SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Derrick Davis, a member of West Virginia New Jobs Coalition, hangs up signage during a community gathering and job fair on April 8, 2021 in Charleston, West Virginia. (Photo: Emilee Chinn/Getty Images for Green New Deal Network)

Most of the data on the economy is looking very good these days. The number of weekly unemployment claims has fallen sharply. Levels are still high, but just over half the level we were seeing earlier this year. And, this is before all the moves by Republican governors to cut back benefits, so the decline reflects the availability of jobs, not more stringent eligibility.

Consumer spending has been rising rapidly, with the March and April levels both above where they were before the pandemic. Even restaurant sales have largely recovered. Adjusted for inflation, the April levels were just 2.7 percent below where they were in February, 2020.

"There has been some evidence that wages are increasing more rapidly in the lowest paying sectors, like hotels and restaurants. This is good news for these workers and it is not especially inflationary."

The housing market continues to be very strong, especially in lower priced areas. The increase in the Federal Housing Finance Administration's house price index from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021 was 16.0 percent in Wichita, KS, 15.8 percent in Buffalo, NY, 15.6 percent in Dayton, OH, 14.6 percent in Nashville, TN, and 13.8 percent in Gary, IN. By contrast, prices are up just 9.7 percent in the New York metro area and 6.5 percent in San Francisco.

It is too early to know if this is the start of a trend, where people take advantage of increased opportunities for remote work to live in lower cost, or whether it is a one-time blip. However, if the opportunities for increased remote work stay in place after pandemic is over, it is likely that more people will move to low-cost areas. This will both benefit those areas, by bringing in new consumers and taxpayers, and also the high cost areas, by relieving pressure on house prices.

Residential construction has also been very strong, running at close to 25 percent above the pre-pandemic pace. Starts did slow some in April, which is likely in past due to a shortage of materials, most importantly lumber. This should be alleviated in the months ahead.

Investment also is strong. New orders for capital goods are running more than 10 percent above the pre-pandemic level. This is noteworthy because it doesn't appear that the prospect of higher corporate income taxes is doing much to discourage new investment.

With the rapid growth we are now seeing across most sectors in the economy, many have raised concerns about inflation. We did see high inflation numbers in April. There are two main factors here. First, much of this is a bounce back effect, where the price of many items that plunged during the recession is now rebounding back to more normal levels. This is true in areas like hotels, airfares, and car insurance.

The other factor is that there are shortages in many areas as the economy is again getting up to steam. This is the case with lumber, where many mills shut down, anticipating a longer recession. It will take some time to get them up and running again. It is also the case with cars, where a shortage of semi-conductors, due to a fire at a plant in Japan, has hampered production. New car prices rose 0.5 percent in April, while used car prices rose an incredible 10.0 percent in the month, adding almost 0.3 percentage points to the CPI.

Both of these effects will be temporary. If we are to see sustained inflation then we really need a story where wage growth is substantially outpacing productivity growth. There is not the case at present. Wage growth has at best accelerated modestly, with the average hourly wage rising at an annual rate of 3.1 percent, comparing the last three months (February, March, April) with the prior three months (November, December, January).

This would not be the basis for real concerns with inflation, even if productivity had stayed on its pre-pandemic pace of just over 1.0 percent annually. However, productivity growth has accelerated sharply in the last year, rising 4.1 percent from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021. With GDP growth projected at close to 10 percent for the second quarter, we will almost certain add another strong quarter of productivity growth.

It is not plausible that we will sustain productivity growth of 4.0 percent, but if the pace falls back to 2.0 percent, instead of its pre-pandemic 1.0 percent rate, it is hard to see inflation becoming a problem. A 2.0 percent rate of productivity growth is consistent with 4.0 percent wage growth and 2.0 percent inflation.

There has been some evidence that wages are increasing more rapidly in the lowest paying sectors, like hotels and restaurants. This is good news for these workers and it is not especially inflationary. The average weekly earnings at the cutoff for the bottom decile is less than $500. Suppose this rises by $50. This would come to $2,500 a year. With 15 million workers in the bottom decile, that comes to less than $40 billion annually, less than 0.2 percent of GDP.

