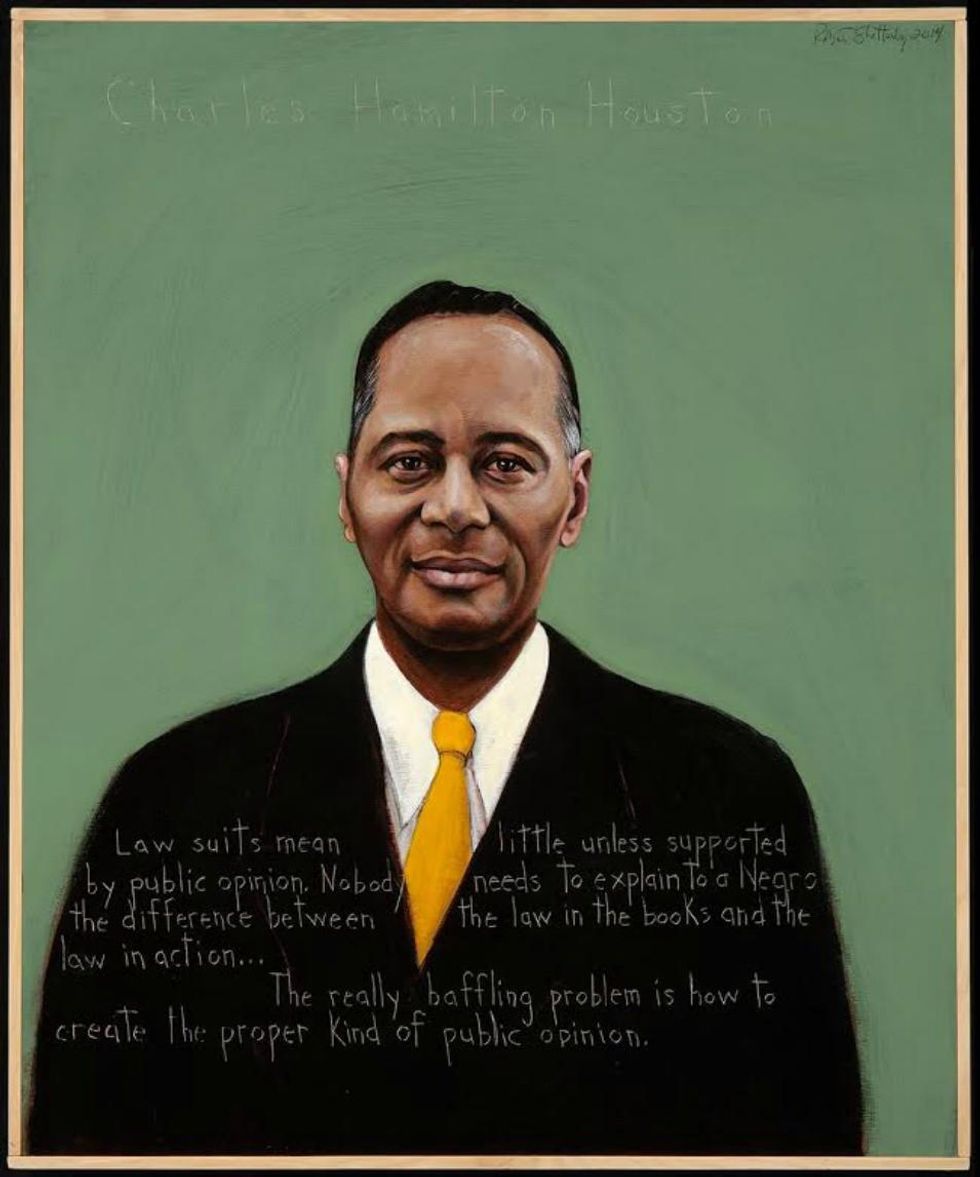

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time. This painting of Charles Hamilton Houston, an attorney and one of the key legal architects in the struggle for Civil Rights, is his latest portrait of those who dedicated their lives to equality, freedom and justice. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

For a number of years I have loved telling the story of Barbara Johns, the 16 year old Black girl who organized a walkout of her separate but very unequal school, Moton High, in Farmville, Virginia.

The year 1951 was a dangerous time for a young African American girl--or any Black person for that matter--to defy the racist structures of this country. All Johns demanded was that her school be separate and truly equal, knowing that a poor education would diminish her opportunities for success. I tell the story of the two Black lawyers from Richmond, VA, Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson III, who heard about the commotion in Farmville and went to meet Barbara and offered to take on her case. They convinced her that the correct demand, if she really wanted an equal education, was for integration of the school system.

