Why Race Matters After Sandy

During the fall of 1962, residents of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn saw the trash accumulating on their sidewalks and realized that the city didn't care about them the way it did about others. Their children had to play in stinky garbage while other neighborhoods had trees and parks. They complained to elected officials and the Sanitation Department, but the problem never got better.

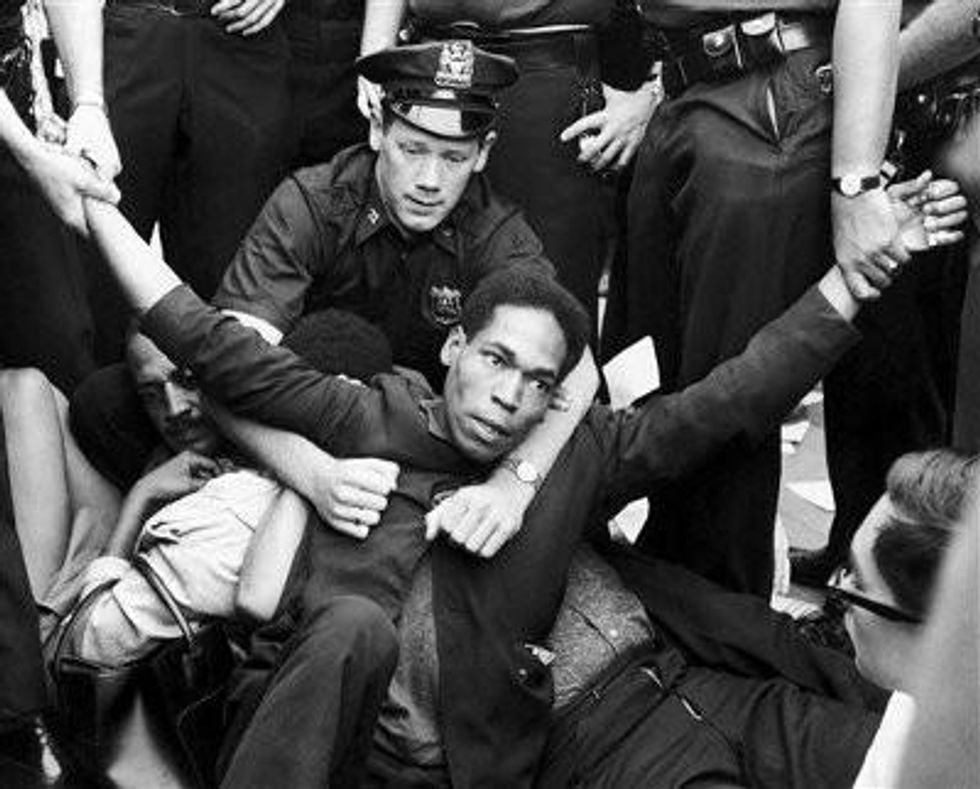

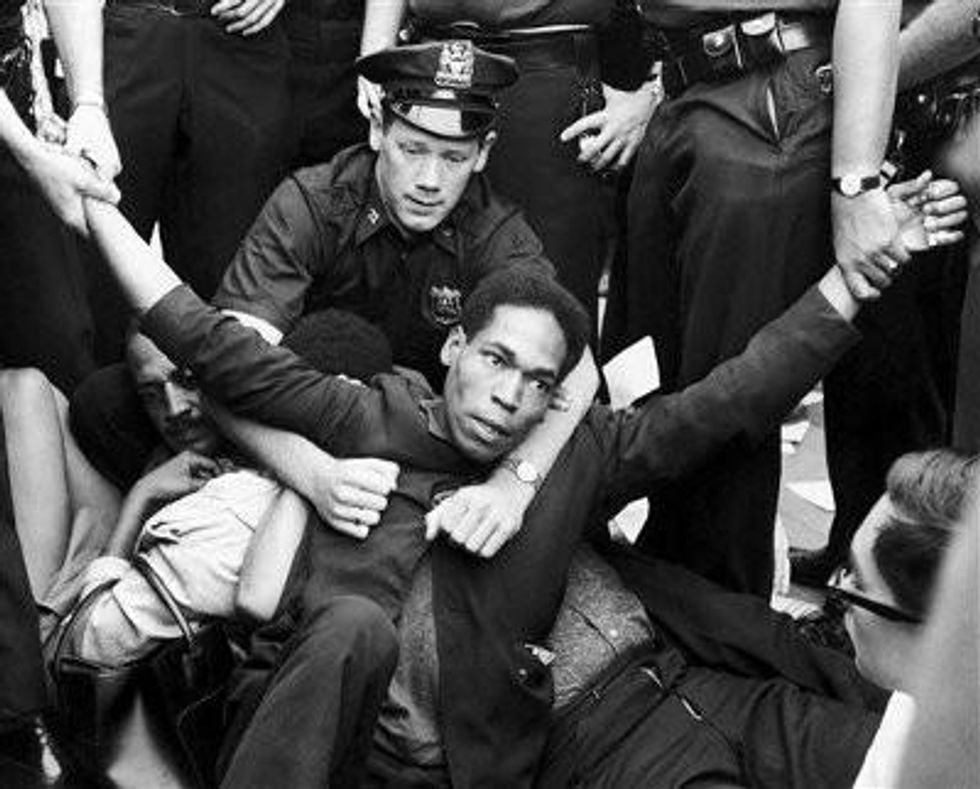

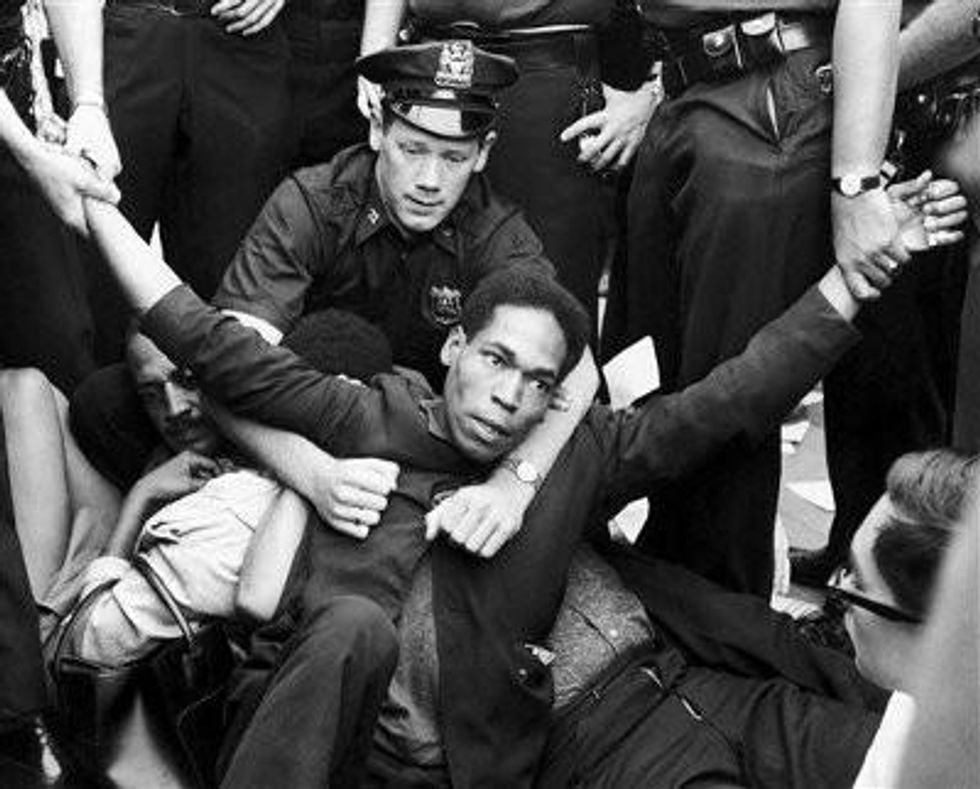

During the fall of 1962, residents of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn saw the trash accumulating on their sidewalks and realized that the city didn't care about them the way it did about others. Their children had to play in stinky garbage while other neighborhoods had trees and parks. They complained to elected officials and the Sanitation Department, but the problem never got better. So, in response, they began organizing weekly garbage clean-ups across Bed-Stuy -- a temporary solution -- while also working toward a holistic solution to the abundance of garbage and the scarcity of city resources devoted to the area through on-the-ground organizing. For two years residents and members of the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized tirelessly for increased garbage collection, asserting over and over again that "taxation without sanitation is tyranny."

For decades, the red-lining of black and brown neighborhoods by real estate agencies, banks and insurance companies has starved these communities of investment and served to geographically marginalize poor people. This history of economic and social marginalization helped ensure that these communities are also the ones hardest hit by disasters such as Hurricane Sandy. The challenge now facing Occupy Sandy and similar grassroots recovery efforts is to build community power around these structural inequalities through an environmental justice framework, while confronting environmental racism head on.

