The US Food Aid Industry: Food for Peace or Food for Profit?

On February 21st, 69 organizations submitted a letter to President Barack Obama in support of continued funding for Public Law 480 (also known as Food for Peace) and Food for Progress international food aid programs in the FY 2014 budget, and opposing rumored proposals to shift resources to local and regional commodity

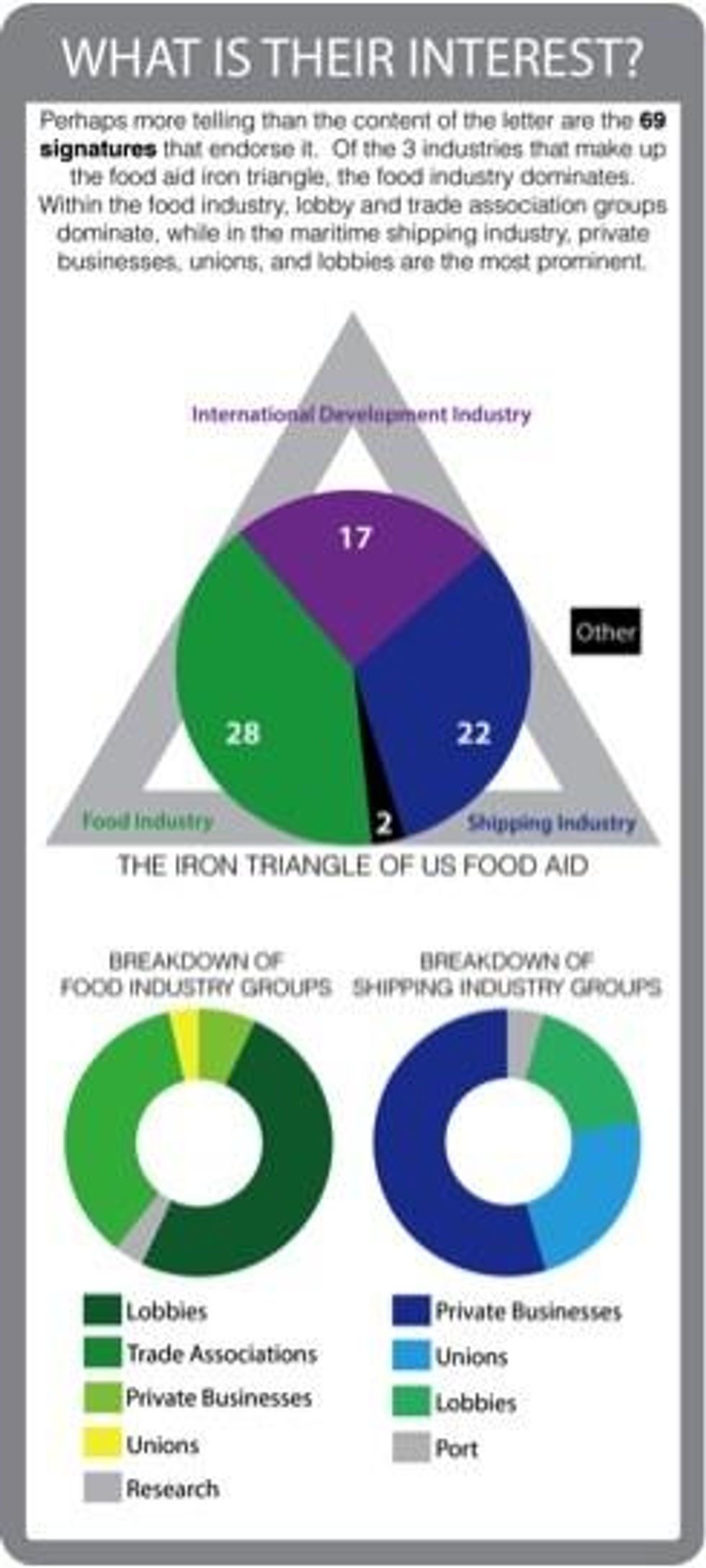

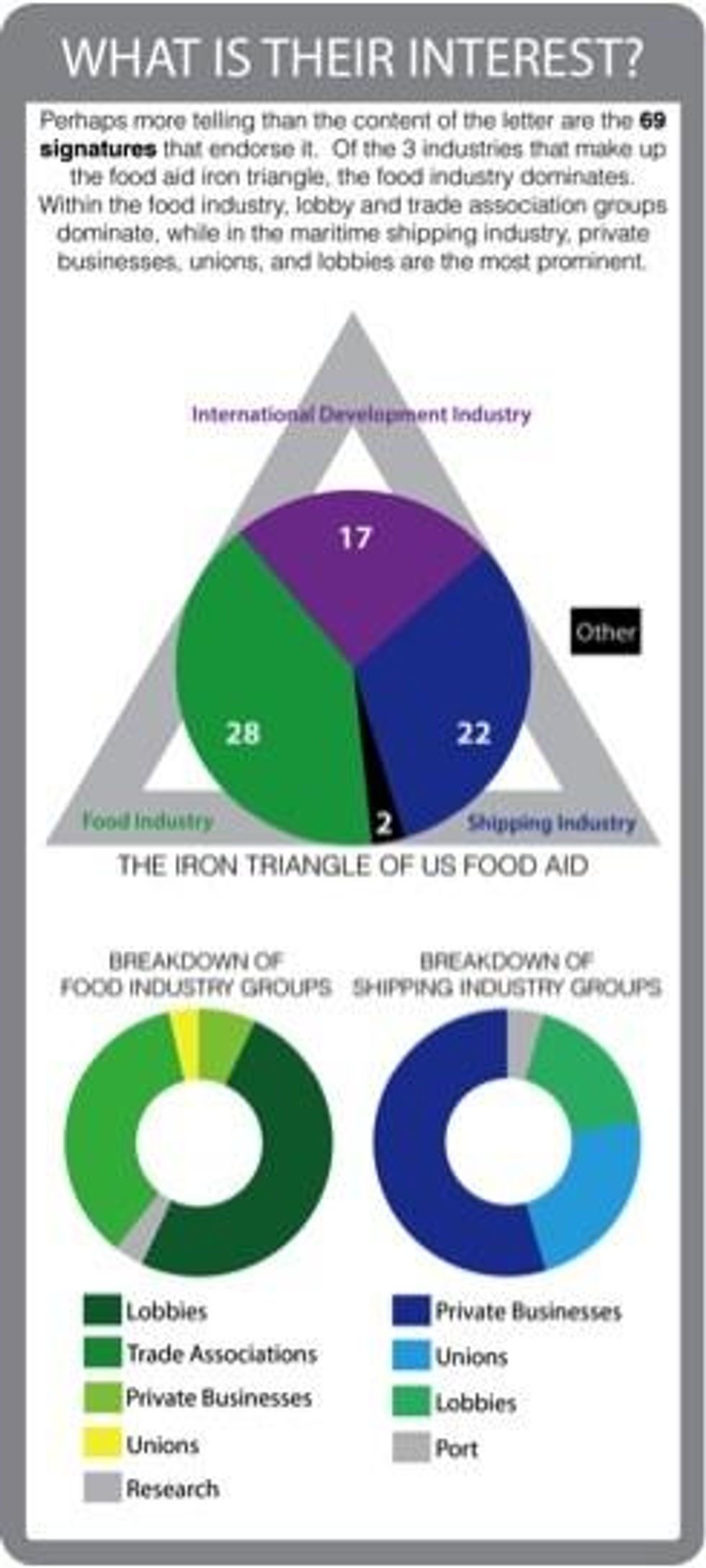

