How Greece's Creditors Trounced Syriza

When Syriza’s leadership failed to seriously plan for a Eurozone exit, they let Europe’s central bank turn the screws.

As the final votes poured in last January, Greece seemed primed for a political earthquake.

Syriza, the nascent left-wing coalition led by the telegenic Alexis Tsipras, rocketed to power in a decisive vote against the devastating neoliberal economic policies foisted on Greece by its international creditors and implemented by Tspiras' predescessors.

Syriza's victory produced a collective sigh of relief. The old political dynasties of PASOK and New Democracy, Greece's ruling parties that had racked up enormous debt over 40 years of entrenched corruption and economic mismanagement on a grand scale, had finally fallen. Syntagma Square, the nerve center of anti-austerity protests since 2010, now opened up for celebrations.

Yet come mid-summer, Tspiras himself was ramming through a new bundle of pension cuts, sales tax hikes, labor regulation rollbacks, and privatization schemes every bit as austere as the ones he'd run against. Greece's European creditors had given him no choice, he lamented, but to begrudgingly implement a slate of measures "I don't believe in."

Tsipras may have accepted the role begrudgingly, but he played it convincingly. He effectively transformed Syriza into a pro-austerity party, purging dissenting ministers from his cabinet as the party's left flank bolted the bloc. Having lost his parliamentary majority, he then announced new elections to bolster his hold on power, launching a campaign urging the Greek people to vote for Syriza as a pro-memorandum party free from the insitutionalized corruption of previous governments. The move elicited anger, widespread disappointment, and disillusionment. Twenty-nine Syriza legislators abandoned the party to form the rival Popular Unity party.

Greeks will go to the polls again on September 20, with the country as mired as ever in economic and political turmoil. How did it come to this?

It's worth recalling what it was that Syriza once ran against.

The hope invested in the party came after five long years in which New Democracy and PASOK effectively defaulted on the people, shifting the responsibility for 240 billion euros in debt by private investors and banks onto the public.

The loans the old ruling parties requested from Greece's "troika" of creditors -- the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission -- to pay that debt came at a steep political and economic cost: Unelected technocrats in the EU's headquarters in Brussels drew up some 143 memoranda laws, with thousands of attached articles, which were enacted by legislative decree or rammed through parliament under suffocating, creditor-imposed timetables.

The combination of deep wage and pension cuts, sweeping public sector lay-offs, and regressive taxes -- alongside the decimation of the country's public health and education budgets -- shrank the Greek economy by 25 percent, pushing it from a recession into a full blown depression. It triggered the largest drop in living standards since the end of World War II.

By 2013, over 44 percent of the Greek population had an income below the poverty line. National unemployment rocketed from around 7 percent in May 2008 to over 25 percent in February 2015. Youth unemployment rose even higher, hitting 50 percent last February even after tens of thousands of young people emigrated.

Since 2010, public sector wages have been slashed by nearly half, private sector employment has collapsed, and pensions have been cut by 44 percent. Whole extended families are being supported by one grandparent's 400-euro monthly pension, or one worker's monthly minimum wage of 520 euros. Child poverty has nearly doubled to 40 percent -- the highest rate in the developed world.

Small businesses and the self-employed were also hit hard. "Business is bad and I am barely hanging on," says 47-year-old Yiannis Skarakis, who runs a digital products and services business. "Taxes have increased significantly with the austerity measures. I always pay what I can, but if it's a choice between paying taxes and feeding my children, I choose to put food on the table."

On the other hand, the austerity program is working very well for the creditors, who have a huge profit incentive in maintaining the debt status quo.

According to the Jubilee debt relief campaign's latest analysis, "the European Central Bank and its member national central banks are on track to make between EUR10 billion and EUR22 billion of profit out of lending to Greece, if Greece pays its debts in full."

"The European Central Bank has acted exactly like a vulture fund," adds Jubilee economist Tim Jones, "buying up debts cheaply during the crisis, refusing to take part in a necessary restructuring of the debt, and demanding to be repaid at a large profit."

War

Almost immediately after taking power, Syriza plunged into an asymmetrical war with Greece's creditors and their neoliberal economic model. The loan terms, party leaders said, had to be renegotiated in light of Syriza's democratic mandate to ease austerity within the Eurozone.

But the creditors were indifferent to Syriza's political arguments. And besides, the European Central Bank had a trump card: cash flow.

Greece has been unable to borrow from the markets since 2009, and without loan financing since August 2014. On February 4, shortly after Syriza took power, the European Central Bank stopped accepting Greek bonds as collateral, replacing its normal funding operations with a drip-feed of weekly approved emergency liquidity assistance. It also capped Greece's treasury bills at 9 billion euros, down from the normal 16 billion, and excluded Greece from the trillion-euro quantitative easing program for southern European countries.

The result was a full-blown liquidity crisis. The Greek government had to scramble to fund its daily operations even as it tried to renegotiate the devastating terms of previous bailouts.

Increasingly desperate to avoid default as the negotiations dragged on, the government started draining public coffers, including national health insurance and pension funds, to pay public sector salaries and service debt. In an extraordinary move, the prime minister issued a legislative decree in April to municipal governments and public entities, including hospitals and schools, to transfer their cash reserves to the Central Bank of Greece.

