SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"It has amassed such power that experts and public opinion refer to it as the digital public square: the place where people protest, sign up for public events, get information about politics, and more." (Photo: Legal Loop)

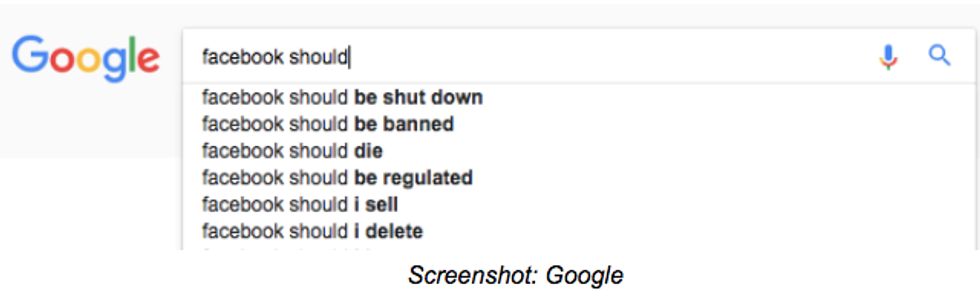

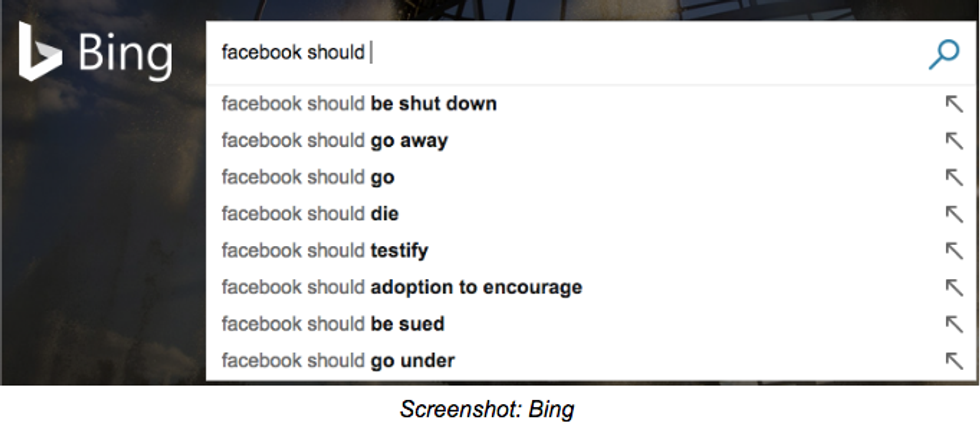

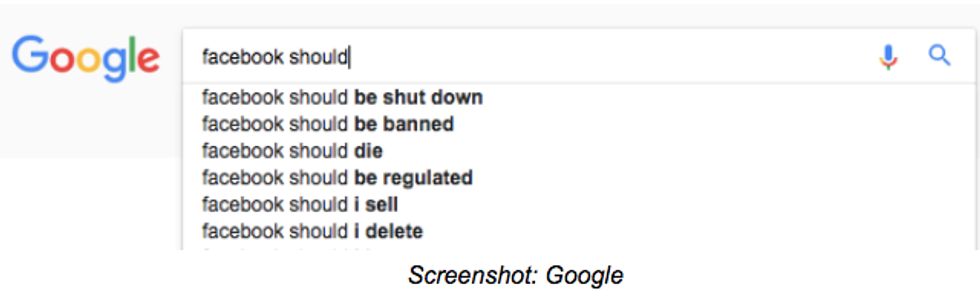

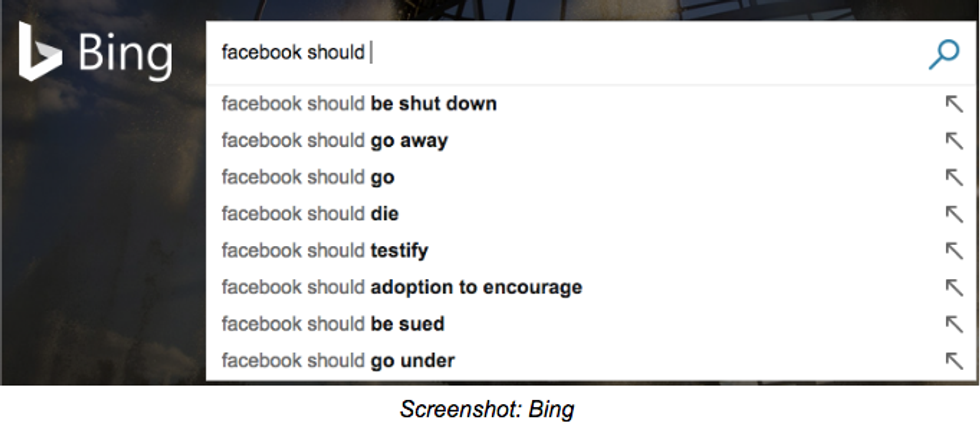

Every policy-tweak Facebook attempts to roll out is faced with public criticism. This signals a structural problem: Facebook developed quicker than its own systems of governance and now struggles to carry its own weight. In other words, Facebook seems to lack the legitimacy to exercise the huge power it has amassed over the years.

