A Kerfuffle Over Global Wealth Stats

Can we trust Oxfam’s latest numbers on global inequality? Critics don’t think we should. But their pushback is getting pushback aplenty.

Sometimes facts can fly. All around the world.

Over the last year or so, no one has been flying facts more effectively than the folks at Oxfam, the activist global charity. A year ago, an Oxfam report revealed that the world's 85 richest billionaires had as much wealth as the poorest half of the world's population. That stat went viral overnight.

Earlier this month, on the eve of the annual Davos summit of the world's rich and powerful, Oxfam came back with more. In 2014, the charity reported, we only needed to tally up the fortunes of the world's 80 richest billionaires to match the wealth of the world's poorest half.

Oxfam's latest analysis of world wealth, Wealth: Having It All and Wanting More, went on to add an even more startling stat: If current trends continue, the world's top 1 percent will have more wealth than all the rest of the world combined by the end of next year.

These incredibly dramatic figures promptly made headlines everywhere -- and almost just as quickly drew some prominent pushback. Two of the world's top policy wonks -- Felix Salmon of Reuters and former Washington Post analyst Ezra Klein, now of Vox -- came out with columns that sought to shoot the new Oxfam numbers down.

Oxfam's statistical case, charged Klein, "has deep flaws." Oxfam, Salmon pounded out on his keyboard, was engaging in "a silly and pointless exercise."

Both Salmon and Klein have the same basic point to make: Oxfam is including in the ranks of the world's poorest millions of people who can't possibly be considered poor.

These suspect poor come from the developed world. Many of them have incomes that tower above the miniscule incomes common in the developing world. But they also have more debts than assets. That gives them a negative net worth and places them in the poorest tenth -- or decile, as the statisticians like to say -- of the world's population.

The sum total of all this negative net worth from the developed world, the Salmon and Klein critique goes, distorts the inequality picture that Oxfam is trying to paint.

Huffs Salmon: "My niece, who just got her first 50 cents in pocket money, has more money than the poorest 2 billion people in the world combined."

Oxfam, critics charge, is including in the ranks of the world's poorest millions of people who can't possibly be considered poor.

"Stop adding up the wealth of the poor," one headline on Salmon's piece pleads. Any numbers this addition generates will always be terribly "misleading."

So should you feel misled? I certainly don't feel that way. And you shouldn't either.

The researchers at Oxfam have supplied one reason why in their response to Salmon and Klein. That reason: Excluding the world's poorest net worth decile from the Oxfam analysis -- that decile with all the negative net worth of the developed world's overindebted -- still generates statistics that rate as incredibly dramatic in anybody's book.

The four deciles just above the bottom tenth that Salmon and Klein are contesting hold none of the developed world's negative-worth crowd. The people in these four deciles turn out to have about the same amount of wealth as the 147 wealthiest billionaires on the Forbes list of the world's richest.

"That means," notes Oxfam's Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva, "that two busloads of billionaires control the same wealth as, at least, 40 percent of the world."

Excluding the bottom decile from the analysis makes even less a difference on the top 1 percent's share of global wealth. In the original Oxfam analysis, with the bottom decile included, the top 1 percent last year held a 48.1 percent global wealth share. With the bottom decile excluded, the top 1 percent share drops all the way down to . . . 47.9 percent.

The Oxfam numbers, notes the group's Nick Galasso, "hold up."

The best defense of the Oxfam analysis may actually have come from outside Oxfam's ranks.

But the best defense of the Oxfam analysis may actually have come from outside Oxfam's ranks, from Branko Milanovic, the City of New York Graduate Center scholar who formerly served as the World Bank's lead research economist.

Milanovic today ranks as one of research world's most well-respected experts on global wealth distribution. Last fall, his rave review of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century started the buzz that turned that book into an international bestseller.

Yes, Milanovic notes in his response to the Salmon-Klein case, we do have "wealth-poor people" from developed nations who "do not necessarily lead a life of poverty." The developed world's financial systems, he explains, let people in rich nations "borrow and keep their consumption relatively high all the while driving their net wealth down."

But this reality in no way invalidates -- or scars as "silly" -- studies of wealth inequality along the line of what Oxfam has generated. We have different ways of looking at inequality, Milanovic points out. Each has its uses.

If, for instance, you want to look at people "who live at the edge of subsistence," then you shouldn't look at net worth. You should look at the global distribution of consumption, at how many people are living below $1.25 per day, as the World Bank and other agencies do.

