SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"But, Yossarian, suppose everyone felt that way."

"Then," said Yossarian, "I'd certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way, wouldn't I?" --Joseph Heller, Catch-22

Last November 29, American Airlines declared bankruptcy under Chapter 11, the provision of the bankruptcy code that allows a corporation to stiff its creditors, break contracts, and keep operating under the supervision of a judge. This maneuver, politely termed a "reorganization," ends with the corporation exiting bankruptcy cleansed of old debts. In opting for Chapter 11, American joined every other major airline, including Delta, Northwest, United, and US Airways, which has been in and out of Chapter 11 twice since 2002. No fewer than 189 airlines have declared bankruptcy since 1990. As the sole large carrier that had not gone bankrupt, American missed out on savings available to its rivals and thus was increasingly uncompetitive.

Bankruptcy is intended to give a fresh start to persons and enterprises overwhelmed by creditors. In the case of American (like other airlines before it), the main "creditors" are its employees. The costs of American's bankruptcy will be borne mainly by its workers and secondarily by taxpayers. The contracts being broken are union contracts and legal promises to honor pension obligations. American is laying off 13,000 workers, slashing wages, and reducing its annual pension contribution from $97 million to $6.5 million. The airline hopes to stick the federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation with liability for much of the $6.5 billion that it owes its workers and retirees.

This national indulgence for corporate bankruptcy has a certain logic. The Wall Street Journal editorial page recently termed bankruptcy "one of the better ways in which American capitalism encourages risk-taking," and that is the prevailing view. Thanks to Chapter 11, a potentially viable insolvent enterprise is given a fresh start as a going concern, rather than being cannibalized for the benefit of its creditors.

However, what's good for corporate capitalism is evidently too good for the rest of us. Suppose everyone felt that way?

Wall Street has convinced lawmakers that relief for the masses, even in a deflationary economic emergency, would not only inflict unacceptable costs to bank balance sheets; it would also promote "moral hazard"--the economist's term for rewarding and thereby inviting improvident behavior. Thanks to a revision in the bankruptcy law passed in 2005 and signed by President George W. Bush after nearly a decade of furious lobbying by the credit-card industry and the banks, consumers generally face far more onerous bankruptcy terms than do corporations.

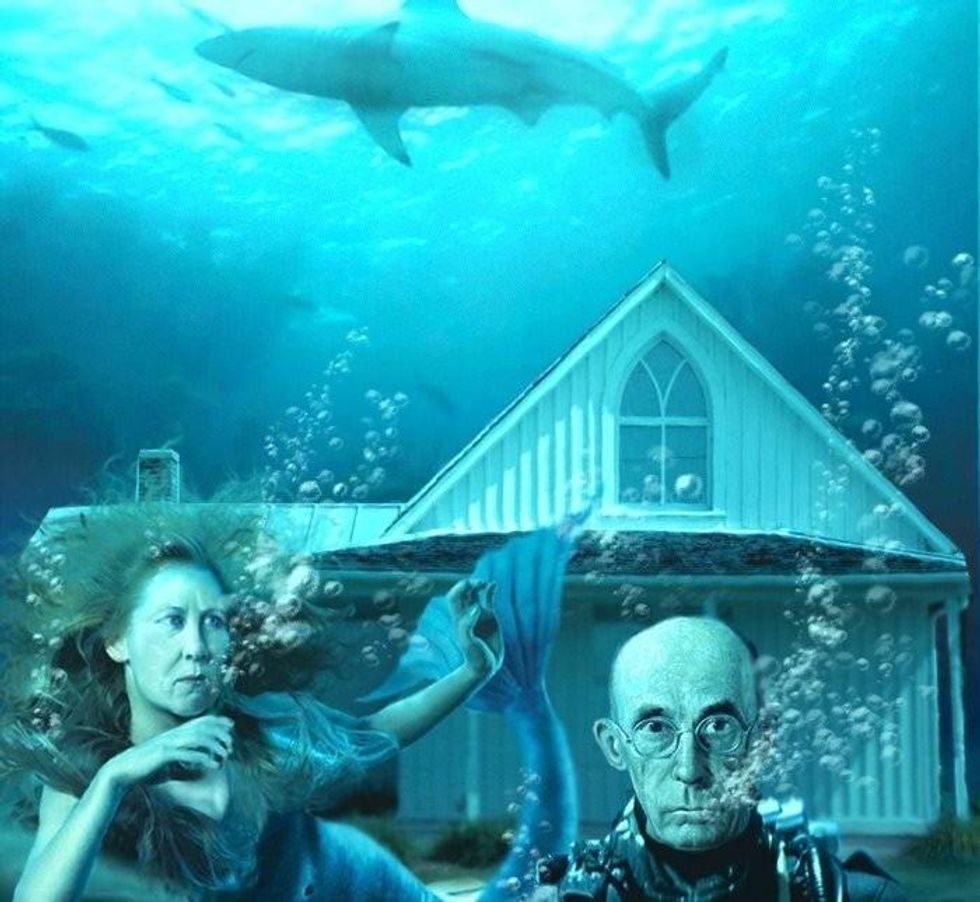

The housing collapse, depressing trillions of dollars of consumer assets, is the single biggest drag on the recovery. But underwater mortgage holders, unlike submerged corporations, have never been eligible for bankruptcy relief. Homeowners are explicitly prohibited from using the bankruptcy code to reduce the amount of the mortgage to the present value of the house or to a monthly payment that could enable them to keep their home.

The selective privileges of bankruptcy display yet another facet of the convenient concept of corporate personhood. Some persons are evidently more equal than others. The gross disparity in the way that bankruptcy law treats corporate persons and actual people is only one of multiple double standards that increasingly define our age.

Petty felons and 200,000 small-time drug users do prison time, while corporate criminals whose frauds cost the rest of the economy trillions of dollars are permitted to settle civil suits for small fines, with shareholders bearing the expenses. Ordinary families pay tax at a higher rate than billionaires. When fracking contaminates a property and makes a home uninhabitable, the homeowner rather than the natural-gas company suffers the loss. The mother of all double standards is taxpayer aid and Federal Reserve advances--running into the trillions of dollars--that went to the banks that caused the collapse, while the bankers avoided prosecution, and the rest of the society got to eat austerity.

