Exposing Israel's 'Pinkwashing'

Pinkwashing is the word activists use to describe Israel's branding of itself as the gay oasis of the Middle East. It's a government-supported public relations strategy, they say, designed to help us all forget about Israel's occupation of Palestine.

These activists are part of a growing movement of anti-pinkwashers, committed to exposing Israel's pro-gay messaging as cynical propaganda, while at the same time bringing more attention to what many have labeled as Israeli apartheid.

"There's a really strong current all over the globe" of queer Palestinian human rights activism, said 26-year-old organizer Selma Al-Aswad. "It's a current that I didn't feel in my early days of organizing Palestine solidarity work. That was an isolated experience, and I do not feel that isolation anymore."

LGBTQ people in Palestine with groups like al-Qaws are actively trying to dispel the myth that Palestinian queers are interested in being "rescued" and integrated into Israeli society, and advocates for Palestinians around the world are forwarding the idea that gay tolerance, like allowing gays to openly serve in the country's conscripted military, doesn't excuse Israel's human rights violations. Meanwhile, in Israel's supposed gay mecca of Tel Aviv, violence against queer people persists.

A queer Palestinian American from Seattle, Al-Aswad remembers when she became aware of pinkwashing. It was the early 2000s, and she started seeing "certain messages popping up around gay culture in Israel, juxtaposing this vibrant queer community in Israel against the backdrop of bleakness in Palestine."

The most difficult to stomach, for her, are the messages that tell a certain narrative seen in the film The Invisible Men, which centers around conflicted love between gay Palestinians and Israelis. In the movie, Israel is depicted as a gay haven, while the West Bank is shown as being a dark, dangerous place for queer people. In the end, the invisible men of Palestine turn to Israel for salvation.

"The state of Israel actually saves queer Palestinians from their own kind," Al-Aswad said. "That's the hardest stuff to watch."

And so, in 2012, at the film's Seattle opening, Al-Aswad and her "fabulous queer crew, dressed in pink, with huge pink wigs, huge pink brushes," stormed the theater to bring attention to what they saw as the pinkwashing present in the movie. Similar actions took place when it premiered in San Francisco, Toronto and Vancouver.

June is Gay Pride month. For Natalie Kouri-Towe in Toronto this month brings an annual series of actions connecting queer struggles to the struggle in Palestine.

Today's Gay Pride celebrations have increasingly become another opportunity for big banks and liquor companies to advertise to gay consumers. For Kouri-Towe and others in Toronto's Queers Against Israeli Apartheid, or QuAIA, anti-pinkwashing activism is particularly meaningful because it's a chance to link Pride with its political origins. She points out how the original Pride march was actually a response to police violence against the gay community in New York City after the Stonewall riots in 1969. In Toronto, Pride marches formed in response to gay bathhouse raids during the 1980s, when, according to Kouri-Towe, "the cops raided the bathhouses, and the community took to the streets. None of that is part of [today's] Pride Parade."

QuAIA has tried many strategies over the years to bring more attention to the occupation. Several events have hailed the work of Simon Nkoli, a gay South African anti-apartheid activist who often linked queer and anti-apartheid struggles. (The chairperson of South Africa's post-apartheid ruling party, the African National Congress, called the current situation in Palestine "far worse than Apartheid South Africa.")

QuAIA has also denounced Israel's work to promote Tel Aviv as a gay vacation destination. As part of the boycott, divestment and sanctions, or BDS, movement, QuAIA marched in a recent Gay Pride parade, calling for a boycott of tourism in Israel.

Pitching QuAIA as a discriminatory, anti-Israel group, pro-Israeli lobbyists have pushed politicians to withhold public funding from LGBT organizations that allow QuAIA's participation.

Kouri-Towe's favorite anti-pinkwashing action happened during Toronto Pride 2011. Conservative mayor Rob Ford made it clear, she explained, "that he would ensure that Pride would not receive funding if QuAIA marched. So QuAIA said, 'We're not going to be used as the pretense for your homophobia. If you cut funding for the parade, that's all on you, because we're not going to be used as the platform you use to justify this." In response, the organization decided not to march.

"We were really nervous about that move," she said. "The response we got back was that it was a really good gesture of mutual responsibility around solidarity, and we still did a big event that year, with a banner drop in the Village in front of the subway that's right next to the Parade." The move received significant press coverage and increased QuAIA's numbers.

