SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Built in the 1930s, the monastery has a grand presence on an otherwise nondescript street. Sunlight's tendency to tint its stucco exterior earned the monastery its nickname the "Pink Rose of the Desert." (Photo: Rose Lambert-Sluder)

In the Sonoran Desert not far from a beauty school and a car wash, stands a rose-colored castle. Sun bakes the tiered terra-cotta roofs. And the long colonnades and date palms at its front entrance evoke a dream.

On certain days of the week, a white U.S. Department of Homeland Security bus pulls up out front and 80 or so children and adults step off and disappear into a turquoise-domed sanctuary.

This former 40-bedroom Benedictine monastery in Tucson, Arizona, is where U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials have been bringing hundreds of asylum-seekers directly from detention every week since January. Casa Alitas, a Catholic nonprofit program, hosts them here for up to four days--providing meals, free clothing, toiletry kits, and medical care--preparing them for the next leg of their journeys.

At the end of their stay the asylum-seekers will board Greyhound buses bound for far-flung destinations across the U.S., where they'll stay with sponsors, usually family members, to await hearings before immigration judges.

Normally, Casa Alitas provides housing and meals from a modest four-bedroom house not far away for up to 16 people at a time. But in January, as border crossings reached an 11-year high, a wealthy developer loaned this sprawling architectural gem to Catholic Community Services of Southern Arizona for six months, rent-free. Overnight guests can number up to 300.