This was not popular, and the consequences were severe.

"The public hospitals are in dire crisis," explains Dimitris Sildiris, who owns a restaurant south of Athens. "My 83-year-old mother was recently admitted to Agios Pavlos hospital in Thessaloniki for kidney dialysis. They don't have basic supplies like medicines, bandages, bed linen, even toilet paper, and the patients' relatives have to fill the gap. Hospitals are even boiling hypodermic needles for re-use. This is explicitly forbidden and doesn't happen anywhere, not even in Africa! The fact that Syriza drew on hospital cash reserves to pay the debt is unforgivable."

Referendum

Tsipras went into office vowing to break the austerity chokehold Greece's creditors had placed the country in. But he also needed cash, and the troika insisted that Athens could only receive fresh loans if it committed to the austerity program.

Looking to break the stalemate, Tsipras announced a referendum for July 5, calling on voters to reject the creditors' proposal for further austerity measures in exchange for loan financing to Athens.

What followed can only be described as blatant political interference by European politicians and bureaucrats. They immediately framed the referendum as a vote on Greece's Eurozone membership, openly campaigning for both a Yes vote and the overthrow of the Syriza government.

But they didn't just campaign. When the referendum was announced, the European Central Bank tightened liquidity to the Greek banking system yet again, prompting the government to impose capital controls to prevent a months-long bank jog from becoming a bank run.

ATM cash withdrawals were limited to 60 euros per day. Retirees -- many of whom had become sole breadwinners for their families -- had to queue outside Bank of Greece branches on July 1 to withdraw just 120 euros of their monthly pension, without knowing when the remainder would be available.

Meanwhile, Greece's oligarch-owned corporate media aggressively spun a false narrative of a panicked public and widespread social unrest. Discredited former prime ministers went on TV to advocate a Yes vote as stations ran file footage presenting Turkish victims of the 1999 earthquake and account holders in the 2012 Cyprus banking crisis as distressed Greek pensioners.