Linking all of these disparities between citizens and corporations is the political power of a new American plutocracy. Until our politics connects these dots and citizens start resisting, the financial elite will rule. Despite the Occupy movement, most regular people have yet to experience the sudden enlightenment of Captain Yossarian, who decided, unpatriotically, that he didn't want to die. In the face of economic pillaging, we are behaving like damned fools.

Bankruptcy privileges for the elite have been with us for centuries. On October 29, 1692, Daniel Defoe, merchant, pamphleteer, and the future best-selling author of Robinson Crusoe, was committed to London's King's Bench Prison because he could not pay debts that totaled some 17,000 pounds. Before Defoe was declared bankrupt, his far-flung ventures had included underwriting marine insurance, importing wine from Portugal, buying a diving bell to search for buried treasure, and investing in 70 civet cats whose musk secretions were prized for the manufacture of perfume.

In that era, there was no Chapter 11. Bankrupts like Defoe ended up in debtors prison, an institution that would persist well into the 19th century. Typically, creditors could obtain a writ of seizure of the debtor's assets (historians record that Defoe's civet cats were taken by the sheriff's men); if the assets were insufficient to settle the debt, another writ would send the bankrupt to prison, from which he could win release only by negotiating a deal with his creditors. Defoe had no fewer than 140 creditors. However, he managed to negotiate his freedom by February 1693, though he dodged debt collectors for the next decade. His misadventures later informed Robinson Crusoe, whose fictional protagonist faces financial ruin as "an overseas trader" and lands bankrupt in prison four times, deeply in "remorse at having ruined his loyal and loving wife."

It gradually dawned on enlightened opinion that putting debtors in prison might be economically irrational. Once behind bars, a debtor stripped of his remaining assets had no means of resuming productive economic life, much less satisfying his debts. In this insight was the germ of Chapter 11.

Defoe soon became England's leading crusader for bankruptcy reform. In 1697, he published the book-length Essay upon Projects, in which he proposed a novel solution. Rather than leaving the debtor to the mercy of his creditors, a "Court of Inquiries" could tally the bankrupt's assets, allocate them to creditors at so many pence in the pound, and leave the debtor with enough money to carry on his business. This legal action, undertaken with the full cooperation of the debtor, would result in the full "discharge" of any remaining obligation to creditors.

London was suffering from the aftermath of bubonic plague and the costs of Britain's recent wars with Spain. Debtors prisons were overflowing, not only with sundry speculators and deadbeats but also with solid businessmen whose enterprises had been ruined by general economic dislocations. In 1705, with the support of Queen Anne's ministers, Parliament took up a reform act, introducing for the first time the concept of discharge.

The legislation, however, was aimed at relief for merchants. Ordinary citizens, fraudulent or just unlucky, could rot in jail. Discharge required the consent of four-fifths of the creditors. When the law was passed in 1706, Defoe himself could not qualify, and he fled to Scotland. Nonetheless, an important concept had been invented. A bankrupt merchant could settle his debts at less than the full sum owed, avoid going to prison, and resume economic life with his debts considered legally discharged. From the outset, there was a double standard of relief for capitalists, but not for the hoi polloi.

Almost a century later, the same scenario played out in the fledgling American republic. After the War of Independence came the financial crash of the 1790s. Robert Morris, the leading financier of the Revolutionary War but later a ruined speculator, was in jail, as was James Wilson, an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. When Congress enacted a temporary bankruptcy law in 1800, it was much in the spirit of the British Act of 1706, providing relief and discharge only for commercial debtors owing at least $1,000, a threshold that excluded ordinary artisans and farmers. When the immediate economic crisis passed, the law was repealed.

Not until 1898 did Congress enact a general and permanent federal bankruptcy statute. It would be amended several times, with oscillating solicitude for debtors and creditors. In the depressed 1930s, Congress added the forerunner of the current Chapter 11 as well as relief for farmers. By the 1980s, the use of Chapter 11 was becoming more frequent, especially in formerly regulated industries that desired to shed wage and pension costs and in companies ruined by hostile takeovers or other leveraged buyouts.

There is indeed a moral-hazard problem, it turns out, but it lies in the increasingly promiscuous use of corporate bankruptcy. The vaunted economic efficiency of Chapter 11 depends on a tacit balancing act between the expedient temptation to blow off your debts and the lingering shame attached to "going bankrupt." If Chapter 11 becomes too common, it ceases to be efficient because it frightens off investors. The supposed shifting of norms, in which people no longer feared the stigma of bankruptcy, was the argument made by bankers in the legislative battle to make bankruptcy less available to ordinary citizens. It was an epic case of corporate America admonishing the citizenry to do as I say, not as I do.

The airline industry is only the extreme case. In the past two decades, the roster of companies that declared bankruptcy includes Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, Adelphia, General Motors, Chrysler, Delphi, Kmart, and LTV Steel, not to mention several major financial houses.

Private-equity companies routinely use Chapter 11 after they bleed dry the operating companies they acquire, load them up with debt, extract capital, and then declare that debts unfortunately exceed assets. Once out of bankruptcy, the company can be sold for more profit. Bain Capital, Mitt Romney's firm, pocketed hundreds of millions of dollars as special dividends from such companies as KB Toys, Dade Behring, Ampad, GS Technologies, and Stage Stores, all of which subsequently filed for bankruptcy. In industries such as steel, airlines, and autos, where good union contracts were once common, one of the biggest appeals of a Chapter 11 reorganization is that contractual pension and retiree health obligations can be swept aside.

In Chapter 11, even the executives who drove a company into the ground get a second chance. Post-bankruptcy, American Airlines' president, Tom Horton, was promoted to CEO. And why not? Declaring bankruptcy will save American a small fortune. American, while in bankruptcy, has nonetheless found the money to pay a firm $525,000 a month to advise it on labor cuts. The firm is Bain Capital.

In the late 1990s, the financial industry concluded that what was available to corporations was too good for the common people. The ease of bankruptcy, supposedly, was inviting consumers to run up credit-card debt and other forms of profligate consumption. The Chamber of Commerce, Business Roundtable, conservative think tanks, and, above all, bankers lined up behind bankruptcy "reform." Congress passed a harsh measure in 2000, but it was pocket-vetoed by President Bill Clinton.

