SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

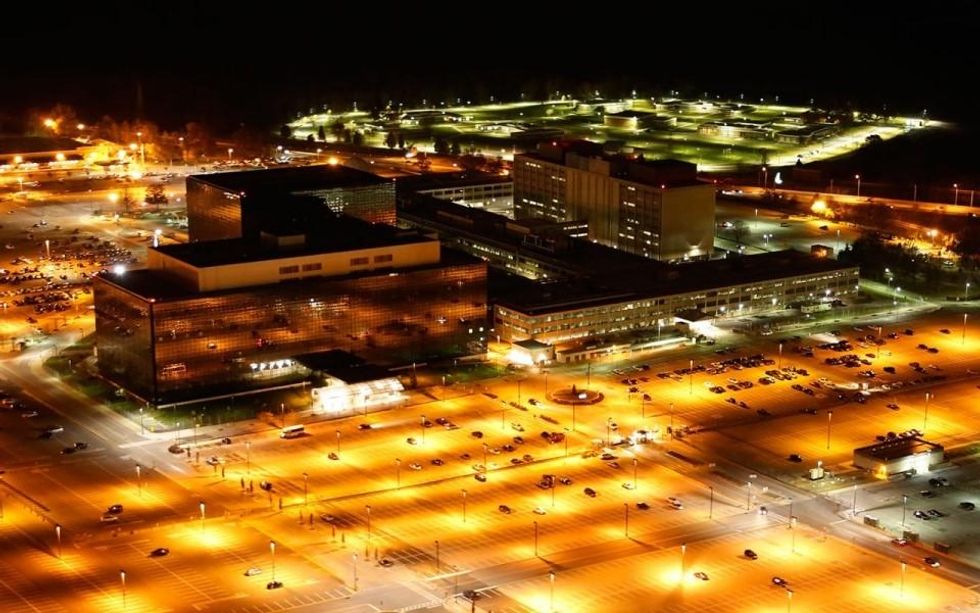

The mind-boggling scope of the NSA's surveillance continues to make front-page news as a political story. But its most pernicious effects are social and psychological. We are getting accustomed to Big Brother. Our daily lives are now accessible to prying eyes and ears no farther away than the nearest computer or cellphone. Unless we directly challenge the system of mass surveillance now, the ruling elites may understand our complacency as consent, with results that extend the reach of surveillance and its damaging consequences. Even as it grows more familiar, this bulk collection of data is corroding civil society.

Mass surveillance amounts to a siege that subtly constrains our freedoms and injures social relations. Freewheeling civic engagement is in the line of fire. The surveillance state generates fearful conformity.

To resist the growing possibility of this mind-set, Feb. 11 was designated The Day We Fight Back, with more than 5,300 nonprofit groups and private companies joining forces to demand an end to the numbing tyranny of mass surveillance.

Where does this resolute anger come from? The widespread public discontent seeks to reject the myriad ways the NSA's spying has undermined and continues to undermine our common humanity.

The NSA's partnership with the cutting-edge tech sector has given immense power to the government and gigantic profits to private firms. It is an ongoing collaboration that makes a digital mockery of the Fourth Amendment commitment to "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects."

By closely monitoring those it claims to respect and protect, the U.S. government is doing enormous and cumulative damage. In realms that stretch from public to intimate, people are growing acutely aware that much of what they say and do is becoming officially retrievable -- and might be used against them, someday, somehow.

Whether engaged in a phone discussion, email correspondence, online searches, banter at a party or even a quiet conversation at home, people are losing a sense of activity that is truly private. The omniscience wielded by authorities is crowding into the most human of spaces, casting an ominous shadow over free communication and boosting inclinations to self-censor.

The mistrust and cynicism due to regular surveillance only gets worse as top officials resort to mendacity to defend it. "We don't have a domestic spying program," President Barack Obama declared on "The Tonight Show" in early August, two months after the NSA scandal broke. He insisted, "There is no spying on Americans."

This lying became part of a whole dissembling repertoire. Five months later, in his much ballyhooed Jan. 17 speech about the NSA, Obama was still in deception mode, proclaiming, "The bottom line is that people around the world, regardless of their nationality, should know that the United States is not spying on ordinary people who don't threaten our national security."

But NSA documents provided by Snowden make clear that the U.S. government is spying on ordinary people every day -- on a humongous scale.

