

According to Reuters, "Gleeson said limits on water extraction, more efficient irrigation and the promotion of different diets, with less or no meat, could make these water resources more sustainable."