This Island Earth

For those of us of a certain age, it seems as if the world has always been ending. It's easy now to forget just how deep fears and fantasies about a nuclear apocalypse went in the "golden" 1950s. And I'm not just thinking about kids like me "

No one was immune from such experiences and fears. In June 1953, for instance, President Dwight Eisenhower screened Operation IVY, a top-secret film about the first successful full-scale test of an H-bomb at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands. That bomb was not just a city-killer, but also a potential civilization destroyer. The screening took place at the White House with the full cabinet and the Joint Chiefs in attendance. The president was evidently deeply disturbed by the image of an "entire atoll" vanishing "into a crater" and, adds Weart, by "the fireball with a dwarfed New York City skyline printed across it in black silhouette." In 1956, Democratic presidential candidate Estes Kefauver announced that H-bombs could "right now blow the earth off its axis by 16 degrees." Talk about waking nightmares.

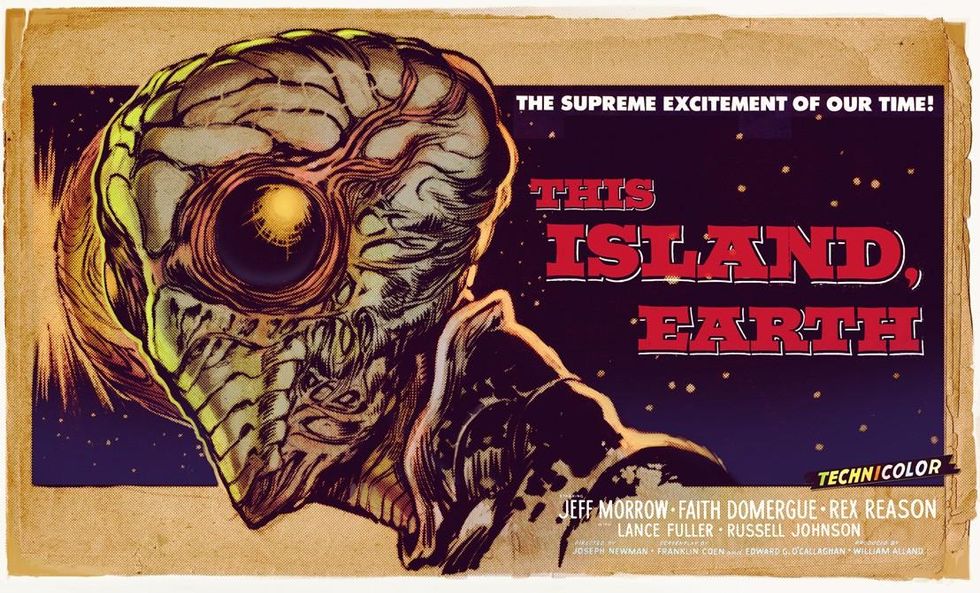

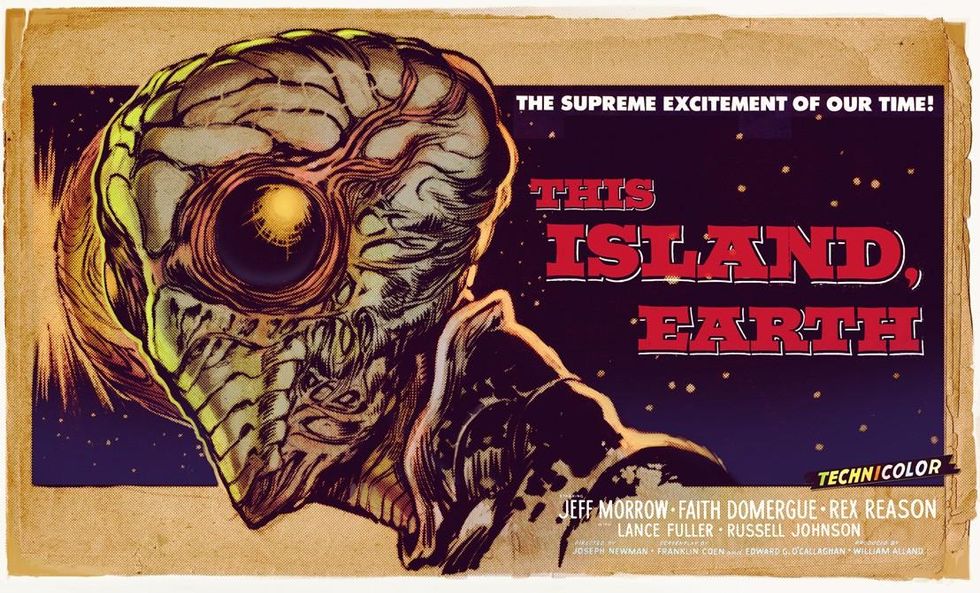

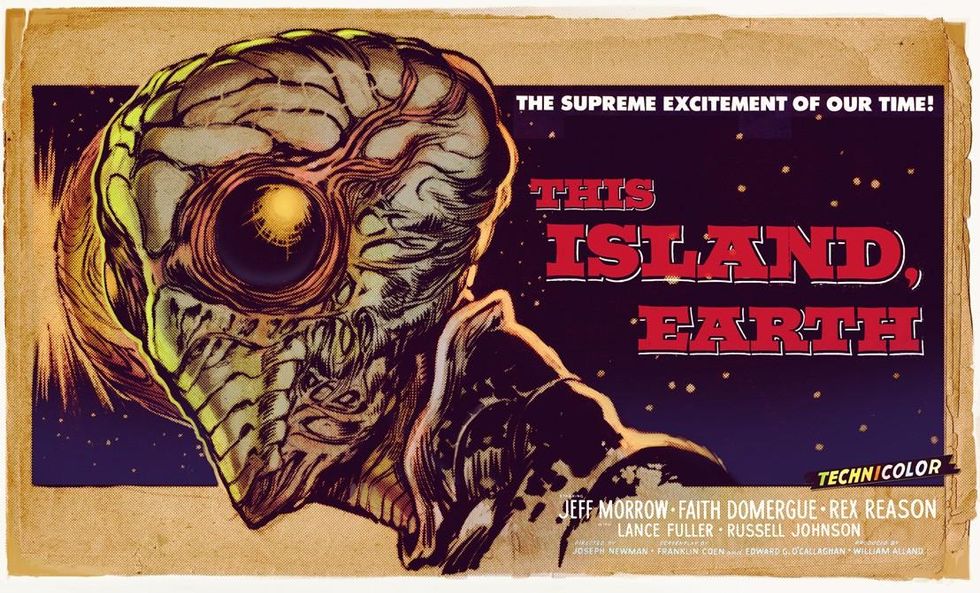

In the same years, if you happened to be young and at the movies, nuclearized America was taking vivid shape. In the Arctic, the first radioactivated monster, Ray Bradbury's Rhedosaurus, awakened in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms to begin its long slouch toward New York City; in the Southwestern desert, near the Trinity testing grounds for the first atomic bomb, a giant mutated queen ant in Them! prepared for her long flight to the sewers of Los Angeles to spawn; in space, the planet Metaluna displayed "the consequences of a weak defense system" by being incinerated in This Island Earth. And don't forget the return of the irrepressible, the A-bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1954, Godzilla, that reptilian nightmare "awakened" by atomic tests, stomped out of Japan's Toho studios to barnstorm through American theaters.

