The film takes all the caricatures of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and admitted source Pfc Bradley Manning, exaggerates them, and adds some new ones. The attacks range from the petty (Manning is effeminate and Assange is a hacker-hero enamored with his newfound rock star status), to the simply bizarre (Assange is out to impregnate unwitting women and spread his seed all over the planet) and impossible (during the era of "Don't ask, don't tell," while serving in the military, Manning was taking hormone therapy.)

Gibney spins a narrative about the "transformations" of both Manning and Assange: "[i]n online chats with WikiLeaks, Manning's thoughts changed," and this is inextricably intertwined with his gender-identity crisis. Meanwhile, Assange has an almost-religious devotion to transparency, but turns into a law-dodging criminal who wants to keep secret his many salacious deeds.

Ironically, it is Gibney's transformation in how he views his subjects - a transformation that occurs over the course of making this film - that follows the quintessential whistleblower nightmare, with Gibney playing the role of retaliator. In the typical whistleblower ordeal, a person trying to expose disturbing and often illegal acts by the government runs afoul of the power structure, which then reprises with fantastical smears and attempts to ruin that individual personally and professionally by focusing on character assassination rather than conscience.

In Manning's own words, he "saw incredible things, awful things . . . things that belonged in the public domain". He then made the most massive whistleblower disclosures in the history of the world, exposing war crimes and the dark underbelly of our misadventures in Iraq and Afghanistan. He hoped his disclosures would spur "discussion, debates, and reforms" and "want[ed] people to know the truth, no matter who they are, because without information you cannot make informed decisions as a public".

The government swiftly retaliated, arresting Manning, whom President Obama said "broke the law", and launching a worldwide manhunt for Julian Assange, whom vice president Joe Biden labeled a "hi-tech terrorist".

By spending an inordinate amount of the film on Assange's alleged personal misdeeds and Manning's gender dysmorphia, Gibney, who should know better, given that his other stellar socio-political documentaries (Taxi to the Dark Side and Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room) have relied on and benefitted from whistleblowers, perpetuates the usual smears that the government levels against whistleblowers and their allies: that they are vengeful, unstable, or out for fame and profit.

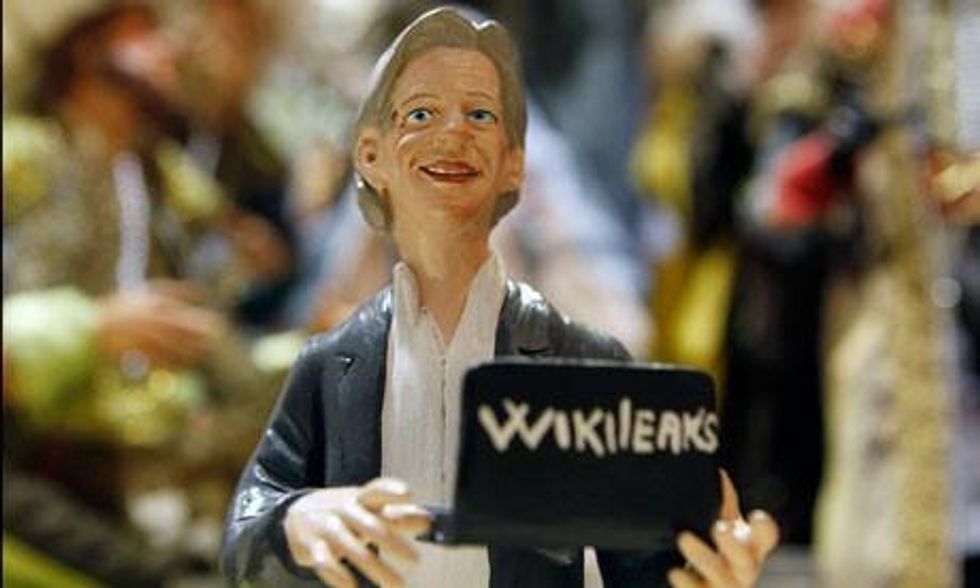

Taking a page out of the government playbook, the film focuses on the person rather than the substance of his complaints. It attacks their credibility rather than answering their criticism. The film expends tremendous resources tarnishing those who broke the code of silence, which both Manning and Assange did in their own ways, on a massive and unprecedented scale with a massive megaphone called WikiLeaks.

In publicity for the film, Gibney minces no words in describing his true feelings about whistleblowers:

"I think [Bradley Manning] raises big issues about who whistleblowers are, because they are alienated people who don't get along with people around them, which motivates them to do what they do."

Legally speaking, a whistleblower's motive is irrelevant. As long as a government employee discloses what he or she reasonably believes evidences fraud, waste, abuse, illegality, or a danger to public health or safety, it matters not a whit if the revelation is beneficent, self-aggrandizing, naive, or for financial gain (there are actually a number of whistleblower reward laws that pay out money as an incentive for coming forward.)

In the legal calculus, motive is irrelevant because whistleblowers are human beings who often have flawed and complicated motives, especially when most all of them have been suffering the death-by-a-thousand-paper-cuts treatment (ostracization, demotion, etc) that almost universally precedes their disclosures. This could also explain why people like National Security Agency whistleblower Thomas Drake, who was filmed for the movie, ended up on the cutting-room floor. He is far too vanilla, upright, well-regarded - and perhaps the biggest strike of all, told producer Alexis Bloom that he considered Manning a whistleblower - to fit Gibney's "troubled whistleblower" mold.

While Gibney presents the documentary as a search for the truth about Manning's motivations and Assange's duplicity, the truth it actually reveals is that even an enlightened Academy award-winning documentarian of Gibney's caliber can be tarnished by the power of the government's self-serving stereotype of whistleblowers and the people who support them.