If the user base were smaller, Facebook would have a group of like-minded individuals that could be more easily catered to. But Facebook has become very big and diverse. With over 2 billion active monthly users, it's bigger and more diverse than any community we've ever seen.

If Facebook hadn't taken such an aggressive strategy towards consolidating itself as a central node for information distribution, then it would be held to lower standards. But it has amassed such power that experts and public opinion refer to it as the digital public square: the place where people protest, sign up for public events, get information about politics, and more.

So Facebook's responsibilities go beyond those of any other digital platform, and yet people seem to believe it fails to cope with these responsibilities. The percentage of people who think Facebook is having a negative impact on society is as high as 33% in Australia and 20% in Brazil. This happens against a background in which many are pointing out Facebook's business practices in the global south represent a new form of colonialism.

Creating rules to govern a group that is large, diverse, and has a lot of skin in the game is a problem that is not in itself new. It's actually a problem rulers have faced daily since before the times of the Roman Empire.

How have they survived? Institution building. Centuries of iterations towards developing institutions capable of offering solutions that are fair. Or perhaps, more accurately, perceived as fair. If a person feels a decision has been unfair, there is a system of checks and balances: an Ombuds that oversees the acts of government and is ready to act in defense of people's interests, a system of independent judges, and, ultimately, an electoral system through which to change the people in charge of appointing the heads of institutions.

As part of its efforts to stamp out misinformation, Facebook is building a network of fact checking NGOs. This decision might seem like an approach towards institution building. But the process is opaque and based on a customer-service model that excludes the chance of real engagement.

Facebook needs to engage its users in more substantive acts of participation. That is how a shared identity can be developed, a feeling of belonging. The precursors to an actual community. Wikipedia offers a good example of a participatory governance model with proven capacity to deal with tussle. Facebook has a larger community to cater to, but also has more funds. Facebook can and should go further.

Institutions are ultimately built on community and trust. Facebook has some sort of loose community it can start working with. But is definitely running low on trust.

Facebook mistakenly assumes that locally respected fact-checking NGOs can supply the trust Facebook itself is lacking. But NGOs lack standing to execute the tasks Facebook wants to offload.

In a liberal democracy, NGOs can legitimately elevate arguments and offer counterarguments to government positions. These actions imply adding or organizing the arguments of a public debate. In liberal democracies we assume arguments will be tested publicly, and after the positions of different stakeholders have been taken into account, perhaps adopted as policy by democratically elected representatives. NGOs have not gone through any process that could possibly provide the legitimacy to limit the arguments available for public debate.

If Facebook wants to remain the digital public square, it needs to develop its own process of institution building. Bottom-up. One that resolves the tension between maximizing corporate profit and being responsive to social problems. It needs to limit Facebook Corp. to selling ads, and delegate decision-making power regarding all other matters onto a set of institutions, including enforcing transparency rules over Facebook Corp. Facebook needs to involve its +2 billion members in debate, elections and decision-making. Candidates in charge of explaining to the users how the technology works, and discuss publicly how it should be used. Candidates in charge of translating human rights to this digital age. Their impact would go far beyond Facebook itself. It would reduce a gap in information that is fuelling a teclash and is likely to lead governments to implement bad regulation that would affect the whole internet.

The NGO-network approach is a reasonable patch to an urgent problem. But Facebook needs to start signalling what its long-term strategy looks like. Many, including myself, believe the power Facebook (and a handful of other companies) yield is becoming too big of a risk for society at large. Calls for Facebook to be broken up are gaining traction as public trust in the corporation gets increasingly eroded. Facebook can mitigate part of these concerns by distributing political control over the platform.

So Facebook should....build institutions. Yet there are reasons to be cynical about Facebook's ability to establish institutions that actually work. After all Facebook has shareholders to satisfy on a quarterly basis. But even shareholders should understand that Facebook's long term sustainability requires a new governance structure. One that can ease the growing tensions between human values and profit. One that, by putting people first, ensures users feel part of some imagined community that is worth belonging to. One that is prepared for the challenges the future has in stall.

