In the United States, we often talk about poverty as a line: You are above it or below it; you escape it or can't get out of it. Every year, the government defines that line with a number. Right now, if you're in a family of four, you're considered poor if you get by on less than $16.60 per day.

What we tend to ignore, though -- and almost never bother to quantify -- is the vast spectrum of poverty itself. And that's why a new book, "$2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America," by Kathryn J. Edin and H. Luke Shaefer, is so eye-opening. It exposes in devastating detail the lives of millions of Americans who aren't just in poverty, but extreme poverty, the kind you'd normally associate with the developing world. Edin and Shaefer crunched census data and other numbers and calculated that 1.5 million American households are surviving on no more than $2 per day, per person. They also found that the number of households in such straits had doubled in the previous decade and a half.

It's worth pondering for a moment just how difficult it is to survive on $2 per day. That's a single gallon of gasoline. Or half a gallon of milk. If you took a D.C. bus this morning, you have 25 cents left for dinner. Among this group in extreme poverty, some get a boost from housing subsidies. Many collect food stamps -- an essential part of survival. But so complete is their destitution, they have little means to climb out. (The book described one woman who scored a job interview, couldn't afford transportation, walked 20 blocks to get there, and showed up looking haggard and drenched in sweat. She didn't get hired.)

Edin is a professor specializing in poverty at Johns Hopkins University. Shaefer is an associate professor of social work and public policy at the University of Michigan. In several years of research that led to this book, they set up field offices both urban and rural -- in Chicago, in Cleveland, in Johnson City, Tenn., in the Mississippi Delta -- and tried to document this jarring form of American poverty.

Here is what they found about the lives of the extreme poor:

1. Most are not receiving welfare assistance.

That is, essentially, the short explanation for why so many people are living virtually without cash in one of the world's most capitalist countries.

The United States, if you recall, reformed its welfare program in 1996, under Bill Clinton. The old system had some major problems, and cash handouts to the poor created a perverse incentive to stay unemployed. The program became associated with "indolence and single-parenthood," Edin and Shaefer write.

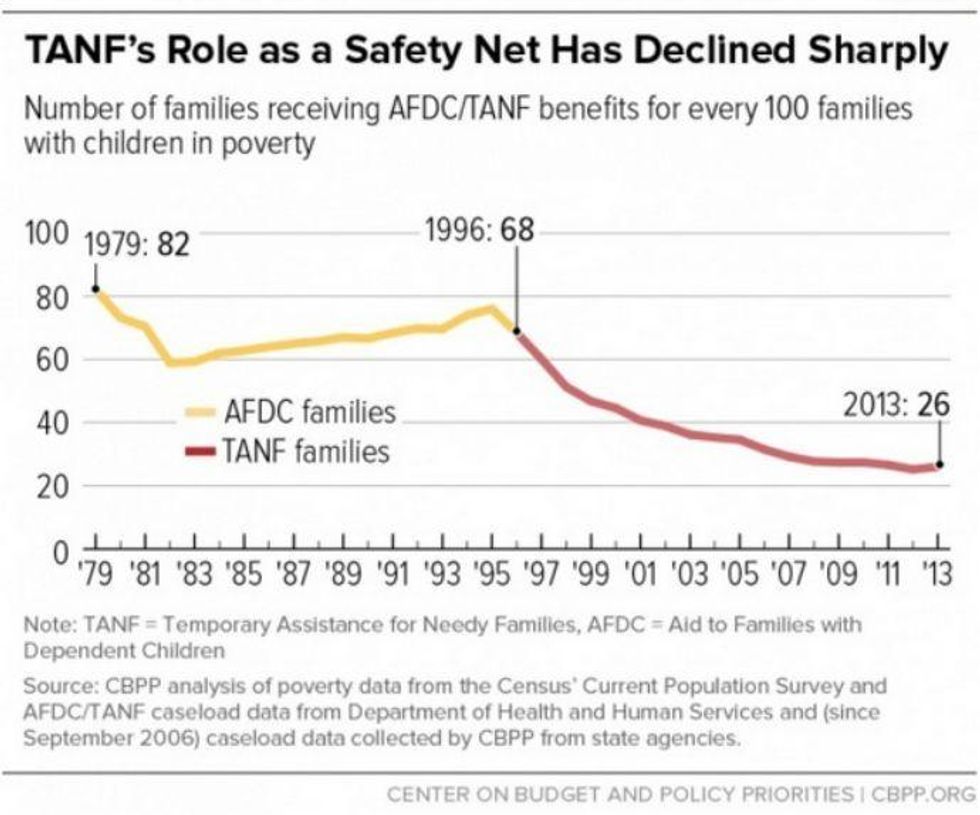

But the new program, known as the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (or TANF), has created an entirely different set of motivations. States have the option to use the federal money for ancillary programs (like child care) rather than simply doling out money to the poor. Only a small portion of the federal funding is used for traditional cash hand-outs, and states now have strong incentives to give it to people who already hold jobs. If you're jobless and out of money, you probably won't be helped by TANF.

