The Danger of 'Foreign Policy by Bumper Sticker'

Appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1966, George F. Kennan, the legendary Cold War diplomat often called "the father of containment," criticized the escalation of the war in Vietnam. The United States, he said, should not "jump around like an elephant frightened by a mouse."

Appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1966, George F. Kennan, the legendary Cold War diplomat often called "the father of containment," criticized the escalation of the war in Vietnam. The United States, he said, should not "jump around like an elephant frightened by a mouse."

Kennan's "frightened elephant" is a strangely apt metaphor for the situation in which we find ourselves nearly a half-century later. In the GOP primary, the candidates are calling for a foreign policy defined by fear-mongering and senseless aggression. Their agenda includes plans to reverse President Obama's nuclear agreement with Iran, abandon renewed diplomatic ties with Cuba, escalate tensions with Russia and deploy U.S. troops in Syria. Much like Kennan's agitated elephant, the Republicans candidates see threats in Iran, Vladimir Putin's Russia, Bashar al-Assad's Syria and in the Islamic State and other Islamic extremist groups that are far out of proportion to any real harm they could ever inflict on U.S. interests. They are so out of touch with reality that even admitting the folly of the Iraq war has become a sign of weakness. The far greater danger, though, is the combination of paranoia and hubris that characterizes the foreign policies of the Republican candidates leading us into yet another self-inflicted foreign policy disaster. Once again, they would have us rush to embrace unnecessarily militaristic responses to otherwise manageable foreign policy challenges, bringing yet more chaos to the Middle East and Eastern Europe while costing the nation even more in lost lives and treasure.

In the latest issue of the National Interest, Richard Burt and Dimitri Simes provide a corrective to foreign policy recklessness. "[T]he debate over international affairs is now badly debased," they declare in the lead editorial, titled "Foreign Policy by Bumper Sticker." "The quality of America's foreign-policy discussion has demonstrably deteriorated over the last thirty years." Remarking on the GOP primary in particular, the authors noted that "the very warrior intellectuals who were directly responsible for today's state of affairs" in Iraq and the Middle East "dominate the foreign-policy advisory groups of nearly all the Republican candidates."

Founded in 1985 by the late Irving Kristol, one of the original leaders in neoconservative thinking, the National Interest served as a forum for vigorous debate among conservative intellectuals and policymakers until the George W. Bush administration, when editorials critical of the Iraq war led to the departure of several of the magazine's most prominent neoconservative voices. Today the journal is one of the last bastions of "realist" foreign policy thinking, or the belief that U.S. vital interests should trump ideology in our approach to international affairs. Meanwhile, three decades after the National Interest's inception, the assumptions governing U.S. foreign policy are the antithesis of sensible realism. With few exceptions, the political and media elite have accepted as a given the principle that the United States has the right and the responsibility to police the world -- to make and enforce the rules by which other nations must abide, even if we don't. In the words of former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, "We are the indispensable nation."

As Burt and Simes write, "America's new foreign-policy establishment has adopted a simplistic, moralistic and triumphalist mind-set." And while Democratic leaders in some cases have embraced diplomacy as an alternative to military force and intimidation -- namely in Cuba and more recently toward Iran -- the party remains dominated by liberal interventionists who share the neoconservative penchant for triumphalism, as evidenced by much of the party's misguided positions on Ukraine and Syria and support for the military intervention in Libya.

In 2010, for example, Hillary Clinton delivered what the New York Times described as a "an unalloyed statement of American might." Pronouncing the arrival of a "new American moment," Clinton declared, "let me say it clearly: The United States can, must, and will lead in this new century." More recently, a group of Senate Democrats led by Chris Murphy (Conn.) outlined their vision for a progressive approach to foreign policy -- and while the statement included some useful markers, it took a similar view of America's global role. "The new world order demands that the United States think anew about the tools that it will use to lead the world," they argued.

Reconsidering the tools at the United States' disposal, and ensuring that military action is used only as a last resort, is a welcome start. However, our public discourse should also include a robust debate about not the means but the ends of our foreign policy. What should be our goals and priorities -- and how do we reconcile these goals and priorities with those of other powers? As author James Mann wrote last year, "We seem unable to acknowledge to ourselves that other nations of the world do not always need us as a leader in exactly the same way they did in 1945 or 1989. Moreover, in resolving international crises, other nations have become indispensable to the United States, too--far more than they were in the recent past." The Iran deal -- a U.S. priority that would not have been possible without the cooperation of Russia and China -- perfectly illustrates Mann's point.