That would not be the sort of thing that is likely to set off an inflationary spiral, and we are also not likely to see wages for the bottom decile rise by 10 percent in the immediate future.

What About the Debt?

With the release of President Biden's new budget there were a slew of news stories warning about the large deficit and projected debt. The usual story about high levels of debt is that they will cause bond markets to panic and interest rates to soar.

Back in the Clinton and Obama years we were regularly regaled with stories about how the bond market vigilantes would send interest rates soaring if we didn't rein in the deficit. And of course, they would reward us with low interest rates if we were good boys and girls and got deficits down, usually by cutting spending.

It turns out that it didn't have as much to fear from higher interest rates as advertised. Ever since the Great Recession, long-term interest rates have consistently run well below the projections from the Congressional Budget Office and most other forecasters. The interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds was hovering near 2.7 percent just before the pandemic hit, in spite of the large tax cut induced deficits of the Trump years. That compares to rates that were typically well over 5.0 percent when we were running budget surpluses in the Clinton years.

Rates plunged after the pandemic hit and the Fed stepped in with its rescue package. Even now, with the large deficits resulting from the CARES Act and President Biden's recovery package, the rate remains near 1.6 percent.

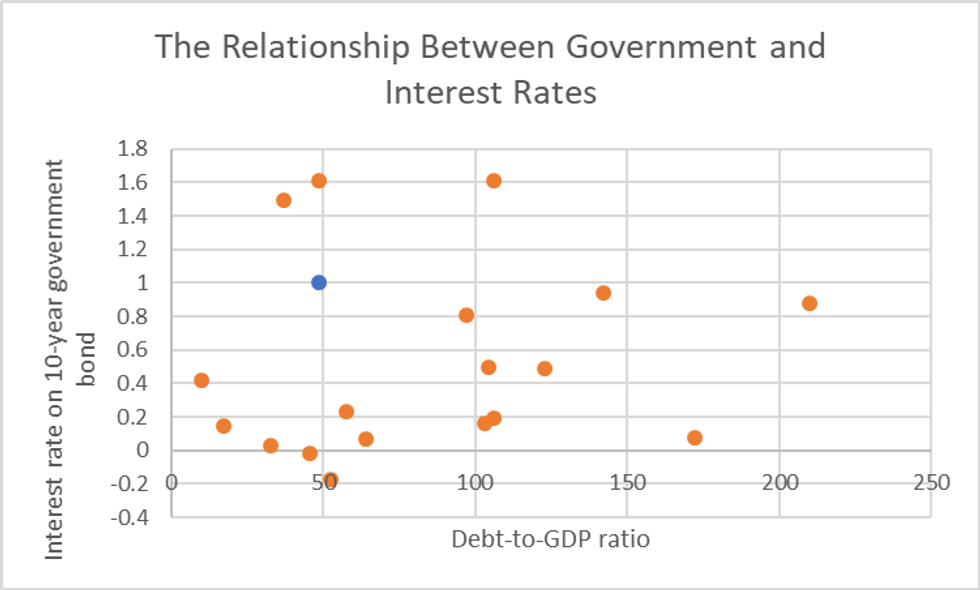

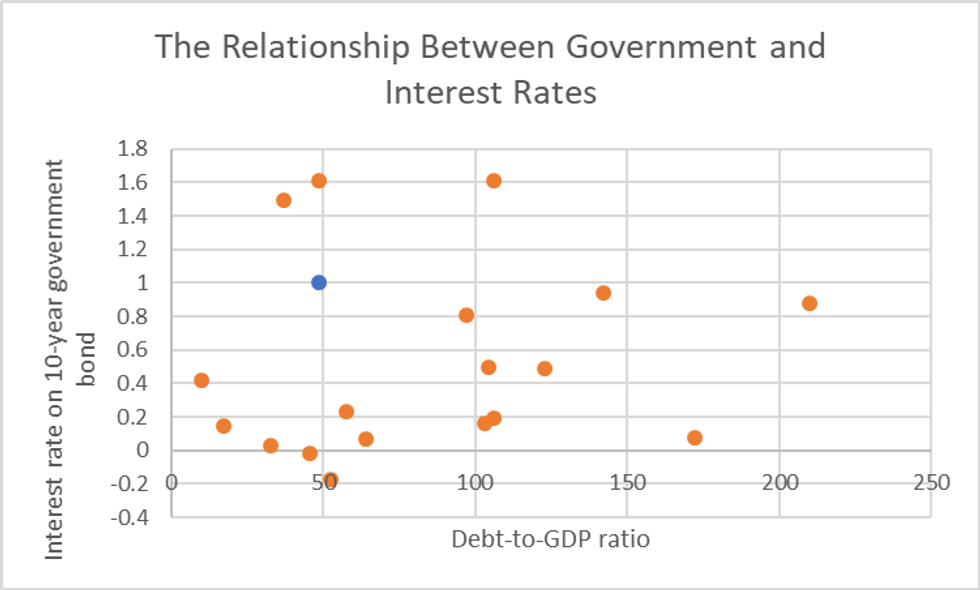

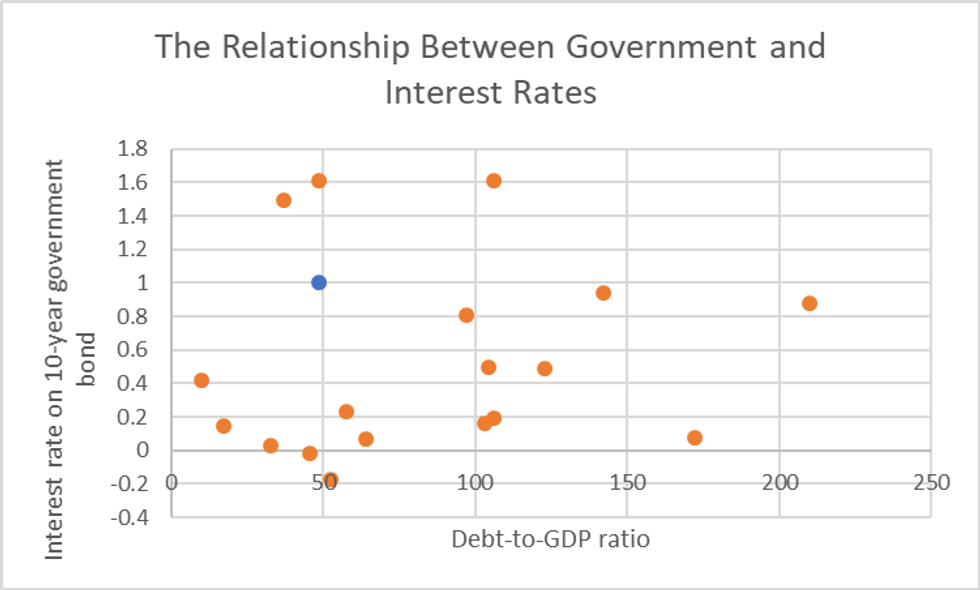