No wonder that, of all my thousands of dreams from those years, no matter how vivid or fantastic, the only ones I remember are those in which I seemed to experience "the Bomb" going off, saw the mushroom cloud rising, or found myself crawling through the rubble of atomically obliterated cities. In this, I suspect, I'm not alone in my generation. In fact, I've always had the desire to conduct a little informal survey, collecting the atomic dreamscapes of my peers from that era. If I had another life, I undoubtedly would.

From the actual nuclear destruction of 1945 to the prospective nuclear destruction that, in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, seemed briefly to reach the edge of a world-ending boil, to the possibility today of a global "nuclear winter" set off by a regional war between India and Pakistan, who knows just how the fear of a nuclear apocalypse has embedded itself in consciousness. All we can know is that it has, and that a climate-change version of the same, perhaps even harder to grasp and absorb, has been creeping into our imaginations and dreamscapes in recent years. Religious scholar and historian Ira Chernus catches the essence of this moment, taking the deep plunge into the modern version of the apocalyptic imagination in his "What Ever Happened to Plain Old Apocalypse." He wonders whether the crater the first H-bomb left in Eniwetok Atoll is where hope lies buried.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

No one was immune from such experiences and fears. In June 1953, for instance, President Dwight Eisenhower screened Operation IVY, a top-secret film about the first successful full-scale test of an H-bomb at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands. That bomb was not just a city-killer, but also a potential civilization destroyer. The screening took place at the White House with the full cabinet and the Joint Chiefs in attendance. The president was evidently deeply disturbed by the image of an "entire atoll" vanishing "into a crater" and, adds Weart, by "the fireball with a dwarfed New York City skyline printed across it in black silhouette." In 1956, Democratic presidential candidate Estes Kefauver announced that H-bombs could "right now blow the earth off its axis by 16 degrees." Talk about waking nightmares.