But if you want to look at economic and political power, you need to look at the distribution of wealth. The "players" who matter most in the world today have staggeringly disproportionate quantities of it.

If you want to look at economic and political power, you need to look at wealth distribution.

Ezra Klein, interestingly, does get this power point. Oxfam's numbers, he acknowledges, do point toward "who has the ability to use wealth as a discretionary power resource."

"The top one percent controls an eye-popping amount of global wealth," Klein notes, "but more to the point, they're the ones who have much more wealth than they have debt -- and so they're the ones who can deploy their excess wealth towards discretionary ends like electing political candidates and lobbying legislatures."

So maybe we don't have such a big kerfuffle here after all. Maybe now we can step out of the statistical swamp and start talking about what we need to do about shearing the super rich down to democratic size.

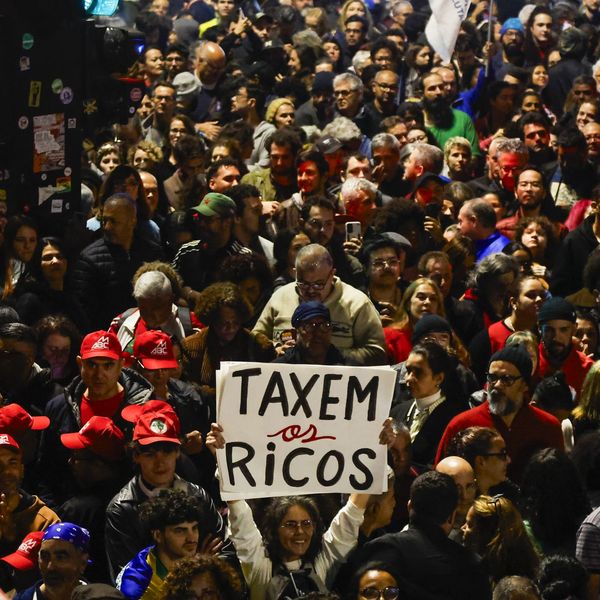

Oxfam can help here, too. The group's new study and the Even It Up campaign Oxfam launched this past October both offer up a comprehensive set of proposals, everything from wealth taxes to going after tax havens with international sanctions.

Among the boldest initiatives on the Oxfam list: establishing what amounts to a maximum wage, by moving our corporations "towards a highest-to-median pay ratio of 20:1."

Oxfam's high-flying stats are shoving ideas like this pay-ratio maximum onto the global political stage. Let's keep them flying!

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Sometimes facts can fly. All around the world.

Over the last year or so, no one has been flying facts more effectively than the folks at Oxfam, the activist global charity. A year ago, an Oxfam report revealed that the world's 85 richest billionaires had as much wealth as the poorest half of the world's population. That stat went viral overnight.

Earlier this month, on the eve of the annual Davos summit of the world's rich and powerful, Oxfam came back with more. In 2014, the charity reported, we only needed to tally up the fortunes of the world's 80 richest billionaires to match the wealth of the world's poorest half.

Oxfam's latest analysis of world wealth, Wealth: Having It All and Wanting More, went on to add an even more startling stat: If current trends continue, the world's top 1 percent will have more wealth than all the rest of the world combined by the end of next year.

These incredibly dramatic figures promptly made headlines everywhere -- and almost just as quickly drew some prominent pushback. Two of the world's top policy wonks -- Felix Salmon of Reuters and former Washington Post analyst Ezra Klein, now of Vox -- came out with columns that sought to shoot the new Oxfam numbers down.

Oxfam's statistical case, charged Klein, "has deep flaws." Oxfam, Salmon pounded out on his keyboard, was engaging in "a silly and pointless exercise."

Both Salmon and Klein have the same basic point to make: Oxfam is including in the ranks of the world's poorest millions of people who can't possibly be considered poor.

These suspect poor come from the developed world. Many of them have incomes that tower above the miniscule incomes common in the developing world. But they also have more debts than assets. That gives them a negative net worth and places them in the poorest tenth -- or decile, as the statisticians like to say -- of the world's population.

The sum total of all this negative net worth from the developed world, the Salmon and Klein critique goes, distorts the inequality picture that Oxfam is trying to paint.

Huffs Salmon: "My niece, who just got her first 50 cents in pocket money, has more money than the poorest 2 billion people in the world combined."

Oxfam, critics charge, is including in the ranks of the world's poorest millions of people who can't possibly be considered poor.

"Stop adding up the wealth of the poor," one headline on Salmon's piece pleads. Any numbers this addition generates will always be terribly "misleading."