But without facing meaningful consequences for reckless triumphalism, politicians have little incentive to break with the prevailing orthodoxy, especially when questioning America's "indispensable" role inevitably results in attacks on their patriotism. The unfortunate reality, as Burt and Simes observed, is that many policymakers "accept this form of intimidation by interventionists who substitute chest-thumping for coherent and serious, historically grounded arguments," while much of the media simply "lacks the interest and the expertise" to present alternative views.

As editor of the Nation, a magazine with a long history of adopting alternative views and unpopular stances on foreign policy (that were later viewed as common sense), I appreciate the importance of challenging the conventional wisdom. I'm also acutely aware of how difficult it has become in today's toxic media environment to speak out on certain issues. As Burt and Simes noted, "Prominent voices dismiss those raising" concerns about "costly international interventions when vital national interests are not at stake" as "cynical realists, isolationists or, more recently, unpatriotic Putin apologists." This is a form of neo-McCarthyism that deforms our discourse.

So it's heartening that establishment figures such as Robert Legvold, former director of Columbia University's Harriman Institute, are now rightly noting that "degrading the discourse in the United States and coarsening the way the discussion is conducted are clearly not in the country's interest. One would hope," he adds, that "responsible parts of the media will begin speaking out against these trends."

There are indeed challenges that require U.S. action. From chaos in the Middle East to a new Cold War to the great transformation that is beginning in China, the world is only getting more complicated. But we need to separate the mice from the real challenges, and that requires a more thoughtful discourse. In 2016, and beyond, we need a foreign policy discussion as serious as the challenges we face, not as agitated as the crises we have helped manufacture.

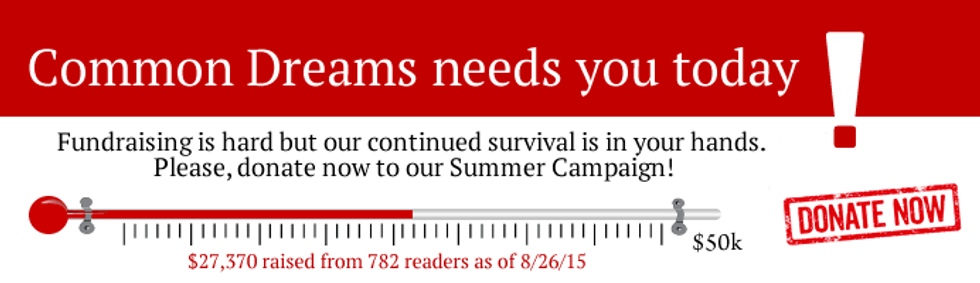

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1966, George F. Kennan, the legendary Cold War diplomat often called "the father of containment," criticized the escalation of the war in Vietnam. The United States, he said, should not "jump around like an elephant frightened by a mouse."

Kennan's "frightened elephant" is a strangely apt metaphor for the situation in which we find ourselves nearly a half-century later. In the GOP primary, the candidates are calling for a foreign policy defined by fear-mongering and senseless aggression. Their agenda includes plans to reverse President Obama's nuclear agreement with Iran, abandon renewed diplomatic ties with Cuba, escalate tensions with Russia and deploy U.S. troops in Syria. Much like Kennan's agitated elephant, the Republicans candidates see threats in Iran, Vladimir Putin's Russia, Bashar al-Assad's Syria and in the Islamic State and other Islamic extremist groups that are far out of proportion to any real harm they could ever inflict on U.S. interests. They are so out of touch with reality that even admitting the folly of the Iraq war has become a sign of weakness. The far greater danger, though, is the combination of paranoia and hubris that characterizes the foreign policies of the Republican candidates leading us into yet another self-inflicted foreign policy disaster. Once again, they would have us rush to embrace unnecessarily militaristic responses to otherwise manageable foreign policy challenges, bringing yet more chaos to the Middle East and Eastern Europe while costing the nation even more in lost lives and treasure.

In the latest issue of the National Interest, Richard Burt and Dimitri Simes provide a corrective to foreign policy recklessness. "[T]he debate over international affairs is now badly debased," they declare in the lead editorial, titled "Foreign Policy by Bumper Sticker." "The quality of America's foreign-policy discussion has demonstrably deteriorated over the last thirty years." Remarking on the GOP primary in particular, the authors noted that "the very warrior intellectuals who were directly responsible for today's state of affairs" in Iraq and the Middle East "dominate the foreign-policy advisory groups of nearly all the Republican candidates."

Founded in 1985 by the late Irving Kristol, one of the original leaders in neoconservative thinking, the National Interest served as a forum for vigorous debate among conservative intellectuals and policymakers until the George W. Bush administration, when editorials critical of the Iraq war led to the departure of several of the magazine's most prominent neoconservative voices. Today the journal is one of the last bastions of "realist" foreign policy thinking, or the belief that U.S. vital interests should trump ideology in our approach to international affairs. Meanwhile, three decades after the National Interest's inception, the assumptions governing U.S. foreign policy are the antithesis of sensible realism. With few exceptions, the political and media elite have accepted as a given the principle that the United States has the right and the responsibility to police the world -- to make and enforce the rules by which other nations must abide, even if we don't. In the words of former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, "We are the indispensable nation."