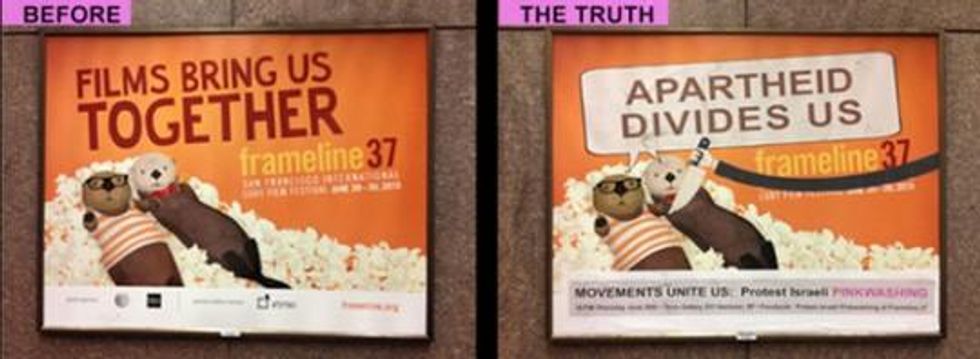

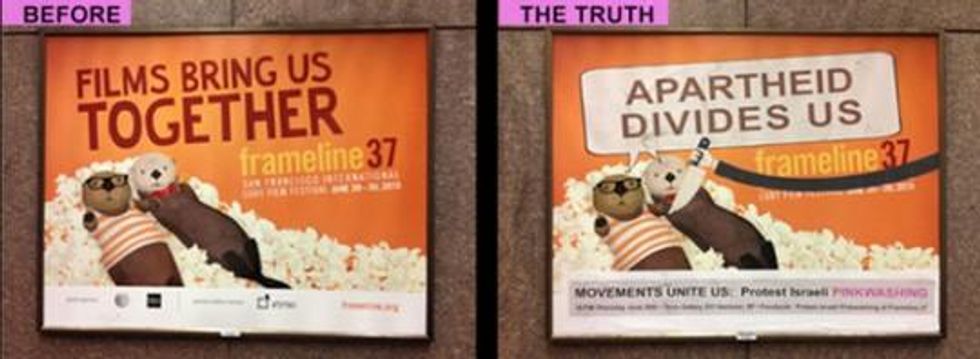

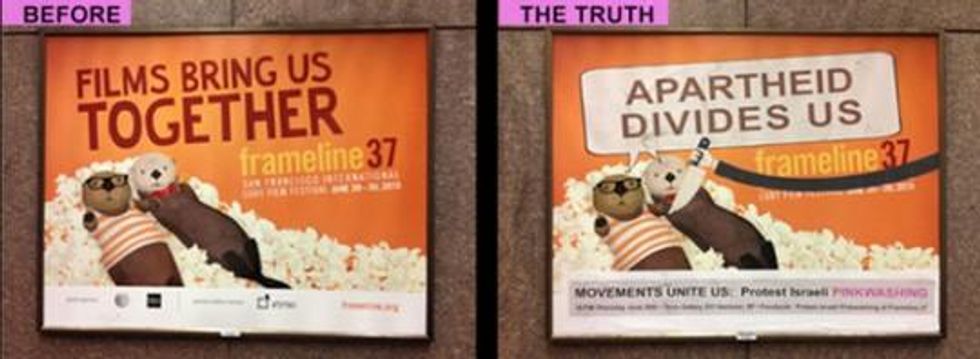

Another well-known gay event held every June is the Frameline LGBT film festival in San Francisco. Advertising itself as the largest and longest-running LGBT cultural event in the world, the festival is sponsored in part by the Israeli consulate. A growing list of artists and filmmakers -- including John Greyson, who was famously detained in Egypt for several months last year, author Alice Walker and former political prisoner Angela Davis -- have either pulled their films or called for "discontinuing its financial relationship with the state of Israel." So far, however, the festival's leadership has refused to cut ties with the consulate. (In 2011, leaked emails revealed a collaborative effort between Frameline, the Israeli consulate and programs within the Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco to thwart protests.)