So should you feel misled? I certainly don't feel that way. And you shouldn't either.

The researchers at Oxfam have supplied one reason why in their response to Salmon and Klein. That reason: Excluding the world's poorest net worth decile from the Oxfam analysis -- that decile with all the negative net worth of the developed world's overindebted -- still generates statistics that rate as incredibly dramatic in anybody's book.

The four deciles just above the bottom tenth that Salmon and Klein are contesting hold none of the developed world's negative-worth crowd. The people in these four deciles turn out to have about the same amount of wealth as the 147 wealthiest billionaires on the Forbes list of the world's richest.

"That means," notes Oxfam's Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva, "that two busloads of billionaires control the same wealth as, at least, 40 percent of the world."

Excluding the bottom decile from the analysis makes even less a difference on the top 1 percent's share of global wealth. In the original Oxfam analysis, with the bottom decile included, the top 1 percent last year held a 48.1 percent global wealth share. With the bottom decile excluded, the top 1 percent share drops all the way down to . . . 47.9 percent.

The Oxfam numbers, notes the group's Nick Galasso, "hold up."

The best defense of the Oxfam analysis may actually have come from outside Oxfam's ranks.

But the best defense of the Oxfam analysis may actually have come from outside Oxfam's ranks, from Branko Milanovic, the City of New York Graduate Center scholar who formerly served as the World Bank's lead research economist.

Milanovic today ranks as one of research world's most well-respected experts on global wealth distribution. Last fall, his rave review of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century started the buzz that turned that book into an international bestseller.

Yes, Milanovic notes in his response to the Salmon-Klein case, we do have "wealth-poor people" from developed nations who "do not necessarily lead a life of poverty." The developed world's financial systems, he explains, let people in rich nations "borrow and keep their consumption relatively high all the while driving their net wealth down."

But this reality in no way invalidates -- or scars as "silly" -- studies of wealth inequality along the line of what Oxfam has generated. We have different ways of looking at inequality, Milanovic points out. Each has its uses.

If, for instance, you want to look at people "who live at the edge of subsistence," then you shouldn't look at net worth. You should look at the global distribution of consumption, at how many people are living below $1.25 per day, as the World Bank and other agencies do.

But if you want to look at economic and political power, you need to look at the distribution of wealth. The "players" who matter most in the world today have staggeringly disproportionate quantities of it.

If you want to look at economic and political power, you need to look at wealth distribution.

Ezra Klein, interestingly, does get this power point. Oxfam's numbers, he acknowledges, do point toward "who has the ability to use wealth as a discretionary power resource."

"The top one percent controls an eye-popping amount of global wealth," Klein notes, "but more to the point, they're the ones who have much more wealth than they have debt -- and so they're the ones who can deploy their excess wealth towards discretionary ends like electing political candidates and lobbying legislatures."

So maybe we don't have such a big kerfuffle here after all. Maybe now we can step out of the statistical swamp and start talking about what we need to do about shearing the super rich down to democratic size.

Oxfam can help here, too. The group's new study and the Even It Up campaign Oxfam launched this past October both offer up a comprehensive set of proposals, everything from wealth taxes to going after tax havens with international sanctions.

Among the boldest initiatives on the Oxfam list: establishing what amounts to a maximum wage, by moving our corporations "towards a highest-to-median pay ratio of 20:1."

Oxfam's high-flying stats are shoving ideas like this pay-ratio maximum onto the global political stage. Let's keep them flying!

Sometimes facts can fly. All around the world.

Over the last year or so, no one has been flying facts more effectively than the folks at Oxfam, the activist global charity. A year ago, an Oxfam report revealed that the world's 85 richest billionaires had as much wealth as the poorest half of the world's population. That stat went viral overnight.

Earlier this month, on the eve of the annual Davos summit of the world's rich and powerful, Oxfam came back with more. In 2014, the charity reported, we only needed to tally up the fortunes of the world's 80 richest billionaires to match the wealth of the world's poorest half.

Oxfam's latest analysis of world wealth, Wealth: Having It All and Wanting More, went on to add an even more startling stat: If current trends continue, the world's top 1 percent will have more wealth than all the rest of the world combined by the end of next year.

These incredibly dramatic figures promptly made headlines everywhere -- and almost just as quickly drew some prominent pushback. Two of the world's top policy wonks -- Felix Salmon of Reuters and former Washington Post analyst Ezra Klein, now of Vox -- came out with columns that sought to shoot the new Oxfam numbers down.