Harvard law professor Elizabeth Warren came to national prominence with her research demonstrating that the charge of frivolous consumer bankruptcies was a red herring. As she demonstrated, most consumer bankruptcies were in fact driven by medical bills that overwhelmed family resources or by other unforeseen financial calamities such as the death or disability of a breadwinner or the breakup of a marriage. She testified in 2005 that during the eight years that the financial industry was promoting a harsher consumer bankruptcy law, the number of bankruptcy filings actually increased a modest 17 percent, while credit-card profits went up 163 percent to $30.2 billion.

With the accession of President George W. Bush and Republican control of Congress in 2001, the banking industry increased its efforts to tilt the bankruptcy code against consumers, spending about $100 million in lobbying over eight years. In 2005, Bush signed the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act. Its key provisions made it more difficult for consumers to file under Chapter 7, under which most debts are paid out of only existing assets and then forgiven, and compelled more people to file under Chapter 13, which requires a partial repayment plan over three to five years. The act introduced for the first time a means test, in which only debtors with income below the state's median are exempt from the more onerous provisions of the law. If a citizen has above-median income, there is a "presumption" of abuse, and future income is partly attached in order to satisfy past creditor claims, no matter what the circumstances. Many states have a "homestead exemption" protecting an owner-occupied home, up to a dollar limit, from creditor claims. This, too, is overridden by the 2005 federal act.

In promoting the law, financial executives testified that if losses could be reduced, savings would be passed along to the public in the form of lower interest rates. But after the law passed, the credit-card industry increased its efforts to market high-interest-rate credit cards to consumers, including those with poor credit ratings. Adding insult to injury, the industry invented new fees. Thanks to the "reform," when overburdened consumers did go broke, credit-card companies now had far more latitude to squeeze them for repayment.

Testifying against the bill, Elizabeth Warren warned:

Women trying to collect alimony or child support will more often be forced to compete with credit-card companies that can have more of their debts declared non--dischargeable. All these provisions apply whether a person earns $20,000 a year or $200,000 a year.

But the means test as written has another, more basic problem: It treats all families alike. It assumes that everyone is in bankruptcy for the same reason--too much unnecessary spending. A family driven to bankruptcy by the increased costs of caring for an elderly parent with Alzheimer's disease is treated the same as someone who maxed out his credit cards at a casino. A person who had a heart attack is treated the same as someone who had a spending spree at the shopping mall. A mother who works two jobs and who cannot manage the prescription drugs needed for a child with diabetes is treated the same as someone who charged a bunch of credit cards with only a vague intent to repay. A person cheated by a subprime mortgage lender and lied to by a credit-counseling agency is treated the same as a person who gamed the system in every possible way.

At bottom, this trend was a rendezvous between flat or falling wages and banks making it ever easier for consumers to go more deeply into debt. Inflated assets--which turned out to be a bubble--were advertised as a substitute for income. Are your earnings down? Just borrow against your home. Between 1989 and 2004, credit-card debt tripled, to $800 billion, while earnings stagnated. Homeowners borrowed trillions more against the supposed value of their home. The moral vocabulary of debt is filled with denunciations about improvident borrowers, but who ever heard of an improvident lender? Yet it was the recklessness of banks that caused the financial collapse.

The financial crash that began rumbling in 2007 had numerous consequences, but in many ways the most durable and destructive one is the continuing undertow of the housing collapse. The collapse began with a housing bubble pumped up by subprime mortgages. It is being prolonged by the loss of several trillion dollars in household assets representing the collapse of housing prices. With about one homeowner in five holding a mortgage that exceeds the value of the house, and more than a million homeowners defaulting every year, the result is forced sales into a depressed housing market. This puts further downward pressure on prices, prolonging and deepening a classic deflationary spiral.

The housing deflation is such a widely recognized cause of the persistent economic slump that even the Federal Reserve has publicly criticized the Obama administration for its feeble response to the housing/mortgage crisis. Bill Dudley, president of the New York Federal Reserve, recently told a bankers' convention, "The ongoing weakness in housing has made it more difficult to achieve a vigorous economic recovery. With additional housing-policy interventions, we could achieve a better set of economic outcomes."

The administration's housing policy has been built on two programs of shallow relief, both intended to avoid direct reduction in principal owed and both widely dismissed as failures. The first, the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP), gives mortgage servicers bonus payments for voluntarily reducing monthly payments. It has helped fewer than one underwater homeowner in ten, and as many as half of those who get HAMP relief go right back into default. The program is a well-documented bureaucratic nightmare for the homeowner. The second, more recent program, known as HARP, for Home Affordable Refinance Program, allows moderately underwater homeowners to refinance mortgages held by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as long as the debt is not more than 125 percent of the value of the home. But HARP does not reduce the principal owed, and its terms exclude those most in need of relief. The much-touted legal deal announced February 1, supposedly worth $26 billion, would actually give homeowners about $3 billion in mortgage write-downs (the rest is accounting changes and counseling outlays), compared to a $700 billion gap between the market value of homes and the mortgages against them.

The more straightforward solution, analogous to a corporate Chapter 11, would be to give a bankruptcy judge the power to adjust the outstanding mortgage debt. When congressional progressives proposed this as part of the legislation creating HAMP, Wall Street fiercely resisted. Several Democrats as well as nearly all Republicans ended up voting against it. Direct relief, from the perspective of the financial industry and its allies in the Treasury, is odious because it would require banks to acknowledge the actual, as opposed to nominal, condition of their balance sheets.

So while corporations continue to get a fresh start under Chapter 11, the aftermath of the financial crisis continues to sandbag millions of homeowners and the economy as a whole. This double standard is not just a question of fairness. The selective relief for corporations and banks, but not for the 99 percent, is killing the recovery. None of this will change until the citizenry builds a politics that demands a single standard.

This piece draws on the themes of a book that Robert Kuttner is completing for Knopf, titled Debtors Prison.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

"But, Yossarian, suppose everyone felt that way."