Kate Raphael has been organizing against pinkwashing as part of the majority-Jewish group Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism in San Francisco since the early 2000s. In May, the group picketed Frameline's press briefing.

"It infuriates me that they're allowing our identity to be co-opted," she said. "I don't know any other way to say it than if someone is going to speak in your name, and what they say is abhorrent to you, you just have no choice [but to fight back]."

In another action, Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism pulled all of the Israel-produced items off the shelves of a Trader Joe's market.

"We don't worry so much about being transparent all the time -- some people would say we try to be really opaque!" Raphael said. "But we feel that if people don't understand something right away, that's not such a bad thing." The creative actions, she explained, "are just more fun for us," and they combat member burnout.

"There are times when things get a life on the Internet because they're flashy and interesting," Raphael continued. An early BDS action she helped to plan that involved occupying a Starbucks in Berkeley, Calif., was soon replicated in places as far away as Beirut and Sydney.

At the same time, Raphael -- who was once arrested and deported from Israel after filming clashes between Palestinians and the Israeli military -- believes consistency is key to getting the movement to where it is today.

"If we want Target to stop selling Soda Stream [a carbonated beverage maker made by an Israeli company that produces many of its products in the West Bank], we have to be out there [protesting] every week," she said. "You can't just have one flashy action every few months and expect to have an impact."

One of the most effective anti-pinkwashing actions took place during the spring in 2012, in response to a West Coast tour by pro-Israel organizations A Wider Bridge and StandWithUs. It featured several Israeli gay rights activists with funding from the Israeli consulate.

"There were events that were going to be held in Olympia and Tacoma," said Al-Aswad. "But the most prominent event was going to be held in Seattle, and it was going to be hosted by the Seattle LGBT Commission [which advises Seattle's mayor on LGBT issues at City Hall]."

Al-Aswad and two other queer Palestinians went to the meeting, and got up in front of the commissioners to tell their story. "The really beautiful thing that happened is that people actually heard," she said.

After listening to Al-Aswad and the others talk about the injustices in Palestine, the commissioners were visibly upset; some were even crying. "It was this incredibly unprecedented event," Al-Aswad said. "They voted to cancel this major city-sponsored event."

There was backlash. Several major Seattle LGBT organizations -- including, according to Al-Aswad, those that run the queer and trans film festival, HIV outreach organizations and several that provide community mental health support -- were pressured to sign a letter criticizing the LGBT Commission's decision and calling for an independent review.

According to Al-Aswad, while the fallout "really compromised the trust that queer people of Seattle had for these organizations, it also created an opportunity to address racism, and misunderstanding about Palestine in the LGBT context. Several people from our community actually joined the Commission after the organizing." Al-Aswad was later invited to share the experience with attendees of the World Social Forum in Brazil, and the success of the action led to the creation of Queers Against Israeli Apartheid in Seattle.

"By the time we had our first Seattle QuAIA meeting there was a regular group of about 50 people showing up," said Dean Spade, a Seattle organizer who is currently working on a film about the action. "In addition, the other long-standing groups of Palestine solidarity activists in the region, including Jewish Voices for Peace and others, have all remained involved with and supportive of anti-pinkwashing work in Seattle."

After many years of organizing, mainstream media like The New York Times have run articles on pinkwashing, bringing the concept to a mainstream audience. A widely publicized academic conference on pinkwashing was held in New York City last year. Israel's publicity blitz continues, though, particularly with respect to gay tourism; its Gay Tel Aviv campaign launched with a huge government investment of close to $90 million four years ago.

"In a lot of ways I think that Israel's use of pinkwashing, and really trying to get at this niche community, if you will, speaks to the success [of anti-pinkwashing activism]," Al-Aswad said with hope and excitement in her voice. "This is happening all over. It shows you how threatened the powers that be are with losing legitimacy, and losing support."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Pinkwashing is the word activists use to describe Israel's branding of itself as the gay oasis of the Middle East. It's a government-supported public relations strategy, they say, designed to help us all forget about Israel's occupation of Palestine.

These activists are part of a growing movement of anti-pinkwashers, committed to exposing Israel's pro-gay messaging as cynical propaganda, while at the same time bringing more attention to what many have labeled as Israeli apartheid.