Oxfam's statistical case, charged Klein, "has deep flaws." Oxfam, Salmon pounded out on his keyboard, was engaging in "a silly and pointless exercise."

Both Salmon and Klein have the same basic point to make: Oxfam is including in the ranks of the world's poorest millions of people who can't possibly be considered poor.

These suspect poor come from the developed world. Many of them have incomes that tower above the miniscule incomes common in the developing world. But they also have more debts than assets. That gives them a negative net worth and places them in the poorest tenth -- or decile, as the statisticians like to say -- of the world's population.

The sum total of all this negative net worth from the developed world, the Salmon and Klein critique goes, distorts the inequality picture that Oxfam is trying to paint.

Huffs Salmon: "My niece, who just got her first 50 cents in pocket money, has more money than the poorest 2 billion people in the world combined."

Oxfam, critics charge, is including in the ranks of the world's poorest millions of people who can't possibly be considered poor.

"Stop adding up the wealth of the poor," one headline on Salmon's piece pleads. Any numbers this addition generates will always be terribly "misleading."

So should you feel misled? I certainly don't feel that way. And you shouldn't either.

The researchers at Oxfam have supplied one reason why in their response to Salmon and Klein. That reason: Excluding the world's poorest net worth decile from the Oxfam analysis -- that decile with all the negative net worth of the developed world's overindebted -- still generates statistics that rate as incredibly dramatic in anybody's book.

The four deciles just above the bottom tenth that Salmon and Klein are contesting hold none of the developed world's negative-worth crowd. The people in these four deciles turn out to have about the same amount of wealth as the 147 wealthiest billionaires on the Forbes list of the world's richest.

"That means," notes Oxfam's Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva, "that two busloads of billionaires control the same wealth as, at least, 40 percent of the world."

Excluding the bottom decile from the analysis makes even less a difference on the top 1 percent's share of global wealth. In the original Oxfam analysis, with the bottom decile included, the top 1 percent last year held a 48.1 percent global wealth share. With the bottom decile excluded, the top 1 percent share drops all the way down to . . . 47.9 percent.

The Oxfam numbers, notes the group's Nick Galasso, "hold up."

The best defense of the Oxfam analysis may actually have come from outside Oxfam's ranks.

But the best defense of the Oxfam analysis may actually have come from outside Oxfam's ranks, from Branko Milanovic, the City of New York Graduate Center scholar who formerly served as the World Bank's lead research economist.

Milanovic today ranks as one of research world's most well-respected experts on global wealth distribution. Last fall, his rave review of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century started the buzz that turned that book into an international bestseller.

Yes, Milanovic notes in his response to the Salmon-Klein case, we do have "wealth-poor people" from developed nations who "do not necessarily lead a life of poverty." The developed world's financial systems, he explains, let people in rich nations "borrow and keep their consumption relatively high all the while driving their net wealth down."

But this reality in no way invalidates -- or scars as "silly" -- studies of wealth inequality along the line of what Oxfam has generated. We have different ways of looking at inequality, Milanovic points out. Each has its uses.

If, for instance, you want to look at people "who live at the edge of subsistence," then you shouldn't look at net worth. You should look at the global distribution of consumption, at how many people are living below $1.25 per day, as the World Bank and other agencies do.

But if you want to look at economic and political power, you need to look at the distribution of wealth. The "players" who matter most in the world today have staggeringly disproportionate quantities of it.

If you want to look at economic and political power, you need to look at wealth distribution.

Ezra Klein, interestingly, does get this power point. Oxfam's numbers, he acknowledges, do point toward "who has the ability to use wealth as a discretionary power resource."

"The top one percent controls an eye-popping amount of global wealth," Klein notes, "but more to the point, they're the ones who have much more wealth than they have debt -- and so they're the ones who can deploy their excess wealth towards discretionary ends like electing political candidates and lobbying legislatures."

So maybe we don't have such a big kerfuffle here after all. Maybe now we can step out of the statistical swamp and start talking about what we need to do about shearing the super rich down to democratic size.

Oxfam can help here, too. The group's new study and the Even It Up campaign Oxfam launched this past October both offer up a comprehensive set of proposals, everything from wealth taxes to going after tax havens with international sanctions.

Among the boldest initiatives on the Oxfam list: establishing what amounts to a maximum wage, by moving our corporations "towards a highest-to-median pay ratio of 20:1."

Oxfam's high-flying stats are shoving ideas like this pay-ratio maximum onto the global political stage. Let's keep them flying!