SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

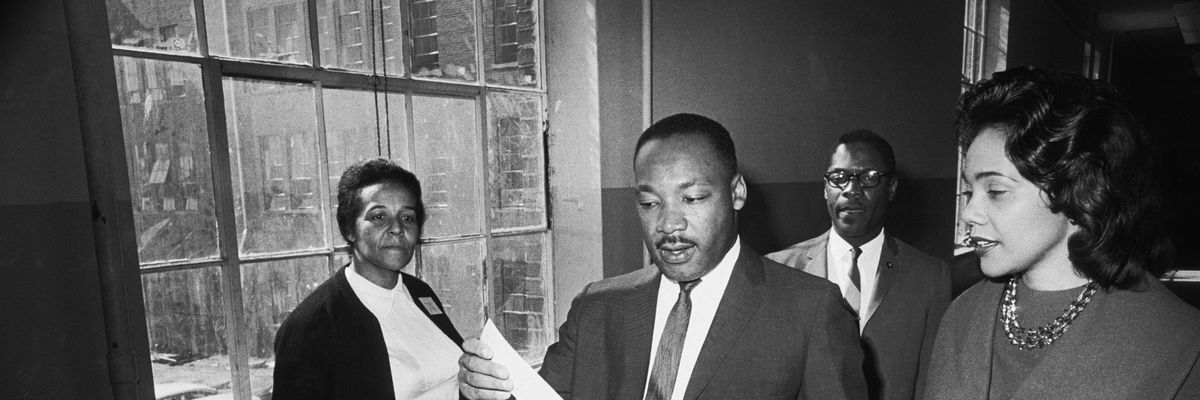

In November of 1964, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr votes as his wife, Coretta Scott King, waits her turn in Atlanta, Georgia. (Photo: Bettman / via Getty Images)

Voting rights and electoral fairness are currently the most contested issues in our extremely polarized political system. And the best way to advance these essential values is to make clear the inextricable link between the moral and the practical.

The Republican party, and tens of millions of those citizens who support it, are now following the logic of the "Stop the Steal" rhetoric of disgraced, twice-impeached, former President Trump. Maintaining that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen (but, miraculously, the many elections that they won were not stolen), and claiming that the Democrats are determined to commit election fraud in the future, they are committed to changing state elections laws to make it harder to vote and easier for their party leaders to overturn "stolen" elections. And they are also committed to opposing any effort to protect voting rights and non-partisan elections through federal legislation.

"We should remember that King's courageous effort to make real the promise of American democracy always joined the moral claim to equal voting rights with the practical understanding that voting rights were a means and an instrument whereby ordinary citizens could mobilize political power so as to make the world a better place to live decent and meaningful lives."

They must be defeated. Defeating them is necessary in order to "vindicate" the slim "victory" that Democrats claimed in 2020, and to make possible more decisive victories in the future. Failure is not an option if even the most threadbare version of constitutional democracy is to be saved.

The approach of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day has been an especially appropriate moment for the question move to center stage. In their addresses last week, both President Biden and Vice President Harris made explicit the connection between current Republican voter suppression efforts and the history of Jim Crow, and between Democratic support for federal legislation--the John Lewis Act, the Freedom to Vote Act--and the civil rights movement.

Toda's commemoration of King is a wonderful occasion to recall his own emphasis on the centrality of voting rights. Colbert I. King does a great job of this in his recent Washington Post piece, "Martin Luther King Jr.'s words on voting rights resonate all too well today."

The piece, which centers on King's important 1957 speech, "Give Us the Ballot," powerfully emphasizes the moral demand for human dignity underlying King's advocacy. But it misses one important element of King's actual defense of voting rights: the indissoluble link between voting rights and all other rights, and the way that without the right to vote, citizens are disabled from voicing their concerns and from protecting themselves from abuse and injustice.

In his speech, King insists that "The denial of this sacred right is a tragic betrayal of the highest mandates of our democratic tradition." He then immediately segues to the consequences that would follow from the protection of voting rights:

Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights.

Give us the ballot (Yes), and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South (All right) and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

Give us the ballot (Give us the ballot), and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs (Yeah) into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens.

Give us the ballot (Give us the ballot), and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill (All right now) and send to the sacred halls of Congress men who will not sign a "Southern Manifesto" because of their devotion to the manifesto of justice. (Tell 'em about it)

Give us the ballot (Yeah), and we will place judges on the benches of the South who will do justly and love mercy (Yeah), and we will place at the head of the southern states governors who will, who have felt not only the tang of the human, but the glow of the Divine.

Give us the ballot (Yes), and we will quietly and nonviolently, without rancor or bitterness, implement the Supreme Court's decision of May seventeenth, 1954. (That's right).

King regards the ballot as a symbol of equality and dignity, but also as a tool for the political redress of grievances, an actual means by which disenfranchised citizens, in this instance Black citizens, can improve the conditions of their lives through the exercise of political power.