"There's a really strong current all over the globe" of queer Palestinian human rights activism, said 26-year-old organizer Selma Al-Aswad. "It's a current that I didn't feel in my early days of organizing Palestine solidarity work. That was an isolated experience, and I do not feel that isolation anymore."

LGBTQ people in Palestine with groups like al-Qaws are actively trying to dispel the myth that Palestinian queers are interested in being "rescued" and integrated into Israeli society, and advocates for Palestinians around the world are forwarding the idea that gay tolerance, like allowing gays to openly serve in the country's conscripted military, doesn't excuse Israel's human rights violations. Meanwhile, in Israel's supposed gay mecca of Tel Aviv, violence against queer people persists.

A queer Palestinian American from Seattle, Al-Aswad remembers when she became aware of pinkwashing. It was the early 2000s, and she started seeing "certain messages popping up around gay culture in Israel, juxtaposing this vibrant queer community in Israel against the backdrop of bleakness in Palestine."

The most difficult to stomach, for her, are the messages that tell a certain narrative seen in the film The Invisible Men, which centers around conflicted love between gay Palestinians and Israelis. In the movie, Israel is depicted as a gay haven, while the West Bank is shown as being a dark, dangerous place for queer people. In the end, the invisible men of Palestine turn to Israel for salvation.

"The state of Israel actually saves queer Palestinians from their own kind," Al-Aswad said. "That's the hardest stuff to watch."

And so, in 2012, at the film's Seattle opening, Al-Aswad and her "fabulous queer crew, dressed in pink, with huge pink wigs, huge pink brushes," stormed the theater to bring attention to what they saw as the pinkwashing present in the movie. Similar actions took place when it premiered in San Francisco, Toronto and Vancouver.

June is Gay Pride month. For Natalie Kouri-Towe in Toronto this month brings an annual series of actions connecting queer struggles to the struggle in Palestine.

Today's Gay Pride celebrations have increasingly become another opportunity for big banks and liquor companies to advertise to gay consumers. For Kouri-Towe and others in Toronto's Queers Against Israeli Apartheid, or QuAIA, anti-pinkwashing activism is particularly meaningful because it's a chance to link Pride with its political origins. She points out how the original Pride march was actually a response to police violence against the gay community in New York City after the Stonewall riots in 1969. In Toronto, Pride marches formed in response to gay bathhouse raids during the 1980s, when, according to Kouri-Towe, "the cops raided the bathhouses, and the community took to the streets. None of that is part of [today's] Pride Parade."

QuAIA has tried many strategies over the years to bring more attention to the occupation. Several events have hailed the work of Simon Nkoli, a gay South African anti-apartheid activist who often linked queer and anti-apartheid struggles. (The chairperson of South Africa's post-apartheid ruling party, the African National Congress, called the current situation in Palestine "far worse than Apartheid South Africa.")

QuAIA has also denounced Israel's work to promote Tel Aviv as a gay vacation destination. As part of the boycott, divestment and sanctions, or BDS, movement, QuAIA marched in a recent Gay Pride parade, calling for a boycott of tourism in Israel.

Pitching QuAIA as a discriminatory, anti-Israel group, pro-Israeli lobbyists have pushed politicians to withhold public funding from LGBT organizations that allow QuAIA's participation.

Kouri-Towe's favorite anti-pinkwashing action happened during Toronto Pride 2011. Conservative mayor Rob Ford made it clear, she explained, "that he would ensure that Pride would not receive funding if QuAIA marched. So QuAIA said, 'We're not going to be used as the pretense for your homophobia. If you cut funding for the parade, that's all on you, because we're not going to be used as the platform you use to justify this." In response, the organization decided not to march.

"We were really nervous about that move," she said. "The response we got back was that it was a really good gesture of mutual responsibility around solidarity, and we still did a big event that year, with a banner drop in the Village in front of the subway that's right next to the Parade." The move received significant press coverage and increased QuAIA's numbers.

Another well-known gay event held every June is the Frameline LGBT film festival in San Francisco. Advertising itself as the largest and longest-running LGBT cultural event in the world, the festival is sponsored in part by the Israeli consulate. A growing list of artists and filmmakers -- including John Greyson, who was famously detained in Egypt for several months last year, author Alice Walker and former political prisoner Angela Davis -- have either pulled their films or called for "discontinuing its financial relationship with the state of Israel." So far, however, the festival's leadership has refused to cut ties with the consulate. (In 2011, leaked emails revealed a collaborative effort between Frameline, the Israeli consulate and programs within the Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco to thwart protests.)

