Guns and Drugs: We Can Curb Gun Violence by Ending the War on Drugs

When a hail of bullets extinguished dozens of lives at an elementary school last month, the ugly consequences of the nation's gun culture shot into the media spotlight. The debate around gun control in the aftermath of Newtown has yielded confused policy proposals like further militarizing schools, or preemptively tracking mentally ill people.

When a hail of bullets extinguished dozens of lives at an elementary school last month, the ugly consequences of the nation's gun culture shot into the media spotlight. The debate around gun control in the aftermath of Newtown has yielded confused policy proposals like further militarizing schools, or preemptively tracking mentally ill people.

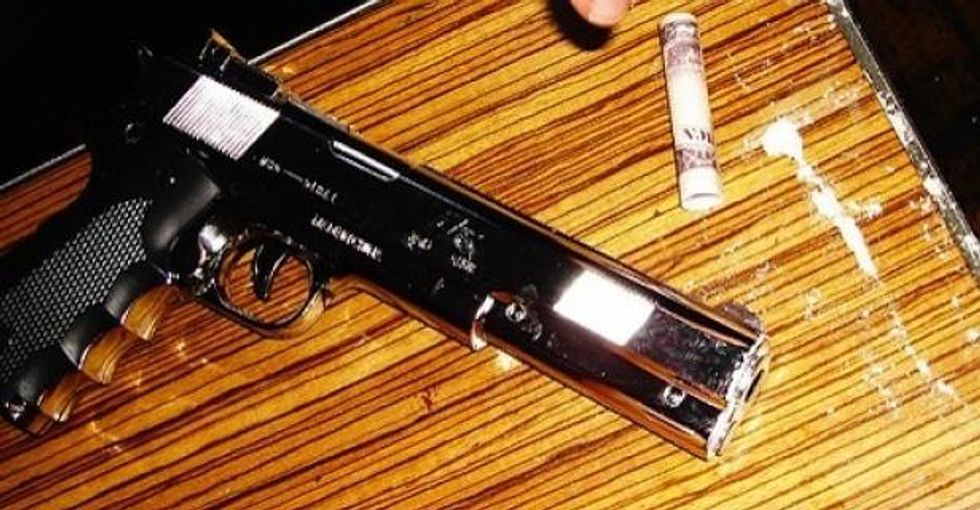

But a key aspect of the gun-control debate remains hiding in plain sight. There's a major driver of gun violence in the U.S. that is neither the bloodlust of the "criminally insane" nor the weakness of public security forces. Failed gun policy is a manifestation of another, arguably more expansive, irrational policy regime: the War on Drugs. While the most spectacular incidents of mass murder spark public panic, a more relevant, yet typically ignored, source of gun violence lies in the brutality born of the gun industry's marriage to drug prohibition policies.

For decades, the federal government has sought to eradicate drugs despite the utter futility of the effort and the devastating social, health and economic consequences of its tactics. While Sandy Hook triggered a national convulsion of disgust, the everyday casualties of the drug war have been met with relative silence. With annual gun homicides nationwide hovering around 10,000, a significant portion can be directly or indirectly linked to drug violence, though estimates for the death toll vary widely. (A recent CDC study of gang homicides, for example, notes that over 90 percent involve guns and the portion in different cities that were drug-related ranged from under five to about 25 percent.) Other analyses of national and international data likewise suggest a range of proportions depending on how drug-related killing is defined. Whatever the exact figure, the bottom line is that the drug war's institutionalized violence and oppression, fueled by "tough on crime" law enforcement, inflicts deep, needless social trauma on vulnerable communities. Underpinning that climate of violence are broader societal factors that also tend to be ignored in gun debates, including class and racial polarization.

Such tragedies seem worlds away from Newtown's massacre-perhaps because we've been sensitized over the years to accept the drug prohibition as a social imperative. In reality, the nation's enormously costly and destructive drug war greases the mechanics of our "culture" of gun violence, as much of the institutionalized violence is bound up with a policy regime that causes systematic harm in the name of public "safety."

Historical data [PDF] reveals realities what today's politicians refuse to face. In his recent summary of criminological and sociological research on long-term homicide rates, Yale legal scholar Dan Kahan found that U.S. homicide trends were directly tied both to alcohol prohibition in the 1920s and to the modern prohibition of drugs like marijuana and cocaine:

The weight of the evidence pretty convincingly shows that drug-related homicides generated as a consequence of drug prohibition are tremendously high and account for much of the difference in the homicide rates in the U.S. and those in comparable liberal market societies.

