WASHINGTON - From the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the United Nations, to Interpol and the World Health Organization (WHO), dozens of international agencies now work to regulate world trade, telecommunications, transportation, labor, business, health and the environment, among other issues.

In almost all of those bodies, poor and powerless nations, like Somalia and Afghanistan, are under-represented while the rich and powerful, like Britain and the United States, operate with almost unchecked authority and overwhelming power.

Some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are impatient to see real change.

''We talk about democratic and accountable organizations so we could live in a truly global community, where a country like the United States, instead of boasting of being a superpower, becomes a true part of the global community,'' says Anuradha Mittal, co-director of California-based Food First, a group that has called for the rule of law in global bodies.

''We are talking about that multilateral system of checks and balances, when countries like Sudan and India, or countries like the United States, all adhere to the same principles.''

That is unlikely under the current structures of those institutions. At the United Nations, the mother of all agencies and one of the most respected worldwide, the 15-member Security Council, the only international body with powers to declare war and peace, is a stark example of global inequality.

The council is heavily weighted in favor of the five big powers - the United States, Britain, France, China and Russia - which all exercise veto power over its decisions.

Although the 191-member New York-based U.N. General Assembly works on the principle of one-country, one-vote, the Security Council is almost at the mercy of the five veto-wielding powers, except in those instances when they themselves disagree, as in the recent debate over using force in Iraq.

The democratic discrepancy also infests economic institutions. At the Washington-based International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, seats and votes are still allocated according to member countries' economic bulk, leaving poor nations defenseless before heavyweight nations like the United States and Japan.

The Bank and the Fund each have 184 members, including developed and developing countries, and 24 board members representing countries or groups of nations.

But while the 46 sub-Saharan African countries, for example, are represented by only two executive directors on the boards of the Bank and Fund, eight rich nations, including Germany, France, Britain and the United States, are represented by their own executive directors.

Directors from rich countries now control more than 60 per cent of the votes at the World Bank and IMF, while the U.S. administration has veto power over any extraordinary vote requiring a super-majority.

Even in institutions like the Geneva-based WTO, which theoretically operates under consensus and technically gives each member country veto power, practice is different.

Some 28 of the WTO's 146 member nations do not even attend most of the organization's meetings for the simple reason that they lack the resources to set up diplomatic missions in the expensive Swiss city of Geneva. But those countries still figure as part of the consensus when decisions are made.

And while the WTO system is set up so that all members participate in preliminary discussions and decision-making meetings, in practice negotiations are limited to select groups of countries, known as "green rooms", often hand picked to include the European Union, the United States, and Japan.

In several cases, the system "has operated against the interests of the developing countries", says Bhagirath Lal Das, India's former chief negotiator under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).

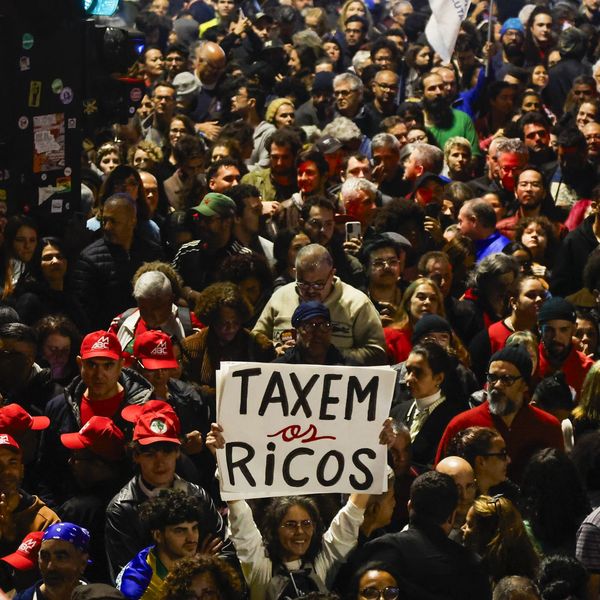

The list of ''unbalanced'' institutions that are supposed to represent all parts of the world equally is lengthy, as noted by the anti-globalization movement, which has vigorously raised the issues of transparency, democracy and accountability using colorful marches, street protests and public events.

Civil society groups have noted that attempts aimed at redressing such balances have been largely futile and often meet with strong resistance from the beneficiaries of the status quo.

Over the last 10 years, a U.N. working group has been discussing proposals to restructure the Security Council with the aim of providing equitable representation to the world's developing nations, who comprise over two-thirds of the membership of the world body.

The proposals include veto power status to developing nations from Asia, Africa and Latin America. The veto contenders include India and Indonesia from Asia; Mexico, Argentina and Brazil from Latin America; and South Africa, Nigeria and Egypt from Africa.

But the working group has remained deadlocked and unable to devise a compromise formula to make the Council more representative of the United Nations.

The deadlock has been caused both by opposition from Western powers to an enlarged Security Council and to the abolition of veto powers, and by divisions among developing nations as to which of them should sit on the restructured body.

In April, a renewed drive to give developing countries more say in running the IMF and the World Bank, two agencies accused of drowning poor nations in poverty and debt, netted only lip service from rich nations and promises to keep the issue alive for future consideration.

At the WTO, despite pressure from civil society groups, Washington in December brushed aside criticism and exercised its power when it blocked a decision that could have backed developing countries' right to access low-cost medications.

''This is exactly what we want to see go,'' said Mittal. ''That this 'who has the gold, has the law' is a mentality that has to go. That mentality of the superpower has to go. Nobody should be above the law.''

With reporting by Thalif Deen at the United Nations and Gustavo Capdevila in Geneva.