Kate Raphael has been organizing against pinkwashing as part of the majority-Jewish group Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism in San Francisco since the early 2000s. In May, the group picketed Frameline's press briefing.

"It infuriates me that they're allowing our identity to be co-opted," she said. "I don't know any other way to say it than if someone is going to speak in your name, and what they say is abhorrent to you, you just have no choice [but to fight back]."

In another action, Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism pulled all of the Israel-produced items off the shelves of a Trader Joe's market.

"We don't worry so much about being transparent all the time -- some people would say we try to be really opaque!" Raphael said. "But we feel that if people don't understand something right away, that's not such a bad thing." The creative actions, she explained, "are just more fun for us," and they combat member burnout.

"There are times when things get a life on the Internet because they're flashy and interesting," Raphael continued. An early BDS action she helped to plan that involved occupying a Starbucks in Berkeley, Calif., was soon replicated in places as far away as Beirut and Sydney.

At the same time, Raphael -- who was once arrested and deported from Israel after filming clashes between Palestinians and the Israeli military -- believes consistency is key to getting the movement to where it is today.

"If we want Target to stop selling Soda Stream [a carbonated beverage maker made by an Israeli company that produces many of its products in the West Bank], we have to be out there [protesting] every week," she said. "You can't just have one flashy action every few months and expect to have an impact."

One of the most effective anti-pinkwashing actions took place during the spring in 2012, in response to a West Coast tour by pro-Israel organizations A Wider Bridge and StandWithUs. It featured several Israeli gay rights activists with funding from the Israeli consulate.

"There were events that were going to be held in Olympia and Tacoma," said Al-Aswad. "But the most prominent event was going to be held in Seattle, and it was going to be hosted by the Seattle LGBT Commission [which advises Seattle's mayor on LGBT issues at City Hall]."

Al-Aswad and two other queer Palestinians went to the meeting, and got up in front of the commissioners to tell their story. "The really beautiful thing that happened is that people actually heard," she said.

After listening to Al-Aswad and the others talk about the injustices in Palestine, the commissioners were visibly upset; some were even crying. "It was this incredibly unprecedented event," Al-Aswad said. "They voted to cancel this major city-sponsored event."

There was backlash. Several major Seattle LGBT organizations -- including, according to Al-Aswad, those that run the queer and trans film festival, HIV outreach organizations and several that provide community mental health support -- were pressured to sign a letter criticizing the LGBT Commission's decision and calling for an independent review.

According to Al-Aswad, while the fallout "really compromised the trust that queer people of Seattle had for these organizations, it also created an opportunity to address racism, and misunderstanding about Palestine in the LGBT context. Several people from our community actually joined the Commission after the organizing." Al-Aswad was later invited to share the experience with attendees of the World Social Forum in Brazil, and the success of the action led to the creation of Queers Against Israeli Apartheid in Seattle.

"By the time we had our first Seattle QuAIA meeting there was a regular group of about 50 people showing up," said Dean Spade, a Seattle organizer who is currently working on a film about the action. "In addition, the other long-standing groups of Palestine solidarity activists in the region, including Jewish Voices for Peace and others, have all remained involved with and supportive of anti-pinkwashing work in Seattle."

After many years of organizing, mainstream media like The New York Times have run articles on pinkwashing, bringing the concept to a mainstream audience. A widely publicized academic conference on pinkwashing was held in New York City last year. Israel's publicity blitz continues, though, particularly with respect to gay tourism; its Gay Tel Aviv campaign launched with a huge government investment of close to $90 million four years ago.

"In a lot of ways I think that Israel's use of pinkwashing, and really trying to get at this niche community, if you will, speaks to the success [of anti-pinkwashing activism]," Al-Aswad said with hope and excitement in her voice. "This is happening all over. It shows you how threatened the powers that be are with losing legitimacy, and losing support."

Pinkwashing is the word activists use to describe Israel's branding of itself as the gay oasis of the Middle East. It's a government-supported public relations strategy, they say, designed to help us all forget about Israel's occupation of Palestine.