Mark Zuckerberg has a chance to take his promise to build community seriously. And it could be a community of a size and complexity the world has never seen.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Every policy-tweak Facebook attempts to roll out is faced with public criticism. This signals a structural problem: Facebook developed quicker than its own systems of governance and now struggles to carry its own weight. In other words, Facebook seems to lack the legitimacy to exercise the huge power it has amassed over the years.

If the user base were smaller, Facebook would have a group of like-minded individuals that could be more easily catered to. But Facebook has become very big and diverse. With over 2 billion active monthly users, it's bigger and more diverse than any community we've ever seen.

If Facebook hadn't taken such an aggressive strategy towards consolidating itself as a central node for information distribution, then it would be held to lower standards. But it has amassed such power that experts and public opinion refer to it as the digital public square: the place where people protest, sign up for public events, get information about politics, and more.

So Facebook's responsibilities go beyond those of any other digital platform, and yet people seem to believe it fails to cope with these responsibilities. The percentage of people who think Facebook is having a negative impact on society is as high as 33% in Australia and 20% in Brazil. This happens against a background in which many are pointing out Facebook's business practices in the global south represent a new form of colonialism.

Creating rules to govern a group that is large, diverse, and has a lot of skin in the game is a problem that is not in itself new. It's actually a problem rulers have faced daily since before the times of the Roman Empire.

How have they survived? Institution building. Centuries of iterations towards developing institutions capable of offering solutions that are fair. Or perhaps, more accurately, perceived as fair. If a person feels a decision has been unfair, there is a system of checks and balances: an Ombuds that oversees the acts of government and is ready to act in defense of people's interests, a system of independent judges, and, ultimately, an electoral system through which to change the people in charge of appointing the heads of institutions.

As part of its efforts to stamp out misinformation, Facebook is building a network of fact checking NGOs. This decision might seem like an approach towards institution building. But the process is opaque and based on a customer-service model that excludes the chance of real engagement.

Facebook needs to engage its users in more substantive acts of participation. That is how a shared identity can be developed, a feeling of belonging. The precursors to an actual community. Wikipedia offers a good example of a participatory governance model with proven capacity to deal with tussle. Facebook has a larger community to cater to, but also has more funds. Facebook can and should go further.

Institutions are ultimately built on community and trust. Facebook has some sort of loose community it can start working with. But is definitely running low on trust.

Facebook mistakenly assumes that locally respected fact-checking NGOs can supply the trust Facebook itself is lacking. But NGOs lack standing to execute the tasks Facebook wants to offload.

In a liberal democracy, NGOs can legitimately elevate arguments and offer counterarguments to government positions. These actions imply adding or organizing the arguments of a public debate. In liberal democracies we assume arguments will be tested publicly, and after the positions of different stakeholders have been taken into account, perhaps adopted as policy by democratically elected representatives. NGOs have not gone through any process that could possibly provide the legitimacy to limit the arguments available for public debate.

If Facebook wants to remain the digital public square, it needs to develop its own process of institution building. Bottom-up. One that resolves the tension between maximizing corporate profit and being responsive to social problems. It needs to limit Facebook Corp. to selling ads, and delegate decision-making power regarding all other matters onto a set of institutions, including enforcing transparency rules over Facebook Corp. Facebook needs to involve its +2 billion members in debate, elections and decision-making. Candidates in charge of explaining to the users how the technology works, and discuss publicly how it should be used. Candidates in charge of translating human rights to this digital age. Their impact would go far beyond Facebook itself. It would reduce a gap in information that is fuelling a teclash and is likely to lead governments to implement bad regulation that would affect the whole internet.

The NGO-network approach is a reasonable patch to an urgent problem. But Facebook needs to start signalling what its long-term strategy looks like. Many, including myself, believe the power Facebook (and a handful of other companies) yield is becoming too big of a risk for society at large. Calls for Facebook to be broken up are gaining traction as public trust in the corporation gets increasingly eroded. Facebook can mitigate part of these concerns by distributing political control over the platform.

So Facebook should....build institutions. Yet there are reasons to be cynical about Facebook's ability to establish institutions that actually work. After all Facebook has shareholders to satisfy on a quarterly basis. But even shareholders should understand that Facebook's long term sustainability requires a new governance structure. One that can ease the growing tensions between human values and profit. One that, by putting people first, ensures users feel part of some imagined community that is worth belonging to. One that is prepared for the challenges the future has in stall.

