Rosa Parks, Now and Forever

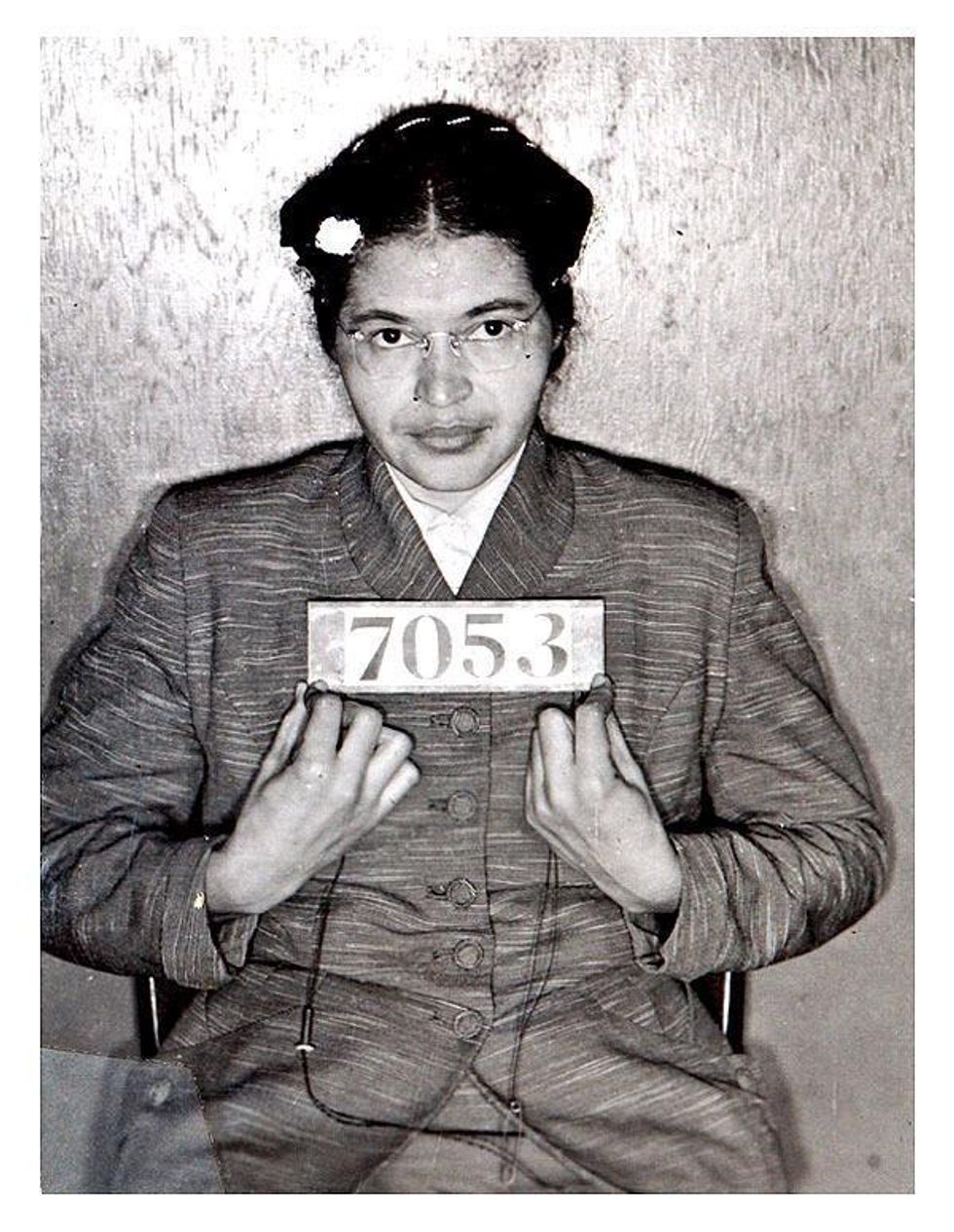

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger in Montgomery, Ala., thus launching the modern-day civil-rights movement. Monday, Feb. 4, is the 100th anniversary of her birth. After she died at the age of 92 in 2005, much of the media described her as a tired seamstress, no troublemaker. But the media got it wrong.

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger in Montgomery, Ala., thus

Professor Jeanne Theoharis debunks the myth of the quiet seamstress in her new book "The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks." Theoharis told me, "This is the story of a life history of activism, a life history that she would put it, as being 'rebellious,' that starts decades before her famous bus stand and ends decades after."

She was born in Tuskegee, Ala., and raised to believe that she had a right to be respected, and to demand that respect. Jim Crow laws were entrenched then, and segregation was violently enforced. In Pine Level, where she lived, white children got a bus ride to school, while African-American children walked. Rosa Parks recalled: "But to me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world."

In her late teens, Rosa met Raymond Parks, and they married. Rosa described Raymond Parks as the first activist she had ever met. He was a member of the local Montgomery NAACP chapter, and, when she learned that women were welcome at the meetings, she attended. She was elected the chapter's secretary.