These activists are part of a growing movement of anti-pinkwashers, committed to exposing Israel's pro-gay messaging as cynical propaganda, while at the same time bringing more attention to what many have labeled as Israeli apartheid.

"There's a really strong current all over the globe" of queer Palestinian human rights activism, said 26-year-old organizer Selma Al-Aswad. "It's a current that I didn't feel in my early days of organizing Palestine solidarity work. That was an isolated experience, and I do not feel that isolation anymore."

LGBTQ people in Palestine with groups like al-Qaws are actively trying to dispel the myth that Palestinian queers are interested in being "rescued" and integrated into Israeli society, and advocates for Palestinians around the world are forwarding the idea that gay tolerance, like allowing gays to openly serve in the country's conscripted military, doesn't excuse Israel's human rights violations. Meanwhile, in Israel's supposed gay mecca of Tel Aviv, violence against queer people persists.

A queer Palestinian American from Seattle, Al-Aswad remembers when she became aware of pinkwashing. It was the early 2000s, and she started seeing "certain messages popping up around gay culture in Israel, juxtaposing this vibrant queer community in Israel against the backdrop of bleakness in Palestine."

The most difficult to stomach, for her, are the messages that tell a certain narrative seen in the film The Invisible Men, which centers around conflicted love between gay Palestinians and Israelis. In the movie, Israel is depicted as a gay haven, while the West Bank is shown as being a dark, dangerous place for queer people. In the end, the invisible men of Palestine turn to Israel for salvation.

"The state of Israel actually saves queer Palestinians from their own kind," Al-Aswad said. "That's the hardest stuff to watch."

And so, in 2012, at the film's Seattle opening, Al-Aswad and her "fabulous queer crew, dressed in pink, with huge pink wigs, huge pink brushes," stormed the theater to bring attention to what they saw as the pinkwashing present in the movie. Similar actions took place when it premiered in San Francisco, Toronto and Vancouver.

June is Gay Pride month. For Natalie Kouri-Towe in Toronto this month brings an annual series of actions connecting queer struggles to the struggle in Palestine.

Today's Gay Pride celebrations have increasingly become another opportunity for big banks and liquor companies to advertise to gay consumers. For Kouri-Towe and others in Toronto's Queers Against Israeli Apartheid, or QuAIA, anti-pinkwashing activism is particularly meaningful because it's a chance to link Pride with its political origins. She points out how the original Pride march was actually a response to police violence against the gay community in New York City after the Stonewall riots in 1969. In Toronto, Pride marches formed in response to gay bathhouse raids during the 1980s, when, according to Kouri-Towe, "the cops raided the bathhouses, and the community took to the streets. None of that is part of [today's] Pride Parade."

QuAIA has tried many strategies over the years to bring more attention to the occupation. Several events have hailed the work of Simon Nkoli, a gay South African anti-apartheid activist who often linked queer and anti-apartheid struggles. (The chairperson of South Africa's post-apartheid ruling party, the African National Congress, called the current situation in Palestine "far worse than Apartheid South Africa.")

QuAIA has also denounced Israel's work to promote Tel Aviv as a gay vacation destination. As part of the boycott, divestment and sanctions, or BDS, movement, QuAIA marched in a recent Gay Pride parade, calling for a boycott of tourism in Israel.

Pitching QuAIA as a discriminatory, anti-Israel group, pro-Israeli lobbyists have pushed politicians to withhold public funding from LGBT organizations that allow QuAIA's participation.

Kouri-Towe's favorite anti-pinkwashing action happened during Toronto Pride 2011. Conservative mayor Rob Ford made it clear, she explained, "that he would ensure that Pride would not receive funding if QuAIA marched. So QuAIA said, 'We're not going to be used as the pretense for your homophobia. If you cut funding for the parade, that's all on you, because we're not going to be used as the platform you use to justify this." In response, the organization decided not to march.

"We were really nervous about that move," she said. "The response we got back was that it was a really good gesture of mutual responsibility around solidarity, and we still did a big event that year, with a banner drop in the Village in front of the subway that's right next to the Parade." The move received significant press coverage and increased QuAIA's numbers.