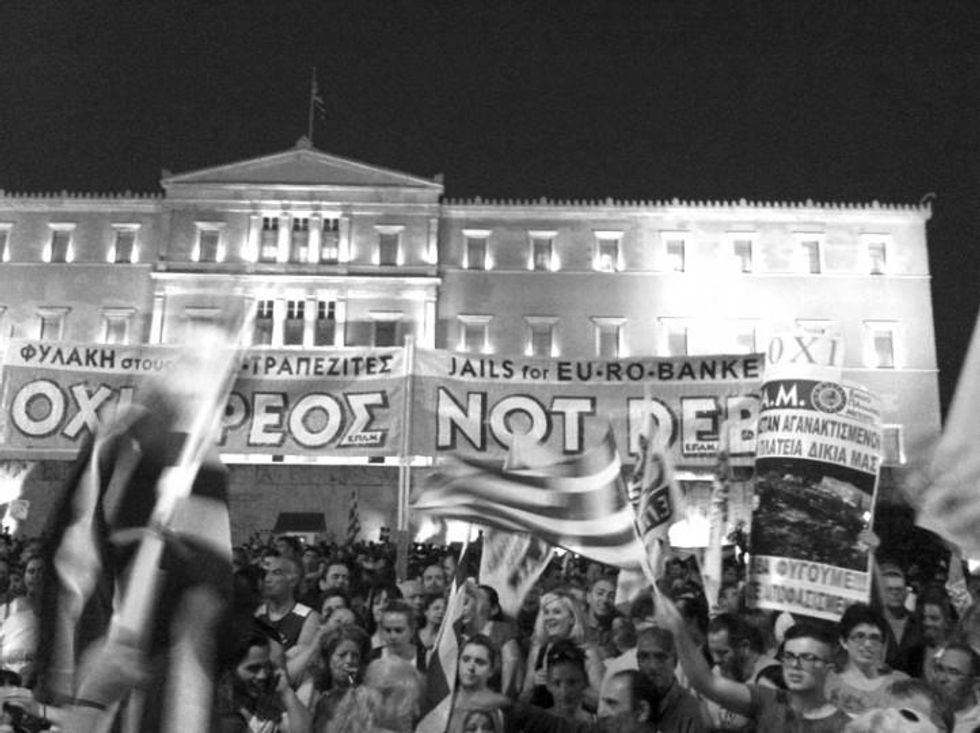

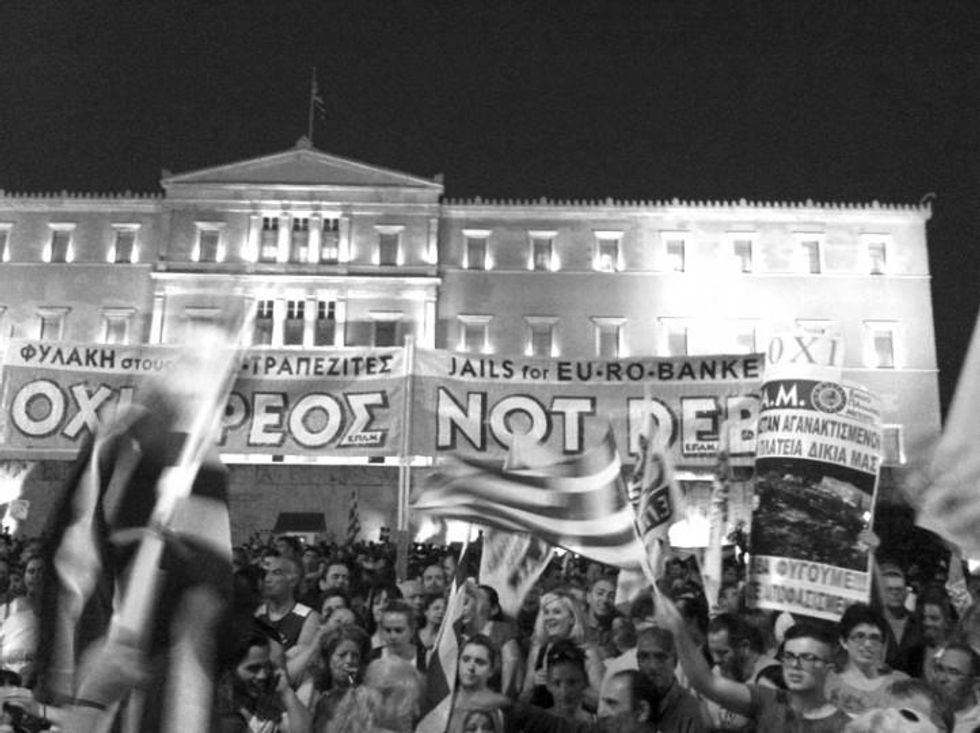

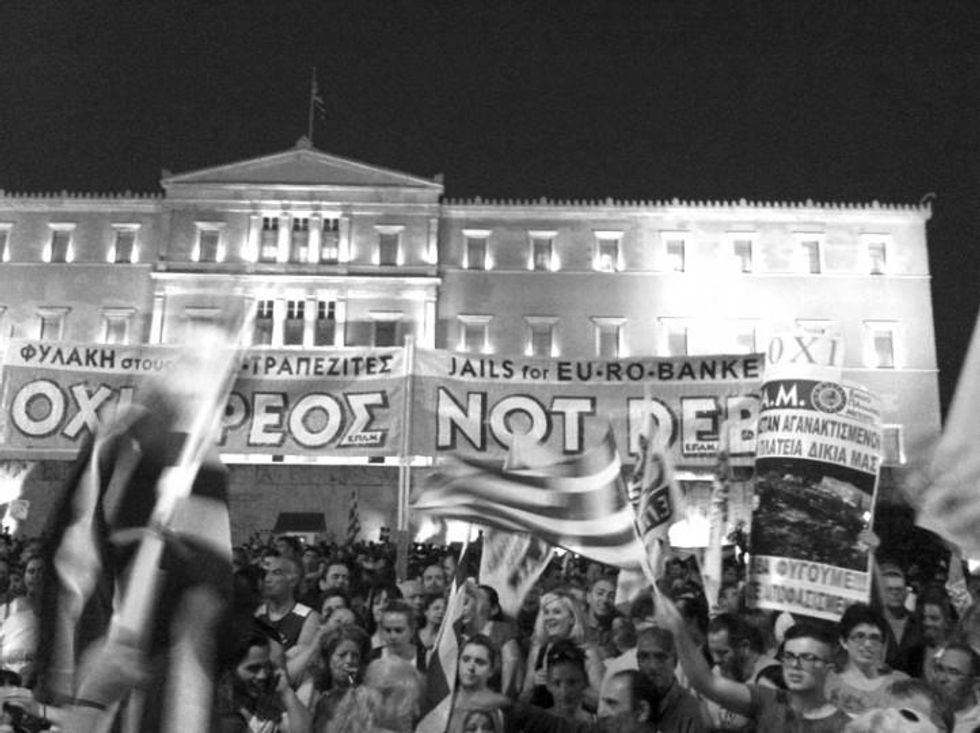

Yet the resistance to austerity persisted. A June 29 rally for a No vote proved particularly extraordinary, not only for the sheer numbers and diversity of the crowd -- from toddlers to grandparents -- but because exactly four years earlier, over 100,000 people had gathered in the same spot to protest the first troika austerity measures. The second No rally held on July 3 was even bigger. At both rallies, the atmosphere in the jam-packed crowd was electric. Greeks had overcome fear. A new mood of defiance, empowerment, and celebration prevailed.

The result? An emphatic victory for the No side, with over 61 percent of Greeks voting to support their government's stance against the creditors.

Defeat

It was a triumphant moment, but it wasn't to last.

Tsipras took the referendum result to the Eurozone summit on Saturday, July 11 to strengthen Greece's hand in the negotiations, even as the ECB threatened to cut its lifeline to Greek banks without an agreement by Sunday night.

After a gruelling weekend of talks, Tsipras was presented with an ultimatum: Greece would either remain an indebted ward of Germany, the dominant Eurozone country, or face a disorderly exit from the Eurozone and the total collapse of the Greek banking system. After 17 hours of all-night talks, Tsipras signed the "agreement" shortly after dawn on Monday, albeit with a proverbial gun to his head.