Kahan explains that "the criminogenic properties of drug prohibition create both a demand for murder of one's competitors and a demand for guns to use for that purpose." In other words, gun homicides can be traced to the synergy between booming gun markets and flourishing illicit drug markets, because a high-stakes illegal economy requires "enforcement" outside the law through coercion and force.

Kahan tells In These Times that, as part of a broad dialogue on realistic policy approaches to gun homicide, "our society ought to examine the ways in which our current drug-regulation policies themselves generate the sort of violence characteristic of black markets."

Certainly, Kahan's findings should complicate the public conversation. While simply legalizing or decriminalizing drugs won't necessarily end all the violence, an overhaul of drug policy seems a far more effective strategy to cut incentives for killing than the twisted lock-'em-up tactics of the last four decades.

Though just how best to change the system is debatable. Kahan suggests, "We could substantially reduce the number of gun homicides in our nation by reducing the emphasis on incarceration and strict crackdown-types of enforcement policies, and moving to some combination of legal markets and highly regulated public health alternatives to criminal law."

However, drug war violence in the U.S. must also be understood as one strain of a transnational epidemic of drug-related brutality. Globally, the drug business and the business of firearms are deeply intertwined. A 2010 Washington Post report details how U.S. guns have become a hot commodity at the border:

Drug cartels have aggressively turned to the United States because Mexico severely restricts gun ownership..... Federal authorities say more than 60,000 U.S. guns of all types have been recovered in Mexico in the past four years, helping fuel the violence that has contributed to 30,000 deaths.

Legal U.S. gun markets, which are sheltered by the gun industry's army of lobbyists, served as the interface for the Mexican black market in firearms that has played a role in many thousands of deaths, according to a 2009 analysis [PDF] by the Congressional Research Service:

Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) are increasingly sending enforcers across the border to hire surrogates (straw purchasers) who buy several 'military-style' firearms at a time from [federal firearms licensees].

Guns, bullets and body counts--all of which America produces in extreme numbers--don't tell the whole story of our violent culture, which is woven into the social structures we're taught to respect as emblems of "civilization." The drug war escalates the climate of violence through various forms, from the street, the state and the psychology of alienation and mistrust that it breeds. There is the mass incarceration that disproportionately impacts youth of color and their communities. Then there are innumerable casualties of draconian "border security" policies, which not only contribute to horrendous violent threats facing economic migrants, but also deepen the instability and oppression plaguing Latin American communities at the margins of Washington's garrison state.

The American brand of power operates through a continuum of warfare: from Pentagon drone targets to mass school shootings and neighborhood gang battles, and exported across the border to the blood-stained streets of Ciudad Juarez. Yet in the political arena, the boundaries of public compassion have tightened while the global scale of the casualties continually expands.Sandy Hook shocked the nation because of the seeming freakishness of its carnage, but what should truly alarm us about guns in America is the banality of the drug-war-fueled violence that enforces profound racial, economic and social divides. For all the divisions in how gun violence is experienced by different communities, we're all endangered by laws that erode humanity instead of securing it.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

When a hail of bullets extinguished dozens of lives at an elementary school last month, the ugly consequences of the nation's gun culture shot into the media spotlight. The debate around gun control in the aftermath of Newtown has yielded confused policy proposals like further militarizing schools, or preemptively tracking mentally ill people.

But a key aspect of the gun-control debate remains hiding in plain sight. There's a major driver of gun violence in the U.S. that is neither the bloodlust of the "criminally insane" nor the weakness of public security forces. Failed gun policy is a manifestation of another, arguably more expansive, irrational policy regime: the War on Drugs. While the most spectacular incidents of mass murder spark public panic, a more relevant, yet typically ignored, source of gun violence lies in the brutality born of the gun industry's marriage to drug prohibition policies.

For decades, the federal government has sought to eradicate drugs despite the utter futility of the effort and the devastating social, health and economic consequences of its tactics. While Sandy Hook triggered a national convulsion of disgust, the everyday casualties of the drug war have been met with relative silence. With annual gun homicides nationwide hovering around 10,000, a significant portion can be directly or indirectly linked to drug violence, though estimates for the death toll vary widely. (A recent CDC study of gang homicides, for example, notes that over 90 percent involve guns and the portion in different cities that were drug-related ranged from under five to about 25 percent.) Other analyses of national and international data likewise suggest a range of proportions depending on how drug-related killing is defined. Whatever the exact figure, the bottom line is that the drug war's institutionalized violence and oppression, fueled by "tough on crime" law enforcement, inflicts deep, needless social trauma on vulnerable communities. Underpinning that climate of violence are broader societal factors that also tend to be ignored in gun debates, including class and racial polarization.