But the deficit hawks tell us this is all a temporary story. Soon the bond market vigilantes will get back on the job and send interest rates soaring. Perhaps this will happen at some point in the future, but there does not seem to be much evidence for it. The graph below shows the ratio of debt-to-GDP for most wealthy countries, compared with the interest rate on 10-year government bonds.

As can be seen, there is essentially no relationship between the two. Many countries with much larger debt-to-GDP ratios have far lower interest rates on their long-term bond. Japan takes the prize here with a debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 170 percent and an interest rate on its long-term bonds of less than 0.1 percent. However, many other countries with far higher debt-to-GDP ratios than the United States, including France, Belgium, and Greece, have much lower interest rates on their government debt.

In short, it doesn't seem like the deficit hawks have much of a case. To be clear, there is a real concern that the boost to the economy from the Biden recovery package may go to far and lead to problems with inflation. I have argued before that I think this risk is limited, and one well worth taking given the political obstacles Biden will face in getting future packages approved by Congress.

But this issue is very different from the concern that excessive debt will cause a flight from U.S. government bonds and send interest rates soaring. This one seems more a scare story designed to fool children rather than serious economic analysis.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Most of the data on the economy is looking very good these days. The number of weekly unemployment claims has fallen sharply. Levels are still high, but just over half the level we were seeing earlier this year. And, this is before all the moves by Republican governors to cut back benefits, so the decline reflects the availability of jobs, not more stringent eligibility.