"Then," said Yossarian, "I'd certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way, wouldn't I?" --Joseph Heller, Catch-22

Last November 29, American Airlines declared bankruptcy under Chapter 11, the provision of the bankruptcy code that allows a corporation to stiff its creditors, break contracts, and keep operating under the supervision of a judge. This maneuver, politely termed a "reorganization," ends with the corporation exiting bankruptcy cleansed of old debts. In opting for Chapter 11, American joined every other major airline, including Delta, Northwest, United, and US Airways, which has been in and out of Chapter 11 twice since 2002. No fewer than 189 airlines have declared bankruptcy since 1990. As the sole large carrier that had not gone bankrupt, American missed out on savings available to its rivals and thus was increasingly uncompetitive.

Bankruptcy is intended to give a fresh start to persons and enterprises overwhelmed by creditors. In the case of American (like other airlines before it), the main "creditors" are its employees. The costs of American's bankruptcy will be borne mainly by its workers and secondarily by taxpayers. The contracts being broken are union contracts and legal promises to honor pension obligations. American is laying off 13,000 workers, slashing wages, and reducing its annual pension contribution from $97 million to $6.5 million. The airline hopes to stick the federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation with liability for much of the $6.5 billion that it owes its workers and retirees.

This national indulgence for corporate bankruptcy has a certain logic. The Wall Street Journal editorial page recently termed bankruptcy "one of the better ways in which American capitalism encourages risk-taking," and that is the prevailing view. Thanks to Chapter 11, a potentially viable insolvent enterprise is given a fresh start as a going concern, rather than being cannibalized for the benefit of its creditors.

However, what's good for corporate capitalism is evidently too good for the rest of us. Suppose everyone felt that way?

Wall Street has convinced lawmakers that relief for the masses, even in a deflationary economic emergency, would not only inflict unacceptable costs to bank balance sheets; it would also promote "moral hazard"--the economist's term for rewarding and thereby inviting improvident behavior. Thanks to a revision in the bankruptcy law passed in 2005 and signed by President George W. Bush after nearly a decade of furious lobbying by the credit-card industry and the banks, consumers generally face far more onerous bankruptcy terms than do corporations.

The housing collapse, depressing trillions of dollars of consumer assets, is the single biggest drag on the recovery. But underwater mortgage holders, unlike submerged corporations, have never been eligible for bankruptcy relief. Homeowners are explicitly prohibited from using the bankruptcy code to reduce the amount of the mortgage to the present value of the house or to a monthly payment that could enable them to keep their home.

The selective privileges of bankruptcy display yet another facet of the convenient concept of corporate personhood. Some persons are evidently more equal than others. The gross disparity in the way that bankruptcy law treats corporate persons and actual people is only one of multiple double standards that increasingly define our age.

Petty felons and 200,000 small-time drug users do prison time, while corporate criminals whose frauds cost the rest of the economy trillions of dollars are permitted to settle civil suits for small fines, with shareholders bearing the expenses. Ordinary families pay tax at a higher rate than billionaires. When fracking contaminates a property and makes a home uninhabitable, the homeowner rather than the natural-gas company suffers the loss. The mother of all double standards is taxpayer aid and Federal Reserve advances--running into the trillions of dollars--that went to the banks that caused the collapse, while the bankers avoided prosecution, and the rest of the society got to eat austerity.

Linking all of these disparities between citizens and corporations is the political power of a new American plutocracy. Until our politics connects these dots and citizens start resisting, the financial elite will rule. Despite the Occupy movement, most regular people have yet to experience the sudden enlightenment of Captain Yossarian, who decided, unpatriotically, that he didn't want to die. In the face of economic pillaging, we are behaving like damned fools.

Bankruptcy privileges for the elite have been with us for centuries. On October 29, 1692, Daniel Defoe, merchant, pamphleteer, and the future best-selling author of Robinson Crusoe, was committed to London's King's Bench Prison because he could not pay debts that totaled some 17,000 pounds. Before Defoe was declared bankrupt, his far-flung ventures had included underwriting marine insurance, importing wine from Portugal, buying a diving bell to search for buried treasure, and investing in 70 civet cats whose musk secretions were prized for the manufacture of perfume.

In that era, there was no Chapter 11. Bankrupts like Defoe ended up in debtors prison, an institution that would persist well into the 19th century. Typically, creditors could obtain a writ of seizure of the debtor's assets (historians record that Defoe's civet cats were taken by the sheriff's men); if the assets were insufficient to settle the debt, another writ would send the bankrupt to prison, from which he could win release only by negotiating a deal with his creditors. Defoe had no fewer than 140 creditors. However, he managed to negotiate his freedom by February 1693, though he dodged debt collectors for the next decade. His misadventures later informed Robinson Crusoe, whose fictional protagonist faces financial ruin as "an overseas trader" and lands bankrupt in prison four times, deeply in "remorse at having ruined his loyal and loving wife."

It gradually dawned on enlightened opinion that putting debtors in prison might be economically irrational. Once behind bars, a debtor stripped of his remaining assets had no means of resuming productive economic life, much less satisfying his debts. In this insight was the germ of Chapter 11.

Defoe soon became England's leading crusader for bankruptcy reform. In 1697, he published the book-length Essay upon Projects, in which he proposed a novel solution. Rather than leaving the debtor to the mercy of his creditors, a "Court of Inquiries" could tally the bankrupt's assets, allocate them to creditors at so many pence in the pound, and leave the debtor with enough money to carry on his business. This legal action, undertaken with the full cooperation of the debtor, would result in the full "discharge" of any remaining obligation to creditors.

London was suffering from the aftermath of bubonic plague and the costs of Britain's recent wars with Spain. Debtors prisons were overflowing, not only with sundry speculators and deadbeats but also with solid businessmen whose enterprises had been ruined by general economic dislocations. In 1705, with the support of Queen Anne's ministers, Parliament took up a reform act, introducing for the first time the concept of discharge.

The legislation, however, was aimed at relief for merchants. Ordinary citizens, fraudulent or just unlucky, could rot in jail. Discharge required the consent of four-fifths of the creditors. When the law was passed in 1706, Defoe himself could not qualify, and he fled to Scotland. Nonetheless, an important concept had been invented. A bankrupt merchant could settle his debts at less than the full sum owed, avoid going to prison, and resume economic life with his debts considered legally discharged. From the outset, there was a double standard of relief for capitalists, but not for the hoi polloi.