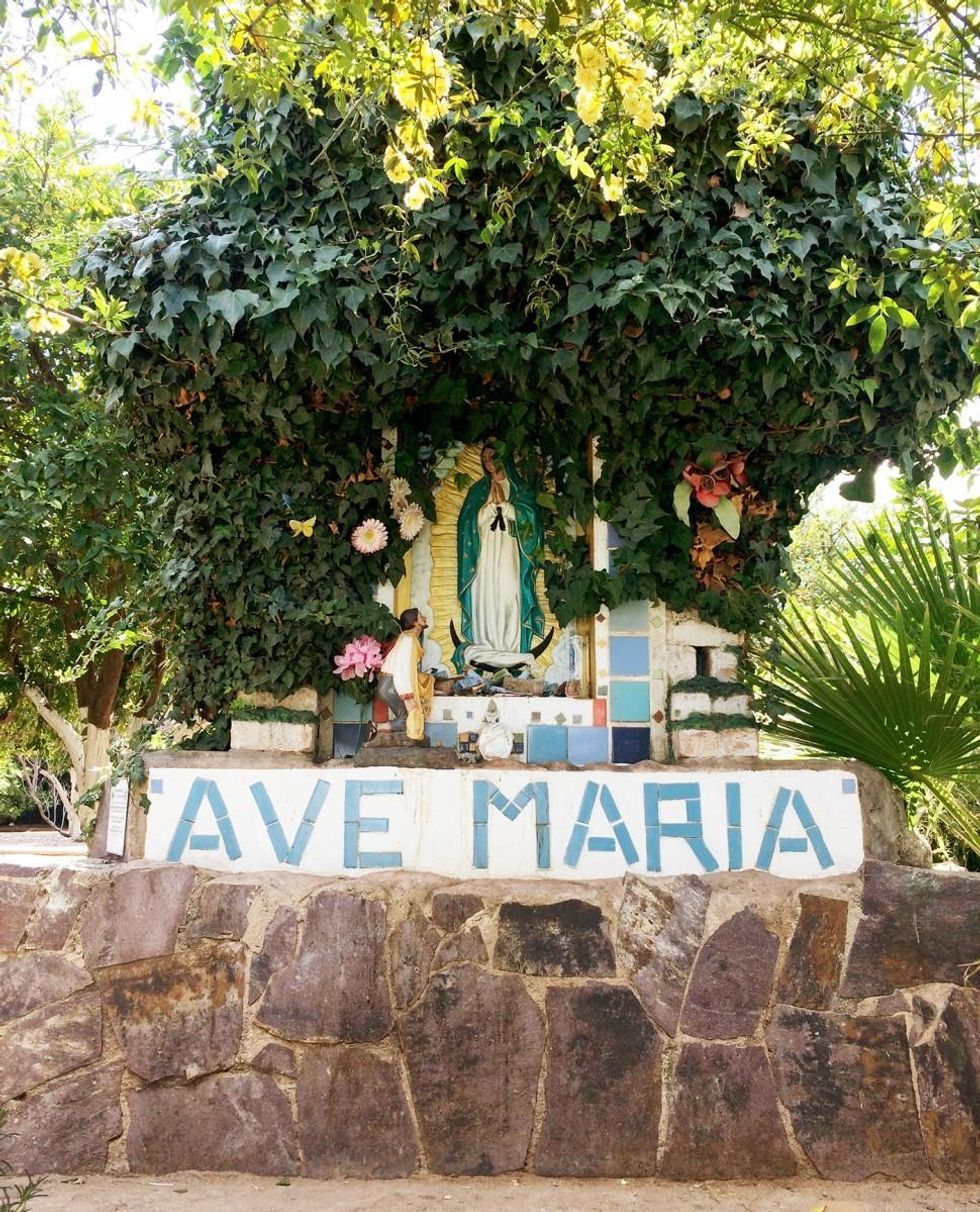

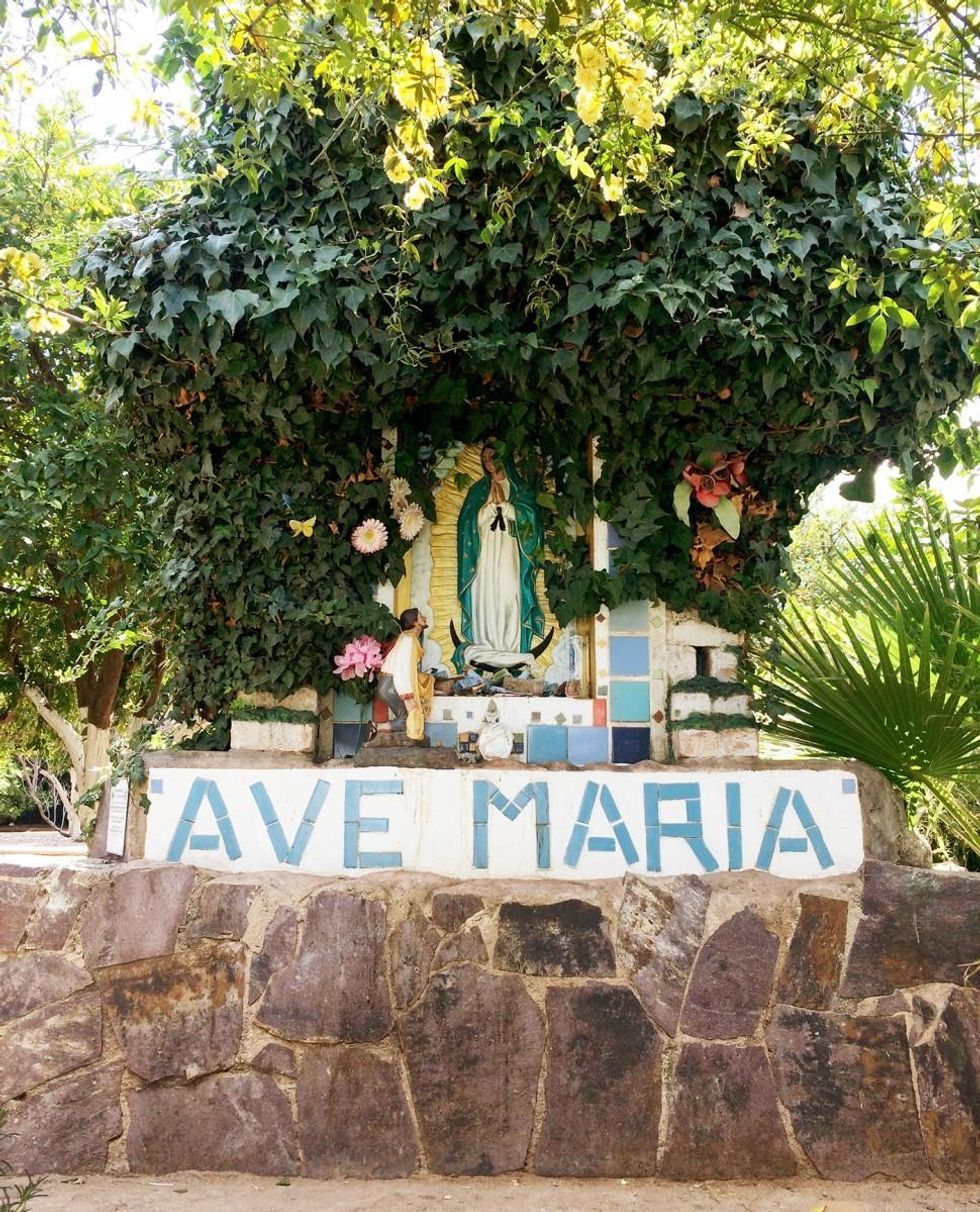

Known as the "Pink Rose of the Desert," the monastery was built in the 1930s after a group of Benedictine sisters traveled to Tucson to establish the second American branch of the Switzerland-based Perpetual Adoration Convent. They commissioned Spanish Revival architect Roy Place to design the monastery, which is marked by Baroque flourishes and a frieze with symbolic wheat, grapes, and pomegranates.

The owner, Ross Rulney, bought it two years ago from the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, whose 16 nuns spent their days here baking altar breads, singing vespers, and playing volleyball.

These days, the space hums with different energy.

Out back is a desert springtime scene, as giggling children pedal tricycles through an orchard and women sip coffee near a yellow rose bush. A soccer game is getting underway. Bras hang to dry on the courtyard orange trees, and overripe oranges tumble onto the grass. Looking around, it's easy to forget that all of this is just another scene in the country's most pressing humanitarian crisis.

On any given night, as many as 300 asylum-seekers stay here, sleeping in the nuns' former bedrooms or on cots in communal spaces such as the chapel sanctuary. Most guests are Central American and Spanish-speaking, but some speak primarily Q'eqchi', K'iche', and other Indigenous languages.