Thus Greece ceded its sovereignty to its creditors, who now hold legislative and executive power in Greece. Germany now essentially controls Greece's finances and its banks -- and even has the power to veto Greek laws, since draft laws must be submitted for approval to creditors.

The business of the Greek parliament was reduced to rubber-stamping hundreds of new austerity laws that will gouge 12 billion euros from the depressed economy. It was these laws that Tsipras was charged with ushering through Athens, alienating and purging many of his own MPs and Central Commitee members in the process.

One particularly egregious set of provisions in the new memorandum marks 50 billion euros of Greek state assets -- from regional airports servicing busy tourist destinations (already snapped up by the German government firm Frapport) to utility companies and islands -- for transfer to a privatization fund under creditor control. An added clause prevents their future re-purchase, depriving Greece of strategic income-producing national assets.

It was an unambiguous defeat. They "crucified Tsipras in there" a Eurozone official attending the summit told the Financial Times.

Resilience

In Greece, reactions have been mixed. Many view Tsipras' capitulation as unavoidable under the circumstances, and they respect Syriza for fighting in Greece's corner until the bitter end.

Others say the ultimatum didn't occur in a vacuum. Both Tsipras and then-Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, critics counter, accepted most of the austerity measures at the start of negotiations, focusing instead on easing the rest while keeping Greece in the Eurozone. Crucially, they never questioned the legitimacy of the debt itself, despite the findings of the Preliminary Report of the Truth Committee on Public Debt, which concluded that the majority of Greek debt is illegal, odious, and unsustainable. And, they say, the Syriza leaders improvised their way through months of negotiations, draining the public coffers to service the debt while refusing to seriously prepare for a Eurozone exit should Germany's position prove intractable -- as it has been for five years. That effectively deprived Greece of its only real leverage in the negotiations, and left Greece at the mercy of the European Central Bank.

These critics see Tsipras more like Judas the betrayer than Christ the crucified. They lament that the Euro Summit "agreement" is far more extreme than the program Greek voters rejected on July 5. And they ask why Tsipras called a referendum if he wasn't prepared to honor the result.

"What does Tsipras think he's doing?" asks 29-year-old Ourania Tzavara, a bartender from Athens. "We voted no!"

"We do not have the right to turn the people's no into a yes," added former parliament speaker and Syriza MP Zoe Konstantopoulou, who will stand as an independent on September 20. "We have a duty to honor their verdict."

Exhausted by an 8-month-old government that brought a new memorandum instead of a new anti-austerity era -- and weary of frequent elections and governments that don't represent them -- a quarter of Greek voters polled in late August were undecided. By mid-September, Syriza and New Democracy -- the latter revived with a new leader from the old guard -- are both polling at around 27 percent. Some say they won't be voting, because regardless of who's in power, the outcome seems to be the same.

Yet Greeks remain determined to stop their free-fall into poverty, halt the mass exodus of their youth, and reclaim their future. "It's a huge blow but we have to re-group and keep going," says Irini Katsou, who co-owns the Athens restaurant with Sildiris. "Just because Tsipras surrendered doesn't mean that we have to."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As the final votes poured in last January, Greece seemed primed for a political earthquake.

Syriza, the nascent left-wing coalition led by the telegenic Alexis Tsipras, rocketed to power in a decisive vote against the devastating neoliberal economic policies foisted on Greece by its international creditors and implemented by Tspiras' predescessors.

Syriza's victory produced a collective sigh of relief. The old political dynasties of PASOK and New Democracy, Greece's ruling parties that had racked up enormous debt over 40 years of entrenched corruption and economic mismanagement on a grand scale, had finally fallen. Syntagma Square, the nerve center of anti-austerity protests since 2010, now opened up for celebrations.

Yet come mid-summer, Tspiras himself was ramming through a new bundle of pension cuts, sales tax hikes, labor regulation rollbacks, and privatization schemes every bit as austere as the ones he'd run against. Greece's European creditors had given him no choice, he lamented, but to begrudgingly implement a slate of measures "I don't believe in."

Tsipras may have accepted the role begrudgingly, but he played it convincingly. He effectively transformed Syriza into a pro-austerity party, purging dissenting ministers from his cabinet as the party's left flank bolted the bloc. Having lost his parliamentary majority, he then announced new elections to bolster his hold on power, launching a campaign urging the Greek people to vote for Syriza as a pro-memorandum party free from the insitutionalized corruption of previous governments. The move elicited anger, widespread disappointment, and disillusionment. Twenty-nine Syriza legislators abandoned the party to form the rival Popular Unity party.

Greeks will go to the polls again on September 20, with the country as mired as ever in economic and political turmoil. How did it come to this?

It's worth recalling what it was that Syriza once ran against.

The hope invested in the party came after five long years in which New Democracy and PASOK effectively defaulted on the people, shifting the responsibility for 240 billion euros in debt by private investors and banks onto the public.

The loans the old ruling parties requested from Greece's "troika" of creditors -- the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission -- to pay that debt came at a steep political and economic cost: Unelected technocrats in the EU's headquarters in Brussels drew up some 143 memoranda laws, with thousands of attached articles, which were enacted by legislative decree or rammed through parliament under suffocating, creditor-imposed timetables.