The concept of environmental racism emerged in the 1980s in East Harlem and the South Bronx as residents realized that their neighborhoods were home to waste processing plants that process over half of the city's commercial waste (in the case of the Bronx) and a disproportionate number of polluting bus depots (in the case of Harlem). These facilities were causing frequent illness, high rates of cancer and chronic asthma among children. Environmental racism gives a name to the harmful burden of facilities such as waste transplant stations, bus depots and power plants on communities where people of color tend to live.

This kind of analysis is important for two reasons. Firstly, it articulates that environmental factors are part of broader systematic disenfranchisement. Upper-middle class white neighborhoods are able to keep polluting facilities out while working-class neighborhoods of color get disproportionately saddled with this harmful infrastructure. Secondly, this analysis came from activists living and working in these neighborhoods, standing up against noxious facilities and clamoring for meaningful job opportunities, well-funded public schools, healthy and affordable food, and parks and other community spaces.

After Sandy, people in the affected communities are feeling the effects of this same phenomenon of environmental racism. Speaking to the Associated Press, one Staten Island resident, a Mexican immigrant named Miguel Alaracon Morales, explained, "My son has asthma and now he is worse. The house has this smell of humidity and sea water. It is not safe to live there. I am starting to feel sick, too." As he spoke, he held his two-year-old asthmatic son, Josias. This storm, and all disasters of its type, are not a "great equalizer," as is often claimed; they're actually only a disaster for the 99 percent, and in particular for the poorest and most disenfranchised members of our society.