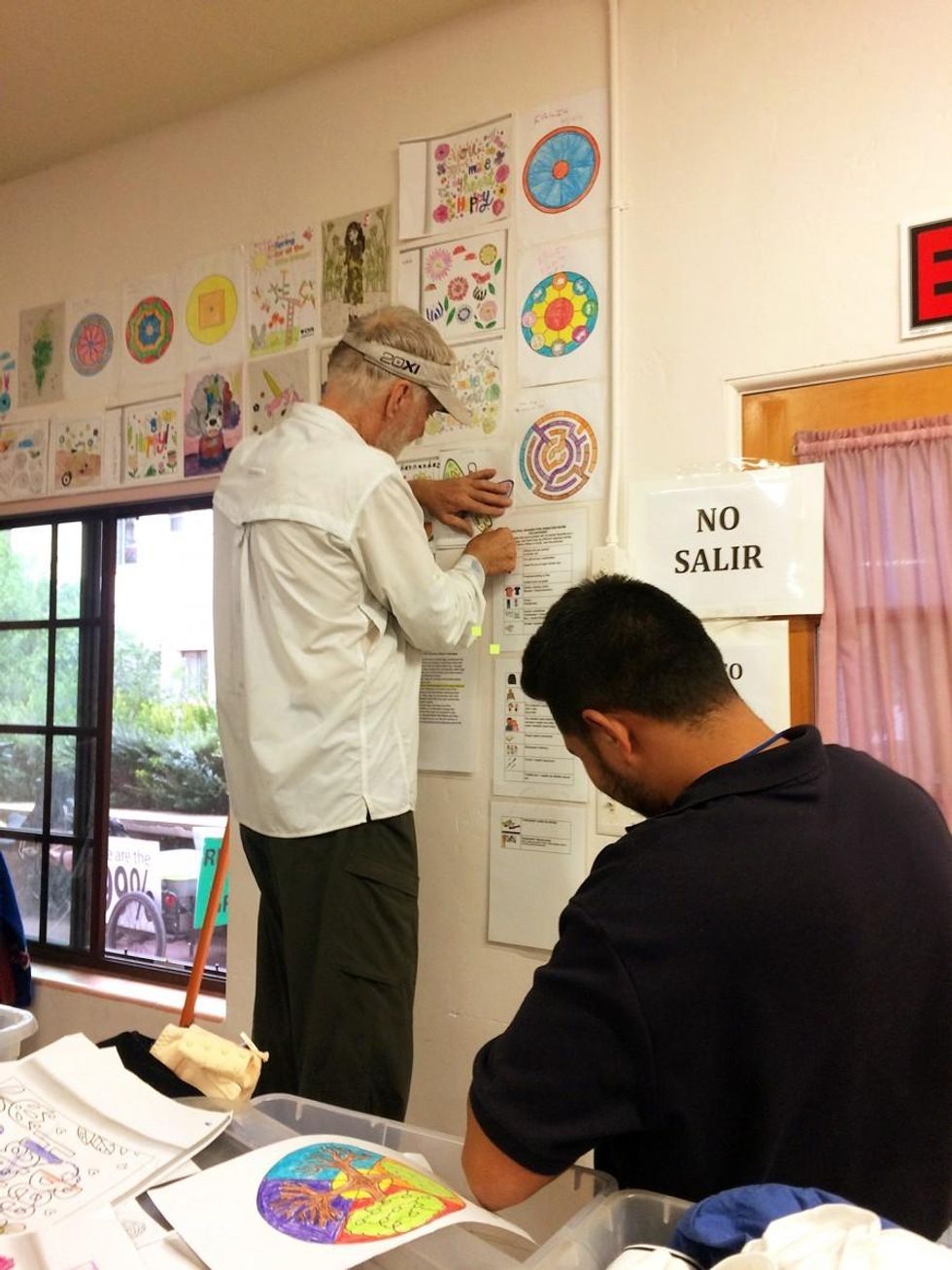

They create a revolving door at this castle, requiring about a hundred local volunteers, some working 12 hours or more a day, serving food, driving guests to the bus station, and attending to individual needs, says site coordinator Diego Pina Lopez.

Joseline, a 25-year-old who's been here just a day, gushes over a cute baby onesie with giraffe prints. She's in the clothing room of the monastery, a department set up like a well-tended thrift shop. Guests can come anytime and pick out two sets of donated clothes. Joseline's sons, Pablo and Andres, 4 and 6, both find superhero T-shirts they like.

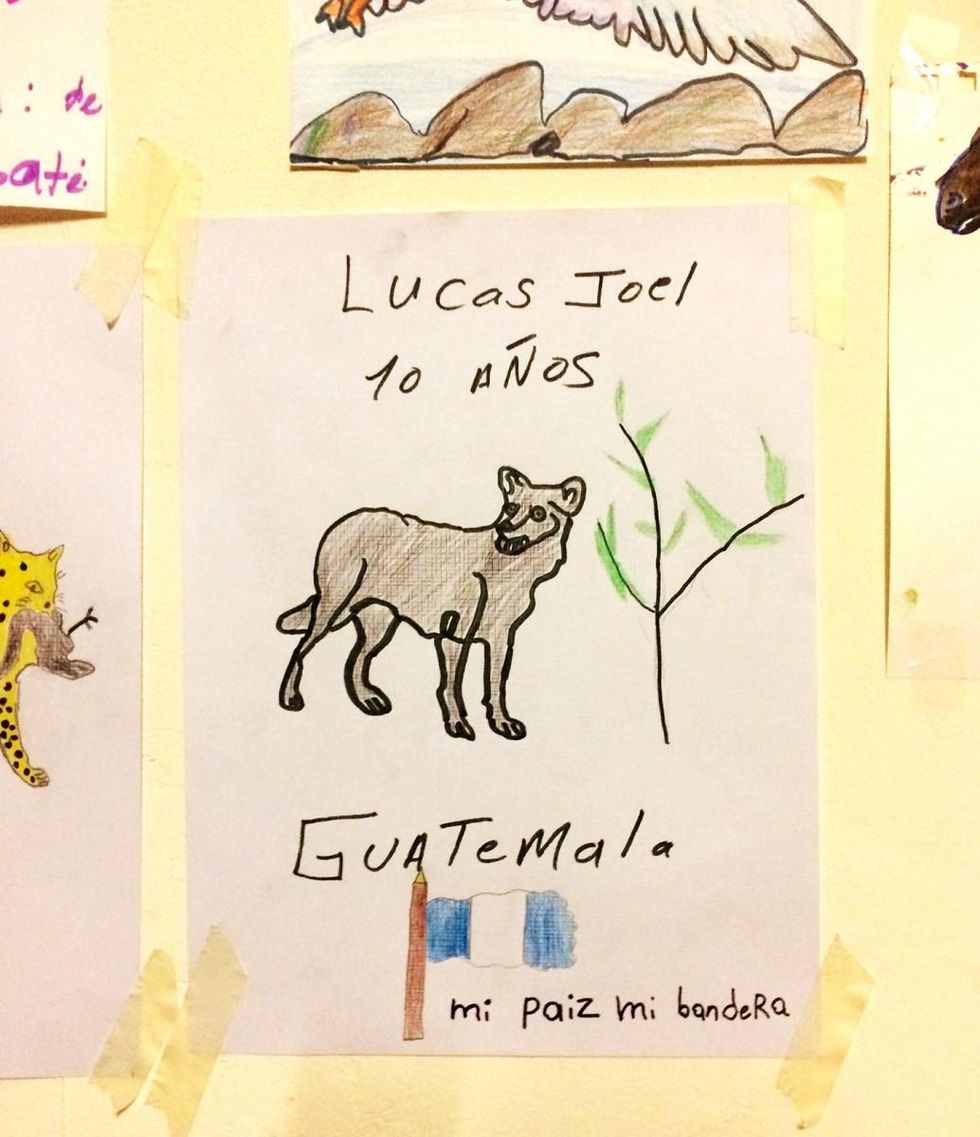

The three had left Guatemala in early March in part because Joseline felt her life threatened by her brother-in-law. She helps another woman pick out new baby clothes then quickly organizes the kids' section.