Almost a century later, the same scenario played out in the fledgling American republic. After the War of Independence came the financial crash of the 1790s. Robert Morris, the leading financier of the Revolutionary War but later a ruined speculator, was in jail, as was James Wilson, an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. When Congress enacted a temporary bankruptcy law in 1800, it was much in the spirit of the British Act of 1706, providing relief and discharge only for commercial debtors owing at least $1,000, a threshold that excluded ordinary artisans and farmers. When the immediate economic crisis passed, the law was repealed.

Not until 1898 did Congress enact a general and permanent federal bankruptcy statute. It would be amended several times, with oscillating solicitude for debtors and creditors. In the depressed 1930s, Congress added the forerunner of the current Chapter 11 as well as relief for farmers. By the 1980s, the use of Chapter 11 was becoming more frequent, especially in formerly regulated industries that desired to shed wage and pension costs and in companies ruined by hostile takeovers or other leveraged buyouts.

There is indeed a moral-hazard problem, it turns out, but it lies in the increasingly promiscuous use of corporate bankruptcy. The vaunted economic efficiency of Chapter 11 depends on a tacit balancing act between the expedient temptation to blow off your debts and the lingering shame attached to "going bankrupt." If Chapter 11 becomes too common, it ceases to be efficient because it frightens off investors. The supposed shifting of norms, in which people no longer feared the stigma of bankruptcy, was the argument made by bankers in the legislative battle to make bankruptcy less available to ordinary citizens. It was an epic case of corporate America admonishing the citizenry to do as I say, not as I do.

The airline industry is only the extreme case. In the past two decades, the roster of companies that declared bankruptcy includes Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, Adelphia, General Motors, Chrysler, Delphi, Kmart, and LTV Steel, not to mention several major financial houses.

Private-equity companies routinely use Chapter 11 after they bleed dry the operating companies they acquire, load them up with debt, extract capital, and then declare that debts unfortunately exceed assets. Once out of bankruptcy, the company can be sold for more profit. Bain Capital, Mitt Romney's firm, pocketed hundreds of millions of dollars as special dividends from such companies as KB Toys, Dade Behring, Ampad, GS Technologies, and Stage Stores, all of which subsequently filed for bankruptcy. In industries such as steel, airlines, and autos, where good union contracts were once common, one of the biggest appeals of a Chapter 11 reorganization is that contractual pension and retiree health obligations can be swept aside.

In Chapter 11, even the executives who drove a company into the ground get a second chance. Post-bankruptcy, American Airlines' president, Tom Horton, was promoted to CEO. And why not? Declaring bankruptcy will save American a small fortune. American, while in bankruptcy, has nonetheless found the money to pay a firm $525,000 a month to advise it on labor cuts. The firm is Bain Capital.

In the late 1990s, the financial industry concluded that what was available to corporations was too good for the common people. The ease of bankruptcy, supposedly, was inviting consumers to run up credit-card debt and other forms of profligate consumption. The Chamber of Commerce, Business Roundtable, conservative think tanks, and, above all, bankers lined up behind bankruptcy "reform." Congress passed a harsh measure in 2000, but it was pocket-vetoed by President Bill Clinton.

Harvard law professor Elizabeth Warren came to national prominence with her research demonstrating that the charge of frivolous consumer bankruptcies was a red herring. As she demonstrated, most consumer bankruptcies were in fact driven by medical bills that overwhelmed family resources or by other unforeseen financial calamities such as the death or disability of a breadwinner or the breakup of a marriage. She testified in 2005 that during the eight years that the financial industry was promoting a harsher consumer bankruptcy law, the number of bankruptcy filings actually increased a modest 17 percent, while credit-card profits went up 163 percent to $30.2 billion.

With the accession of President George W. Bush and Republican control of Congress in 2001, the banking industry increased its efforts to tilt the bankruptcy code against consumers, spending about $100 million in lobbying over eight years. In 2005, Bush signed the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act. Its key provisions made it more difficult for consumers to file under Chapter 7, under which most debts are paid out of only existing assets and then forgiven, and compelled more people to file under Chapter 13, which requires a partial repayment plan over three to five years. The act introduced for the first time a means test, in which only debtors with income below the state's median are exempt from the more onerous provisions of the law. If a citizen has above-median income, there is a "presumption" of abuse, and future income is partly attached in order to satisfy past creditor claims, no matter what the circumstances. Many states have a "homestead exemption" protecting an owner-occupied home, up to a dollar limit, from creditor claims. This, too, is overridden by the 2005 federal act.

In promoting the law, financial executives testified that if losses could be reduced, savings would be passed along to the public in the form of lower interest rates. But after the law passed, the credit-card industry increased its efforts to market high-interest-rate credit cards to consumers, including those with poor credit ratings. Adding insult to injury, the industry invented new fees. Thanks to the "reform," when overburdened consumers did go broke, credit-card companies now had far more latitude to squeeze them for repayment.

Testifying against the bill, Elizabeth Warren warned:

Women trying to collect alimony or child support will more often be forced to compete with credit-card companies that can have more of their debts declared non--dischargeable. All these provisions apply whether a person earns $20,000 a year or $200,000 a year.

But the means test as written has another, more basic problem: It treats all families alike. It assumes that everyone is in bankruptcy for the same reason--too much unnecessary spending. A family driven to bankruptcy by the increased costs of caring for an elderly parent with Alzheimer's disease is treated the same as someone who maxed out his credit cards at a casino. A person who had a heart attack is treated the same as someone who had a spending spree at the shopping mall. A mother who works two jobs and who cannot manage the prescription drugs needed for a child with diabetes is treated the same as someone who charged a bunch of credit cards with only a vague intent to repay. A person cheated by a subprime mortgage lender and lied to by a credit-counseling agency is treated the same as a person who gamed the system in every possible way.