In New York City's post-Sandy moment there are lessons to be learned from the community-led centers that emerged in New Orleans after Katrina. Our School at Blair Grocery, a community home-school and urban farm -- which Isabelle helped to establish and has spent every summer since 2008 working with -- is currently the only school that serves high school-aged youth and the only food vendor besides a corner store in the Lower Ninth Ward, whose population is down to 4,000 from over 14,000 before the storm. This independent alternative school confronts structural disenfranchisement by highlighting four main community needs: meaningful employment, healthy and affordable food, education for young people, and community-led public planning. Helping students earn their GEDs and avoid the school-to-prison pipeline, Our School at Blair Grocery works with black youth from the Lower Ninth with the long-term goal of building alternative institutions for the neighborhood that can withstand any crisis: economic, political and environmental.

In comparison to Occupy Sandy, "mutual aid" was not a term that was used in the context of New Orleans because it was seen as a contradiction -- outsider volunteers aiding residents was not "mutual" or egalitarian, per se. Many of the organizations that put racial justice at the center of their analysis instead endorsed the strategy of "bottom-up" organizing, which prioritizes the needs of poor people of color as those who are most affected by the disaster unveiled by Katrina. The environmental justice movement has always had "bottom-up" organizing at the center of its strategies -- mostly because few outside of these communities, who aren't suffering from asthma and high cancer rates, will fight against their root causes. Now in New York City, bottom-up organizing is needed again.