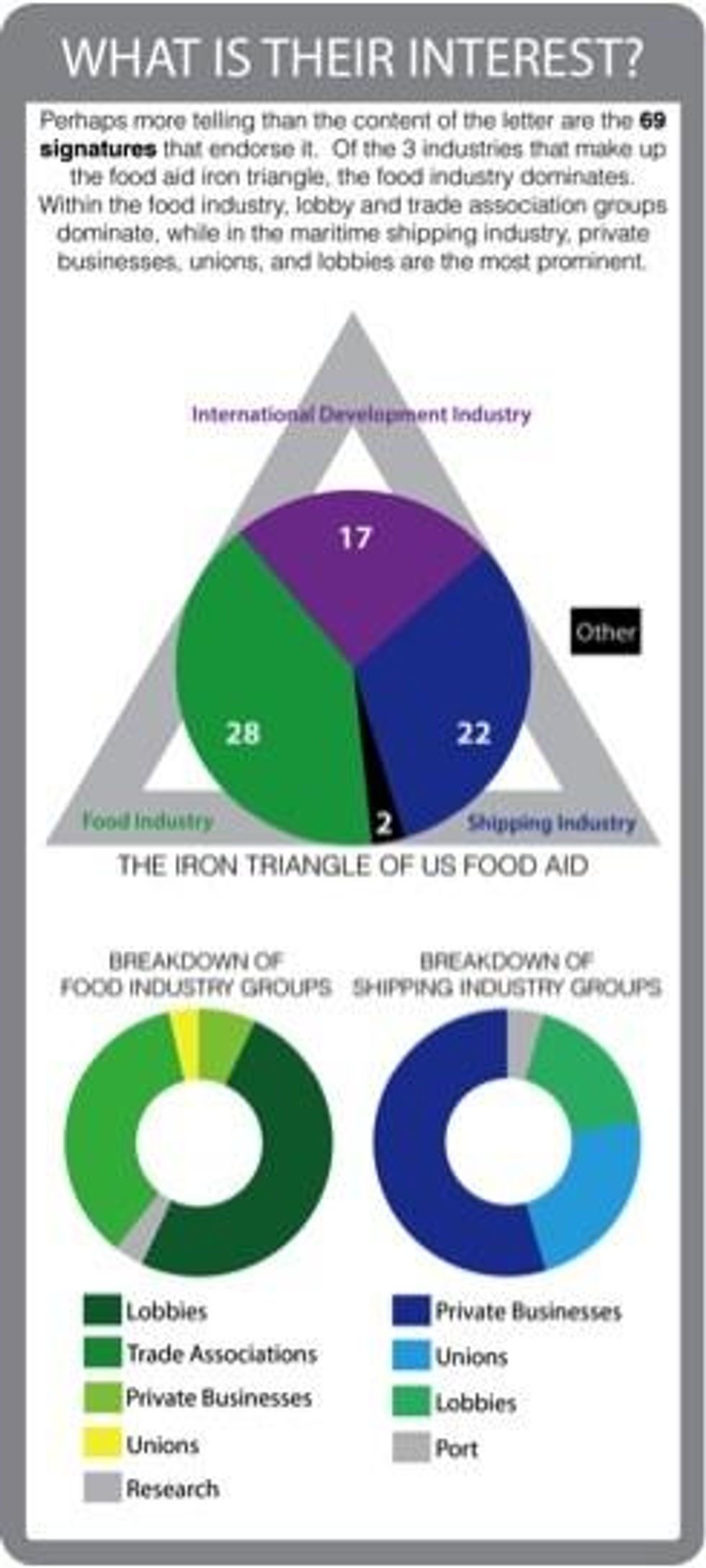

On February 21st, 69 organizations submitted a letter to President Barack Obama in support of continued funding for Public Law 480 (also known as Food for Peace) and Food for Progress international food aid programs in the FY 2014 budget, and opposing rumored proposals to shift resources to local and regional commodity procurement. The signatory organizations were comprised almost exclusively by the iron triangle of US food aid spending recipients (the US agribusiness, shipping, and international development industries). Funding, which is attached to the Farm Bill, has been reauthorized by President Obama under Title VII of the fiscal cliff legislation through this September. However, these food aid programs depend on congressional appropriations, which have only been approved through March 27th. Big changes, or more of the same, could be in store for food aid legislation in the near future.