At bottom, this trend was a rendezvous between flat or falling wages and banks making it ever easier for consumers to go more deeply into debt. Inflated assets--which turned out to be a bubble--were advertised as a substitute for income. Are your earnings down? Just borrow against your home. Between 1989 and 2004, credit-card debt tripled, to $800 billion, while earnings stagnated. Homeowners borrowed trillions more against the supposed value of their home. The moral vocabulary of debt is filled with denunciations about improvident borrowers, but who ever heard of an improvident lender? Yet it was the recklessness of banks that caused the financial collapse.

The financial crash that began rumbling in 2007 had numerous consequences, but in many ways the most durable and destructive one is the continuing undertow of the housing collapse. The collapse began with a housing bubble pumped up by subprime mortgages. It is being prolonged by the loss of several trillion dollars in household assets representing the collapse of housing prices. With about one homeowner in five holding a mortgage that exceeds the value of the house, and more than a million homeowners defaulting every year, the result is forced sales into a depressed housing market. This puts further downward pressure on prices, prolonging and deepening a classic deflationary spiral.

The housing deflation is such a widely recognized cause of the persistent economic slump that even the Federal Reserve has publicly criticized the Obama administration for its feeble response to the housing/mortgage crisis. Bill Dudley, president of the New York Federal Reserve, recently told a bankers' convention, "The ongoing weakness in housing has made it more difficult to achieve a vigorous economic recovery. With additional housing-policy interventions, we could achieve a better set of economic outcomes."

The administration's housing policy has been built on two programs of shallow relief, both intended to avoid direct reduction in principal owed and both widely dismissed as failures. The first, the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP), gives mortgage servicers bonus payments for voluntarily reducing monthly payments. It has helped fewer than one underwater homeowner in ten, and as many as half of those who get HAMP relief go right back into default. The program is a well-documented bureaucratic nightmare for the homeowner. The second, more recent program, known as HARP, for Home Affordable Refinance Program, allows moderately underwater homeowners to refinance mortgages held by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as long as the debt is not more than 125 percent of the value of the home. But HARP does not reduce the principal owed, and its terms exclude those most in need of relief. The much-touted legal deal announced February 1, supposedly worth $26 billion, would actually give homeowners about $3 billion in mortgage write-downs (the rest is accounting changes and counseling outlays), compared to a $700 billion gap between the market value of homes and the mortgages against them.

The more straightforward solution, analogous to a corporate Chapter 11, would be to give a bankruptcy judge the power to adjust the outstanding mortgage debt. When congressional progressives proposed this as part of the legislation creating HAMP, Wall Street fiercely resisted. Several Democrats as well as nearly all Republicans ended up voting against it. Direct relief, from the perspective of the financial industry and its allies in the Treasury, is odious because it would require banks to acknowledge the actual, as opposed to nominal, condition of their balance sheets.

So while corporations continue to get a fresh start under Chapter 11, the aftermath of the financial crisis continues to sandbag millions of homeowners and the economy as a whole. This double standard is not just a question of fairness. The selective relief for corporations and banks, but not for the 99 percent, is killing the recovery. None of this will change until the citizenry builds a politics that demands a single standard.

This piece draws on the themes of a book that Robert Kuttner is completing for Knopf, titled Debtors Prison.

"But, Yossarian, suppose everyone felt that way."

"Then," said Yossarian, "I'd certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way, wouldn't I?" --Joseph Heller, Catch-22

Last November 29, American Airlines declared bankruptcy under Chapter 11, the provision of the bankruptcy code that allows a corporation to stiff its creditors, break contracts, and keep operating under the supervision of a judge. This maneuver, politely termed a "reorganization," ends with the corporation exiting bankruptcy cleansed of old debts. In opting for Chapter 11, American joined every other major airline, including Delta, Northwest, United, and US Airways, which has been in and out of Chapter 11 twice since 2002. No fewer than 189 airlines have declared bankruptcy since 1990. As the sole large carrier that had not gone bankrupt, American missed out on savings available to its rivals and thus was increasingly uncompetitive.

Bankruptcy is intended to give a fresh start to persons and enterprises overwhelmed by creditors. In the case of American (like other airlines before it), the main "creditors" are its employees. The costs of American's bankruptcy will be borne mainly by its workers and secondarily by taxpayers. The contracts being broken are union contracts and legal promises to honor pension obligations. American is laying off 13,000 workers, slashing wages, and reducing its annual pension contribution from $97 million to $6.5 million. The airline hopes to stick the federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation with liability for much of the $6.5 billion that it owes its workers and retirees.

This national indulgence for corporate bankruptcy has a certain logic. The Wall Street Journal editorial page recently termed bankruptcy "one of the better ways in which American capitalism encourages risk-taking," and that is the prevailing view. Thanks to Chapter 11, a potentially viable insolvent enterprise is given a fresh start as a going concern, rather than being cannibalized for the benefit of its creditors.

However, what's good for corporate capitalism is evidently too good for the rest of us. Suppose everyone felt that way?

Wall Street has convinced lawmakers that relief for the masses, even in a deflationary economic emergency, would not only inflict unacceptable costs to bank balance sheets; it would also promote "moral hazard"--the economist's term for rewarding and thereby inviting improvident behavior. Thanks to a revision in the bankruptcy law passed in 2005 and signed by President George W. Bush after nearly a decade of furious lobbying by the credit-card industry and the banks, consumers generally face far more onerous bankruptcy terms than do corporations.

The housing collapse, depressing trillions of dollars of consumer assets, is the single biggest drag on the recovery. But underwater mortgage holders, unlike submerged corporations, have never been eligible for bankruptcy relief. Homeowners are explicitly prohibited from using the bankruptcy code to reduce the amount of the mortgage to the present value of the house or to a monthly payment that could enable them to keep their home.

The selective privileges of bankruptcy display yet another facet of the convenient concept of corporate personhood. Some persons are evidently more equal than others. The gross disparity in the way that bankruptcy law treats corporate persons and actual people is only one of multiple double standards that increasingly define our age.

Petty felons and 200,000 small-time drug users do prison time, while corporate criminals whose frauds cost the rest of the economy trillions of dollars are permitted to settle civil suits for small fines, with shareholders bearing the expenses. Ordinary families pay tax at a higher rate than billionaires. When fracking contaminates a property and makes a home uninhabitable, the homeowner rather than the natural-gas company suffers the loss. The mother of all double standards is taxpayer aid and Federal Reserve advances--running into the trillions of dollars--that went to the banks that caused the collapse, while the bankers avoided prosecution, and the rest of the society got to eat austerity.