It is this dimension of voting rights that is often given insufficient attention by those who center their advocacy on the essential, but insufficient, moral claim. And it is this dimension of voting rights that might actually move people now to act, to defend their rights and to exercise them in 2022 and 2024--if they can be helped to see what was obvious to King: that the vote, if treated as one crucial democratic means of political mobilization among others, has the power to bring real change, and the denial of the vote is a way for those in power to prevent such change.

If we are have to have any hope of turning back the tide of Republican authoritarianism, masses of voters who are now skeptical or indifferent need to be convinced of this.

King, in emphasizing in his speech the practical dimension of voting rights, was continuing a long rhetorical tradition in the struggle for Black civil rights.

A very similar argument can be found in a brilliant though underappreciated essay by Ida B. Wells-Barnett, "How Enfranchisement Stops Lynchings," published in June 1910 in Original Rights Magazine.

Wells-Barnett begins, in her very first sentence, by observing that "the Negro question has been present with the American people . . . since 1619." Briefly describing the violence and degradation associated with the enslavement of Black people, she quickly arrives at the disturbing truth that slavery's abolition did not produce freedom for Blacks:

The flower of the nineteenth century civilization was the abolition of slavery, and the enfranchisement of all manhood. Here at last was squaring of practice with precept, with true democracy, with the Declaration of Independence and with the Golden Rule. The reproach and disgrace of the twentieth century is that the whole of the American people have permitted a part to nullify this glorious achievement, and make the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution playthings, a mockery and a byword; an absolute dead letter in the Constitution of the United States.

Recounting the betrayal of the promise of Reconstruction, Wells-Barnett immediately draws the connection between the practical sufferings of Black citizens and the denial of their right to vote:

The Negro has been given separate and inferior schools, because he has no ballot. He therefore cannot protest such legislation by choosing other law makers, or retiring to private life those who legislate against his interests . . . His only weapon of defense has been taken from him by legal enactment in all of the old Confederacy--and the United States Government, a consenting Saul stands by holding the clothes of those who stone and burn him to death literally and politically.

With no sacredness of the ballot there can be no sacredness of human life itself. For if the strong can take the week man's ballot when it suits his purpose to do so, he will take his life also. Having successfully swept aside all the constitutional safeguards to the ballot, it is the smallest of small matters for the South to sweep aside its own safeguards to human life . . . Therefore, the more complete the disenfranchisement, the more frequent and horrible has been the hangings, shootings and burnings.

Lynching, of course, is the evil that occupies her attention, here as elsewhere. But the central argument of this essay is not that lynching is the awful consequence of American racism, but that lynching, the most extreme form of injustice, can be stopped by the enfranchisement of Black citizens. And her prime example is her own experience, as an investigative reporter and as an activist, in the fight against lynching in Illinois, the state in which she lived.

Reviewing the wave of lynchings in that state, including the notorious Springfield race riot of 1908, Wells-Barnett focuses on the 1909 lynching of a Black man, William "Froggie" James, in Cairo, Illinois, and on the political response to the event, which she had helped to mobilize through her public writing. Her point: the Black citizens of Illinois organized themselves, exercised their voting rights in that state, and they made a difference. She points out that "The Negroes of Illinois have taken counsel together for a number of years over Illinois' increased lynching record. They elected one of their own to the state legislature in 1904, who secured the passage of a bill which provided for the suppression of mob violence." And she then points out that this bill-- the Mob Violence Act of 1905--became the basis on which the Republican Governor of the state, Charles Deneen, a supporter of civil rights, acted decisively to fire the Cairo sheriff, and to declare, loudly, that "mob violence has no place in Illinois."

Wells-Barnett quotes at length from the powerful statement made by Governor Deneen, in which he declared that he would use his executive authority to enforce civil rights law and to punish those who violate it. No Pollyanna, she notes that this declaration has provoked resistance. She nonetheless argues that it appears to represent the "death blow" to lynching in the state.

Her message: what is happening in Illinois can happen everywhere in the country: if the enfranchisement of Blacks, as announced in the Constitution, is protected, then Blacks can use their voting power to contest and end racial injustice. A very big "if." But one that she believes achievable.

Indeed, like King, Wells-Barnett herself was reiterating a long-standing argument for Black enfranchisement, that had earlier been made by none other than Frederick Douglass himself. In his 1872 "Give Us the Freedom Intended for Us," one of his many withering critiques of the failings of Reconstruction, Douglass stated this sharply:

The elective franchise without protection in its exercise amounts to almost nothing in the hands of a minority with a vast majority determined that no exercise of it shall be made by the minority. Freedom from the auction black and from legal claim as property is of no benefit to the colored man without the means of protecting his rights. The black man is not a free American citizen in the sense that a white man is a free American citizen." The reason? Without the right to vote, "he cannot protect himself against encroachments upon [his] rights and privileges.