Currently, US food aid is dominated by in-kind donations (direct gifts of food)--an infamously inefficient system--and monetization, a system in which US agricultural commodities are donated to development organizations so that they can sell them to fund projects. This approach to food aid has been widely criticized for decades, including by the Congress' Government Accountability Office. The NGO Oxfam, once a beneficiary of PL 480, has been calling for food aid reform for years, putting an emphasis on the need for local commodity procurement. CARE, one of the three major NGO distributors of US food aid across the world, recently followed suit. Canada and Europe have shifted nearly all food aid resources away from in-kind distribution in favor of local procurement. The US, sticking to its M.O., is the loner; in 2007, 99.3% of US food aid was in-kind.

The letter to President Obama notes that "food aid programs have enjoyed strong bipartisan support for nearly 60 years because they work." The question is, for whom? By law, 75% of food aid from the US must be purchased, processed, transported, and distributed by US companies. In 2002, just two US companies--ADM and Cargill--controlled 75% of the global grain trade, with US government contracts to manage and distribute 30% of food aid grains. Only four companies control 84% of the transport and delivery of food aid worldwide.

The letter continues by stating: "Food for Progress expands business and income opportunities along the agricultural value chain." This has certainly been the case for the US food, maritime shipping, and international development industries. For recipient countries, however, food aid has a long history of displacing local production. According to a 2005 Oxfam report, "There is strong historical evidence that the use of food aid tends to correlate with long-term dependence on food imports." Due to foreign exchange difficulties during the 1990s, the Philippines was unable to sustain imports of soybean meal. PL 480 food aid was used to finance the purchase of US exports. By the early 2000s, the Philippines was the largest market for US soybean meal worldwide and 90% of total imports came from the US. This points to another use of food aid: the explicit expansion of markets abroad for US products. USAID states, "Of the 50 largest customers for US agricultural goods, 43 -- including Egypt, Indonesia, Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand -- formerly received food assistance. In short, aid leads to trade, from which Americans stand to benefit directly."

The effects of food aid are not limited only to local food production, processing, and distribution. It has also outcompeted national exporters, as in the case of Guyana and Jamaica. When US food aid rice poured in to Jamaica, Guyanese producers were unable to maintain a hold in the Jamaican rice market. This process shifts poverty from one country to another, effectively defeating the public premise of food aid.

Food aid is perhaps most infamous for the practice of dumping, or disposing of surplus food commodities in vulnerable national markets. In this case, food aid functions as just another US agricultural subsidy. In 2007, despite growing hunger, food aid fell globally by 15%, the lowest level since 1961. This reflects the tendency of food aid to respond to international grain prices--and not to the food needs of the poor. When the price of cereals is low, Northern countries and transnational grain companies sell their commodities through food aid programs. When prices are high, they sell their grains on the global market. So, when people are less able to buy food, less food aid arrives.

In contrast, local and regional procurement of food aid, along with cash vouchers, could decrease US food aid costs by 50%, bolster the development of local food markets and long-term economies, and allow US food aid recipient countries to build their own assistance programs. Timi Gerson of the American Jewish World Service (AJWS) told IPS that a switch to local procurement "would be able to reach 17 million more people - so we're only getting to about two-thirds of the people we could be." An anti-hunger coalition led by AJWS, Oxfam America, and Bread for the World Institute issued a joint statement saying: "Current regulations on the food aid program in the Farm Bill protect special interests," aka the iron triangle of food aid, "at the expense of the hungry, and [that means] that more than a quarter of every dollar the U.S. spends on food aid goes to waste."