Along the way, surveillance has played a key role in the government's moves against whistle-blowers and journalists. In September the Obama administration proudly announced a long prison sentence for a former FBI agent who was tripped up by the Department of Justice's secret seizure of call records for 20 phone lines used by Associated Press reporters and editors. To all but the most pliant journalists, this trend is ominous and already destructive.

Even the media establishment is sounding the alarm. The Committee to Protect Journalists, a blue-ribbon press-freedom watchdog, issued an extraordinary report on Oct. 10, "The Obama Administration and the Press," warning that in Washington "government officials are increasingly afraid to talk to the press." Written by a former executive editor of The Washington Post, Leonard Downie Jr., the report is a damning indictment of the U.S. government's clampdown.

But the maneuvers against the press are just a small part of the U.S. snooping program at home and abroad. The NSA -- the world's most powerful and farthest-reaching surveillance agency -- spies on public and private realms with tremendous capabilities that encourage other countries to follow suit.

"The U.S. government has gone further than any previous government ... in setting up machinery that satisfies certain tendencies that are in the genetic code of totalitarianism," Jonathan Schell wrote last fall in The Nation. "One is the ambition to invade personal privacy without check or possibility of individual protection."

That ambition, he noted, "was impossible in the era of mere phone wiretapping, before the recent explosion of electronic communications -- before the cellphones that disclose the whereabouts of their owners, the personal computers with their masses of personal data and easily penetrated defenses, the e-mails that flow through readily tapped cables and servers, the biometrics, the street-corner surveillance cameras. But now, to borrow the name of an intelligence program from the (George W.) Bush years, Total Information Awareness is technologically within reach."

Bush set those efforts in motion, and his successor has extended them. No wonder Obama received such a chilly reception when he visited Germany last summer, a few weeks after the first revelations about NSA spying.

In June, Wolfgang Schmidt, once a lieutenant colonel in the former East Germany's secret police, the Stasi, commented on the NSA's domestic surveillance program, making the disbanded Stasi's work during the 1980s seem tiny and crude in comparison. "For us, this would have been a dream come true," Schmidt told a reporter.

Whatever the reach of government surveillance might be, the standard claims of incorruptibility are nonsense. "It is the height of naivete to think that once collected, this information won't be used," said Schmidt. "The only way to protect the people's privacy is not to allow the government to collect their information in the first place."

Today a popular myth is that rapid digital advances make more surveillance inevitable. Technology is a convenient scapegoat for escalating invasions of privacy. But there is nothing inherent in technological progress that requires such violations of human rights and civil liberties.

The overarching problems are not technological; they are political -- and they have to do with who has power, how they got it and what they are doing with it. Democracy is at stake, and, as the Feb. 11 protests indicate, democracy is the potential solution.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Norman Solomon is the national director of RootsAction.org and executive director of the Institute for Public Accuracy. The paperback edition of his latest book, War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine, includes an afterword about the Gaza war.

The mind-boggling scope of the NSA's surveillance continues to make front-page news as a political story. But its most pernicious effects are social and psychological. We are getting accustomed to Big Brother. Our daily lives are now accessible to prying eyes and ears no farther away than the nearest computer or cellphone. Unless we directly challenge the system of mass surveillance now, the ruling elites may understand our complacency as consent, with results that extend the reach of surveillance and its damaging consequences. Even as it grows more familiar, this bulk collection of data is corroding civil society.

Mass surveillance amounts to a siege that subtly constrains our freedoms and injures social relations. Freewheeling civic engagement is in the line of fire. The surveillance state generates fearful conformity.

To resist the growing possibility of this mind-set, Feb. 11 was designated The Day We Fight Back, with more than 5,300 nonprofit groups and private companies joining forces to demand an end to the numbing tyranny of mass surveillance.

Where does this resolute anger come from? The widespread public discontent seeks to reject the myriad ways the NSA's spying has undermined and continues to undermine our common humanity.

The NSA's partnership with the cutting-edge tech sector has given immense power to the government and gigantic profits to private firms. It is an ongoing collaboration that makes a digital mockery of the Fourth Amendment commitment to "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects."

By closely monitoring those it claims to respect and protect, the U.S. government is doing enormous and cumulative damage. In realms that stretch from public to intimate, people are growing acutely aware that much of what they say and do is becoming officially retrievable -- and might be used against them, someday, somehow.

Whether engaged in a phone discussion, email correspondence, online searches, banter at a party or even a quiet conversation at home, people are losing a sense of activity that is truly private. The omniscience wielded by authorities is crowding into the most human of spaces, casting an ominous shadow over free communication and boosting inclinations to self-censor.