Another well-known gay event held every June is the Frameline LGBT film festival in San Francisco. Advertising itself as the largest and longest-running LGBT cultural event in the world, the festival is sponsored in part by the Israeli consulate. A growing list of artists and filmmakers -- including John Greyson, who was famously detained in Egypt for several months last year, author Alice Walker and former political prisoner Angela Davis -- have either pulled their films or called for "discontinuing its financial relationship with the state of Israel." So far, however, the festival's leadership has refused to cut ties with the consulate. (In 2011, leaked emails revealed a collaborative effort between Frameline, the Israeli consulate and programs within the Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco to thwart protests.)

Kate Raphael has been organizing against pinkwashing as part of the majority-Jewish group Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism in San Francisco since the early 2000s. In May, the group picketed Frameline's press briefing.

"It infuriates me that they're allowing our identity to be co-opted," she said. "I don't know any other way to say it than if someone is going to speak in your name, and what they say is abhorrent to you, you just have no choice [but to fight back]."

In another action, Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism pulled all of the Israel-produced items off the shelves of a Trader Joe's market.

"We don't worry so much about being transparent all the time -- some people would say we try to be really opaque!" Raphael said. "But we feel that if people don't understand something right away, that's not such a bad thing." The creative actions, she explained, "are just more fun for us," and they combat member burnout.

"There are times when things get a life on the Internet because they're flashy and interesting," Raphael continued. An early BDS action she helped to plan that involved occupying a Starbucks in Berkeley, Calif., was soon replicated in places as far away as Beirut and Sydney.

At the same time, Raphael -- who was once arrested and deported from Israel after filming clashes between Palestinians and the Israeli military -- believes consistency is key to getting the movement to where it is today.

"If we want Target to stop selling Soda Stream [a carbonated beverage maker made by an Israeli company that produces many of its products in the West Bank], we have to be out there [protesting] every week," she said. "You can't just have one flashy action every few months and expect to have an impact."

One of the most effective anti-pinkwashing actions took place during the spring in 2012, in response to a West Coast tour by pro-Israel organizations A Wider Bridge and StandWithUs. It featured several Israeli gay rights activists with funding from the Israeli consulate.

"There were events that were going to be held in Olympia and Tacoma," said Al-Aswad. "But the most prominent event was going to be held in Seattle, and it was going to be hosted by the Seattle LGBT Commission [which advises Seattle's mayor on LGBT issues at City Hall]."

Al-Aswad and two other queer Palestinians went to the meeting, and got up in front of the commissioners to tell their story. "The really beautiful thing that happened is that people actually heard," she said.

After listening to Al-Aswad and the others talk about the injustices in Palestine, the commissioners were visibly upset; some were even crying. "It was this incredibly unprecedented event," Al-Aswad said. "They voted to cancel this major city-sponsored event."

There was backlash. Several major Seattle LGBT organizations -- including, according to Al-Aswad, those that run the queer and trans film festival, HIV outreach organizations and several that provide community mental health support -- were pressured to sign a letter criticizing the LGBT Commission's decision and calling for an independent review.

According to Al-Aswad, while the fallout "really compromised the trust that queer people of Seattle had for these organizations, it also created an opportunity to address racism, and misunderstanding about Palestine in the LGBT context. Several people from our community actually joined the Commission after the organizing." Al-Aswad was later invited to share the experience with attendees of the World Social Forum in Brazil, and the success of the action led to the creation of Queers Against Israeli Apartheid in Seattle.

"By the time we had our first Seattle QuAIA meeting there was a regular group of about 50 people showing up," said Dean Spade, a Seattle organizer who is currently working on a film about the action. "In addition, the other long-standing groups of Palestine solidarity activists in the region, including Jewish Voices for Peace and others, have all remained involved with and supportive of anti-pinkwashing work in Seattle."

After many years of organizing, mainstream media like The New York Times have run articles on pinkwashing, bringing the concept to a mainstream audience. A widely publicized academic conference on pinkwashing was held in New York City last year. Israel's publicity blitz continues, though, particularly with respect to gay tourism; its Gay Tel Aviv campaign launched with a huge government investment of close to $90 million four years ago.

"In a lot of ways I think that Israel's use of pinkwashing, and really trying to get at this niche community, if you will, speaks to the success [of anti-pinkwashing activism]," Al-Aswad said with hope and excitement in her voice. "This is happening all over. It shows you how threatened the powers that be are with losing legitimacy, and losing support."