The community-led models of CORE and Our School at Blair Grocery demonstrate how to employ an analysis of environmental racism that takes into account the intersections of race, class, public planning and environmental degradation. Occupy Sandy's slogan "solidarity, not charity" is a starting point, but it doesn't go far enough in pushing allies from outside the most affected areas to understand how to avoid perpetuating the system they benefit from in recovery efforts. If we placed bottom-up organizing alongside mutual aid in our tools of recovery, it would mean organizers and volunteers taking direction from residents -- not only to get back on their feet but to transform their communities as they see fit.

In doing, we must also continue to practice direct action and make demands of city government. In 1962, after the city kept ignoring their demands, CORE organizers devised the campaign Operation Clean Sweep. Residents used brooms to sweep up the garbage left by the city on the side of the street, while CORE trucked the garbage to downtown Brooklyn and dumped it on the doorstep of Brooklyn's Borough Hall on September 15, 1962. CORE demanded a "First-Class Bedford-Stuyvesant Community" and "Integration with Better Sanitation." (Yotam Marom also told this story in his most recent article at Waging Nonviolence.)

Occupy Sandy needs to be not just another form of relief, or even recovery, but a force for social change that simultaneously works on a comprehensive strategy for community power. It needs to build infrastructure around housing, healthcare, food and energy sustainability that also make life easier for those most affected by environmental racism on a day-to-day basis. While protest should always be a part of our long-term strategy, we believe that Occupy Sandy must, to some extent, continue moving the solely protest-driven model adopted by Occupy Wall Street to embody movement practices led by communities.

This is already happening. While portrayals of Occupy Sandy in publications like The New York Times offer a depoliticized "feel-good relief" model of what is taking place, long-term strategy has been the goal since the beginning of the effort. "We were always thinking long-term," says Michael Premo, an Occupy Sandy organizer with experience in post-Katrina recovery. "Since day one we have been thinking about building a long-term grassroots resistance network that can win shit."

Learning from the organizing of CORE in Bed-Stuy in the 1960s, the environmental justice movement of the 1980s and post-Katrina models of alternative institution-building, we must realize that only through bottom-up, community-led structures can we confront systemic inequity in these neighborhoods. Doing this means taking on issues of privilege and racism, issues that Occupy Wall Street often has had trouble addressing. It means confronting supposed colorblindness and putting a racial justice analysis at the center of the analysis. This needs to happen in orientation trainings for volunteers, in organizing meetings, in our relationship-building with community leaders, in how aid is distributed, and in the physical gutting and rebuilding of people's homes.

We are making the road by walking right now. We have the paths left by past organizing models as reference points, but it is up to us to create the local solutions we need to address the global climate crisis in the midst of a racist society.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

During the fall of 1962, residents of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn saw the trash accumulating on their sidewalks and realized that the city didn't care about them the way it did about others. Their children had to play in stinky garbage while other neighborhoods had trees and parks. They complained to elected officials and the Sanitation Department, but the problem never got better. So, in response, they began organizing weekly garbage clean-ups across Bed-Stuy -- a temporary solution -- while also working toward a holistic solution to the abundance of garbage and the scarcity of city resources devoted to the area through on-the-ground organizing. For two years residents and members of the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized tirelessly for increased garbage collection, asserting over and over again that "taxation without sanitation is tyranny."

For decades, the red-lining of black and brown neighborhoods by real estate agencies, banks and insurance companies has starved these communities of investment and served to geographically marginalize poor people. This history of economic and social marginalization helped ensure that these communities are also the ones hardest hit by disasters such as Hurricane Sandy. The challenge now facing Occupy Sandy and similar grassroots recovery efforts is to build community power around these structural inequalities through an environmental justice framework, while confronting environmental racism head on.

The concept of environmental racism emerged in the 1980s in East Harlem and the South Bronx as residents realized that their neighborhoods were home to waste processing plants that process over half of the city's commercial waste (in the case of the Bronx) and a disproportionate number of polluting bus depots (in the case of Harlem). These facilities were causing frequent illness, high rates of cancer and chronic asthma among children. Environmental racism gives a name to the harmful burden of facilities such as waste transplant stations, bus depots and power plants on communities where people of color tend to live.