The combination of deep wage and pension cuts, sweeping public sector lay-offs, and regressive taxes -- alongside the decimation of the country's public health and education budgets -- shrank the Greek economy by 25 percent, pushing it from a recession into a full blown depression. It triggered the largest drop in living standards since the end of World War II.

By 2013, over 44 percent of the Greek population had an income below the poverty line. National unemployment rocketed from around 7 percent in May 2008 to over 25 percent in February 2015. Youth unemployment rose even higher, hitting 50 percent last February even after tens of thousands of young people emigrated.

Since 2010, public sector wages have been slashed by nearly half, private sector employment has collapsed, and pensions have been cut by 44 percent. Whole extended families are being supported by one grandparent's 400-euro monthly pension, or one worker's monthly minimum wage of 520 euros. Child poverty has nearly doubled to 40 percent -- the highest rate in the developed world.

Small businesses and the self-employed were also hit hard. "Business is bad and I am barely hanging on," says 47-year-old Yiannis Skarakis, who runs a digital products and services business. "Taxes have increased significantly with the austerity measures. I always pay what I can, but if it's a choice between paying taxes and feeding my children, I choose to put food on the table."

On the other hand, the austerity program is working very well for the creditors, who have a huge profit incentive in maintaining the debt status quo.

According to the Jubilee debt relief campaign's latest analysis, "the European Central Bank and its member national central banks are on track to make between EUR10 billion and EUR22 billion of profit out of lending to Greece, if Greece pays its debts in full."

"The European Central Bank has acted exactly like a vulture fund," adds Jubilee economist Tim Jones, "buying up debts cheaply during the crisis, refusing to take part in a necessary restructuring of the debt, and demanding to be repaid at a large profit."

War

Almost immediately after taking power, Syriza plunged into an asymmetrical war with Greece's creditors and their neoliberal economic model. The loan terms, party leaders said, had to be renegotiated in light of Syriza's democratic mandate to ease austerity within the Eurozone.

But the creditors were indifferent to Syriza's political arguments. And besides, the European Central Bank had a trump card: cash flow.

Greece has been unable to borrow from the markets since 2009, and without loan financing since August 2014. On February 4, shortly after Syriza took power, the European Central Bank stopped accepting Greek bonds as collateral, replacing its normal funding operations with a drip-feed of weekly approved emergency liquidity assistance. It also capped Greece's treasury bills at 9 billion euros, down from the normal 16 billion, and excluded Greece from the trillion-euro quantitative easing program for southern European countries.

The result was a full-blown liquidity crisis. The Greek government had to scramble to fund its daily operations even as it tried to renegotiate the devastating terms of previous bailouts.

Increasingly desperate to avoid default as the negotiations dragged on, the government started draining public coffers, including national health insurance and pension funds, to pay public sector salaries and service debt. In an extraordinary move, the prime minister issued a legislative decree in April to municipal governments and public entities, including hospitals and schools, to transfer their cash reserves to the Central Bank of Greece.

This was not popular, and the consequences were severe.

"The public hospitals are in dire crisis," explains Dimitris Sildiris, who owns a restaurant south of Athens. "My 83-year-old mother was recently admitted to Agios Pavlos hospital in Thessaloniki for kidney dialysis. They don't have basic supplies like medicines, bandages, bed linen, even toilet paper, and the patients' relatives have to fill the gap. Hospitals are even boiling hypodermic needles for re-use. This is explicitly forbidden and doesn't happen anywhere, not even in Africa! The fact that Syriza drew on hospital cash reserves to pay the debt is unforgivable."

Referendum

Tsipras went into office vowing to break the austerity chokehold Greece's creditors had placed the country in. But he also needed cash, and the troika insisted that Athens could only receive fresh loans if it committed to the austerity program.

Looking to break the stalemate, Tsipras announced a referendum for July 5, calling on voters to reject the creditors' proposal for further austerity measures in exchange for loan financing to Athens.

What followed can only be described as blatant political interference by European politicians and bureaucrats. They immediately framed the referendum as a vote on Greece's Eurozone membership, openly campaigning for both a Yes vote and the overthrow of the Syriza government.

But they didn't just campaign. When the referendum was announced, the European Central Bank tightened liquidity to the Greek banking system yet again, prompting the government to impose capital controls to prevent a months-long bank jog from becoming a bank run.

ATM cash withdrawals were limited to 60 euros per day. Retirees -- many of whom had become sole breadwinners for their families -- had to queue outside Bank of Greece branches on July 1 to withdraw just 120 euros of their monthly pension, without knowing when the remainder would be available.

Meanwhile, Greece's oligarch-owned corporate media aggressively spun a false narrative of a panicked public and widespread social unrest. Discredited former prime ministers went on TV to advocate a Yes vote as stations ran file footage presenting Turkish victims of the 1999 earthquake and account holders in the 2012 Cyprus banking crisis as distressed Greek pensioners.