The immigration detention facility, she says, was awful. The bathrooms lacked doors, and everyone saw everything. The food was barely edible, consisting of crackers, burritos, juice cups, and ugly-tasting water, she explains. The burritos too spicy, far too spicy for her boys to eat. Breakfast might be at any hour--1 a.m., 3 a.m., 11 a.m. Guards banged on the wall.

"When we arrived [at the monastery] Sunday afternoon, we hadn't eaten since the day before," Joseline says. "We saw a doctor here, had a good dinner. The food is really nice. There are clothes, shampoo, fruit, coffee with milk, blankets."

"It's calmer here, safer. There are toys. My sons have little friends."

There is a sense of plenty. At first blush, supplies seem strained as more guests arrive. But then, new cots show up as if out of nowhere, and extra rooms open up. Soup pots run deep, and baskets of bananas are refilled as soon as they are empty.

The resources are all compliments of volunteers and other supporters of Casa Alitas. The clothes, food, personal hygiene products, coloring books, toys, baby supplies--anything a family might need--are piled, hour by hour, near the monastery's back entrance.

Email blasts ask community members for the day's most urgent needs: mini shampoos, kids' shoes, sacks and sacks of PB&Js.

A father of two, 28-year-old Gabriel sees this place as a light in the darkness. Speaking in a soft voice, he explained how he traveled from Honduras with his wife, Jessica, and daughters Hasley, 6, and Sofia, 8.

Out of gratitude, Gabriel spends full days volunteering to fold clothes and help orient newcomers, even accidentally working through lunch, then laughing at himself after realizing the late hour.

At Casa Alitas "we were met with hugs, with warmth. It was a loosening," he says, slumping his body in an exaggerated exhale to illustrate.