The denial of the right to vote, Douglass insists, is an affront to the dignity of Black citizens. But perhaps even more importantly, it is a way of enforcing a virtual enslavement, by depriving Blacks of the "means of protection" necessary to secure their safety, their education, their property, and their livelihoods.

The idea that voting rights are an essential means of citizen self-protection has been central a central theme for a great many democratic activists in U.S. history.

Susan B. Anthony, in her famous 1872 speech, "Is it a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?," rehearses a litany of ways that the denial of voting rights on the basis of sex sustains the general subordination of women, and disenfranchises them from speaking and acting for themselves in the broader public world. "We all know," she insists, "that the crowning glory of every citizen of the United States is, that he can either give or withhold his vote from every law and every legislator under the government. . . . There is, and can be, but one safe principle of government-equal rights to all. And any and every discrimination against any class, whether on account of color, race, nativity, sex, property, culture, can but imbitter and disaffect that class, and thereby endanger the safety of the whole people."

Perhaps the most ringing statement of this theme can be found in Eugene V. Debs's 1894 speech, "Liberty: Speech at Battery D, Chicago."

Speaking to a crowd of supporters after his release from a six-month jail sentence for his activities, as leader of the American Railway Union, during the Pullman strike, Debs observed: "I stand in your presence stripped of my constitutional rights as a freeman and shorn of the most sacred prerogatives of American citizenship, and what is true of myself is true of every other citizen who has the temerity to protest against corporation rule or question the absolute sway of the money power. It is not law nor the administration of law of which I complain. It is the flagrant violation of the Constitution, the total abrogation of law and the usurpation of judicial and despotic power. . ."

But he then turns, on a dime, to the political potential possessed by ordinary American citizens:

Above all, what is the duty of American workingmen whose liberties have been placed in peril? They are not hereditary bondsmen. Their fathers were free born - their sovereignty none denied and their children yet have the ballot. It has been called "a weapon that executes a free man's will as lighting does the will of God." It is a metaphor pregnant with life and truth. There is nothing in our government it cannot remove or amend. It can make and unmake presidents and congresses and courts. It can abolish unjust laws and consign to eternal odium and oblivion unjust judges, strip from them their robes and gowns and send them forth unclean as lepers to bear the burden of merited obloquy as Cain with the mark of a murderer. It can sweep away trusts, syndicates, corporations, monopolies, and every other abnormal development of the money power designed to abridge the liberties of workingmen and enslave them by the degradation incident to poverty and enforced idleness, as cyclones scatter the leaves of the forest. The ballot can do all this and more. It can give our civilization its crowning glory - the cooperative commonwealth. . . ."

Debs was a brilliant orator. He was exaggerating the power of the ballot, and he knew it, and his audience, still bitter with the memory of the Pullman strike's suppression, knew it too. But only by half. Because while the ballot surely cannot produce results with the certainty, and the immediacy, of "God's lighting"--the performative "Let there be light!""--the right to vote is a right that can be mobilized by those in need to make themselves heard, and to pressure politicians to listen, and to punish those who refuse to listen.

As Michael Waldman argues in his excellent 2016 book, The Fight to Vote, the struggle of disenfranchised groups to obtain, protect, and exercise the right to vote has been perhaps the defining thread of U.S. history. And this struggle has always involved both a moral claim and a practical demand to be heard and to be heeded, a demand that the problems of ordinary citizens be addressed by the government that claims to govern in their name.

NYU's Brennan Center for Justice, where Waldman has long served as president, is one of a number of civil society organizations currently leading the fight to educate the public about the threats to voting rights and democratic elections and the ways to counter these threats. If you go to its website today, you will encounter a public appeal for support--and this support is one very worthy investment--headlined with these words, in boldface: "It's Now or Never for Democracy."

Truer words have never been spoken.

The Republican party is doing its very best to bend the "moral arc of the universe" towards reaction and injustice. It will take real effort to keep Republican efforts at bay much less to move things forward.

And as we celebrate the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr., we should remember that King's courageous effort to make real the promise of American democracy always joined the moral claim to equal voting rights with the practical understanding that voting rights were a means and an instrument whereby ordinary citizens could mobilize political power so as to make the world a better place to live decent and meaningful lives.

Only by remembering this lesson, and acting on it, might it be possible to turn back a rising tide of authoritarianism in 2022 and 2024.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Voting rights and electoral fairness are currently the most contested issues in our extremely polarized political system. And the best way to advance these essential values is to make clear the inextricable link between the moral and the practical.

The Republican party, and tens of millions of those citizens who support it, are now following the logic of the "Stop the Steal" rhetoric of disgraced, twice-impeached, former President Trump. Maintaining that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen (but, miraculously, the many elections that they won were not stolen), and claiming that the Democrats are determined to commit election fraud in the future, they are committed to changing state elections laws to make it harder to vote and easier for their party leaders to overturn "stolen" elections. And they are also committed to opposing any effort to protect voting rights and non-partisan elections through federal legislation.