Yet the resistance to austerity persisted. A June 29 rally for a No vote proved particularly extraordinary, not only for the sheer numbers and diversity of the crowd -- from toddlers to grandparents -- but because exactly four years earlier, over 100,000 people had gathered in the same spot to protest the first troika austerity measures. The second No rally held on July 3 was even bigger. At both rallies, the atmosphere in the jam-packed crowd was electric. Greeks had overcome fear. A new mood of defiance, empowerment, and celebration prevailed.

The result? An emphatic victory for the No side, with over 61 percent of Greeks voting to support their government's stance against the creditors.

Defeat

It was a triumphant moment, but it wasn't to last.

Tsipras took the referendum result to the Eurozone summit on Saturday, July 11 to strengthen Greece's hand in the negotiations, even as the ECB threatened to cut its lifeline to Greek banks without an agreement by Sunday night.

After a gruelling weekend of talks, Tsipras was presented with an ultimatum: Greece would either remain an indebted ward of Germany, the dominant Eurozone country, or face a disorderly exit from the Eurozone and the total collapse of the Greek banking system. After 17 hours of all-night talks, Tsipras signed the "agreement" shortly after dawn on Monday, albeit with a proverbial gun to his head.

Thus Greece ceded its sovereignty to its creditors, who now hold legislative and executive power in Greece. Germany now essentially controls Greece's finances and its banks -- and even has the power to veto Greek laws, since draft laws must be submitted for approval to creditors.

The business of the Greek parliament was reduced to rubber-stamping hundreds of new austerity laws that will gouge 12 billion euros from the depressed economy. It was these laws that Tsipras was charged with ushering through Athens, alienating and purging many of his own MPs and Central Commitee members in the process.

One particularly egregious set of provisions in the new memorandum marks 50 billion euros of Greek state assets -- from regional airports servicing busy tourist destinations (already snapped up by the German government firm Frapport) to utility companies and islands -- for transfer to a privatization fund under creditor control. An added clause prevents their future re-purchase, depriving Greece of strategic income-producing national assets.

It was an unambiguous defeat. They "crucified Tsipras in there" a Eurozone official attending the summit told the Financial Times.

Resilience

In Greece, reactions have been mixed. Many view Tsipras' capitulation as unavoidable under the circumstances, and they respect Syriza for fighting in Greece's corner until the bitter end.

Others say the ultimatum didn't occur in a vacuum. Both Tsipras and then-Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, critics counter, accepted most of the austerity measures at the start of negotiations, focusing instead on easing the rest while keeping Greece in the Eurozone. Crucially, they never questioned the legitimacy of the debt itself, despite the findings of the Preliminary Report of the Truth Committee on Public Debt, which concluded that the majority of Greek debt is illegal, odious, and unsustainable. And, they say, the Syriza leaders improvised their way through months of negotiations, draining the public coffers to service the debt while refusing to seriously prepare for a Eurozone exit should Germany's position prove intractable -- as it has been for five years. That effectively deprived Greece of its only real leverage in the negotiations, and left Greece at the mercy of the European Central Bank.

These critics see Tsipras more like Judas the betrayer than Christ the crucified. They lament that the Euro Summit "agreement" is far more extreme than the program Greek voters rejected on July 5. And they ask why Tsipras called a referendum if he wasn't prepared to honor the result.

"What does Tsipras think he's doing?" asks 29-year-old Ourania Tzavara, a bartender from Athens. "We voted no!"

"We do not have the right to turn the people's no into a yes," added former parliament speaker and Syriza MP Zoe Konstantopoulou, who will stand as an independent on September 20. "We have a duty to honor their verdict."

Exhausted by an 8-month-old government that brought a new memorandum instead of a new anti-austerity era -- and weary of frequent elections and governments that don't represent them -- a quarter of Greek voters polled in late August were undecided. By mid-September, Syriza and New Democracy -- the latter revived with a new leader from the old guard -- are both polling at around 27 percent. Some say they won't be voting, because regardless of who's in power, the outcome seems to be the same.

Yet Greeks remain determined to stop their free-fall into poverty, halt the mass exodus of their youth, and reclaim their future. "It's a huge blow but we have to re-group and keep going," says Irini Katsou, who co-owns the Athens restaurant with Sildiris. "Just because Tsipras surrendered doesn't mean that we have to."

As the final votes poured in last January, Greece seemed primed for a political earthquake.

Syriza, the nascent left-wing coalition led by the telegenic Alexis Tsipras, rocketed to power in a decisive vote against the devastating neoliberal economic policies foisted on Greece by its international creditors and implemented by Tspiras' predescessors.

Syriza's victory produced a collective sigh of relief. The old political dynasties of PASOK and New Democracy, Greece's ruling parties that had racked up enormous debt over 40 years of entrenched corruption and economic mismanagement on a grand scale, had finally fallen. Syntagma Square, the nerve center of anti-austerity protests since 2010, now opened up for celebrations.

Yet come mid-summer, Tspiras himself was ramming through a new bundle of pension cuts, sales tax hikes, labor regulation rollbacks, and privatization schemes every bit as austere as the ones he'd run against. Greece's European creditors had given him no choice, he lamented, but to begrudgingly implement a slate of measures "I don't believe in."