This kind of analysis is important for two reasons. Firstly, it articulates that environmental factors are part of broader systematic disenfranchisement. Upper-middle class white neighborhoods are able to keep polluting facilities out while working-class neighborhoods of color get disproportionately saddled with this harmful infrastructure. Secondly, this analysis came from activists living and working in these neighborhoods, standing up against noxious facilities and clamoring for meaningful job opportunities, well-funded public schools, healthy and affordable food, and parks and other community spaces.

After Sandy, people in the affected communities are feeling the effects of this same phenomenon of environmental racism. Speaking to the Associated Press, one Staten Island resident, a Mexican immigrant named Miguel Alaracon Morales, explained, "My son has asthma and now he is worse. The house has this smell of humidity and sea water. It is not safe to live there. I am starting to feel sick, too." As he spoke, he held his two-year-old asthmatic son, Josias. This storm, and all disasters of its type, are not a "great equalizer," as is often claimed; they're actually only a disaster for the 99 percent, and in particular for the poorest and most disenfranchised members of our society.

In New York City's post-Sandy moment there are lessons to be learned from the community-led centers that emerged in New Orleans after Katrina. Our School at Blair Grocery, a community home-school and urban farm -- which Isabelle helped to establish and has spent every summer since 2008 working with -- is currently the only school that serves high school-aged youth and the only food vendor besides a corner store in the Lower Ninth Ward, whose population is down to 4,000 from over 14,000 before the storm. This independent alternative school confronts structural disenfranchisement by highlighting four main community needs: meaningful employment, healthy and affordable food, education for young people, and community-led public planning. Helping students earn their GEDs and avoid the school-to-prison pipeline, Our School at Blair Grocery works with black youth from the Lower Ninth with the long-term goal of building alternative institutions for the neighborhood that can withstand any crisis: economic, political and environmental.

In comparison to Occupy Sandy, "mutual aid" was not a term that was used in the context of New Orleans because it was seen as a contradiction -- outsider volunteers aiding residents was not "mutual" or egalitarian, per se. Many of the organizations that put racial justice at the center of their analysis instead endorsed the strategy of "bottom-up" organizing, which prioritizes the needs of poor people of color as those who are most affected by the disaster unveiled by Katrina. The environmental justice movement has always had "bottom-up" organizing at the center of its strategies -- mostly because few outside of these communities, who aren't suffering from asthma and high cancer rates, will fight against their root causes. Now in New York City, bottom-up organizing is needed again.

The community-led models of CORE and Our School at Blair Grocery demonstrate how to employ an analysis of environmental racism that takes into account the intersections of race, class, public planning and environmental degradation. Occupy Sandy's slogan "solidarity, not charity" is a starting point, but it doesn't go far enough in pushing allies from outside the most affected areas to understand how to avoid perpetuating the system they benefit from in recovery efforts. If we placed bottom-up organizing alongside mutual aid in our tools of recovery, it would mean organizers and volunteers taking direction from residents -- not only to get back on their feet but to transform their communities as they see fit.

In doing, we must also continue to practice direct action and make demands of city government. In 1962, after the city kept ignoring their demands, CORE organizers devised the campaign Operation Clean Sweep. Residents used brooms to sweep up the garbage left by the city on the side of the street, while CORE trucked the garbage to downtown Brooklyn and dumped it on the doorstep of Brooklyn's Borough Hall on September 15, 1962. CORE demanded a "First-Class Bedford-Stuyvesant Community" and "Integration with Better Sanitation." (Yotam Marom also told this story in his most recent article at Waging Nonviolence.)

Occupy Sandy needs to be not just another form of relief, or even recovery, but a force for social change that simultaneously works on a comprehensive strategy for community power. It needs to build infrastructure around housing, healthcare, food and energy sustainability that also make life easier for those most affected by environmental racism on a day-to-day basis. While protest should always be a part of our long-term strategy, we believe that Occupy Sandy must, to some extent, continue moving the solely protest-driven model adopted by Occupy Wall Street to embody movement practices led by communities.