"We should remember that King's courageous effort to make real the promise of American democracy always joined the moral claim to equal voting rights with the practical understanding that voting rights were a means and an instrument whereby ordinary citizens could mobilize political power so as to make the world a better place to live decent and meaningful lives."

They must be defeated. Defeating them is necessary in order to "vindicate" the slim "victory" that Democrats claimed in 2020, and to make possible more decisive victories in the future. Failure is not an option if even the most threadbare version of constitutional democracy is to be saved.

The approach of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day has been an especially appropriate moment for the question move to center stage. In their addresses last week, both President Biden and Vice President Harris made explicit the connection between current Republican voter suppression efforts and the history of Jim Crow, and between Democratic support for federal legislation--the John Lewis Act, the Freedom to Vote Act--and the civil rights movement.

Toda's commemoration of King is a wonderful occasion to recall his own emphasis on the centrality of voting rights. Colbert I. King does a great job of this in his recent Washington Post piece, "Martin Luther King Jr.'s words on voting rights resonate all too well today."

The piece, which centers on King's important 1957 speech, "Give Us the Ballot," powerfully emphasizes the moral demand for human dignity underlying King's advocacy. But it misses one important element of King's actual defense of voting rights: the indissoluble link between voting rights and all other rights, and the way that without the right to vote, citizens are disabled from voicing their concerns and from protecting themselves from abuse and injustice.

In his speech, King insists that "The denial of this sacred right is a tragic betrayal of the highest mandates of our democratic tradition." He then immediately segues to the consequences that would follow from the protection of voting rights:

Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights.

Give us the ballot (Yes), and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South (All right) and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

Give us the ballot (Give us the ballot), and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs (Yeah) into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens.

Give us the ballot (Give us the ballot), and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill (All right now) and send to the sacred halls of Congress men who will not sign a "Southern Manifesto" because of their devotion to the manifesto of justice. (Tell 'em about it)

Give us the ballot (Yeah), and we will place judges on the benches of the South who will do justly and love mercy (Yeah), and we will place at the head of the southern states governors who will, who have felt not only the tang of the human, but the glow of the Divine.

Give us the ballot (Yes), and we will quietly and nonviolently, without rancor or bitterness, implement the Supreme Court's decision of May seventeenth, 1954. (That's right).

King regards the ballot as a symbol of equality and dignity, but also as a tool for the political redress of grievances, an actual means by which disenfranchised citizens, in this instance Black citizens, can improve the conditions of their lives through the exercise of political power.

It is this dimension of voting rights that is often given insufficient attention by those who center their advocacy on the essential, but insufficient, moral claim. And it is this dimension of voting rights that might actually move people now to act, to defend their rights and to exercise them in 2022 and 2024--if they can be helped to see what was obvious to King: that the vote, if treated as one crucial democratic means of political mobilization among others, has the power to bring real change, and the denial of the vote is a way for those in power to prevent such change.

If we are have to have any hope of turning back the tide of Republican authoritarianism, masses of voters who are now skeptical or indifferent need to be convinced of this.

King, in emphasizing in his speech the practical dimension of voting rights, was continuing a long rhetorical tradition in the struggle for Black civil rights.

A very similar argument can be found in a brilliant though underappreciated essay by Ida B. Wells-Barnett, "How Enfranchisement Stops Lynchings," published in June 1910 in Original Rights Magazine.

Wells-Barnett begins, in her very first sentence, by observing that "the Negro question has been present with the American people . . . since 1619." Briefly describing the violence and degradation associated with the enslavement of Black people, she quickly arrives at the disturbing truth that slavery's abolition did not produce freedom for Blacks:

The flower of the nineteenth century civilization was the abolition of slavery, and the enfranchisement of all manhood. Here at last was squaring of practice with precept, with true democracy, with the Declaration of Independence and with the Golden Rule. The reproach and disgrace of the twentieth century is that the whole of the American people have permitted a part to nullify this glorious achievement, and make the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution playthings, a mockery and a byword; an absolute dead letter in the Constitution of the United States.

Recounting the betrayal of the promise of Reconstruction, Wells-Barnett immediately draws the connection between the practical sufferings of Black citizens and the denial of their right to vote:

The Negro has been given separate and inferior schools, because he has no ballot. He therefore cannot protest such legislation by choosing other law makers, or retiring to private life those who legislate against his interests . . . His only weapon of defense has been taken from him by legal enactment in all of the old Confederacy--and the United States Government, a consenting Saul stands by holding the clothes of those who stone and burn him to death literally and politically.