Tsipras may have accepted the role begrudgingly, but he played it convincingly. He effectively transformed Syriza into a pro-austerity party, purging dissenting ministers from his cabinet as the party's left flank bolted the bloc. Having lost his parliamentary majority, he then announced new elections to bolster his hold on power, launching a campaign urging the Greek people to vote for Syriza as a pro-memorandum party free from the insitutionalized corruption of previous governments. The move elicited anger, widespread disappointment, and disillusionment. Twenty-nine Syriza legislators abandoned the party to form the rival Popular Unity party.

Greeks will go to the polls again on September 20, with the country as mired as ever in economic and political turmoil. How did it come to this?

It's worth recalling what it was that Syriza once ran against.

The hope invested in the party came after five long years in which New Democracy and PASOK effectively defaulted on the people, shifting the responsibility for 240 billion euros in debt by private investors and banks onto the public.

The loans the old ruling parties requested from Greece's "troika" of creditors -- the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission -- to pay that debt came at a steep political and economic cost: Unelected technocrats in the EU's headquarters in Brussels drew up some 143 memoranda laws, with thousands of attached articles, which were enacted by legislative decree or rammed through parliament under suffocating, creditor-imposed timetables.

The combination of deep wage and pension cuts, sweeping public sector lay-offs, and regressive taxes -- alongside the decimation of the country's public health and education budgets -- shrank the Greek economy by 25 percent, pushing it from a recession into a full blown depression. It triggered the largest drop in living standards since the end of World War II.

By 2013, over 44 percent of the Greek population had an income below the poverty line. National unemployment rocketed from around 7 percent in May 2008 to over 25 percent in February 2015. Youth unemployment rose even higher, hitting 50 percent last February even after tens of thousands of young people emigrated.

Since 2010, public sector wages have been slashed by nearly half, private sector employment has collapsed, and pensions have been cut by 44 percent. Whole extended families are being supported by one grandparent's 400-euro monthly pension, or one worker's monthly minimum wage of 520 euros. Child poverty has nearly doubled to 40 percent -- the highest rate in the developed world.

Small businesses and the self-employed were also hit hard. "Business is bad and I am barely hanging on," says 47-year-old Yiannis Skarakis, who runs a digital products and services business. "Taxes have increased significantly with the austerity measures. I always pay what I can, but if it's a choice between paying taxes and feeding my children, I choose to put food on the table."

On the other hand, the austerity program is working very well for the creditors, who have a huge profit incentive in maintaining the debt status quo.

According to the Jubilee debt relief campaign's latest analysis, "the European Central Bank and its member national central banks are on track to make between EUR10 billion and EUR22 billion of profit out of lending to Greece, if Greece pays its debts in full."

"The European Central Bank has acted exactly like a vulture fund," adds Jubilee economist Tim Jones, "buying up debts cheaply during the crisis, refusing to take part in a necessary restructuring of the debt, and demanding to be repaid at a large profit."

War

Almost immediately after taking power, Syriza plunged into an asymmetrical war with Greece's creditors and their neoliberal economic model. The loan terms, party leaders said, had to be renegotiated in light of Syriza's democratic mandate to ease austerity within the Eurozone.

But the creditors were indifferent to Syriza's political arguments. And besides, the European Central Bank had a trump card: cash flow.

Greece has been unable to borrow from the markets since 2009, and without loan financing since August 2014. On February 4, shortly after Syriza took power, the European Central Bank stopped accepting Greek bonds as collateral, replacing its normal funding operations with a drip-feed of weekly approved emergency liquidity assistance. It also capped Greece's treasury bills at 9 billion euros, down from the normal 16 billion, and excluded Greece from the trillion-euro quantitative easing program for southern European countries.

The result was a full-blown liquidity crisis. The Greek government had to scramble to fund its daily operations even as it tried to renegotiate the devastating terms of previous bailouts.

Increasingly desperate to avoid default as the negotiations dragged on, the government started draining public coffers, including national health insurance and pension funds, to pay public sector salaries and service debt. In an extraordinary move, the prime minister issued a legislative decree in April to municipal governments and public entities, including hospitals and schools, to transfer their cash reserves to the Central Bank of Greece.

This was not popular, and the consequences were severe.

"The public hospitals are in dire crisis," explains Dimitris Sildiris, who owns a restaurant south of Athens. "My 83-year-old mother was recently admitted to Agios Pavlos hospital in Thessaloniki for kidney dialysis. They don't have basic supplies like medicines, bandages, bed linen, even toilet paper, and the patients' relatives have to fill the gap. Hospitals are even boiling hypodermic needles for re-use. This is explicitly forbidden and doesn't happen anywhere, not even in Africa! The fact that Syriza drew on hospital cash reserves to pay the debt is unforgivable."

Referendum

Tsipras went into office vowing to break the austerity chokehold Greece's creditors had placed the country in. But he also needed cash, and the troika insisted that Athens could only receive fresh loans if it committed to the austerity program.

Looking to break the stalemate, Tsipras announced a referendum for July 5, calling on voters to reject the creditors' proposal for further austerity measures in exchange for loan financing to Athens.

What followed can only be described as blatant political interference by European politicians and bureaucrats. They immediately framed the referendum as a vote on Greece's Eurozone membership, openly campaigning for both a Yes vote and the overthrow of the Syriza government.