The 2008 Farm Bill authorized a Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement pilot program, which funds cash food aid projects through grants and uses cooperative agreements for local procurement during food crises. Detailed results of the 2009 to 2011 pilot projects were reported to the USDA by grantees. A Cornell study of the results indicated that the pilot projects achieved greater efficiency and effectiveness of food aid delivery, while avoiding the negative impacts, such as displacement of local production and import dependencies that in-kind food aid has caused historically. When sourced locally versus when sourced in the US and shipped across oceans, cereals cost on average 54% less and pulses 24% less. Average delivery time was also reduced by 62% or about 14 weeks. For victims of natural disasters, this time window could be the difference between life and death.

The letter in question makes several accurate statements yet omits the true impacts of food aid on recipient countries. It does, however, contain one lie, stating that PL 480 facilitates "developmental programs to end the cycle of hunger," when in fact it propagates it. Hunger is big business. Food for Peace ends up looking a lot more like Food for Profit. The letter ends with one final truth, declaring that food aid programs are "some of our most effective, lowest-cost national security tools." By handicapping local food markets across the world, food aid keeps poor countries poor and compliant, and provides US-based companies with dependable markets for the dumping of surplus food commodities when global grain prices are low. Rice and wheat cost a lot less than bombs.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

On February 21st, 69 organizations submitted a letter to President Barack Obama in support of continued funding for Public Law 480 (also known as Food for Peace) and Food for Progress international food aid programs in the FY 2014 budget, and opposing rumored proposals to shift resources to local and regional commodity procurement. The signatory organizations were comprised almost exclusively by the iron triangle of US food aid spending recipients (the US agribusiness, shipping, and international development industries). Funding, which is attached to the Farm Bill, has been reauthorized by President Obama under Title VII of the fiscal cliff legislation through this September. However, these food aid programs depend on congressional appropriations, which have only been approved through March 27th. Big changes, or more of the same, could be in store for food aid legislation in the near future.

Currently, US food aid is dominated by in-kind donations (direct gifts of food)--an infamously inefficient system--and monetization, a system in which US agricultural commodities are donated to development organizations so that they can sell them to fund projects. This approach to food aid has been widely criticized for decades, including by the Congress' Government Accountability Office. The NGO Oxfam, once a beneficiary of PL 480, has been calling for food aid reform for years, putting an emphasis on the need for local commodity procurement. CARE, one of the three major NGO distributors of US food aid across the world, recently followed suit. Canada and Europe have shifted nearly all food aid resources away from in-kind distribution in favor of local procurement. The US, sticking to its M.O., is the loner; in 2007, 99.3% of US food aid was in-kind.

The letter to President Obama notes that "food aid programs have enjoyed strong bipartisan support for nearly 60 years because they work." The question is, for whom? By law, 75% of food aid from the US must be purchased, processed, transported, and distributed by US companies. In 2002, just two US companies--ADM and Cargill--controlled 75% of the global grain trade, with US government contracts to manage and distribute 30% of food aid grains. Only four companies control 84% of the transport and delivery of food aid worldwide.

The letter continues by stating: "Food for Progress expands business and income opportunities along the agricultural value chain." This has certainly been the case for the US food, maritime shipping, and international development industries. For recipient countries, however, food aid has a long history of displacing local production. According to a 2005 Oxfam report, "There is strong historical evidence that the use of food aid tends to correlate with long-term dependence on food imports." Due to foreign exchange difficulties during the 1990s, the Philippines was unable to sustain imports of soybean meal. PL 480 food aid was used to finance the purchase of US exports. By the early 2000s, the Philippines was the largest market for US soybean meal worldwide and 90% of total imports came from the US. This points to another use of food aid: the explicit expansion of markets abroad for US products. USAID states, "Of the 50 largest customers for US agricultural goods, 43 -- including Egypt, Indonesia, Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand -- formerly received food assistance. In short, aid leads to trade, from which Americans stand to benefit directly."

The effects of food aid are not limited only to local food production, processing, and distribution. It has also outcompeted national exporters, as in the case of Guyana and Jamaica. When US food aid rice poured in to Jamaica, Guyanese producers were unable to maintain a hold in the Jamaican rice market. This process shifts poverty from one country to another, effectively defeating the public premise of food aid.