In 1994, the old welfare program served 14.2 million people, two thirds of them children. Today's program serves 4.4 million, and Edin and Shaefer describe many extreme poor who believe the government is no longer giving out money at all. In a handful of states, fewer than 10 percent of poor households with children receive TANF benefits. In some poor communities, it's so hard to find TANF recipients that other families believe the government has exited the welfare business entirely; they never even apply.

Edin and Shaefer write that "welfare's extinction" has gone "virtually unnoticed" by the press and public, in part because the economy boomed right after the new legislation took effect. But now, the contours of the economy have changed, and jobs at the bottom provide less stability.

The government safety net has been "built on the assumption of full-time, stable employment at a living wage," the authors write. But the new labor market "fails to deliver on any of the above."

2. They depend on a shadow (and sometimes illegal) economy.

The characters in "$2 a Day" often go long periods virtually without any cash. But they also need to pay their bills. So they sell social security card numbers of their children (allowing others to reap the tax rewards). They purchase Kool-Aid, freeze it into popsicles, and sell the treats out of their home at a small profit. They trade their food stamps for cash -- at a brutal 60 cent-on-the-dollar exchange rate.

These practices have something in common: They are illegal. In the name of survival, the extreme poor get by with acts that make their stomachs churn. Edin said in an interview that this erodes their sense of self-worth, even if they don't get into legal trouble.

"We see parents making choices they themselves feel are objectionable," she said. "It adds to this feeling -- not only are you unemployed, but you're scum."

The authors describe in detail the mini-economy that has built up around SNAP (or food stamp) cards. Selling food stamps can result in a felony charge, and technology has made doing so more difficult. The "food stamps" are loaded onto EBT cards that require personal ID and pin numbers. Some who want to sell the value of their food stamps, then, simply make the deal with relatives. Others stand outside grocery stores and solicit shoppers; one buys the groceries, the other pays. In some communities, there might also be an opportunistic small store owner who is willing to help. As the book details:

The bodega owner will ring through, say, $100 in groceries and charge Jennifer's card that amount. But instead of walking out with the groceries, Jennifer will get, say, $60 in cash. The chief beneficiary of the exchange is not Jennifer but the store owner, who pockets $ 40 in profit (his price for the risk involved in the exchange).

3. They donate plasma as a way to get cash.

According to authors, this is a lifeline among the extreme poor: For those can't find jobs, they can still earn money by donating their plasma, a component in blood that is used by hospitals. The extreme poor show up at clinics, allow a needle to withdraw blood from a spot near the top of their forearm, and they walk away with $30 for three hours of their time. They're allowed by law to do this twice a week. No matter that donating sometimes comes with debilitating fatigue in the aftermath.

Many poor have "divots inside their elbow," Edin said in an interview, as a testament to the practice.

As far as cash-earning options go, plasma donation is among the most appealing -- and it's legal.

Edin said that she spent three summers working in Cleveland on this book. And one bus stop -- near 25th Street -- caught her attention. A plasma clinic was there. And that's where much of the bus emptied.

"Sure enough, the bus would stop and every person -- 20, 30 -- would go into that clinic," Edin said. "It was amazing how many families relied on giving plasma."

4. They aren't disconnected from the workforce.

Edin and Sheafer take pains to point this out, as if anticipating a reader reflex: Oh, these people just aren't trying to find jobs. In fact, they are. And in many cases, they held jobs, lost them, and then slid backward quickly. If you work a minimum wage job, for instance, you never accrue savings; if you lose that job, you have nothing to fall back on.

"The typical family in $2-a-day poverty is headed by an adult who works much of the time but has fallen on hard times," the authors write.

The problem, this book contends, is that the bottom of America's labor market has become more tenuous. Gone are the manufacturing giants who once provided nearly one-third of American jobs. Now, a new generation of U.S. workers depend on service sector positions that are often part-time or have varying hours. Many retailers now swell and shrink their staffs on an hourly basis, using computer algorithms that predict customer demand.

"The features of the worst jobs in the economy are a lot worse" than they were, Edin says.

So how might these varying hours translate into extreme poverty?

Let's say, for instance, you're working at a big retailer. Your hours fluctuate weekly -- and drastically so. Because food stamp benefits change along with income, every fluctuation must be reported to the Department of Human Services. If you work more hours one week and fail to report it, that's fraud -- even if you suspect the increase is temporary. You could go to jail, they authors write, or at minimum be forced to pay back the "excess" benefits.

So let's imagine a job where you work 30 hours one week and five the next. After a 30-hour week, SNAP benefits decline. But it might take the government weeks to adjust the benefits amount downward. This means the benefits could be trimmed just as you hit a 5-hour week, and suddenly you are without income or government support.

"Whatever can be said about the characteristics of the people who work low-wage jobs," the authors write, "it is also true that the jobs themselves too often set workers up for failure."