But they didn't just campaign. When the referendum was announced, the European Central Bank tightened liquidity to the Greek banking system yet again, prompting the government to impose capital controls to prevent a months-long bank jog from becoming a bank run.

ATM cash withdrawals were limited to 60 euros per day. Retirees -- many of whom had become sole breadwinners for their families -- had to queue outside Bank of Greece branches on July 1 to withdraw just 120 euros of their monthly pension, without knowing when the remainder would be available.

Meanwhile, Greece's oligarch-owned corporate media aggressively spun a false narrative of a panicked public and widespread social unrest. Discredited former prime ministers went on TV to advocate a Yes vote as stations ran file footage presenting Turkish victims of the 1999 earthquake and account holders in the 2012 Cyprus banking crisis as distressed Greek pensioners.

Yet the resistance to austerity persisted. A June 29 rally for a No vote proved particularly extraordinary, not only for the sheer numbers and diversity of the crowd -- from toddlers to grandparents -- but because exactly four years earlier, over 100,000 people had gathered in the same spot to protest the first troika austerity measures. The second No rally held on July 3 was even bigger. At both rallies, the atmosphere in the jam-packed crowd was electric. Greeks had overcome fear. A new mood of defiance, empowerment, and celebration prevailed.

The result? An emphatic victory for the No side, with over 61 percent of Greeks voting to support their government's stance against the creditors.

Defeat

It was a triumphant moment, but it wasn't to last.

Tsipras took the referendum result to the Eurozone summit on Saturday, July 11 to strengthen Greece's hand in the negotiations, even as the ECB threatened to cut its lifeline to Greek banks without an agreement by Sunday night.

After a gruelling weekend of talks, Tsipras was presented with an ultimatum: Greece would either remain an indebted ward of Germany, the dominant Eurozone country, or face a disorderly exit from the Eurozone and the total collapse of the Greek banking system. After 17 hours of all-night talks, Tsipras signed the "agreement" shortly after dawn on Monday, albeit with a proverbial gun to his head.

Thus Greece ceded its sovereignty to its creditors, who now hold legislative and executive power in Greece. Germany now essentially controls Greece's finances and its banks -- and even has the power to veto Greek laws, since draft laws must be submitted for approval to creditors.

The business of the Greek parliament was reduced to rubber-stamping hundreds of new austerity laws that will gouge 12 billion euros from the depressed economy. It was these laws that Tsipras was charged with ushering through Athens, alienating and purging many of his own MPs and Central Commitee members in the process.

One particularly egregious set of provisions in the new memorandum marks 50 billion euros of Greek state assets -- from regional airports servicing busy tourist destinations (already snapped up by the German government firm Frapport) to utility companies and islands -- for transfer to a privatization fund under creditor control. An added clause prevents their future re-purchase, depriving Greece of strategic income-producing national assets.

It was an unambiguous defeat. They "crucified Tsipras in there" a Eurozone official attending the summit told the Financial Times.

Resilience

In Greece, reactions have been mixed. Many view Tsipras' capitulation as unavoidable under the circumstances, and they respect Syriza for fighting in Greece's corner until the bitter end.

Others say the ultimatum didn't occur in a vacuum. Both Tsipras and then-Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, critics counter, accepted most of the austerity measures at the start of negotiations, focusing instead on easing the rest while keeping Greece in the Eurozone. Crucially, they never questioned the legitimacy of the debt itself, despite the findings of the Preliminary Report of the Truth Committee on Public Debt, which concluded that the majority of Greek debt is illegal, odious, and unsustainable. And, they say, the Syriza leaders improvised their way through months of negotiations, draining the public coffers to service the debt while refusing to seriously prepare for a Eurozone exit should Germany's position prove intractable -- as it has been for five years. That effectively deprived Greece of its only real leverage in the negotiations, and left Greece at the mercy of the European Central Bank.

These critics see Tsipras more like Judas the betrayer than Christ the crucified. They lament that the Euro Summit "agreement" is far more extreme than the program Greek voters rejected on July 5. And they ask why Tsipras called a referendum if he wasn't prepared to honor the result.

"What does Tsipras think he's doing?" asks 29-year-old Ourania Tzavara, a bartender from Athens. "We voted no!"

"We do not have the right to turn the people's no into a yes," added former parliament speaker and Syriza MP Zoe Konstantopoulou, who will stand as an independent on September 20. "We have a duty to honor their verdict."

Exhausted by an 8-month-old government that brought a new memorandum instead of a new anti-austerity era -- and weary of frequent elections and governments that don't represent them -- a quarter of Greek voters polled in late August were undecided. By mid-September, Syriza and New Democracy -- the latter revived with a new leader from the old guard -- are both polling at around 27 percent. Some say they won't be voting, because regardless of who's in power, the outcome seems to be the same.

Yet Greeks remain determined to stop their free-fall into poverty, halt the mass exodus of their youth, and reclaim their future. "It's a huge blow but we have to re-group and keep going," says Irini Katsou, who co-owns the Athens restaurant with Sildiris. "Just because Tsipras surrendered doesn't mean that we have to."