Food aid is perhaps most infamous for the practice of dumping, or disposing of surplus food commodities in vulnerable national markets. In this case, food aid functions as just another US agricultural subsidy. In 2007, despite growing hunger, food aid fell globally by 15%, the lowest level since 1961. This reflects the tendency of food aid to respond to international grain prices--and not to the food needs of the poor. When the price of cereals is low, Northern countries and transnational grain companies sell their commodities through food aid programs. When prices are high, they sell their grains on the global market. So, when people are less able to buy food, less food aid arrives.

In contrast, local and regional procurement of food aid, along with cash vouchers, could decrease US food aid costs by 50%, bolster the development of local food markets and long-term economies, and allow US food aid recipient countries to build their own assistance programs. Timi Gerson of the American Jewish World Service (AJWS) told IPS that a switch to local procurement "would be able to reach 17 million more people - so we're only getting to about two-thirds of the people we could be." An anti-hunger coalition led by AJWS, Oxfam America, and Bread for the World Institute issued a joint statement saying: "Current regulations on the food aid program in the Farm Bill protect special interests," aka the iron triangle of food aid, "at the expense of the hungry, and [that means] that more than a quarter of every dollar the U.S. spends on food aid goes to waste."

The 2008 Farm Bill authorized a Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement pilot program, which funds cash food aid projects through grants and uses cooperative agreements for local procurement during food crises. Detailed results of the 2009 to 2011 pilot projects were reported to the USDA by grantees. A Cornell study of the results indicated that the pilot projects achieved greater efficiency and effectiveness of food aid delivery, while avoiding the negative impacts, such as displacement of local production and import dependencies that in-kind food aid has caused historically. When sourced locally versus when sourced in the US and shipped across oceans, cereals cost on average 54% less and pulses 24% less. Average delivery time was also reduced by 62% or about 14 weeks. For victims of natural disasters, this time window could be the difference between life and death.

The letter in question makes several accurate statements yet omits the true impacts of food aid on recipient countries. It does, however, contain one lie, stating that PL 480 facilitates "developmental programs to end the cycle of hunger," when in fact it propagates it. Hunger is big business. Food for Peace ends up looking a lot more like Food for Profit. The letter ends with one final truth, declaring that food aid programs are "some of our most effective, lowest-cost national security tools." By handicapping local food markets across the world, food aid keeps poor countries poor and compliant, and provides US-based companies with dependable markets for the dumping of surplus food commodities when global grain prices are low. Rice and wheat cost a lot less than bombs.

On February 21st, 69 organizations submitted a letter to President Barack Obama in support of continued funding for Public Law 480 (also known as Food for Peace) and Food for Progress international food aid programs in the FY 2014 budget, and opposing rumored proposals to shift resources to local and regional commodity procurement. The signatory organizations were comprised almost exclusively by the iron triangle of US food aid spending recipients (the US agribusiness, shipping, and international development industries). Funding, which is attached to the Farm Bill, has been reauthorized by President Obama under Title VII of the fiscal cliff legislation through this September. However, these food aid programs depend on congressional appropriations, which have only been approved through March 27th. Big changes, or more of the same, could be in store for food aid legislation in the near future.

Currently, US food aid is dominated by in-kind donations (direct gifts of food)--an infamously inefficient system--and monetization, a system in which US agricultural commodities are donated to development organizations so that they can sell them to fund projects. This approach to food aid has been widely criticized for decades, including by the Congress' Government Accountability Office. The NGO Oxfam, once a beneficiary of PL 480, has been calling for food aid reform for years, putting an emphasis on the need for local commodity procurement. CARE, one of the three major NGO distributors of US food aid across the world, recently followed suit. Canada and Europe have shifted nearly all food aid resources away from in-kind distribution in favor of local procurement. The US, sticking to its M.O., is the loner; in 2007, 99.3% of US food aid was in-kind.