As Burt and Simes write, "America's new foreign-policy establishment has adopted a simplistic, moralistic and triumphalist mind-set." And while Democratic leaders in some cases have embraced diplomacy as an alternative to military force and intimidation -- namely in Cuba and more recently toward Iran -- the party remains dominated by liberal interventionists who share the neoconservative penchant for triumphalism, as evidenced by much of the party's misguided positions on Ukraine and Syria and support for the military intervention in Libya.

In 2010, for example, Hillary Clinton delivered what the New York Times described as a "an unalloyed statement of American might." Pronouncing the arrival of a "new American moment," Clinton declared, "let me say it clearly: The United States can, must, and will lead in this new century." More recently, a group of Senate Democrats led by Chris Murphy (Conn.) outlined their vision for a progressive approach to foreign policy -- and while the statement included some useful markers, it took a similar view of America's global role. "The new world order demands that the United States think anew about the tools that it will use to lead the world," they argued.

Reconsidering the tools at the United States' disposal, and ensuring that military action is used only as a last resort, is a welcome start. However, our public discourse should also include a robust debate about not the means but the ends of our foreign policy. What should be our goals and priorities -- and how do we reconcile these goals and priorities with those of other powers? As author James Mann wrote last year, "We seem unable to acknowledge to ourselves that other nations of the world do not always need us as a leader in exactly the same way they did in 1945 or 1989. Moreover, in resolving international crises, other nations have become indispensable to the United States, too--far more than they were in the recent past." The Iran deal -- a U.S. priority that would not have been possible without the cooperation of Russia and China -- perfectly illustrates Mann's point.

But without facing meaningful consequences for reckless triumphalism, politicians have little incentive to break with the prevailing orthodoxy, especially when questioning America's "indispensable" role inevitably results in attacks on their patriotism. The unfortunate reality, as Burt and Simes observed, is that many policymakers "accept this form of intimidation by interventionists who substitute chest-thumping for coherent and serious, historically grounded arguments," while much of the media simply "lacks the interest and the expertise" to present alternative views.

As editor of the Nation, a magazine with a long history of adopting alternative views and unpopular stances on foreign policy (that were later viewed as common sense), I appreciate the importance of challenging the conventional wisdom. I'm also acutely aware of how difficult it has become in today's toxic media environment to speak out on certain issues. As Burt and Simes noted, "Prominent voices dismiss those raising" concerns about "costly international interventions when vital national interests are not at stake" as "cynical realists, isolationists or, more recently, unpatriotic Putin apologists." This is a form of neo-McCarthyism that deforms our discourse.

So it's heartening that establishment figures such as Robert Legvold, former director of Columbia University's Harriman Institute, are now rightly noting that "degrading the discourse in the United States and coarsening the way the discussion is conducted are clearly not in the country's interest. One would hope," he adds, that "responsible parts of the media will begin speaking out against these trends."

There are indeed challenges that require U.S. action. From chaos in the Middle East to a new Cold War to the great transformation that is beginning in China, the world is only getting more complicated. But we need to separate the mice from the real challenges, and that requires a more thoughtful discourse. In 2016, and beyond, we need a foreign policy discussion as serious as the challenges we face, not as agitated as the crises we have helped manufacture.

Appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1966, George F. Kennan, the legendary Cold War diplomat often called "the father of containment," criticized the escalation of the war in Vietnam. The United States, he said, should not "jump around like an elephant frightened by a mouse."

Kennan's "frightened elephant" is a strangely apt metaphor for the situation in which we find ourselves nearly a half-century later. In the GOP primary, the candidates are calling for a foreign policy defined by fear-mongering and senseless aggression. Their agenda includes plans to reverse President Obama's nuclear agreement with Iran, abandon renewed diplomatic ties with Cuba, escalate tensions with Russia and deploy U.S. troops in Syria. Much like Kennan's agitated elephant, the Republicans candidates see threats in Iran, Vladimir Putin's Russia, Bashar al-Assad's Syria and in the Islamic State and other Islamic extremist groups that are far out of proportion to any real harm they could ever inflict on U.S. interests. They are so out of touch with reality that even admitting the folly of the Iraq war has become a sign of weakness. The far greater danger, though, is the combination of paranoia and hubris that characterizes the foreign policies of the Republican candidates leading us into yet another self-inflicted foreign policy disaster. Once again, they would have us rush to embrace unnecessarily militaristic responses to otherwise manageable foreign policy challenges, bringing yet more chaos to the Middle East and Eastern Europe while costing the nation even more in lost lives and treasure.

