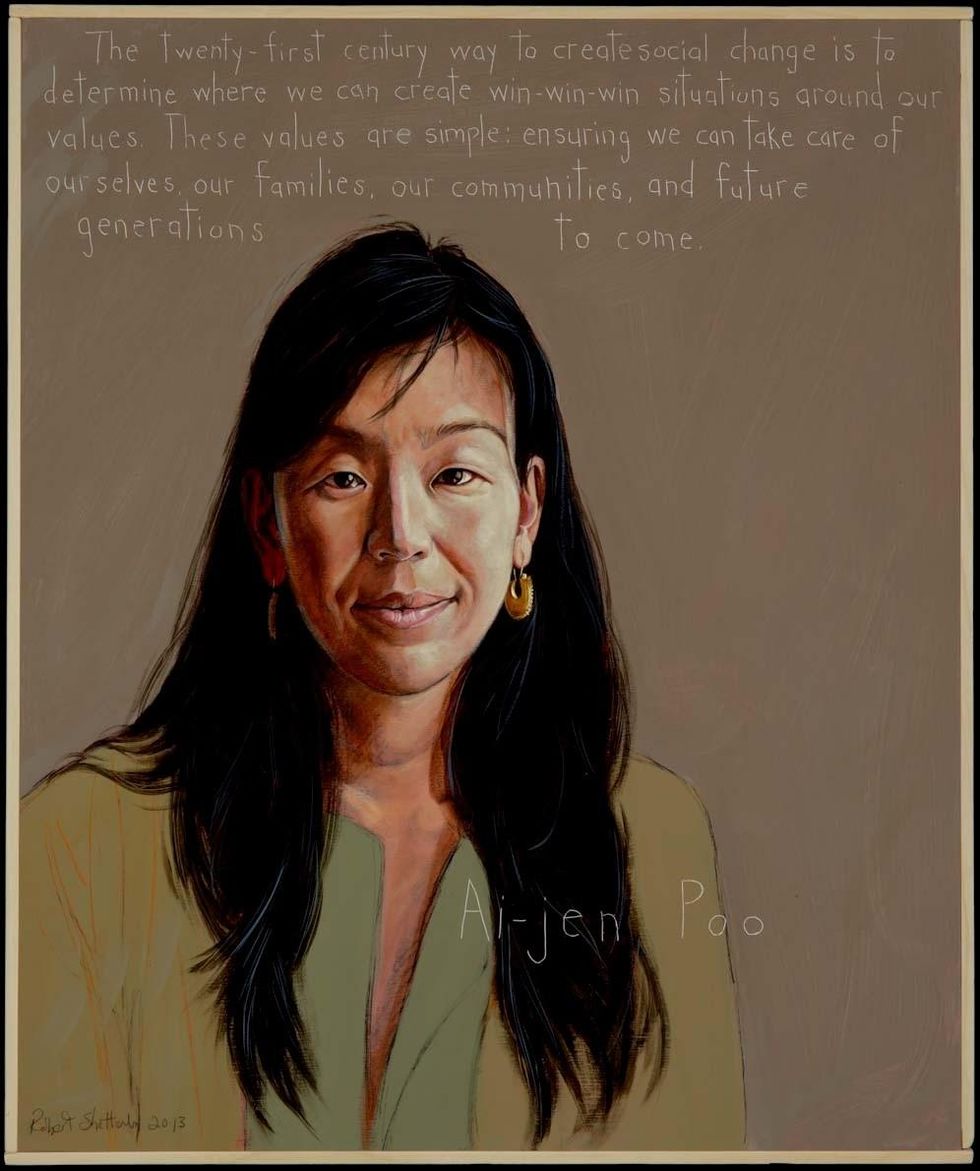

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time.This painting of labor rights leader Ai-Jen Poo is his latest portrait of those who have dedicated their life to to improving worker protections in the name of the common good. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

"Socrates had it wrong; it is not the unexamined but finally the uncommitted life that is not worth living. Descartes too was mistaken; "Cogito ergo sum--I think therefore I am"? Nonsense. "Amo ergo sum--I love therefore I am." -William Sloane Coffin

When, during the Great depression, the US Congress passed some of the first protections for workers in this country -- largely in response to enormous worker demand, strikes and protests, and the urging of Secretary of Labor France Perkins -- there were many who were still left out. The excluded were included many women and African Americans -- domestic, agricultural, and retail and service workers, who didn't get the benefit of the minimum wage and maximum hours, the right to organize, workers compensation, the end of child labor, and social security. This was no accident. Prejudice against women and blacks was still politically acceptable, and the lobby to exclude these workers from protection was strong.