The letter to President Obama notes that "food aid programs have enjoyed strong bipartisan support for nearly 60 years because they work." The question is, for whom? By law, 75% of food aid from the US must be purchased, processed, transported, and distributed by US companies. In 2002, just two US companies--ADM and Cargill--controlled 75% of the global grain trade, with US government contracts to manage and distribute 30% of food aid grains. Only four companies control 84% of the transport and delivery of food aid worldwide.

The letter continues by stating: "Food for Progress expands business and income opportunities along the agricultural value chain." This has certainly been the case for the US food, maritime shipping, and international development industries. For recipient countries, however, food aid has a long history of displacing local production. According to a 2005 Oxfam report, "There is strong historical evidence that the use of food aid tends to correlate with long-term dependence on food imports." Due to foreign exchange difficulties during the 1990s, the Philippines was unable to sustain imports of soybean meal. PL 480 food aid was used to finance the purchase of US exports. By the early 2000s, the Philippines was the largest market for US soybean meal worldwide and 90% of total imports came from the US. This points to another use of food aid: the explicit expansion of markets abroad for US products. USAID states, "Of the 50 largest customers for US agricultural goods, 43 -- including Egypt, Indonesia, Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand -- formerly received food assistance. In short, aid leads to trade, from which Americans stand to benefit directly."

The effects of food aid are not limited only to local food production, processing, and distribution. It has also outcompeted national exporters, as in the case of Guyana and Jamaica. When US food aid rice poured in to Jamaica, Guyanese producers were unable to maintain a hold in the Jamaican rice market. This process shifts poverty from one country to another, effectively defeating the public premise of food aid.

Food aid is perhaps most infamous for the practice of dumping, or disposing of surplus food commodities in vulnerable national markets. In this case, food aid functions as just another US agricultural subsidy. In 2007, despite growing hunger, food aid fell globally by 15%, the lowest level since 1961. This reflects the tendency of food aid to respond to international grain prices--and not to the food needs of the poor. When the price of cereals is low, Northern countries and transnational grain companies sell their commodities through food aid programs. When prices are high, they sell their grains on the global market. So, when people are less able to buy food, less food aid arrives.

In contrast, local and regional procurement of food aid, along with cash vouchers, could decrease US food aid costs by 50%, bolster the development of local food markets and long-term economies, and allow US food aid recipient countries to build their own assistance programs. Timi Gerson of the American Jewish World Service (AJWS) told IPS that a switch to local procurement "would be able to reach 17 million more people - so we're only getting to about two-thirds of the people we could be." An anti-hunger coalition led by AJWS, Oxfam America, and Bread for the World Institute issued a joint statement saying: "Current regulations on the food aid program in the Farm Bill protect special interests," aka the iron triangle of food aid, "at the expense of the hungry, and [that means] that more than a quarter of every dollar the U.S. spends on food aid goes to waste."

The 2008 Farm Bill authorized a Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement pilot program, which funds cash food aid projects through grants and uses cooperative agreements for local procurement during food crises. Detailed results of the 2009 to 2011 pilot projects were reported to the USDA by grantees. A Cornell study of the results indicated that the pilot projects achieved greater efficiency and effectiveness of food aid delivery, while avoiding the negative impacts, such as displacement of local production and import dependencies that in-kind food aid has caused historically. When sourced locally versus when sourced in the US and shipped across oceans, cereals cost on average 54% less and pulses 24% less. Average delivery time was also reduced by 62% or about 14 weeks. For victims of natural disasters, this time window could be the difference between life and death.

The letter in question makes several accurate statements yet omits the true impacts of food aid on recipient countries. It does, however, contain one lie, stating that PL 480 facilitates "developmental programs to end the cycle of hunger," when in fact it propagates it. Hunger is big business. Food for Peace ends up looking a lot more like Food for Profit. The letter ends with one final truth, declaring that food aid programs are "some of our most effective, lowest-cost national security tools." By handicapping local food markets across the world, food aid keeps poor countries poor and compliant, and provides US-based companies with dependable markets for the dumping of surplus food commodities when global grain prices are low. Rice and wheat cost a lot less than bombs.