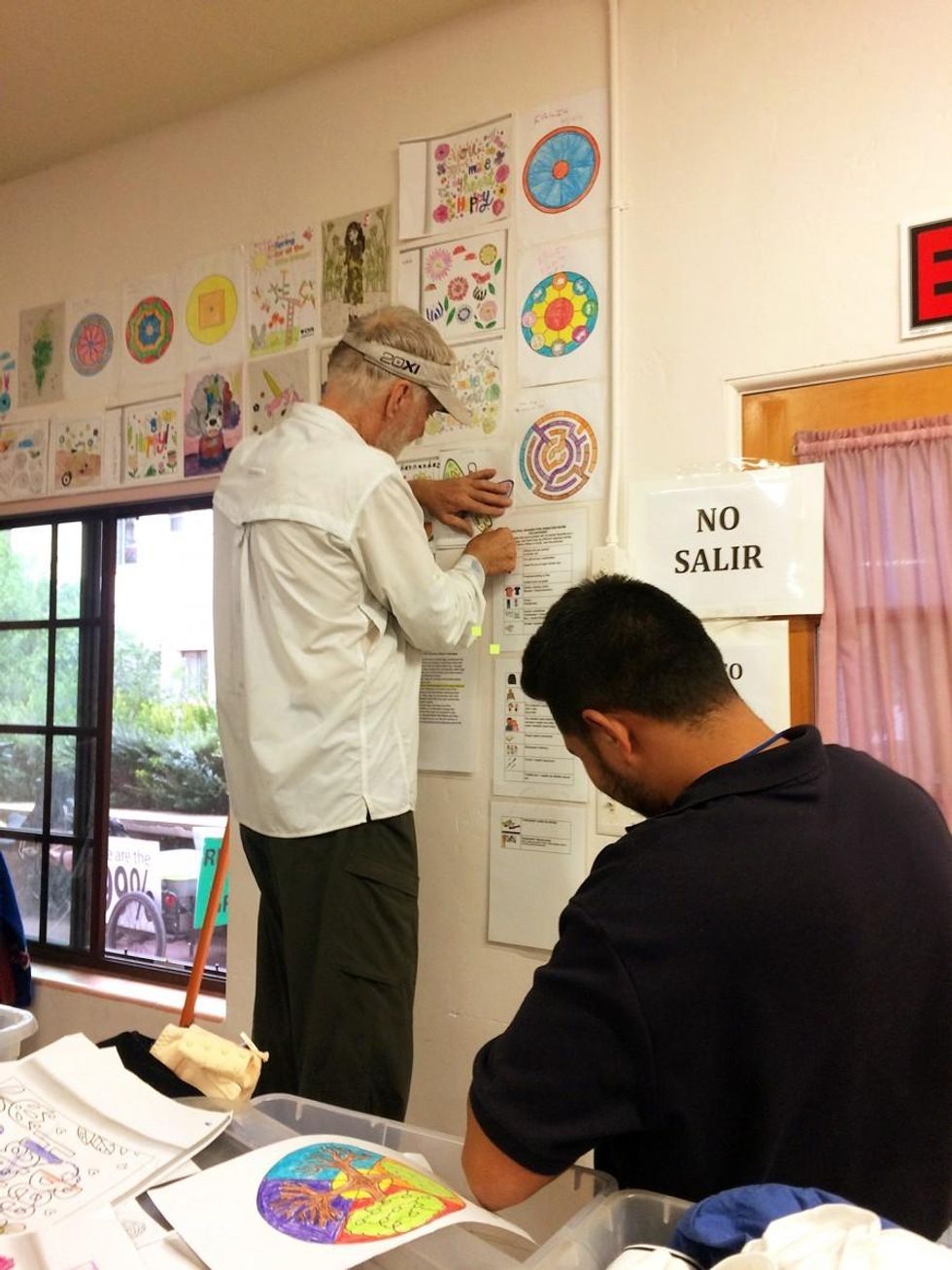

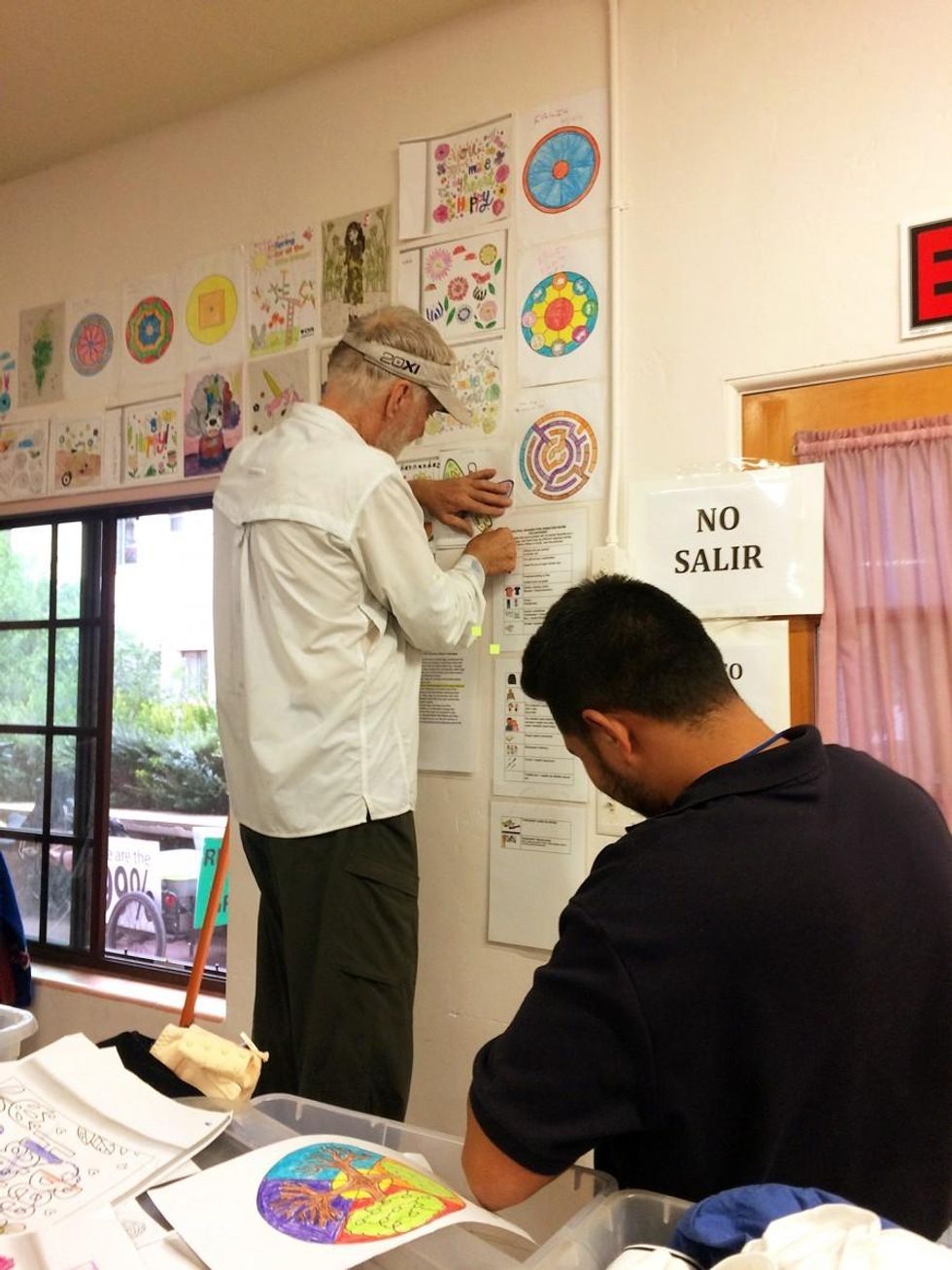

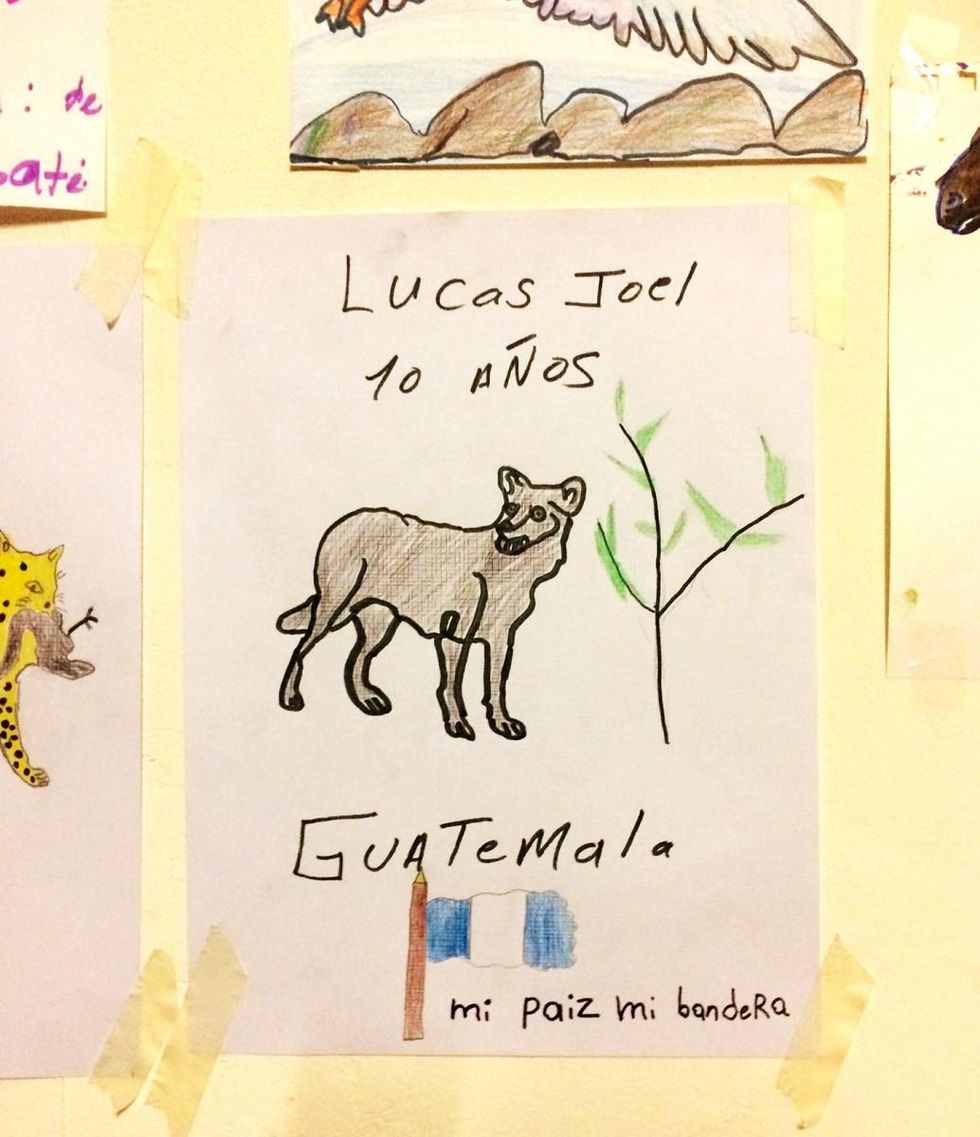

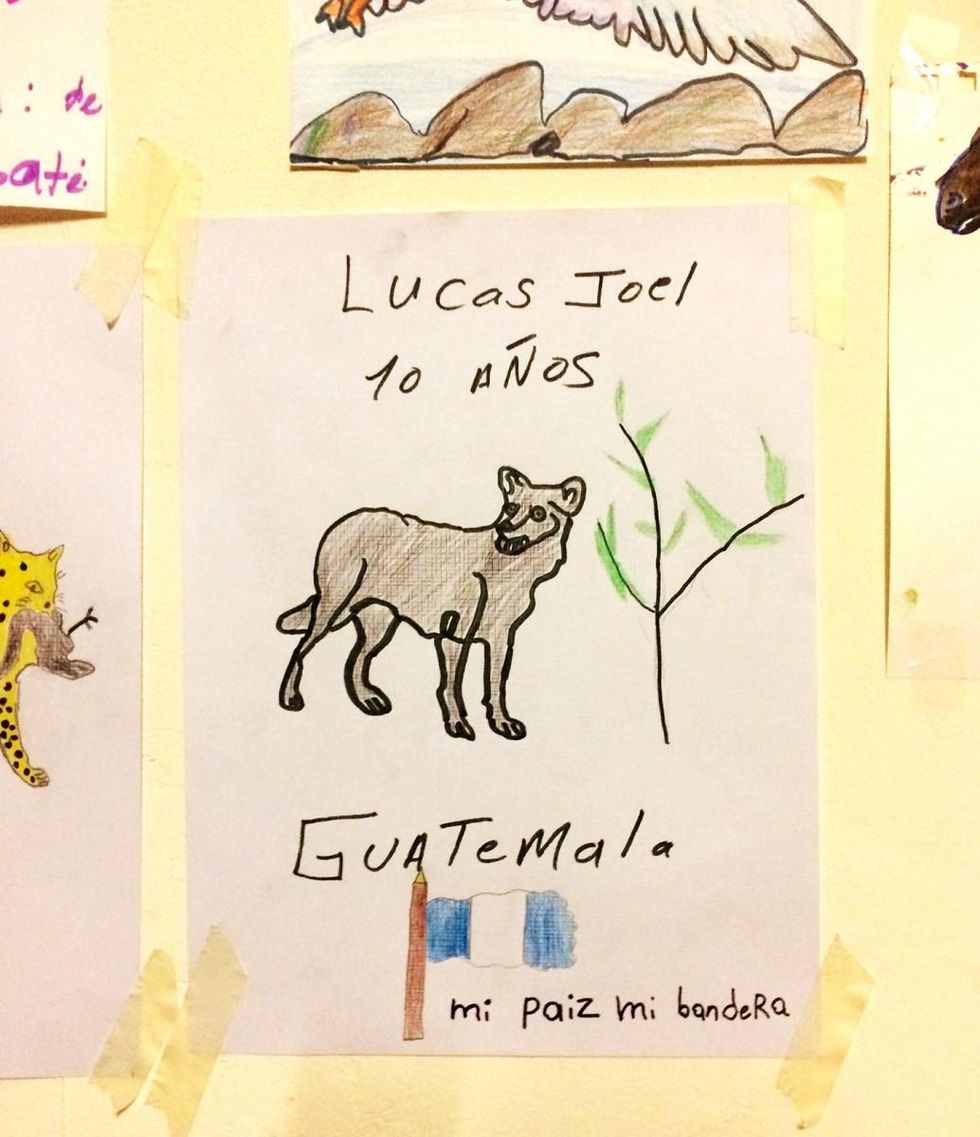

On any given day, up to 100 children, like his two, run the labyrinthine hallways, playing with donated dolls or taking volunteer-taught art classes. For them, as for their parents, the monastery is a radical shift from immigration detention and the journey that preceded it. Asked how she spends her days, his daughter Sofia, her eyes alert, says, "I play. I color." Does she help clean with her friend Aimee? She gave a sheepish smile. "No. I eat soup."

Soup is a hit here. Volunteers bring pots of homemade soup, beans, rice, and meat, which the residents eat at folding tables covered in bright vinyl cloths. A staggering 380 guests were served one Sunday evening. Managing the swell in numbers, up by about 150 the week before, meant asking volunteers to step up even more.

After dinner, a dreamy light mellows the orchard. Guests sip coffee in the courtyard, and kids turn the paths into tricycle motorways. Asked what he and Jessica will do tonight, Gabriel smiled and shrugged. "We'll relax." In two days, they leave for Baltimore, where they'll stay with family.

And in July, Casa Alitas will leave this borrowed palace and return to its four-bedroom house across town. The monastery's owner hopes to build luxury apartments on the lot's vacant land. And Casa Alitas will return to its four-bedroom house across town.