Such tragedies seem worlds away from Newtown's massacre-perhaps because we've been sensitized over the years to accept the drug prohibition as a social imperative. In reality, the nation's enormously costly and destructive drug war greases the mechanics of our "culture" of gun violence, as much of the institutionalized violence is bound up with a policy regime that causes systematic harm in the name of public "safety."

Historical data [PDF] reveals realities what today's politicians refuse to face. In his recent summary of criminological and sociological research on long-term homicide rates, Yale legal scholar Dan Kahan found that U.S. homicide trends were directly tied both to alcohol prohibition in the 1920s and to the modern prohibition of drugs like marijuana and cocaine:

The weight of the evidence pretty convincingly shows that drug-related homicides generated as a consequence of drug prohibition are tremendously high and account for much of the difference in the homicide rates in the U.S. and those in comparable liberal market societies.

Kahan explains that "the criminogenic properties of drug prohibition create both a demand for murder of one's competitors and a demand for guns to use for that purpose." In other words, gun homicides can be traced to the synergy between booming gun markets and flourishing illicit drug markets, because a high-stakes illegal economy requires "enforcement" outside the law through coercion and force.

Kahan tells In These Times that, as part of a broad dialogue on realistic policy approaches to gun homicide, "our society ought to examine the ways in which our current drug-regulation policies themselves generate the sort of violence characteristic of black markets."

Certainly, Kahan's findings should complicate the public conversation. While simply legalizing or decriminalizing drugs won't necessarily end all the violence, an overhaul of drug policy seems a far more effective strategy to cut incentives for killing than the twisted lock-'em-up tactics of the last four decades.

Though just how best to change the system is debatable. Kahan suggests, "We could substantially reduce the number of gun homicides in our nation by reducing the emphasis on incarceration and strict crackdown-types of enforcement policies, and moving to some combination of legal markets and highly regulated public health alternatives to criminal law."

However, drug war violence in the U.S. must also be understood as one strain of a transnational epidemic of drug-related brutality. Globally, the drug business and the business of firearms are deeply intertwined. A 2010 Washington Post report details how U.S. guns have become a hot commodity at the border:

Drug cartels have aggressively turned to the United States because Mexico severely restricts gun ownership..... Federal authorities say more than 60,000 U.S. guns of all types have been recovered in Mexico in the past four years, helping fuel the violence that has contributed to 30,000 deaths.

Legal U.S. gun markets, which are sheltered by the gun industry's army of lobbyists, served as the interface for the Mexican black market in firearms that has played a role in many thousands of deaths, according to a 2009 analysis [PDF] by the Congressional Research Service:

Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) are increasingly sending enforcers across the border to hire surrogates (straw purchasers) who buy several 'military-style' firearms at a time from [federal firearms licensees].

Guns, bullets and body counts--all of which America produces in extreme numbers--don't tell the whole story of our violent culture, which is woven into the social structures we're taught to respect as emblems of "civilization." The drug war escalates the climate of violence through various forms, from the street, the state and the psychology of alienation and mistrust that it breeds. There is the mass incarceration that disproportionately impacts youth of color and their communities. Then there are innumerable casualties of draconian "border security" policies, which not only contribute to horrendous violent threats facing economic migrants, but also deepen the instability and oppression plaguing Latin American communities at the margins of Washington's garrison state.

The American brand of power operates through a continuum of warfare: from Pentagon drone targets to mass school shootings and neighborhood gang battles, and exported across the border to the blood-stained streets of Ciudad Juarez. Yet in the political arena, the boundaries of public compassion have tightened while the global scale of the casualties continually expands.Sandy Hook shocked the nation because of the seeming freakishness of its carnage, but what should truly alarm us about guns in America is the banality of the drug-war-fueled violence that enforces profound racial, economic and social divides. For all the divisions in how gun violence is experienced by different communities, we're all endangered by laws that erode humanity instead of securing it.

When a hail of bullets extinguished dozens of lives at an elementary school last month, the ugly consequences of the nation's gun culture shot into the media spotlight. The debate around gun control in the aftermath of Newtown has yielded confused policy proposals like further militarizing schools, or preemptively tracking mentally ill people.

But a key aspect of the gun-control debate remains hiding in plain sight. There's a major driver of gun violence in the U.S. that is neither the bloodlust of the "criminally insane" nor the weakness of public security forces. Failed gun policy is a manifestation of another, arguably more expansive, irrational policy regime: the War on Drugs. While the most spectacular incidents of mass murder spark public panic, a more relevant, yet typically ignored, source of gun violence lies in the brutality born of the gun industry's marriage to drug prohibition policies.

