When a grand jury decided not to indict a Ferguson, Mo., police officer in the killing of unarmed teenager Michael Brown, Brooklyn resident Jon Robinson declined to join the public protests. Two weeks later, when a Staten Island grand jury failed to indict the New York police officer who was filmed choking Eric Garner to death, Robinson marched through the night, though he remained uncertain of what the protests would accomplish. "I've got this rage and hunger for change," he told a reporter. "But I also don't know how you really cause change when you've got a system so broken."

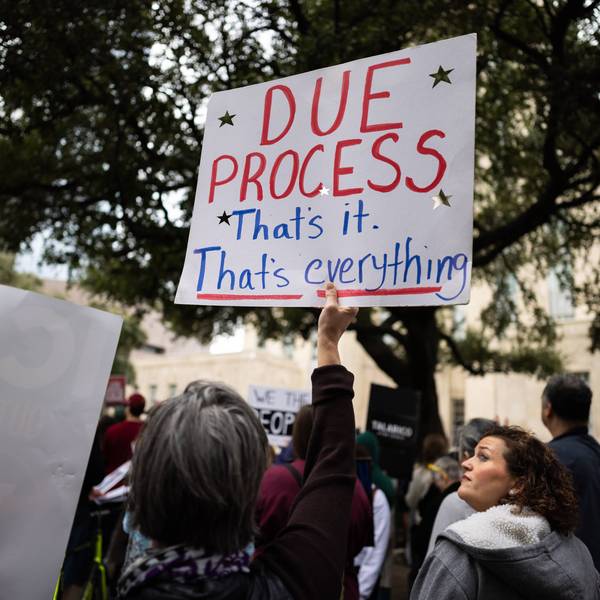

That sense of despair is understandable, given the recent spate of incidents in which black lives have been stolen without any justification or justice. But there are signs that the passion in the streets, which was on display this past weekend as tens of thousands of protesters marched through New York, the District and other cities across the country, could translate into meaningful policy changes. Last week, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman called on Gov. Andrew Cuomo to give his office the power to investigate and prosecute cases in which police officers kill unarmed citizens, a possible model for national reform that could help restore the public's trust. As Schneiderman wrote in a letter to the governor, "A common thread in many of these cases is the belief of the victim's family and others that the investigation of the death, and the decision whether to prosecute, have been improperly and unfairly influenced by the close working relationship between the county District Attorney and the police officers he or she works with and depends on every day."

Indeed, we are now seeing a crisis of confidence in our justice system, which has left black communities in particular fearing that police can torment them with impunity. "This type of independent oversight is a critical first step in making sure officers who brutalize or kill Black New Yorkers are held accountable," the civil rights group ColorofChange.org said in a statement praising Schneiderman's request. "The relationship between police and district attorneys is far too close and AG Schneiderman's request would go a long way to avoid the systemic corruption, cronyism, and failed justice that often results when local prosecutors investigate police abuse involving Black victims."

New York City Public Advocate Letitia James said there is "an inherent bias in the judicial system in the relationship between police officers and district attorneys." In a recent MSNBC column, James argued, "Our justice system allows district attorneys to be charged with the great responsibility of prosecuting the very same police officers they work side-by-side with every day and whose union support they seek when running for reelection."

Former U.S. District Court Judge Paul Cassell, a George W. Bush appointee who defended the grand jury's decision in the Brown case, has suggested allowing state attorneys general to prosecute police misconduct for the same reason. "A district attorney's office that is one day calling a police officer to the stand as a critical witness may have a difficult time the next day investigating that same officer and charging him with a crime," he recently wrote in The Post.

The grand juries' decisions to not indict are especially shocking when you consider how unusual they were. In 2010, federal prosecutors failed to secure an indictment in just 11 out of 162,000 total cases, a success rate of 99.99 percent. Whatever the reason, it is clear that justice is not being served in cases of police brutality -- and the problem goes far beyond the recent headlines. The data on police shootings are incomplete, but the Federal Bureau of Investigation reported 2,718 justifiable homicides by law enforcement officials between 2005 and 2011. During that period, only 41 police officers faced murder or manslaughter charges for shootings that occurred while they were on duty, according to research out of Bowling State University. "The reason is because it's usually justified," said one police representative. But research also shows a bias toward the officers who do end up facing charges. Overall, criminal defendants in felony cases are convicted at roughly twice the rate -- and incarcerated at four times the rate -- as police officers charged with misconduct.

Schneiderman's proposal is a significant step that could serve as a model for the nation. It also demonstrates the importance of investing in state and local elections. For example, Republicans in the New York Senate look set to hold up criminal justice reform, with one prominent Republican insisting that "the system worked" in the Garner case.

At a time when there is political momentum to address mass incarceration and the war on drugs, it is crucial that our efforts to fix the broken criminal justice system include police reform. And while removing local district attorneys from the process of investigating police officers is a start, more can be done to repair relations between police and communities of color and protect people from bad policing, such as requiring officers to wear body cameras, defunding police departments that use excessive force or racial profiling, and ending the "broken windows" enforcement strategy that encourages aggressive interactions with low-level offenders.

As Dani McClain has written in the Nation, "This moment has the potential to catapult change." The recent tragedies have brought public attention to the pain and suffering that our criminal justice system has inflicted on black communities for decades. Now, with the protest movement growing, the cries for justice are getting louder every day. This moment, if met, could be the beginning of a renewed civil rights movement, one whose time has surely come.