With no sacredness of the ballot there can be no sacredness of human life itself. For if the strong can take the week man's ballot when it suits his purpose to do so, he will take his life also. Having successfully swept aside all the constitutional safeguards to the ballot, it is the smallest of small matters for the South to sweep aside its own safeguards to human life . . . Therefore, the more complete the disenfranchisement, the more frequent and horrible has been the hangings, shootings and burnings.

Lynching, of course, is the evil that occupies her attention, here as elsewhere. But the central argument of this essay is not that lynching is the awful consequence of American racism, but that lynching, the most extreme form of injustice, can be stopped by the enfranchisement of Black citizens. And her prime example is her own experience, as an investigative reporter and as an activist, in the fight against lynching in Illinois, the state in which she lived.

Reviewing the wave of lynchings in that state, including the notorious Springfield race riot of 1908, Wells-Barnett focuses on the 1909 lynching of a Black man, William "Froggie" James, in Cairo, Illinois, and on the political response to the event, which she had helped to mobilize through her public writing. Her point: the Black citizens of Illinois organized themselves, exercised their voting rights in that state, and they made a difference. She points out that "The Negroes of Illinois have taken counsel together for a number of years over Illinois' increased lynching record. They elected one of their own to the state legislature in 1904, who secured the passage of a bill which provided for the suppression of mob violence." And she then points out that this bill-- the Mob Violence Act of 1905--became the basis on which the Republican Governor of the state, Charles Deneen, a supporter of civil rights, acted decisively to fire the Cairo sheriff, and to declare, loudly, that "mob violence has no place in Illinois."

Wells-Barnett quotes at length from the powerful statement made by Governor Deneen, in which he declared that he would use his executive authority to enforce civil rights law and to punish those who violate it. No Pollyanna, she notes that this declaration has provoked resistance. She nonetheless argues that it appears to represent the "death blow" to lynching in the state.

Her message: what is happening in Illinois can happen everywhere in the country: if the enfranchisement of Blacks, as announced in the Constitution, is protected, then Blacks can use their voting power to contest and end racial injustice. A very big "if." But one that she believes achievable.

Indeed, like King, Wells-Barnett herself was reiterating a long-standing argument for Black enfranchisement, that had earlier been made by none other than Frederick Douglass himself. In his 1872 "Give Us the Freedom Intended for Us," one of his many withering critiques of the failings of Reconstruction, Douglass stated this sharply:

The elective franchise without protection in its exercise amounts to almost nothing in the hands of a minority with a vast majority determined that no exercise of it shall be made by the minority. Freedom from the auction black and from legal claim as property is of no benefit to the colored man without the means of protecting his rights. The black man is not a free American citizen in the sense that a white man is a free American citizen." The reason? Without the right to vote, "he cannot protect himself against encroachments upon [his] rights and privileges.

The denial of the right to vote, Douglass insists, is an affront to the dignity of Black citizens. But perhaps even more importantly, it is a way of enforcing a virtual enslavement, by depriving Blacks of the "means of protection" necessary to secure their safety, their education, their property, and their livelihoods.

The idea that voting rights are an essential means of citizen self-protection has been central a central theme for a great many democratic activists in U.S. history.

Susan B. Anthony, in her famous 1872 speech, "Is it a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?," rehearses a litany of ways that the denial of voting rights on the basis of sex sustains the general subordination of women, and disenfranchises them from speaking and acting for themselves in the broader public world. "We all know," she insists, "that the crowning glory of every citizen of the United States is, that he can either give or withhold his vote from every law and every legislator under the government. . . . There is, and can be, but one safe principle of government-equal rights to all. And any and every discrimination against any class, whether on account of color, race, nativity, sex, property, culture, can but imbitter and disaffect that class, and thereby endanger the safety of the whole people."

Perhaps the most ringing statement of this theme can be found in Eugene V. Debs's 1894 speech, "Liberty: Speech at Battery D, Chicago."

Speaking to a crowd of supporters after his release from a six-month jail sentence for his activities, as leader of the American Railway Union, during the Pullman strike, Debs observed: "I stand in your presence stripped of my constitutional rights as a freeman and shorn of the most sacred prerogatives of American citizenship, and what is true of myself is true of every other citizen who has the temerity to protest against corporation rule or question the absolute sway of the money power. It is not law nor the administration of law of which I complain. It is the flagrant violation of the Constitution, the total abrogation of law and the usurpation of judicial and despotic power. . ."