The mistrust and cynicism due to regular surveillance only gets worse as top officials resort to mendacity to defend it. "We don't have a domestic spying program," President Barack Obama declared on "The Tonight Show" in early August, two months after the NSA scandal broke. He insisted, "There is no spying on Americans."

This lying became part of a whole dissembling repertoire. Five months later, in his much ballyhooed Jan. 17 speech about the NSA, Obama was still in deception mode, proclaiming, "The bottom line is that people around the world, regardless of their nationality, should know that the United States is not spying on ordinary people who don't threaten our national security."

But NSA documents provided by Snowden make clear that the U.S. government is spying on ordinary people every day -- on a humongous scale.

Along the way, surveillance has played a key role in the government's moves against whistle-blowers and journalists. In September the Obama administration proudly announced a long prison sentence for a former FBI agent who was tripped up by the Department of Justice's secret seizure of call records for 20 phone lines used by Associated Press reporters and editors. To all but the most pliant journalists, this trend is ominous and already destructive.

Even the media establishment is sounding the alarm. The Committee to Protect Journalists, a blue-ribbon press-freedom watchdog, issued an extraordinary report on Oct. 10, "The Obama Administration and the Press," warning that in Washington "government officials are increasingly afraid to talk to the press." Written by a former executive editor of The Washington Post, Leonard Downie Jr., the report is a damning indictment of the U.S. government's clampdown.

But the maneuvers against the press are just a small part of the U.S. snooping program at home and abroad. The NSA -- the world's most powerful and farthest-reaching surveillance agency -- spies on public and private realms with tremendous capabilities that encourage other countries to follow suit.

"The U.S. government has gone further than any previous government ... in setting up machinery that satisfies certain tendencies that are in the genetic code of totalitarianism," Jonathan Schell wrote last fall in The Nation. "One is the ambition to invade personal privacy without check or possibility of individual protection."

That ambition, he noted, "was impossible in the era of mere phone wiretapping, before the recent explosion of electronic communications -- before the cellphones that disclose the whereabouts of their owners, the personal computers with their masses of personal data and easily penetrated defenses, the e-mails that flow through readily tapped cables and servers, the biometrics, the street-corner surveillance cameras. But now, to borrow the name of an intelligence program from the (George W.) Bush years, Total Information Awareness is technologically within reach."

Bush set those efforts in motion, and his successor has extended them. No wonder Obama received such a chilly reception when he visited Germany last summer, a few weeks after the first revelations about NSA spying.

In June, Wolfgang Schmidt, once a lieutenant colonel in the former East Germany's secret police, the Stasi, commented on the NSA's domestic surveillance program, making the disbanded Stasi's work during the 1980s seem tiny and crude in comparison. "For us, this would have been a dream come true," Schmidt told a reporter.

Whatever the reach of government surveillance might be, the standard claims of incorruptibility are nonsense. "It is the height of naivete to think that once collected, this information won't be used," said Schmidt. "The only way to protect the people's privacy is not to allow the government to collect their information in the first place."

Today a popular myth is that rapid digital advances make more surveillance inevitable. Technology is a convenient scapegoat for escalating invasions of privacy. But there is nothing inherent in technological progress that requires such violations of human rights and civil liberties.

The overarching problems are not technological; they are political -- and they have to do with who has power, how they got it and what they are doing with it. Democracy is at stake, and, as the Feb. 11 protests indicate, democracy is the potential solution.

Norman Solomon is the national director of RootsAction.org and executive director of the Institute for Public Accuracy. The paperback edition of his latest book, War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine, includes an afterword about the Gaza war.

The mind-boggling scope of the NSA's surveillance continues to make front-page news as a political story. But its most pernicious effects are social and psychological. We are getting accustomed to Big Brother. Our daily lives are now accessible to prying eyes and ears no farther away than the nearest computer or cellphone. Unless we directly challenge the system of mass surveillance now, the ruling elites may understand our complacency as consent, with results that extend the reach of surveillance and its damaging consequences. Even as it grows more familiar, this bulk collection of data is corroding civil society.

Mass surveillance amounts to a siege that subtly constrains our freedoms and injures social relations. Freewheeling civic engagement is in the line of fire. The surveillance state generates fearful conformity.