Consumer spending has been rising rapidly, with the March and April levels both above where they were before the pandemic. Even restaurant sales have largely recovered. Adjusted for inflation, the April levels were just 2.7 percent below where they were in February, 2020.

"There has been some evidence that wages are increasing more rapidly in the lowest paying sectors, like hotels and restaurants. This is good news for these workers and it is not especially inflationary."

The housing market continues to be very strong, especially in lower priced areas. The increase in the Federal Housing Finance Administration's house price index from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021 was 16.0 percent in Wichita, KS, 15.8 percent in Buffalo, NY, 15.6 percent in Dayton, OH, 14.6 percent in Nashville, TN, and 13.8 percent in Gary, IN. By contrast, prices are up just 9.7 percent in the New York metro area and 6.5 percent in San Francisco.

It is too early to know if this is the start of a trend, where people take advantage of increased opportunities for remote work to live in lower cost, or whether it is a one-time blip. However, if the opportunities for increased remote work stay in place after pandemic is over, it is likely that more people will move to low-cost areas. This will both benefit those areas, by bringing in new consumers and taxpayers, and also the high cost areas, by relieving pressure on house prices.

Residential construction has also been very strong, running at close to 25 percent above the pre-pandemic pace. Starts did slow some in April, which is likely in past due to a shortage of materials, most importantly lumber. This should be alleviated in the months ahead.

Investment also is strong. New orders for capital goods are running more than 10 percent above the pre-pandemic level. This is noteworthy because it doesn't appear that the prospect of higher corporate income taxes is doing much to discourage new investment.

With the rapid growth we are now seeing across most sectors in the economy, many have raised concerns about inflation. We did see high inflation numbers in April. There are two main factors here. First, much of this is a bounce back effect, where the price of many items that plunged during the recession is now rebounding back to more normal levels. This is true in areas like hotels, airfares, and car insurance.

The other factor is that there are shortages in many areas as the economy is again getting up to steam. This is the case with lumber, where many mills shut down, anticipating a longer recession. It will take some time to get them up and running again. It is also the case with cars, where a shortage of semi-conductors, due to a fire at a plant in Japan, has hampered production. New car prices rose 0.5 percent in April, while used car prices rose an incredible 10.0 percent in the month, adding almost 0.3 percentage points to the CPI.

Both of these effects will be temporary. If we are to see sustained inflation then we really need a story where wage growth is substantially outpacing productivity growth. There is not the case at present. Wage growth has at best accelerated modestly, with the average hourly wage rising at an annual rate of 3.1 percent, comparing the last three months (February, March, April) with the prior three months (November, December, January).

This would not be the basis for real concerns with inflation, even if productivity had stayed on its pre-pandemic pace of just over 1.0 percent annually. However, productivity growth has accelerated sharply in the last year, rising 4.1 percent from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021. With GDP growth projected at close to 10 percent for the second quarter, we will almost certain add another strong quarter of productivity growth.

It is not plausible that we will sustain productivity growth of 4.0 percent, but if the pace falls back to 2.0 percent, instead of its pre-pandemic 1.0 percent rate, it is hard to see inflation becoming a problem. A 2.0 percent rate of productivity growth is consistent with 4.0 percent wage growth and 2.0 percent inflation.

There has been some evidence that wages are increasing more rapidly in the lowest paying sectors, like hotels and restaurants. This is good news for these workers and it is not especially inflationary. The average weekly earnings at the cutoff for the bottom decile is less than $500. Suppose this rises by $50. This would come to $2,500 a year. With 15 million workers in the bottom decile, that comes to less than $40 billion annually, less than 0.2 percent of GDP.

That would not be the sort of thing that is likely to set off an inflationary spiral, and we are also not likely to see wages for the bottom decile rise by 10 percent in the immediate future.

What About the Debt?

With the release of President Biden's new budget there were a slew of news stories warning about the large deficit and projected debt. The usual story about high levels of debt is that they will cause bond markets to panic and interest rates to soar.