Linking all of these disparities between citizens and corporations is the political power of a new American plutocracy. Until our politics connects these dots and citizens start resisting, the financial elite will rule. Despite the Occupy movement, most regular people have yet to experience the sudden enlightenment of Captain Yossarian, who decided, unpatriotically, that he didn't want to die. In the face of economic pillaging, we are behaving like damned fools.

Bankruptcy privileges for the elite have been with us for centuries. On October 29, 1692, Daniel Defoe, merchant, pamphleteer, and the future best-selling author of Robinson Crusoe, was committed to London's King's Bench Prison because he could not pay debts that totaled some 17,000 pounds. Before Defoe was declared bankrupt, his far-flung ventures had included underwriting marine insurance, importing wine from Portugal, buying a diving bell to search for buried treasure, and investing in 70 civet cats whose musk secretions were prized for the manufacture of perfume.

In that era, there was no Chapter 11. Bankrupts like Defoe ended up in debtors prison, an institution that would persist well into the 19th century. Typically, creditors could obtain a writ of seizure of the debtor's assets (historians record that Defoe's civet cats were taken by the sheriff's men); if the assets were insufficient to settle the debt, another writ would send the bankrupt to prison, from which he could win release only by negotiating a deal with his creditors. Defoe had no fewer than 140 creditors. However, he managed to negotiate his freedom by February 1693, though he dodged debt collectors for the next decade. His misadventures later informed Robinson Crusoe, whose fictional protagonist faces financial ruin as "an overseas trader" and lands bankrupt in prison four times, deeply in "remorse at having ruined his loyal and loving wife."

It gradually dawned on enlightened opinion that putting debtors in prison might be economically irrational. Once behind bars, a debtor stripped of his remaining assets had no means of resuming productive economic life, much less satisfying his debts. In this insight was the germ of Chapter 11.

Defoe soon became England's leading crusader for bankruptcy reform. In 1697, he published the book-length Essay upon Projects, in which he proposed a novel solution. Rather than leaving the debtor to the mercy of his creditors, a "Court of Inquiries" could tally the bankrupt's assets, allocate them to creditors at so many pence in the pound, and leave the debtor with enough money to carry on his business. This legal action, undertaken with the full cooperation of the debtor, would result in the full "discharge" of any remaining obligation to creditors.

London was suffering from the aftermath of bubonic plague and the costs of Britain's recent wars with Spain. Debtors prisons were overflowing, not only with sundry speculators and deadbeats but also with solid businessmen whose enterprises had been ruined by general economic dislocations. In 1705, with the support of Queen Anne's ministers, Parliament took up a reform act, introducing for the first time the concept of discharge.

The legislation, however, was aimed at relief for merchants. Ordinary citizens, fraudulent or just unlucky, could rot in jail. Discharge required the consent of four-fifths of the creditors. When the law was passed in 1706, Defoe himself could not qualify, and he fled to Scotland. Nonetheless, an important concept had been invented. A bankrupt merchant could settle his debts at less than the full sum owed, avoid going to prison, and resume economic life with his debts considered legally discharged. From the outset, there was a double standard of relief for capitalists, but not for the hoi polloi.

Almost a century later, the same scenario played out in the fledgling American republic. After the War of Independence came the financial crash of the 1790s. Robert Morris, the leading financier of the Revolutionary War but later a ruined speculator, was in jail, as was James Wilson, an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. When Congress enacted a temporary bankruptcy law in 1800, it was much in the spirit of the British Act of 1706, providing relief and discharge only for commercial debtors owing at least $1,000, a threshold that excluded ordinary artisans and farmers. When the immediate economic crisis passed, the law was repealed.

Not until 1898 did Congress enact a general and permanent federal bankruptcy statute. It would be amended several times, with oscillating solicitude for debtors and creditors. In the depressed 1930s, Congress added the forerunner of the current Chapter 11 as well as relief for farmers. By the 1980s, the use of Chapter 11 was becoming more frequent, especially in formerly regulated industries that desired to shed wage and pension costs and in companies ruined by hostile takeovers or other leveraged buyouts.

There is indeed a moral-hazard problem, it turns out, but it lies in the increasingly promiscuous use of corporate bankruptcy. The vaunted economic efficiency of Chapter 11 depends on a tacit balancing act between the expedient temptation to blow off your debts and the lingering shame attached to "going bankrupt." If Chapter 11 becomes too common, it ceases to be efficient because it frightens off investors. The supposed shifting of norms, in which people no longer feared the stigma of bankruptcy, was the argument made by bankers in the legislative battle to make bankruptcy less available to ordinary citizens. It was an epic case of corporate America admonishing the citizenry to do as I say, not as I do.

The airline industry is only the extreme case. In the past two decades, the roster of companies that declared bankruptcy includes Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, Adelphia, General Motors, Chrysler, Delphi, Kmart, and LTV Steel, not to mention several major financial houses.

Private-equity companies routinely use Chapter 11 after they bleed dry the operating companies they acquire, load them up with debt, extract capital, and then declare that debts unfortunately exceed assets. Once out of bankruptcy, the company can be sold for more profit. Bain Capital, Mitt Romney's firm, pocketed hundreds of millions of dollars as special dividends from such companies as KB Toys, Dade Behring, Ampad, GS Technologies, and Stage Stores, all of which subsequently filed for bankruptcy. In industries such as steel, airlines, and autos, where good union contracts were once common, one of the biggest appeals of a Chapter 11 reorganization is that contractual pension and retiree health obligations can be swept aside.

In Chapter 11, even the executives who drove a company into the ground get a second chance. Post-bankruptcy, American Airlines' president, Tom Horton, was promoted to CEO. And why not? Declaring bankruptcy will save American a small fortune. American, while in bankruptcy, has nonetheless found the money to pay a firm $525,000 a month to advise it on labor cuts. The firm is Bain Capital.