In the latest issue of the National Interest, Richard Burt and Dimitri Simes provide a corrective to foreign policy recklessness. "[T]he debate over international affairs is now badly debased," they declare in the lead editorial, titled "Foreign Policy by Bumper Sticker." "The quality of America's foreign-policy discussion has demonstrably deteriorated over the last thirty years." Remarking on the GOP primary in particular, the authors noted that "the very warrior intellectuals who were directly responsible for today's state of affairs" in Iraq and the Middle East "dominate the foreign-policy advisory groups of nearly all the Republican candidates."

Founded in 1985 by the late Irving Kristol, one of the original leaders in neoconservative thinking, the National Interest served as a forum for vigorous debate among conservative intellectuals and policymakers until the George W. Bush administration, when editorials critical of the Iraq war led to the departure of several of the magazine's most prominent neoconservative voices. Today the journal is one of the last bastions of "realist" foreign policy thinking, or the belief that U.S. vital interests should trump ideology in our approach to international affairs. Meanwhile, three decades after the National Interest's inception, the assumptions governing U.S. foreign policy are the antithesis of sensible realism. With few exceptions, the political and media elite have accepted as a given the principle that the United States has the right and the responsibility to police the world -- to make and enforce the rules by which other nations must abide, even if we don't. In the words of former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, "We are the indispensable nation."

As Burt and Simes write, "America's new foreign-policy establishment has adopted a simplistic, moralistic and triumphalist mind-set." And while Democratic leaders in some cases have embraced diplomacy as an alternative to military force and intimidation -- namely in Cuba and more recently toward Iran -- the party remains dominated by liberal interventionists who share the neoconservative penchant for triumphalism, as evidenced by much of the party's misguided positions on Ukraine and Syria and support for the military intervention in Libya.

In 2010, for example, Hillary Clinton delivered what the New York Times described as a "an unalloyed statement of American might." Pronouncing the arrival of a "new American moment," Clinton declared, "let me say it clearly: The United States can, must, and will lead in this new century." More recently, a group of Senate Democrats led by Chris Murphy (Conn.) outlined their vision for a progressive approach to foreign policy -- and while the statement included some useful markers, it took a similar view of America's global role. "The new world order demands that the United States think anew about the tools that it will use to lead the world," they argued.

Reconsidering the tools at the United States' disposal, and ensuring that military action is used only as a last resort, is a welcome start. However, our public discourse should also include a robust debate about not the means but the ends of our foreign policy. What should be our goals and priorities -- and how do we reconcile these goals and priorities with those of other powers? As author James Mann wrote last year, "We seem unable to acknowledge to ourselves that other nations of the world do not always need us as a leader in exactly the same way they did in 1945 or 1989. Moreover, in resolving international crises, other nations have become indispensable to the United States, too--far more than they were in the recent past." The Iran deal -- a U.S. priority that would not have been possible without the cooperation of Russia and China -- perfectly illustrates Mann's point.

But without facing meaningful consequences for reckless triumphalism, politicians have little incentive to break with the prevailing orthodoxy, especially when questioning America's "indispensable" role inevitably results in attacks on their patriotism. The unfortunate reality, as Burt and Simes observed, is that many policymakers "accept this form of intimidation by interventionists who substitute chest-thumping for coherent and serious, historically grounded arguments," while much of the media simply "lacks the interest and the expertise" to present alternative views.

As editor of the Nation, a magazine with a long history of adopting alternative views and unpopular stances on foreign policy (that were later viewed as common sense), I appreciate the importance of challenging the conventional wisdom. I'm also acutely aware of how difficult it has become in today's toxic media environment to speak out on certain issues. As Burt and Simes noted, "Prominent voices dismiss those raising" concerns about "costly international interventions when vital national interests are not at stake" as "cynical realists, isolationists or, more recently, unpatriotic Putin apologists." This is a form of neo-McCarthyism that deforms our discourse.

So it's heartening that establishment figures such as Robert Legvold, former director of Columbia University's Harriman Institute, are now rightly noting that "degrading the discourse in the United States and coarsening the way the discussion is conducted are clearly not in the country's interest. One would hope," he adds, that "responsible parts of the media will begin speaking out against these trends."

There are indeed challenges that require U.S. action. From chaos in the Middle East to a new Cold War to the great transformation that is beginning in China, the world is only getting more complicated. But we need to separate the mice from the real challenges, and that requires a more thoughtful discourse. In 2016, and beyond, we need a foreign policy discussion as serious as the challenges we face, not as agitated as the crises we have helped manufacture.