But he then turns, on a dime, to the political potential possessed by ordinary American citizens:

Above all, what is the duty of American workingmen whose liberties have been placed in peril? They are not hereditary bondsmen. Their fathers were free born - their sovereignty none denied and their children yet have the ballot. It has been called "a weapon that executes a free man's will as lighting does the will of God." It is a metaphor pregnant with life and truth. There is nothing in our government it cannot remove or amend. It can make and unmake presidents and congresses and courts. It can abolish unjust laws and consign to eternal odium and oblivion unjust judges, strip from them their robes and gowns and send them forth unclean as lepers to bear the burden of merited obloquy as Cain with the mark of a murderer. It can sweep away trusts, syndicates, corporations, monopolies, and every other abnormal development of the money power designed to abridge the liberties of workingmen and enslave them by the degradation incident to poverty and enforced idleness, as cyclones scatter the leaves of the forest. The ballot can do all this and more. It can give our civilization its crowning glory - the cooperative commonwealth. . . ."

Debs was a brilliant orator. He was exaggerating the power of the ballot, and he knew it, and his audience, still bitter with the memory of the Pullman strike's suppression, knew it too. But only by half. Because while the ballot surely cannot produce results with the certainty, and the immediacy, of "God's lighting"--the performative "Let there be light!""--the right to vote is a right that can be mobilized by those in need to make themselves heard, and to pressure politicians to listen, and to punish those who refuse to listen.

As Michael Waldman argues in his excellent 2016 book, The Fight to Vote, the struggle of disenfranchised groups to obtain, protect, and exercise the right to vote has been perhaps the defining thread of U.S. history. And this struggle has always involved both a moral claim and a practical demand to be heard and to be heeded, a demand that the problems of ordinary citizens be addressed by the government that claims to govern in their name.

NYU's Brennan Center for Justice, where Waldman has long served as president, is one of a number of civil society organizations currently leading the fight to educate the public about the threats to voting rights and democratic elections and the ways to counter these threats. If you go to its website today, you will encounter a public appeal for support--and this support is one very worthy investment--headlined with these words, in boldface: "It's Now or Never for Democracy."

Truer words have never been spoken.

The Republican party is doing its very best to bend the "moral arc of the universe" towards reaction and injustice. It will take real effort to keep Republican efforts at bay much less to move things forward.

And as we celebrate the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr., we should remember that King's courageous effort to make real the promise of American democracy always joined the moral claim to equal voting rights with the practical understanding that voting rights were a means and an instrument whereby ordinary citizens could mobilize political power so as to make the world a better place to live decent and meaningful lives.

Only by remembering this lesson, and acting on it, might it be possible to turn back a rising tide of authoritarianism in 2022 and 2024.

Voting rights and electoral fairness are currently the most contested issues in our extremely polarized political system. And the best way to advance these essential values is to make clear the inextricable link between the moral and the practical.

The Republican party, and tens of millions of those citizens who support it, are now following the logic of the "Stop the Steal" rhetoric of disgraced, twice-impeached, former President Trump. Maintaining that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen (but, miraculously, the many elections that they won were not stolen), and claiming that the Democrats are determined to commit election fraud in the future, they are committed to changing state elections laws to make it harder to vote and easier for their party leaders to overturn "stolen" elections. And they are also committed to opposing any effort to protect voting rights and non-partisan elections through federal legislation.

"We should remember that King's courageous effort to make real the promise of American democracy always joined the moral claim to equal voting rights with the practical understanding that voting rights were a means and an instrument whereby ordinary citizens could mobilize political power so as to make the world a better place to live decent and meaningful lives."

They must be defeated. Defeating them is necessary in order to "vindicate" the slim "victory" that Democrats claimed in 2020, and to make possible more decisive victories in the future. Failure is not an option if even the most threadbare version of constitutional democracy is to be saved.

The approach of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day has been an especially appropriate moment for the question move to center stage. In their addresses last week, both President Biden and Vice President Harris made explicit the connection between current Republican voter suppression efforts and the history of Jim Crow, and between Democratic support for federal legislation--the John Lewis Act, the Freedom to Vote Act--and the civil rights movement.

Toda's commemoration of King is a wonderful occasion to recall his own emphasis on the centrality of voting rights. Colbert I. King does a great job of this in his recent Washington Post piece, "Martin Luther King Jr.'s words on voting rights resonate all too well today."

The piece, which centers on King's important 1957 speech, "Give Us the Ballot," powerfully emphasizes the moral demand for human dignity underlying King's advocacy. But it misses one important element of King's actual defense of voting rights: the indissoluble link between voting rights and all other rights, and the way that without the right to vote, citizens are disabled from voicing their concerns and from protecting themselves from abuse and injustice.

In his speech, King insists that "The denial of this sacred right is a tragic betrayal of the highest mandates of our democratic tradition." He then immediately segues to the consequences that would follow from the protection of voting rights:

Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights.

Give us the ballot (Yes), and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South (All right) and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

Give us the ballot (Give us the ballot), and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs (Yeah) into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens.

Give us the ballot (Give us the ballot), and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill (All right now) and send to the sacred halls of Congress men who will not sign a "Southern Manifesto" because of their devotion to the manifesto of justice. (Tell 'em about it)

Give us the ballot (Yeah), and we will place judges on the benches of the South who will do justly and love mercy (Yeah), and we will place at the head of the southern states governors who will, who have felt not only the tang of the human, but the glow of the Divine.