In the same years, if you happened to be young and at the movies, nuclearized America was taking vivid shape. In the Arctic, the first radioactivated monster, Ray Bradbury's Rhedosaurus, awakened in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms to begin its long slouch toward New York City; in the Southwestern desert, near the Trinity testing grounds for the first atomic bomb, a giant mutated queen ant in Them! prepared for her long flight to the sewers of Los Angeles to spawn; in space, the planet Metaluna displayed "the consequences of a weak defense system" by being incinerated in This Island Earth. And don't forget the return of the irrepressible, the A-bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1954, Godzilla, that reptilian nightmare "awakened" by atomic tests, stomped out of Japan's Toho studios to barnstorm through American theaters.

No wonder that, of all my thousands of dreams from those years, no matter how vivid or fantastic, the only ones I remember are those in which I seemed to experience "the Bomb" going off, saw the mushroom cloud rising, or found myself crawling through the rubble of atomically obliterated cities. In this, I suspect, I'm not alone in my generation. In fact, I've always had the desire to conduct a little informal survey, collecting the atomic dreamscapes of my peers from that era. If I had another life, I undoubtedly would.

From the actual nuclear destruction of 1945 to the prospective nuclear destruction that, in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, seemed briefly to reach the edge of a world-ending boil, to the possibility today of a global "nuclear winter" set off by a regional war between India and Pakistan, who knows just how the fear of a nuclear apocalypse has embedded itself in consciousness. All we can know is that it has, and that a climate-change version of the same, perhaps even harder to grasp and absorb, has been creeping into our imaginations and dreamscapes in recent years. Religious scholar and historian Ira Chernus catches the essence of this moment, taking the deep plunge into the modern version of the apocalyptic imagination in his "What Ever Happened to Plain Old Apocalypse." He wonders whether the crater the first H-bomb left in Eniwetok Atoll is where hope lies buried.

No one was immune from such experiences and fears. In June 1953, for instance, President Dwight Eisenhower screened Operation IVY, a top-secret film about the first successful full-scale test of an H-bomb at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands. That bomb was not just a city-killer, but also a potential civilization destroyer. The screening took place at the White House with the full cabinet and the Joint Chiefs in attendance. The president was evidently deeply disturbed by the image of an "entire atoll" vanishing "into a crater" and, adds Weart, by "the fireball with a dwarfed New York City skyline printed across it in black silhouette." In 1956, Democratic presidential candidate Estes Kefauver announced that H-bombs could "right now blow the earth off its axis by 16 degrees." Talk about waking nightmares.

In the same years, if you happened to be young and at the movies, nuclearized America was taking vivid shape. In the Arctic, the first radioactivated monster, Ray Bradbury's Rhedosaurus, awakened in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms to begin its long slouch toward New York City; in the Southwestern desert, near the Trinity testing grounds for the first atomic bomb, a giant mutated queen ant in Them! prepared for her long flight to the sewers of Los Angeles to spawn; in space, the planet Metaluna displayed "the consequences of a weak defense system" by being incinerated in This Island Earth. And don't forget the return of the irrepressible, the A-bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1954, Godzilla, that reptilian nightmare "awakened" by atomic tests, stomped out of Japan's Toho studios to barnstorm through American theaters.

No wonder that, of all my thousands of dreams from those years, no matter how vivid or fantastic, the only ones I remember are those in which I seemed to experience "the Bomb" going off, saw the mushroom cloud rising, or found myself crawling through the rubble of atomically obliterated cities. In this, I suspect, I'm not alone in my generation. In fact, I've always had the desire to conduct a little informal survey, collecting the atomic dreamscapes of my peers from that era. If I had another life, I undoubtedly would.

From the actual nuclear destruction of 1945 to the prospective nuclear destruction that, in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, seemed briefly to reach the edge of a world-ending boil, to the possibility today of a global "nuclear winter" set off by a regional war between India and Pakistan, who knows just how the fear of a nuclear apocalypse has embedded itself in consciousness. All we can know is that it has, and that a climate-change version of the same, perhaps even harder to grasp and absorb, has been creeping into our imaginations and dreamscapes in recent years. Religious scholar and historian Ira Chernus catches the essence of this moment, taking the deep plunge into the modern version of the apocalyptic imagination in his "What Ever Happened to Plain Old Apocalypse." He wonders whether the crater the first H-bomb left in Eniwetok Atoll is where hope lies buried.