Back in the Clinton and Obama years we were regularly regaled with stories about how the bond market vigilantes would send interest rates soaring if we didn't rein in the deficit. And of course, they would reward us with low interest rates if we were good boys and girls and got deficits down, usually by cutting spending.

It turns out that it didn't have as much to fear from higher interest rates as advertised. Ever since the Great Recession, long-term interest rates have consistently run well below the projections from the Congressional Budget Office and most other forecasters. The interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds was hovering near 2.7 percent just before the pandemic hit, in spite of the large tax cut induced deficits of the Trump years. That compares to rates that were typically well over 5.0 percent when we were running budget surpluses in the Clinton years.

Rates plunged after the pandemic hit and the Fed stepped in with its rescue package. Even now, with the large deficits resulting from the CARES Act and President Biden's recovery package, the rate remains near 1.6 percent.

But the deficit hawks tell us this is all a temporary story. Soon the bond market vigilantes will get back on the job and send interest rates soaring. Perhaps this will happen at some point in the future, but there does not seem to be much evidence for it. The graph below shows the ratio of debt-to-GDP for most wealthy countries, compared with the interest rate on 10-year government bonds.

As can be seen, there is essentially no relationship between the two. Many countries with much larger debt-to-GDP ratios have far lower interest rates on their long-term bond. Japan takes the prize here with a debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 170 percent and an interest rate on its long-term bonds of less than 0.1 percent. However, many other countries with far higher debt-to-GDP ratios than the United States, including France, Belgium, and Greece, have much lower interest rates on their government debt.

In short, it doesn't seem like the deficit hawks have much of a case. To be clear, there is a real concern that the boost to the economy from the Biden recovery package may go to far and lead to problems with inflation. I have argued before that I think this risk is limited, and one well worth taking given the political obstacles Biden will face in getting future packages approved by Congress.

But this issue is very different from the concern that excessive debt will cause a flight from U.S. government bonds and send interest rates soaring. This one seems more a scare story designed to fool children rather than serious economic analysis.

Most of the data on the economy is looking very good these days. The number of weekly unemployment claims has fallen sharply. Levels are still high, but just over half the level we were seeing earlier this year. And, this is before all the moves by Republican governors to cut back benefits, so the decline reflects the availability of jobs, not more stringent eligibility.

Consumer spending has been rising rapidly, with the March and April levels both above where they were before the pandemic. Even restaurant sales have largely recovered. Adjusted for inflation, the April levels were just 2.7 percent below where they were in February, 2020.

"There has been some evidence that wages are increasing more rapidly in the lowest paying sectors, like hotels and restaurants. This is good news for these workers and it is not especially inflationary."

The housing market continues to be very strong, especially in lower priced areas. The increase in the Federal Housing Finance Administration's house price index from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021 was 16.0 percent in Wichita, KS, 15.8 percent in Buffalo, NY, 15.6 percent in Dayton, OH, 14.6 percent in Nashville, TN, and 13.8 percent in Gary, IN. By contrast, prices are up just 9.7 percent in the New York metro area and 6.5 percent in San Francisco.

It is too early to know if this is the start of a trend, where people take advantage of increased opportunities for remote work to live in lower cost, or whether it is a one-time blip. However, if the opportunities for increased remote work stay in place after pandemic is over, it is likely that more people will move to low-cost areas. This will both benefit those areas, by bringing in new consumers and taxpayers, and also the high cost areas, by relieving pressure on house prices.

Residential construction has also been very strong, running at close to 25 percent above the pre-pandemic pace. Starts did slow some in April, which is likely in past due to a shortage of materials, most importantly lumber. This should be alleviated in the months ahead.

Investment also is strong. New orders for capital goods are running more than 10 percent above the pre-pandemic level. This is noteworthy because it doesn't appear that the prospect of higher corporate income taxes is doing much to discourage new investment.

With the rapid growth we are now seeing across most sectors in the economy, many have raised concerns about inflation. We did see high inflation numbers in April. There are two main factors here. First, much of this is a bounce back effect, where the price of many items that plunged during the recession is now rebounding back to more normal levels. This is true in areas like hotels, airfares, and car insurance.