Barbara's case remained in the courts for three years before Thurgood Marshall bundled it with four others and won the history-changing, 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, which determined that separate could only be unequal and was, therefore, unconstitutional. Reading Barbara's history, I had assumed that her courageous action was an historical anomaly and that the lawyers, Hill and Robinson, were too. I didn't know how wrong I was until my daughter-in-law Margot suggested I paint Charles Hamilton Houston. Who? I said.

Why is it that so many pivotal figures in our struggles to live up to our nation's common, professed ideals, are ignored in the history books? Until I was acquainted with Barbara Johns' story and painted her portrait, I had not heard of her. When I tell her story in classrooms, students always ask me why they are not taught about her. Why are courageous figures like Barbara not promoted as models for our kids? There is not one answer to that question, but the different answers are crucial to understanding the content and intention of our education system.

Charles Hamilton Houston was born in Washington, DC in 1895. He was the grandson of a slave, Thomas Jefferson Houston, who, after being badly beaten by his owner, escaped on a broken foot from Missouri into Illinois. When his foot healed, he became an important conductor on the Underground Railroad before later becoming a preacher. Thomas' son, and Charles' father, became a lawyer and ultimately encouraged his son to follow in his footsteps. Charles was reluctant. He was a talented pianist and good student who preferred not to have his life defined by his father's profession. At Amherst College he was the only Black student in his class--his exclusion there from many white activities afforded him lots of time to study. After college, as the U.S. in 1917 was about to enter WWI, Charles thought it his patriotic duty to enlist. He trained with a Black regiment--the US Army was segregated in this grand campaign to bring democracy to the world--and entered the war a captain of a Black artillery unit.

Charles had not expected that his most difficult and alarming experience in the war would be the racism he was subjected to by American soldiers and officers. At one point in France he was nearly lynched by white soldiers who had brought their Jim Crow prejudice across the ocean with them and were jealous of the attention French women paid to Black soldiers. Upon returning safely, he said, "The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. I made up my mind that if I got through this war I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back."

Charles enrolled in Harvard Law School, was the only African American in his class and the first to join the Harvard Law Review. A brilliant student, he was asked by his professors to remain at Harvard and get a doctor of laws degree. He also learned several languages and studied law in Madrid. Returning to Washington, he immediately took on civil rights cases. By the early 1930s, he realized that the best hope for racial justice in the US was an integrated educational system. He began devising a strategy for dismantling the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision that established "separate but equal" as constitutional. He said, "There is no such thing as separate but equal. Segregation itself imports inequality." And in 1935, he took his first challenge of Plessy to the Supreme Court. Houston argued that if a Black student wanted to go to graduate school and none existed for Black students, the state had to either establish a new graduate school or admit the student to the existing white school. The Supreme Court agreed with him. Many of his cases were based on the idea that states could mandate the separate, but to do so they would have to prove that the separate opportunity was truly equal. He believed that he would eventually force states to comply with integration because building equal, segregated institutions would be prohibitively expensive. He knew that public morality is often the stepchild of economics.

Working closely with his prize students from Howard University where he taught and also found time to create a fully accredited law school, Charles Hamilton Houston had, by 1950, won a whole series of cases that would pave the way to the final assault on segregated education. He was also head of the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund and was bringing other civil rights cases all over the US. Houston was being referred to as the man who killed Jim Crow. Tragically, also in 1950, Houston died of a heart attack at age 55. His students, who included Thurgood Marshall, Oliver Hill, and Spottswood Robinson III, carried his crusade forward.

What I had not realized when I was telling the story of Barbara Johns was that Charles Hamilton Houston''s students were scouring the country for strong cases to be part of a case like Brown v. Board. I had no idea that that case was 20 years in the making and was the final step of the brilliant legal strategy laid out by a tireless campaigner for racial justice. I had not realized there was a Black lawyer behind all this who said, "A lawyer is either a social engineer or he is a parasite on society." I had no idea that a man who did as much as anyone in the 20th Century to force civil rights progress was unknown to me. Why?

Monuments are built in Washington, DC for people who have insisted that this country close the bloody gap between its idealistic words and its hypocritical deeds. Of course there should be a monument for Lincoln and another for Dr. King. There should also be one for Charles Hamilton Houston.