This is already happening. While portrayals of Occupy Sandy in publications like The New York Times offer a depoliticized "feel-good relief" model of what is taking place, long-term strategy has been the goal since the beginning of the effort. "We were always thinking long-term," says Michael Premo, an Occupy Sandy organizer with experience in post-Katrina recovery. "Since day one we have been thinking about building a long-term grassroots resistance network that can win shit."

Learning from the organizing of CORE in Bed-Stuy in the 1960s, the environmental justice movement of the 1980s and post-Katrina models of alternative institution-building, we must realize that only through bottom-up, community-led structures can we confront systemic inequity in these neighborhoods. Doing this means taking on issues of privilege and racism, issues that Occupy Wall Street often has had trouble addressing. It means confronting supposed colorblindness and putting a racial justice analysis at the center of the analysis. This needs to happen in orientation trainings for volunteers, in organizing meetings, in our relationship-building with community leaders, in how aid is distributed, and in the physical gutting and rebuilding of people's homes.

We are making the road by walking right now. We have the paths left by past organizing models as reference points, but it is up to us to create the local solutions we need to address the global climate crisis in the midst of a racist society.

During the fall of 1962, residents of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn saw the trash accumulating on their sidewalks and realized that the city didn't care about them the way it did about others. Their children had to play in stinky garbage while other neighborhoods had trees and parks. They complained to elected officials and the Sanitation Department, but the problem never got better. So, in response, they began organizing weekly garbage clean-ups across Bed-Stuy -- a temporary solution -- while also working toward a holistic solution to the abundance of garbage and the scarcity of city resources devoted to the area through on-the-ground organizing. For two years residents and members of the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized tirelessly for increased garbage collection, asserting over and over again that "taxation without sanitation is tyranny."

For decades, the red-lining of black and brown neighborhoods by real estate agencies, banks and insurance companies has starved these communities of investment and served to geographically marginalize poor people. This history of economic and social marginalization helped ensure that these communities are also the ones hardest hit by disasters such as Hurricane Sandy. The challenge now facing Occupy Sandy and similar grassroots recovery efforts is to build community power around these structural inequalities through an environmental justice framework, while confronting environmental racism head on.

The concept of environmental racism emerged in the 1980s in East Harlem and the South Bronx as residents realized that their neighborhoods were home to waste processing plants that process over half of the city's commercial waste (in the case of the Bronx) and a disproportionate number of polluting bus depots (in the case of Harlem). These facilities were causing frequent illness, high rates of cancer and chronic asthma among children. Environmental racism gives a name to the harmful burden of facilities such as waste transplant stations, bus depots and power plants on communities where people of color tend to live.

This kind of analysis is important for two reasons. Firstly, it articulates that environmental factors are part of broader systematic disenfranchisement. Upper-middle class white neighborhoods are able to keep polluting facilities out while working-class neighborhoods of color get disproportionately saddled with this harmful infrastructure. Secondly, this analysis came from activists living and working in these neighborhoods, standing up against noxious facilities and clamoring for meaningful job opportunities, well-funded public schools, healthy and affordable food, and parks and other community spaces.

After Sandy, people in the affected communities are feeling the effects of this same phenomenon of environmental racism. Speaking to the Associated Press, one Staten Island resident, a Mexican immigrant named Miguel Alaracon Morales, explained, "My son has asthma and now he is worse. The house has this smell of humidity and sea water. It is not safe to live there. I am starting to feel sick, too." As he spoke, he held his two-year-old asthmatic son, Josias. This storm, and all disasters of its type, are not a "great equalizer," as is often claimed; they're actually only a disaster for the 99 percent, and in particular for the poorest and most disenfranchised members of our society.