For decades, the federal government has sought to eradicate drugs despite the utter futility of the effort and the devastating social, health and economic consequences of its tactics. While Sandy Hook triggered a national convulsion of disgust, the everyday casualties of the drug war have been met with relative silence. With annual gun homicides nationwide hovering around 10,000, a significant portion can be directly or indirectly linked to drug violence, though estimates for the death toll vary widely. (A recent CDC study of gang homicides, for example, notes that over 90 percent involve guns and the portion in different cities that were drug-related ranged from under five to about 25 percent.) Other analyses of national and international data likewise suggest a range of proportions depending on how drug-related killing is defined. Whatever the exact figure, the bottom line is that the drug war's institutionalized violence and oppression, fueled by "tough on crime" law enforcement, inflicts deep, needless social trauma on vulnerable communities. Underpinning that climate of violence are broader societal factors that also tend to be ignored in gun debates, including class and racial polarization.

Such tragedies seem worlds away from Newtown's massacre-perhaps because we've been sensitized over the years to accept the drug prohibition as a social imperative. In reality, the nation's enormously costly and destructive drug war greases the mechanics of our "culture" of gun violence, as much of the institutionalized violence is bound up with a policy regime that causes systematic harm in the name of public "safety."

Historical data [PDF] reveals realities what today's politicians refuse to face. In his recent summary of criminological and sociological research on long-term homicide rates, Yale legal scholar Dan Kahan found that U.S. homicide trends were directly tied both to alcohol prohibition in the 1920s and to the modern prohibition of drugs like marijuana and cocaine:

The weight of the evidence pretty convincingly shows that drug-related homicides generated as a consequence of drug prohibition are tremendously high and account for much of the difference in the homicide rates in the U.S. and those in comparable liberal market societies.

Kahan explains that "the criminogenic properties of drug prohibition create both a demand for murder of one's competitors and a demand for guns to use for that purpose." In other words, gun homicides can be traced to the synergy between booming gun markets and flourishing illicit drug markets, because a high-stakes illegal economy requires "enforcement" outside the law through coercion and force.

Kahan tells In These Times that, as part of a broad dialogue on realistic policy approaches to gun homicide, "our society ought to examine the ways in which our current drug-regulation policies themselves generate the sort of violence characteristic of black markets."

Certainly, Kahan's findings should complicate the public conversation. While simply legalizing or decriminalizing drugs won't necessarily end all the violence, an overhaul of drug policy seems a far more effective strategy to cut incentives for killing than the twisted lock-'em-up tactics of the last four decades.

Though just how best to change the system is debatable. Kahan suggests, "We could substantially reduce the number of gun homicides in our nation by reducing the emphasis on incarceration and strict crackdown-types of enforcement policies, and moving to some combination of legal markets and highly regulated public health alternatives to criminal law."

However, drug war violence in the U.S. must also be understood as one strain of a transnational epidemic of drug-related brutality. Globally, the drug business and the business of firearms are deeply intertwined. A 2010 Washington Post report details how U.S. guns have become a hot commodity at the border:

Drug cartels have aggressively turned to the United States because Mexico severely restricts gun ownership..... Federal authorities say more than 60,000 U.S. guns of all types have been recovered in Mexico in the past four years, helping fuel the violence that has contributed to 30,000 deaths.

Legal U.S. gun markets, which are sheltered by the gun industry's army of lobbyists, served as the interface for the Mexican black market in firearms that has played a role in many thousands of deaths, according to a 2009 analysis [PDF] by the Congressional Research Service:

Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) are increasingly sending enforcers across the border to hire surrogates (straw purchasers) who buy several 'military-style' firearms at a time from [federal firearms licensees].

Guns, bullets and body counts--all of which America produces in extreme numbers--don't tell the whole story of our violent culture, which is woven into the social structures we're taught to respect as emblems of "civilization." The drug war escalates the climate of violence through various forms, from the street, the state and the psychology of alienation and mistrust that it breeds. There is the mass incarceration that disproportionately impacts youth of color and their communities. Then there are innumerable casualties of draconian "border security" policies, which not only contribute to horrendous violent threats facing economic migrants, but also deepen the instability and oppression plaguing Latin American communities at the margins of Washington's garrison state.

The American brand of power operates through a continuum of warfare: from Pentagon drone targets to mass school shootings and neighborhood gang battles, and exported across the border to the blood-stained streets of Ciudad Juarez. Yet in the political arena, the boundaries of public compassion have tightened while the global scale of the casualties continually expands.Sandy Hook shocked the nation because of the seeming freakishness of its carnage, but what should truly alarm us about guns in America is the banality of the drug-war-fueled violence that enforces profound racial, economic and social divides. For all the divisions in how gun violence is experienced by different communities, we're all endangered by laws that erode humanity instead of securing it.