Mark Zuckerberg has a chance to take his promise to build community seriously. And it could be a community of a size and complexity the world has never seen.

Every policy-tweak Facebook attempts to roll out is faced with public criticism. This signals a structural problem: Facebook developed quicker than its own systems of governance and now struggles to carry its own weight. In other words, Facebook seems to lack the legitimacy to exercise the huge power it has amassed over the years.

If the user base were smaller, Facebook would have a group of like-minded individuals that could be more easily catered to. But Facebook has become very big and diverse. With over 2 billion active monthly users, it's bigger and more diverse than any community we've ever seen.

If Facebook hadn't taken such an aggressive strategy towards consolidating itself as a central node for information distribution, then it would be held to lower standards. But it has amassed such power that experts and public opinion refer to it as the digital public square: the place where people protest, sign up for public events, get information about politics, and more.

So Facebook's responsibilities go beyond those of any other digital platform, and yet people seem to believe it fails to cope with these responsibilities. The percentage of people who think Facebook is having a negative impact on society is as high as 33% in Australia and 20% in Brazil. This happens against a background in which many are pointing out Facebook's business practices in the global south represent a new form of colonialism.

Creating rules to govern a group that is large, diverse, and has a lot of skin in the game is a problem that is not in itself new. It's actually a problem rulers have faced daily since before the times of the Roman Empire.

How have they survived? Institution building. Centuries of iterations towards developing institutions capable of offering solutions that are fair. Or perhaps, more accurately, perceived as fair. If a person feels a decision has been unfair, there is a system of checks and balances: an Ombuds that oversees the acts of government and is ready to act in defense of people's interests, a system of independent judges, and, ultimately, an electoral system through which to change the people in charge of appointing the heads of institutions.

As part of its efforts to stamp out misinformation, Facebook is building a network of fact checking NGOs. This decision might seem like an approach towards institution building. But the process is opaque and based on a customer-service model that excludes the chance of real engagement.

Facebook needs to engage its users in more substantive acts of participation. That is how a shared identity can be developed, a feeling of belonging. The precursors to an actual community. Wikipedia offers a good example of a participatory governance model with proven capacity to deal with tussle. Facebook has a larger community to cater to, but also has more funds. Facebook can and should go further.

Institutions are ultimately built on community and trust. Facebook has some sort of loose community it can start working with. But is definitely running low on trust.

Facebook mistakenly assumes that locally respected fact-checking NGOs can supply the trust Facebook itself is lacking. But NGOs lack standing to execute the tasks Facebook wants to offload.

In a liberal democracy, NGOs can legitimately elevate arguments and offer counterarguments to government positions. These actions imply adding or organizing the arguments of a public debate. In liberal democracies we assume arguments will be tested publicly, and after the positions of different stakeholders have been taken into account, perhaps adopted as policy by democratically elected representatives. NGOs have not gone through any process that could possibly provide the legitimacy to limit the arguments available for public debate.

If Facebook wants to remain the digital public square, it needs to develop its own process of institution building. Bottom-up. One that resolves the tension between maximizing corporate profit and being responsive to social problems. It needs to limit Facebook Corp. to selling ads, and delegate decision-making power regarding all other matters onto a set of institutions, including enforcing transparency rules over Facebook Corp. Facebook needs to involve its +2 billion members in debate, elections and decision-making. Candidates in charge of explaining to the users how the technology works, and discuss publicly how it should be used. Candidates in charge of translating human rights to this digital age. Their impact would go far beyond Facebook itself. It would reduce a gap in information that is fuelling a teclash and is likely to lead governments to implement bad regulation that would affect the whole internet.

The NGO-network approach is a reasonable patch to an urgent problem. But Facebook needs to start signalling what its long-term strategy looks like. Many, including myself, believe the power Facebook (and a handful of other companies) yield is becoming too big of a risk for society at large. Calls for Facebook to be broken up are gaining traction as public trust in the corporation gets increasingly eroded. Facebook can mitigate part of these concerns by distributing political control over the platform.

So Facebook should....build institutions. Yet there are reasons to be cynical about Facebook's ability to establish institutions that actually work. After all Facebook has shareholders to satisfy on a quarterly basis. But even shareholders should understand that Facebook's long term sustainability requires a new governance structure. One that can ease the growing tensions between human values and profit. One that, by putting people first, ensures users feel part of some imagined community that is worth belonging to. One that is prepared for the challenges the future has in stall.

Mark Zuckerberg has a chance to take his promise to build community seriously. And it could be a community of a size and complexity the world has never seen.