Give us the ballot (Yes), and we will quietly and nonviolently, without rancor or bitterness, implement the Supreme Court's decision of May seventeenth, 1954. (That's right).

King regards the ballot as a symbol of equality and dignity, but also as a tool for the political redress of grievances, an actual means by which disenfranchised citizens, in this instance Black citizens, can improve the conditions of their lives through the exercise of political power.

It is this dimension of voting rights that is often given insufficient attention by those who center their advocacy on the essential, but insufficient, moral claim. And it is this dimension of voting rights that might actually move people now to act, to defend their rights and to exercise them in 2022 and 2024--if they can be helped to see what was obvious to King: that the vote, if treated as one crucial democratic means of political mobilization among others, has the power to bring real change, and the denial of the vote is a way for those in power to prevent such change.

If we are have to have any hope of turning back the tide of Republican authoritarianism, masses of voters who are now skeptical or indifferent need to be convinced of this.

King, in emphasizing in his speech the practical dimension of voting rights, was continuing a long rhetorical tradition in the struggle for Black civil rights.

A very similar argument can be found in a brilliant though underappreciated essay by Ida B. Wells-Barnett, "How Enfranchisement Stops Lynchings," published in June 1910 in Original Rights Magazine.

Wells-Barnett begins, in her very first sentence, by observing that "the Negro question has been present with the American people . . . since 1619." Briefly describing the violence and degradation associated with the enslavement of Black people, she quickly arrives at the disturbing truth that slavery's abolition did not produce freedom for Blacks:

The flower of the nineteenth century civilization was the abolition of slavery, and the enfranchisement of all manhood. Here at last was squaring of practice with precept, with true democracy, with the Declaration of Independence and with the Golden Rule. The reproach and disgrace of the twentieth century is that the whole of the American people have permitted a part to nullify this glorious achievement, and make the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution playthings, a mockery and a byword; an absolute dead letter in the Constitution of the United States.

Recounting the betrayal of the promise of Reconstruction, Wells-Barnett immediately draws the connection between the practical sufferings of Black citizens and the denial of their right to vote:

The Negro has been given separate and inferior schools, because he has no ballot. He therefore cannot protest such legislation by choosing other law makers, or retiring to private life those who legislate against his interests . . . His only weapon of defense has been taken from him by legal enactment in all of the old Confederacy--and the United States Government, a consenting Saul stands by holding the clothes of those who stone and burn him to death literally and politically.

With no sacredness of the ballot there can be no sacredness of human life itself. For if the strong can take the week man's ballot when it suits his purpose to do so, he will take his life also. Having successfully swept aside all the constitutional safeguards to the ballot, it is the smallest of small matters for the South to sweep aside its own safeguards to human life . . . Therefore, the more complete the disenfranchisement, the more frequent and horrible has been the hangings, shootings and burnings.

Lynching, of course, is the evil that occupies her attention, here as elsewhere. But the central argument of this essay is not that lynching is the awful consequence of American racism, but that lynching, the most extreme form of injustice, can be stopped by the enfranchisement of Black citizens. And her prime example is her own experience, as an investigative reporter and as an activist, in the fight against lynching in Illinois, the state in which she lived.

Reviewing the wave of lynchings in that state, including the notorious Springfield race riot of 1908, Wells-Barnett focuses on the 1909 lynching of a Black man, William "Froggie" James, in Cairo, Illinois, and on the political response to the event, which she had helped to mobilize through her public writing. Her point: the Black citizens of Illinois organized themselves, exercised their voting rights in that state, and they made a difference. She points out that "The Negroes of Illinois have taken counsel together for a number of years over Illinois' increased lynching record. They elected one of their own to the state legislature in 1904, who secured the passage of a bill which provided for the suppression of mob violence." And she then points out that this bill-- the Mob Violence Act of 1905--became the basis on which the Republican Governor of the state, Charles Deneen, a supporter of civil rights, acted decisively to fire the Cairo sheriff, and to declare, loudly, that "mob violence has no place in Illinois."

Wells-Barnett quotes at length from the powerful statement made by Governor Deneen, in which he declared that he would use his executive authority to enforce civil rights law and to punish those who violate it. No Pollyanna, she notes that this declaration has provoked resistance. She nonetheless argues that it appears to represent the "death blow" to lynching in the state.

Her message: what is happening in Illinois can happen everywhere in the country: if the enfranchisement of Blacks, as announced in the Constitution, is protected, then Blacks can use their voting power to contest and end racial injustice. A very big "if." But one that she believes achievable.