It was there that Rosa met and worked with E.D. Nixon, a radical labor organizer. Rosa Parks was able to attend the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, in 1955. The school was a gathering place for activists--black and white together--committed to overcoming segregation, and for developing strategies and tactics for nonviolent resistance to it. It was there that Pete Seeger and others wrote the song "We Shall Overcome" as the enduring anthem of the civil-rights movement.

When she met Nelson Mandela after his release from prison, he told her, "You sustained me while I was in prison all those years."

When Rosa Parks died, she was the first African-American woman to lie in state in the Capitol rotunda. I raced down to Washington, D.C., to cover her memorial service. I met a young college student and asked her why she was there standing outside with so many hundreds of people listening to the service on loudspeakers. She said proudly, "I emailed my professors and said I won't be in class today; I'm going to get an education."

Rosa Parks has much to teach us. In fact, she and other young women had refused to give up their seats on the bus before Dec. 1, 1955. You never know when that magic moment will come. This Feb. 4, the U.S. Postal Service will release a Rosa Parks Forever stamp, a reminder of the enduring mark she made. Rosa Parks was no tired seamstress. As she said of that brave action she took, "The only tired I was, was tired of giving in."

Denis Moynihan contributed research to this column.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger in Montgomery, Ala., thus

Professor Jeanne Theoharis debunks the myth of the quiet seamstress in her new book "The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks." Theoharis told me, "This is the story of a life history of activism, a life history that she would put it, as being 'rebellious,' that starts decades before her famous bus stand and ends decades after."

She was born in Tuskegee, Ala., and raised to believe that she had a right to be respected, and to demand that respect. Jim Crow laws were entrenched then, and segregation was violently enforced. In Pine Level, where she lived, white children got a bus ride to school, while African-American children walked. Rosa Parks recalled: "But to me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world."

In her late teens, Rosa met Raymond Parks, and they married. Rosa described Raymond Parks as the first activist she had ever met. He was a member of the local Montgomery NAACP chapter, and, when she learned that women were welcome at the meetings, she attended. She was elected the chapter's secretary.

It was there that Rosa met and worked with E.D. Nixon, a radical labor organizer. Rosa Parks was able to attend the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, in 1955. The school was a gathering place for activists--black and white together--committed to overcoming segregation, and for developing strategies and tactics for nonviolent resistance to it. It was there that Pete Seeger and others wrote the song "We Shall Overcome" as the enduring anthem of the civil-rights movement.

When she met Nelson Mandela after his release from prison, he told her, "You sustained me while I was in prison all those years."

When Rosa Parks died, she was the first African-American woman to lie in state in the Capitol rotunda. I raced down to Washington, D.C., to cover her memorial service. I met a young college student and asked her why she was there standing outside with so many hundreds of people listening to the service on loudspeakers. She said proudly, "I emailed my professors and said I won't be in class today; I'm going to get an education."

Rosa Parks has much to teach us. In fact, she and other young women had refused to give up their seats on the bus before Dec. 1, 1955. You never know when that magic moment will come. This Feb. 4, the U.S. Postal Service will release a Rosa Parks Forever stamp, a reminder of the enduring mark she made. Rosa Parks was no tired seamstress. As she said of that brave action she took, "The only tired I was, was tired of giving in."

Denis Moynihan contributed research to this column.

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger in Montgomery, Ala., thus

Professor Jeanne Theoharis debunks the myth of the quiet seamstress in her new book "The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks." Theoharis told me, "This is the story of a life history of activism, a life history that she would put it, as being 'rebellious,' that starts decades before her famous bus stand and ends decades after."

She was born in Tuskegee, Ala., and raised to believe that she had a right to be respected, and to demand that respect. Jim Crow laws were entrenched then, and segregation was violently enforced. In Pine Level, where she lived, white children got a bus ride to school, while African-American children walked. Rosa Parks recalled: "But to me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world."

In her late teens, Rosa met Raymond Parks, and they married. Rosa described Raymond Parks as the first activist she had ever met. He was a member of the local Montgomery NAACP chapter, and, when she learned that women were welcome at the meetings, she attended. She was elected the chapter's secretary.

It was there that Rosa met and worked with E.D. Nixon, a radical labor organizer. Rosa Parks was able to attend the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, in 1955. The school was a gathering place for activists--black and white together--committed to overcoming segregation, and for developing strategies and tactics for nonviolent resistance to it. It was there that Pete Seeger and others wrote the song "We Shall Overcome" as the enduring anthem of the civil-rights movement.

When she met Nelson Mandela after his release from prison, he told her, "You sustained me while I was in prison all those years."

When Rosa Parks died, she was the first African-American woman to lie in state in the Capitol rotunda. I raced down to Washington, D.C., to cover her memorial service. I met a young college student and asked her why she was there standing outside with so many hundreds of people listening to the service on loudspeakers. She said proudly, "I emailed my professors and said I won't be in class today; I'm going to get an education."

Rosa Parks has much to teach us. In fact, she and other young women had refused to give up their seats on the bus before Dec. 1, 1955. You never know when that magic moment will come. This Feb. 4, the U.S. Postal Service will release a Rosa Parks Forever stamp, a reminder of the enduring mark she made. Rosa Parks was no tired seamstress. As she said of that brave action she took, "The only tired I was, was tired of giving in."

Denis Moynihan contributed research to this column.