But for now, out on the lawn, as the sky grows pink, Sofia puts on sunglasses and parades around a palm tree, framed by the sunlight.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the Sonoran Desert not far from a beauty school and a car wash, stands a rose-colored castle. Sun bakes the tiered terra-cotta roofs. And the long colonnades and date palms at its front entrance evoke a dream.

On certain days of the week, a white U.S. Department of Homeland Security bus pulls up out front and 80 or so children and adults step off and disappear into a turquoise-domed sanctuary.

This former 40-bedroom Benedictine monastery in Tucson, Arizona, is where U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials have been bringing hundreds of asylum-seekers directly from detention every week since January. Casa Alitas, a Catholic nonprofit program, hosts them here for up to four days--providing meals, free clothing, toiletry kits, and medical care--preparing them for the next leg of their journeys.

At the end of their stay the asylum-seekers will board Greyhound buses bound for far-flung destinations across the U.S., where they'll stay with sponsors, usually family members, to await hearings before immigration judges.

Normally, Casa Alitas provides housing and meals from a modest four-bedroom house not far away for up to 16 people at a time. But in January, as border crossings reached an 11-year high, a wealthy developer loaned this sprawling architectural gem to Catholic Community Services of Southern Arizona for six months, rent-free. Overnight guests can number up to 300.

Known as the "Pink Rose of the Desert," the monastery was built in the 1930s after a group of Benedictine sisters traveled to Tucson to establish the second American branch of the Switzerland-based Perpetual Adoration Convent. They commissioned Spanish Revival architect Roy Place to design the monastery, which is marked by Baroque flourishes and a frieze with symbolic wheat, grapes, and pomegranates.

The owner, Ross Rulney, bought it two years ago from the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, whose 16 nuns spent their days here baking altar breads, singing vespers, and playing volleyball.

These days, the space hums with different energy.

Out back is a desert springtime scene, as giggling children pedal tricycles through an orchard and women sip coffee near a yellow rose bush. A soccer game is getting underway. Bras hang to dry on the courtyard orange trees, and overripe oranges tumble onto the grass. Looking around, it's easy to forget that all of this is just another scene in the country's most pressing humanitarian crisis.

On any given night, as many as 300 asylum-seekers stay here, sleeping in the nuns' former bedrooms or on cots in communal spaces such as the chapel sanctuary. Most guests are Central American and Spanish-speaking, but some speak primarily Q'eqchi', K'iche', and other Indigenous languages.

They create a revolving door at this castle, requiring about a hundred local volunteers, some working 12 hours or more a day, serving food, driving guests to the bus station, and attending to individual needs, says site coordinator Diego Pina Lopez.

Joseline, a 25-year-old who's been here just a day, gushes over a cute baby onesie with giraffe prints. She's in the clothing room of the monastery, a department set up like a well-tended thrift shop. Guests can come anytime and pick out two sets of donated clothes. Joseline's sons, Pablo and Andres, 4 and 6, both find superhero T-shirts they like.

The three had left Guatemala in early March in part because Joseline felt her life threatened by her brother-in-law. She helps another woman pick out new baby clothes then quickly organizes the kids' section.

The immigration detention facility, she says, was awful. The bathrooms lacked doors, and everyone saw everything. The food was barely edible, consisting of crackers, burritos, juice cups, and ugly-tasting water, she explains. The burritos too spicy, far too spicy for her boys to eat. Breakfast might be at any hour--1 a.m., 3 a.m., 11 a.m. Guards banged on the wall.

"When we arrived [at the monastery] Sunday afternoon, we hadn't eaten since the day before," Joseline says. "We saw a doctor here, had a good dinner. The food is really nice. There are clothes, shampoo, fruit, coffee with milk, blankets."

"It's calmer here, safer. There are toys. My sons have little friends."

There is a sense of plenty. At first blush, supplies seem strained as more guests arrive. But then, new cots show up as if out of nowhere, and extra rooms open up. Soup pots run deep, and baskets of bananas are refilled as soon as they are empty.

The resources are all compliments of volunteers and other supporters of Casa Alitas. The clothes, food, personal hygiene products, coloring books, toys, baby supplies--anything a family might need--are piled, hour by hour, near the monastery's back entrance.

Email blasts ask community members for the day's most urgent needs: mini shampoos, kids' shoes, sacks and sacks of PB&Js.

A father of two, 28-year-old Gabriel sees this place as a light in the darkness. Speaking in a soft voice, he explained how he traveled from Honduras with his wife, Jessica, and daughters Hasley, 6, and Sofia, 8.

Out of gratitude, Gabriel spends full days volunteering to fold clothes and help orient newcomers, even accidentally working through lunch, then laughing at himself after realizing the late hour.

At Casa Alitas "we were met with hugs, with warmth. It was a loosening," he says, slumping his body in an exaggerated exhale to illustrate.

On any given day, up to 100 children, like his two, run the labyrinthine hallways, playing with donated dolls or taking volunteer-taught art classes. For them, as for their parents, the monastery is a radical shift from immigration detention and the journey that preceded it. Asked how she spends her days, his daughter Sofia, her eyes alert, says, "I play. I color." Does she help clean with her friend Aimee? She gave a sheepish smile. "No. I eat soup."

Soup is a hit here. Volunteers bring pots of homemade soup, beans, rice, and meat, which the residents eat at folding tables covered in bright vinyl cloths. A staggering 380 guests were served one Sunday evening. Managing the swell in numbers, up by about 150 the week before, meant asking volunteers to step up even more.

After dinner, a dreamy light mellows the orchard. Guests sip coffee in the courtyard, and kids turn the paths into tricycle motorways. Asked what he and Jessica will do tonight, Gabriel smiled and shrugged. "We'll relax." In two days, they leave for Baltimore, where they'll stay with family.

And in July, Casa Alitas will leave this borrowed palace and return to its four-bedroom house across town. The monastery's owner hopes to build luxury apartments on the lot's vacant land. And Casa Alitas will return to its four-bedroom house across town.