Indeed, like King, Wells-Barnett herself was reiterating a long-standing argument for Black enfranchisement, that had earlier been made by none other than Frederick Douglass himself. In his 1872 "Give Us the Freedom Intended for Us," one of his many withering critiques of the failings of Reconstruction, Douglass stated this sharply:

The elective franchise without protection in its exercise amounts to almost nothing in the hands of a minority with a vast majority determined that no exercise of it shall be made by the minority. Freedom from the auction black and from legal claim as property is of no benefit to the colored man without the means of protecting his rights. The black man is not a free American citizen in the sense that a white man is a free American citizen." The reason? Without the right to vote, "he cannot protect himself against encroachments upon [his] rights and privileges.

The denial of the right to vote, Douglass insists, is an affront to the dignity of Black citizens. But perhaps even more importantly, it is a way of enforcing a virtual enslavement, by depriving Blacks of the "means of protection" necessary to secure their safety, their education, their property, and their livelihoods.

The idea that voting rights are an essential means of citizen self-protection has been central a central theme for a great many democratic activists in U.S. history.

Susan B. Anthony, in her famous 1872 speech, "Is it a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?," rehearses a litany of ways that the denial of voting rights on the basis of sex sustains the general subordination of women, and disenfranchises them from speaking and acting for themselves in the broader public world. "We all know," she insists, "that the crowning glory of every citizen of the United States is, that he can either give or withhold his vote from every law and every legislator under the government. . . . There is, and can be, but one safe principle of government-equal rights to all. And any and every discrimination against any class, whether on account of color, race, nativity, sex, property, culture, can but imbitter and disaffect that class, and thereby endanger the safety of the whole people."

Perhaps the most ringing statement of this theme can be found in Eugene V. Debs's 1894 speech, "Liberty: Speech at Battery D, Chicago."

Speaking to a crowd of supporters after his release from a six-month jail sentence for his activities, as leader of the American Railway Union, during the Pullman strike, Debs observed: "I stand in your presence stripped of my constitutional rights as a freeman and shorn of the most sacred prerogatives of American citizenship, and what is true of myself is true of every other citizen who has the temerity to protest against corporation rule or question the absolute sway of the money power. It is not law nor the administration of law of which I complain. It is the flagrant violation of the Constitution, the total abrogation of law and the usurpation of judicial and despotic power. . ."

But he then turns, on a dime, to the political potential possessed by ordinary American citizens:

Above all, what is the duty of American workingmen whose liberties have been placed in peril? They are not hereditary bondsmen. Their fathers were free born - their sovereignty none denied and their children yet have the ballot. It has been called "a weapon that executes a free man's will as lighting does the will of God." It is a metaphor pregnant with life and truth. There is nothing in our government it cannot remove or amend. It can make and unmake presidents and congresses and courts. It can abolish unjust laws and consign to eternal odium and oblivion unjust judges, strip from them their robes and gowns and send them forth unclean as lepers to bear the burden of merited obloquy as Cain with the mark of a murderer. It can sweep away trusts, syndicates, corporations, monopolies, and every other abnormal development of the money power designed to abridge the liberties of workingmen and enslave them by the degradation incident to poverty and enforced idleness, as cyclones scatter the leaves of the forest. The ballot can do all this and more. It can give our civilization its crowning glory - the cooperative commonwealth. . . ."

Debs was a brilliant orator. He was exaggerating the power of the ballot, and he knew it, and his audience, still bitter with the memory of the Pullman strike's suppression, knew it too. But only by half. Because while the ballot surely cannot produce results with the certainty, and the immediacy, of "God's lighting"--the performative "Let there be light!""--the right to vote is a right that can be mobilized by those in need to make themselves heard, and to pressure politicians to listen, and to punish those who refuse to listen.

As Michael Waldman argues in his excellent 2016 book, The Fight to Vote, the struggle of disenfranchised groups to obtain, protect, and exercise the right to vote has been perhaps the defining thread of U.S. history. And this struggle has always involved both a moral claim and a practical demand to be heard and to be heeded, a demand that the problems of ordinary citizens be addressed by the government that claims to govern in their name.

NYU's Brennan Center for Justice, where Waldman has long served as president, is one of a number of civil society organizations currently leading the fight to educate the public about the threats to voting rights and democratic elections and the ways to counter these threats. If you go to its website today, you will encounter a public appeal for support--and this support is one very worthy investment--headlined with these words, in boldface: "It's Now or Never for Democracy."

Truer words have never been spoken.

The Republican party is doing its very best to bend the "moral arc of the universe" towards reaction and injustice. It will take real effort to keep Republican efforts at bay much less to move things forward.

And as we celebrate the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr., we should remember that King's courageous effort to make real the promise of American democracy always joined the moral claim to equal voting rights with the practical understanding that voting rights were a means and an instrument whereby ordinary citizens could mobilize political power so as to make the world a better place to live decent and meaningful lives.

Only by remembering this lesson, and acting on it, might it be possible to turn back a rising tide of authoritarianism in 2022 and 2024.