To resist the growing possibility of this mind-set, Feb. 11 was designated The Day We Fight Back, with more than 5,300 nonprofit groups and private companies joining forces to demand an end to the numbing tyranny of mass surveillance.

Where does this resolute anger come from? The widespread public discontent seeks to reject the myriad ways the NSA's spying has undermined and continues to undermine our common humanity.

The NSA's partnership with the cutting-edge tech sector has given immense power to the government and gigantic profits to private firms. It is an ongoing collaboration that makes a digital mockery of the Fourth Amendment commitment to "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects."

By closely monitoring those it claims to respect and protect, the U.S. government is doing enormous and cumulative damage. In realms that stretch from public to intimate, people are growing acutely aware that much of what they say and do is becoming officially retrievable -- and might be used against them, someday, somehow.

Whether engaged in a phone discussion, email correspondence, online searches, banter at a party or even a quiet conversation at home, people are losing a sense of activity that is truly private. The omniscience wielded by authorities is crowding into the most human of spaces, casting an ominous shadow over free communication and boosting inclinations to self-censor.

The mistrust and cynicism due to regular surveillance only gets worse as top officials resort to mendacity to defend it. "We don't have a domestic spying program," President Barack Obama declared on "The Tonight Show" in early August, two months after the NSA scandal broke. He insisted, "There is no spying on Americans."

This lying became part of a whole dissembling repertoire. Five months later, in his much ballyhooed Jan. 17 speech about the NSA, Obama was still in deception mode, proclaiming, "The bottom line is that people around the world, regardless of their nationality, should know that the United States is not spying on ordinary people who don't threaten our national security."

But NSA documents provided by Snowden make clear that the U.S. government is spying on ordinary people every day -- on a humongous scale.

Along the way, surveillance has played a key role in the government's moves against whistle-blowers and journalists. In September the Obama administration proudly announced a long prison sentence for a former FBI agent who was tripped up by the Department of Justice's secret seizure of call records for 20 phone lines used by Associated Press reporters and editors. To all but the most pliant journalists, this trend is ominous and already destructive.

Even the media establishment is sounding the alarm. The Committee to Protect Journalists, a blue-ribbon press-freedom watchdog, issued an extraordinary report on Oct. 10, "The Obama Administration and the Press," warning that in Washington "government officials are increasingly afraid to talk to the press." Written by a former executive editor of The Washington Post, Leonard Downie Jr., the report is a damning indictment of the U.S. government's clampdown.

But the maneuvers against the press are just a small part of the U.S. snooping program at home and abroad. The NSA -- the world's most powerful and farthest-reaching surveillance agency -- spies on public and private realms with tremendous capabilities that encourage other countries to follow suit.

"The U.S. government has gone further than any previous government ... in setting up machinery that satisfies certain tendencies that are in the genetic code of totalitarianism," Jonathan Schell wrote last fall in The Nation. "One is the ambition to invade personal privacy without check or possibility of individual protection."

That ambition, he noted, "was impossible in the era of mere phone wiretapping, before the recent explosion of electronic communications -- before the cellphones that disclose the whereabouts of their owners, the personal computers with their masses of personal data and easily penetrated defenses, the e-mails that flow through readily tapped cables and servers, the biometrics, the street-corner surveillance cameras. But now, to borrow the name of an intelligence program from the (George W.) Bush years, Total Information Awareness is technologically within reach."

Bush set those efforts in motion, and his successor has extended them. No wonder Obama received such a chilly reception when he visited Germany last summer, a few weeks after the first revelations about NSA spying.

In June, Wolfgang Schmidt, once a lieutenant colonel in the former East Germany's secret police, the Stasi, commented on the NSA's domestic surveillance program, making the disbanded Stasi's work during the 1980s seem tiny and crude in comparison. "For us, this would have been a dream come true," Schmidt told a reporter.

Whatever the reach of government surveillance might be, the standard claims of incorruptibility are nonsense. "It is the height of naivete to think that once collected, this information won't be used," said Schmidt. "The only way to protect the people's privacy is not to allow the government to collect their information in the first place."

Today a popular myth is that rapid digital advances make more surveillance inevitable. Technology is a convenient scapegoat for escalating invasions of privacy. But there is nothing inherent in technological progress that requires such violations of human rights and civil liberties.

The overarching problems are not technological; they are political -- and they have to do with who has power, how they got it and what they are doing with it. Democracy is at stake, and, as the Feb. 11 protests indicate, democracy is the potential solution.