In New York City's post-Sandy moment there are lessons to be learned from the community-led centers that emerged in New Orleans after Katrina. Our School at Blair Grocery, a community home-school and urban farm -- which Isabelle helped to establish and has spent every summer since 2008 working with -- is currently the only school that serves high school-aged youth and the only food vendor besides a corner store in the Lower Ninth Ward, whose population is down to 4,000 from over 14,000 before the storm. This independent alternative school confronts structural disenfranchisement by highlighting four main community needs: meaningful employment, healthy and affordable food, education for young people, and community-led public planning. Helping students earn their GEDs and avoid the school-to-prison pipeline, Our School at Blair Grocery works with black youth from the Lower Ninth with the long-term goal of building alternative institutions for the neighborhood that can withstand any crisis: economic, political and environmental.

In comparison to Occupy Sandy, "mutual aid" was not a term that was used in the context of New Orleans because it was seen as a contradiction -- outsider volunteers aiding residents was not "mutual" or egalitarian, per se. Many of the organizations that put racial justice at the center of their analysis instead endorsed the strategy of "bottom-up" organizing, which prioritizes the needs of poor people of color as those who are most affected by the disaster unveiled by Katrina. The environmental justice movement has always had "bottom-up" organizing at the center of its strategies -- mostly because few outside of these communities, who aren't suffering from asthma and high cancer rates, will fight against their root causes. Now in New York City, bottom-up organizing is needed again.

The community-led models of CORE and Our School at Blair Grocery demonstrate how to employ an analysis of environmental racism that takes into account the intersections of race, class, public planning and environmental degradation. Occupy Sandy's slogan "solidarity, not charity" is a starting point, but it doesn't go far enough in pushing allies from outside the most affected areas to understand how to avoid perpetuating the system they benefit from in recovery efforts. If we placed bottom-up organizing alongside mutual aid in our tools of recovery, it would mean organizers and volunteers taking direction from residents -- not only to get back on their feet but to transform their communities as they see fit.

In doing, we must also continue to practice direct action and make demands of city government. In 1962, after the city kept ignoring their demands, CORE organizers devised the campaign Operation Clean Sweep. Residents used brooms to sweep up the garbage left by the city on the side of the street, while CORE trucked the garbage to downtown Brooklyn and dumped it on the doorstep of Brooklyn's Borough Hall on September 15, 1962. CORE demanded a "First-Class Bedford-Stuyvesant Community" and "Integration with Better Sanitation." (Yotam Marom also told this story in his most recent article at Waging Nonviolence.)

Occupy Sandy needs to be not just another form of relief, or even recovery, but a force for social change that simultaneously works on a comprehensive strategy for community power. It needs to build infrastructure around housing, healthcare, food and energy sustainability that also make life easier for those most affected by environmental racism on a day-to-day basis. While protest should always be a part of our long-term strategy, we believe that Occupy Sandy must, to some extent, continue moving the solely protest-driven model adopted by Occupy Wall Street to embody movement practices led by communities.

This is already happening. While portrayals of Occupy Sandy in publications like The New York Times offer a depoliticized "feel-good relief" model of what is taking place, long-term strategy has been the goal since the beginning of the effort. "We were always thinking long-term," says Michael Premo, an Occupy Sandy organizer with experience in post-Katrina recovery. "Since day one we have been thinking about building a long-term grassroots resistance network that can win shit."

Learning from the organizing of CORE in Bed-Stuy in the 1960s, the environmental justice movement of the 1980s and post-Katrina models of alternative institution-building, we must realize that only through bottom-up, community-led structures can we confront systemic inequity in these neighborhoods. Doing this means taking on issues of privilege and racism, issues that Occupy Wall Street often has had trouble addressing. It means confronting supposed colorblindness and putting a racial justice analysis at the center of the analysis. This needs to happen in orientation trainings for volunteers, in organizing meetings, in our relationship-building with community leaders, in how aid is distributed, and in the physical gutting and rebuilding of people's homes.

We are making the road by walking right now. We have the paths left by past organizing models as reference points, but it is up to us to create the local solutions we need to address the global climate crisis in the midst of a racist society.