The other factor is that there are shortages in many areas as the economy is again getting up to steam. This is the case with lumber, where many mills shut down, anticipating a longer recession. It will take some time to get them up and running again. It is also the case with cars, where a shortage of semi-conductors, due to a fire at a plant in Japan, has hampered production. New car prices rose 0.5 percent in April, while used car prices rose an incredible 10.0 percent in the month, adding almost 0.3 percentage points to the CPI.

Both of these effects will be temporary. If we are to see sustained inflation then we really need a story where wage growth is substantially outpacing productivity growth. There is not the case at present. Wage growth has at best accelerated modestly, with the average hourly wage rising at an annual rate of 3.1 percent, comparing the last three months (February, March, April) with the prior three months (November, December, January).

This would not be the basis for real concerns with inflation, even if productivity had stayed on its pre-pandemic pace of just over 1.0 percent annually. However, productivity growth has accelerated sharply in the last year, rising 4.1 percent from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021. With GDP growth projected at close to 10 percent for the second quarter, we will almost certain add another strong quarter of productivity growth.

It is not plausible that we will sustain productivity growth of 4.0 percent, but if the pace falls back to 2.0 percent, instead of its pre-pandemic 1.0 percent rate, it is hard to see inflation becoming a problem. A 2.0 percent rate of productivity growth is consistent with 4.0 percent wage growth and 2.0 percent inflation.

There has been some evidence that wages are increasing more rapidly in the lowest paying sectors, like hotels and restaurants. This is good news for these workers and it is not especially inflationary. The average weekly earnings at the cutoff for the bottom decile is less than $500. Suppose this rises by $50. This would come to $2,500 a year. With 15 million workers in the bottom decile, that comes to less than $40 billion annually, less than 0.2 percent of GDP.

That would not be the sort of thing that is likely to set off an inflationary spiral, and we are also not likely to see wages for the bottom decile rise by 10 percent in the immediate future.

What About the Debt?

With the release of President Biden's new budget there were a slew of news stories warning about the large deficit and projected debt. The usual story about high levels of debt is that they will cause bond markets to panic and interest rates to soar.

Back in the Clinton and Obama years we were regularly regaled with stories about how the bond market vigilantes would send interest rates soaring if we didn't rein in the deficit. And of course, they would reward us with low interest rates if we were good boys and girls and got deficits down, usually by cutting spending.

It turns out that it didn't have as much to fear from higher interest rates as advertised. Ever since the Great Recession, long-term interest rates have consistently run well below the projections from the Congressional Budget Office and most other forecasters. The interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds was hovering near 2.7 percent just before the pandemic hit, in spite of the large tax cut induced deficits of the Trump years. That compares to rates that were typically well over 5.0 percent when we were running budget surpluses in the Clinton years.

Rates plunged after the pandemic hit and the Fed stepped in with its rescue package. Even now, with the large deficits resulting from the CARES Act and President Biden's recovery package, the rate remains near 1.6 percent.

But the deficit hawks tell us this is all a temporary story. Soon the bond market vigilantes will get back on the job and send interest rates soaring. Perhaps this will happen at some point in the future, but there does not seem to be much evidence for it. The graph below shows the ratio of debt-to-GDP for most wealthy countries, compared with the interest rate on 10-year government bonds.

As can be seen, there is essentially no relationship between the two. Many countries with much larger debt-to-GDP ratios have far lower interest rates on their long-term bond. Japan takes the prize here with a debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 170 percent and an interest rate on its long-term bonds of less than 0.1 percent. However, many other countries with far higher debt-to-GDP ratios than the United States, including France, Belgium, and Greece, have much lower interest rates on their government debt.

In short, it doesn't seem like the deficit hawks have much of a case. To be clear, there is a real concern that the boost to the economy from the Biden recovery package may go to far and lead to problems with inflation. I have argued before that I think this risk is limited, and one well worth taking given the political obstacles Biden will face in getting future packages approved by Congress.

But this issue is very different from the concern that excessive debt will cause a flight from U.S. government bonds and send interest rates soaring. This one seems more a scare story designed to fool children rather than serious economic analysis.