But for now, out on the lawn, as the sky grows pink, Sofia puts on sunglasses and parades around a palm tree, framed by the sunlight.

In the Sonoran Desert not far from a beauty school and a car wash, stands a rose-colored castle. Sun bakes the tiered terra-cotta roofs. And the long colonnades and date palms at its front entrance evoke a dream.

On certain days of the week, a white U.S. Department of Homeland Security bus pulls up out front and 80 or so children and adults step off and disappear into a turquoise-domed sanctuary.

This former 40-bedroom Benedictine monastery in Tucson, Arizona, is where U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials have been bringing hundreds of asylum-seekers directly from detention every week since January. Casa Alitas, a Catholic nonprofit program, hosts them here for up to four days--providing meals, free clothing, toiletry kits, and medical care--preparing them for the next leg of their journeys.

At the end of their stay the asylum-seekers will board Greyhound buses bound for far-flung destinations across the U.S., where they'll stay with sponsors, usually family members, to await hearings before immigration judges.

Normally, Casa Alitas provides housing and meals from a modest four-bedroom house not far away for up to 16 people at a time. But in January, as border crossings reached an 11-year high, a wealthy developer loaned this sprawling architectural gem to Catholic Community Services of Southern Arizona for six months, rent-free. Overnight guests can number up to 300.

Known as the "Pink Rose of the Desert," the monastery was built in the 1930s after a group of Benedictine sisters traveled to Tucson to establish the second American branch of the Switzerland-based Perpetual Adoration Convent. They commissioned Spanish Revival architect Roy Place to design the monastery, which is marked by Baroque flourishes and a frieze with symbolic wheat, grapes, and pomegranates.

The owner, Ross Rulney, bought it two years ago from the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, whose 16 nuns spent their days here baking altar breads, singing vespers, and playing volleyball.

These days, the space hums with different energy.

Out back is a desert springtime scene, as giggling children pedal tricycles through an orchard and women sip coffee near a yellow rose bush. A soccer game is getting underway. Bras hang to dry on the courtyard orange trees, and overripe oranges tumble onto the grass. Looking around, it's easy to forget that all of this is just another scene in the country's most pressing humanitarian crisis.

On any given night, as many as 300 asylum-seekers stay here, sleeping in the nuns' former bedrooms or on cots in communal spaces such as the chapel sanctuary. Most guests are Central American and Spanish-speaking, but some speak primarily Q'eqchi', K'iche', and other Indigenous languages.

They create a revolving door at this castle, requiring about a hundred local volunteers, some working 12 hours or more a day, serving food, driving guests to the bus station, and attending to individual needs, says site coordinator Diego Pina Lopez.

Joseline, a 25-year-old who's been here just a day, gushes over a cute baby onesie with giraffe prints. She's in the clothing room of the monastery, a department set up like a well-tended thrift shop. Guests can come anytime and pick out two sets of donated clothes. Joseline's sons, Pablo and Andres, 4 and 6, both find superhero T-shirts they like.

The three had left Guatemala in early March in part because Joseline felt her life threatened by her brother-in-law. She helps another woman pick out new baby clothes then quickly organizes the kids' section.

The immigration detention facility, she says, was awful. The bathrooms lacked doors, and everyone saw everything. The food was barely edible, consisting of crackers, burritos, juice cups, and ugly-tasting water, she explains. The burritos too spicy, far too spicy for her boys to eat. Breakfast might be at any hour--1 a.m., 3 a.m., 11 a.m. Guards banged on the wall.

"When we arrived [at the monastery] Sunday afternoon, we hadn't eaten since the day before," Joseline says. "We saw a doctor here, had a good dinner. The food is really nice. There are clothes, shampoo, fruit, coffee with milk, blankets."

"It's calmer here, safer. There are toys. My sons have little friends."

There is a sense of plenty. At first blush, supplies seem strained as more guests arrive. But then, new cots show up as if out of nowhere, and extra rooms open up. Soup pots run deep, and baskets of bananas are refilled as soon as they are empty.

The resources are all compliments of volunteers and other supporters of Casa Alitas. The clothes, food, personal hygiene products, coloring books, toys, baby supplies--anything a family might need--are piled, hour by hour, near the monastery's back entrance.

Email blasts ask community members for the day's most urgent needs: mini shampoos, kids' shoes, sacks and sacks of PB&Js.

A father of two, 28-year-old Gabriel sees this place as a light in the darkness. Speaking in a soft voice, he explained how he traveled from Honduras with his wife, Jessica, and daughters Hasley, 6, and Sofia, 8.

Out of gratitude, Gabriel spends full days volunteering to fold clothes and help orient newcomers, even accidentally working through lunch, then laughing at himself after realizing the late hour.

At Casa Alitas "we were met with hugs, with warmth. It was a loosening," he says, slumping his body in an exaggerated exhale to illustrate.

On any given day, up to 100 children, like his two, run the labyrinthine hallways, playing with donated dolls or taking volunteer-taught art classes. For them, as for their parents, the monastery is a radical shift from immigration detention and the journey that preceded it. Asked how she spends her days, his daughter Sofia, her eyes alert, says, "I play. I color." Does she help clean with her friend Aimee? She gave a sheepish smile. "No. I eat soup."

Soup is a hit here. Volunteers bring pots of homemade soup, beans, rice, and meat, which the residents eat at folding tables covered in bright vinyl cloths. A staggering 380 guests were served one Sunday evening. Managing the swell in numbers, up by about 150 the week before, meant asking volunteers to step up even more.

After dinner, a dreamy light mellows the orchard. Guests sip coffee in the courtyard, and kids turn the paths into tricycle motorways. Asked what he and Jessica will do tonight, Gabriel smiled and shrugged. "We'll relax." In two days, they leave for Baltimore, where they'll stay with family.

And in July, Casa Alitas will leave this borrowed palace and return to its four-bedroom house across town. The monastery's owner hopes to build luxury apartments on the lot's vacant land. And Casa Alitas will return to its four-bedroom house across town.

But for now, out on the lawn, as the sky grows pink, Sofia puts on sunglasses and parades around a palm tree, framed by the sunlight.