In the late 1990s, the financial industry concluded that what was available to corporations was too good for the common people. The ease of bankruptcy, supposedly, was inviting consumers to run up credit-card debt and other forms of profligate consumption. The Chamber of Commerce, Business Roundtable, conservative think tanks, and, above all, bankers lined up behind bankruptcy "reform." Congress passed a harsh measure in 2000, but it was pocket-vetoed by President Bill Clinton.

Harvard law professor Elizabeth Warren came to national prominence with her research demonstrating that the charge of frivolous consumer bankruptcies was a red herring. As she demonstrated, most consumer bankruptcies were in fact driven by medical bills that overwhelmed family resources or by other unforeseen financial calamities such as the death or disability of a breadwinner or the breakup of a marriage. She testified in 2005 that during the eight years that the financial industry was promoting a harsher consumer bankruptcy law, the number of bankruptcy filings actually increased a modest 17 percent, while credit-card profits went up 163 percent to $30.2 billion.

With the accession of President George W. Bush and Republican control of Congress in 2001, the banking industry increased its efforts to tilt the bankruptcy code against consumers, spending about $100 million in lobbying over eight years. In 2005, Bush signed the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act. Its key provisions made it more difficult for consumers to file under Chapter 7, under which most debts are paid out of only existing assets and then forgiven, and compelled more people to file under Chapter 13, which requires a partial repayment plan over three to five years. The act introduced for the first time a means test, in which only debtors with income below the state's median are exempt from the more onerous provisions of the law. If a citizen has above-median income, there is a "presumption" of abuse, and future income is partly attached in order to satisfy past creditor claims, no matter what the circumstances. Many states have a "homestead exemption" protecting an owner-occupied home, up to a dollar limit, from creditor claims. This, too, is overridden by the 2005 federal act.

In promoting the law, financial executives testified that if losses could be reduced, savings would be passed along to the public in the form of lower interest rates. But after the law passed, the credit-card industry increased its efforts to market high-interest-rate credit cards to consumers, including those with poor credit ratings. Adding insult to injury, the industry invented new fees. Thanks to the "reform," when overburdened consumers did go broke, credit-card companies now had far more latitude to squeeze them for repayment.

Testifying against the bill, Elizabeth Warren warned:

Women trying to collect alimony or child support will more often be forced to compete with credit-card companies that can have more of their debts declared non--dischargeable. All these provisions apply whether a person earns $20,000 a year or $200,000 a year.

But the means test as written has another, more basic problem: It treats all families alike. It assumes that everyone is in bankruptcy for the same reason--too much unnecessary spending. A family driven to bankruptcy by the increased costs of caring for an elderly parent with Alzheimer's disease is treated the same as someone who maxed out his credit cards at a casino. A person who had a heart attack is treated the same as someone who had a spending spree at the shopping mall. A mother who works two jobs and who cannot manage the prescription drugs needed for a child with diabetes is treated the same as someone who charged a bunch of credit cards with only a vague intent to repay. A person cheated by a subprime mortgage lender and lied to by a credit-counseling agency is treated the same as a person who gamed the system in every possible way.

At bottom, this trend was a rendezvous between flat or falling wages and banks making it ever easier for consumers to go more deeply into debt. Inflated assets--which turned out to be a bubble--were advertised as a substitute for income. Are your earnings down? Just borrow against your home. Between 1989 and 2004, credit-card debt tripled, to $800 billion, while earnings stagnated. Homeowners borrowed trillions more against the supposed value of their home. The moral vocabulary of debt is filled with denunciations about improvident borrowers, but who ever heard of an improvident lender? Yet it was the recklessness of banks that caused the financial collapse.

The financial crash that began rumbling in 2007 had numerous consequences, but in many ways the most durable and destructive one is the continuing undertow of the housing collapse. The collapse began with a housing bubble pumped up by subprime mortgages. It is being prolonged by the loss of several trillion dollars in household assets representing the collapse of housing prices. With about one homeowner in five holding a mortgage that exceeds the value of the house, and more than a million homeowners defaulting every year, the result is forced sales into a depressed housing market. This puts further downward pressure on prices, prolonging and deepening a classic deflationary spiral.

The housing deflation is such a widely recognized cause of the persistent economic slump that even the Federal Reserve has publicly criticized the Obama administration for its feeble response to the housing/mortgage crisis. Bill Dudley, president of the New York Federal Reserve, recently told a bankers' convention, "The ongoing weakness in housing has made it more difficult to achieve a vigorous economic recovery. With additional housing-policy interventions, we could achieve a better set of economic outcomes."

The administration's housing policy has been built on two programs of shallow relief, both intended to avoid direct reduction in principal owed and both widely dismissed as failures. The first, the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP), gives mortgage servicers bonus payments for voluntarily reducing monthly payments. It has helped fewer than one underwater homeowner in ten, and as many as half of those who get HAMP relief go right back into default. The program is a well-documented bureaucratic nightmare for the homeowner. The second, more recent program, known as HARP, for Home Affordable Refinance Program, allows moderately underwater homeowners to refinance mortgages held by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as long as the debt is not more than 125 percent of the value of the home. But HARP does not reduce the principal owed, and its terms exclude those most in need of relief. The much-touted legal deal announced February 1, supposedly worth $26 billion, would actually give homeowners about $3 billion in mortgage write-downs (the rest is accounting changes and counseling outlays), compared to a $700 billion gap between the market value of homes and the mortgages against them.

The more straightforward solution, analogous to a corporate Chapter 11, would be to give a bankruptcy judge the power to adjust the outstanding mortgage debt. When congressional progressives proposed this as part of the legislation creating HAMP, Wall Street fiercely resisted. Several Democrats as well as nearly all Republicans ended up voting against it. Direct relief, from the perspective of the financial industry and its allies in the Treasury, is odious because it would require banks to acknowledge the actual, as opposed to nominal, condition of their balance sheets.

So while corporations continue to get a fresh start under Chapter 11, the aftermath of the financial crisis continues to sandbag millions of homeowners and the economy as a whole. This double standard is not just a question of fairness. The selective relief for corporations and banks, but not for the 99 percent, is killing the recovery. None of this will change until the citizenry builds a politics that demands a single standard.

This piece draws on the themes of a book that Robert Kuttner is completing for Knopf, titled Debtors Prison.