In fact, it's taken over 70 years for domestic and in-home care workers to win some protections. These workers are still primarily women. They are white, black and immigrants. They are hard to organize because each has a different employer, they are dispersed widely, have little communication with each other, often speak little English, may be undocumented, and are afraid to complain (even if they knew to whom they could complain) for fear of losing their jobs. Many are abused physically, financially and emotionally. Over the past few decades, organizing inside a business where the workers are congregated has become much harder, so it would seem that organizing domestic workers would be damn near impossible.

"Narrative power is the real key to significant change--whose story gets told and how? And, she says, the most powerful way to change a narrative is with love."

Enter Ai-jen Poo. Ai-jen is a Taiwanese-American from scientist parents who instilled in their daughter an ethic made up of equal parts activism and compassion. She learned the power of direct action protest as a student at Columbia University in New York and after college while working for Asian rights. During that time she began to hear the stories of domestic workers, how they were taken advantage of, how they had no recourse. In New York in 2002, she founded Domestic Workers United. She and her fellow organizers went to the places where domestic workers congregate when they are caring for children--parks, playgrounds, churches--and on their way to work--bus and subway stops--and started up conversations. Those conversations led to actions and suits against abusive employers and then to campaigns to change the laws.

Early on Ai-jen realized that not only was she trying to organize workers in an unconventional situation, but that she had to do it in an unconventional way. Typically, worker solidarity has been enhanced by pitting us against them, workers against bosses, the many wage earners against the few salaried folks. But Ai-jen knew that her goal would not be won by opposition. Don't people who employ nannies and care workers want the best, most loving care for their children and parents? Are they going to get that kind of care from people they short change and abuse? Ai-jen's model, she realized, should not be us against them but us with them. Organizing with love, she calls it. She organizes employers to understand how much they gain by treating their employees well. Ai-jen Poo is anything but naive. She knows that in the name of love one often has to provoke conflict, be tough about what you want. When I went to meet her in the offices of the National Domestic Workers Alliance on 7th Avenue in Manhattan, she talked about three kinds of power available to people who don't have the power of ownership and wealth: Political, disruptive, and narrative. Workers, minorities, women and others fighting for social and economic justice have always used all three, but, Ai-jen says, the advances won through politics and protest only hold if the narrative changes, if the larger society embraces the justice of the cause. Narrative power is the real key to significant change--whose story gets told and how? And, she says, the most powerful way to change a narrative is with love.

I have painted a number of labor organizers--Mother Jones, Cesar Chavez, Eugene Debs, Emma Tenayuca--but none quite like Ai-jen Poo. Those others were in great oppositional struggles where powerful interests would routinely resort to violent tactics, usually with impunity, to maintain their power and profit. But those powers aren't calling out the Goon Squad to rough up the beloved nannie of their three year old daughter or the caregiver loved by their infirm mother. Well organized workers can shut down a factory and cut off the flow of profit to the boss. A poorly treated nannie may not read a bed time story to a toddler or keep her patience with a senile parent. It takes a different kind of organizing.

Ai-jen Poo had great success in New York with Domestic Workers United. The New York legislature passed domestic worker standards for overtime pay, paid days off, and protection against discrimination and harassment. In 2007, she went on to help found and direct the National Domestic Workers Alliance, a consortium of 39 national organizations supporting domestic worker rights. And this year the NDWA achieved major successes: California passed a domestic worker protection act guaranteeing overtime pay; and on September 17, the Obama administration announced new rules extending the Fair Labor Standards Act to include the 800,000 to 2 million home healthcare workers.

Ai-jen Poo has also brought together 200 organizations to launch a new initiative--Caring Across Generations. This year is the first year of the "age wave." Every eight seconds, an American will turn 65. In the coming years, more and more members of our communities will need care, just as more workers need dignified jobs. At a time when we desperately need new jobs, new paths to citizenship, and new solutions to persistent crises in care, this broad coalition of people from all walks of life is coming together to push for change that embraces both the elderly and immigrants. Ai-jen has said, "We want to build a movement that brings together people who need care and support with workers who can provide it, and to do it in a way that preserves everybody's choices, independence, and dignity. We want to create quality jobs so that caregivers can support their own families and the elderly won't bankrupt their children."

Most social movements for rights and protections are based on the simple and militant dictum of Frederick Douglass: "Power concedes nothing without a demand; it never did and it never will." But how shall we use that demand? As a part of an ongoing struggle of irreparable antagonisms, or as a negotiation between members of a community who know that they must work together for the common good?

The power of Ai-jen Poo's narrative is that it is the one that heals, the one that finds common ground, the one that builds community, the one that deepens our humanity, the one that gives us permission to not be our brother's keeper, but, as William Sloane Coffin says, our brother's brother, and our sister's sister.