World Bank's Anti-Labor Index Is a Dirty Business

It's a 2012 campaign mantra: On Day One, the new president will reboot the economy by spurring businesses to grow and thrive.

The story is surprisingly similar across the pond. The financial giants of Europe's troika pummel Greece and other struggling Eurozone countries with a blitzkrieg of kamikaze deregulation, conditioning financial "rescue" on giving markets free rein to work their magic, unencumbered by law. The flipside of this celebration of the Invisible Hand is, inevitably, a merciless beatdown on labor, stripping protections like unemployment aid and wage standards.

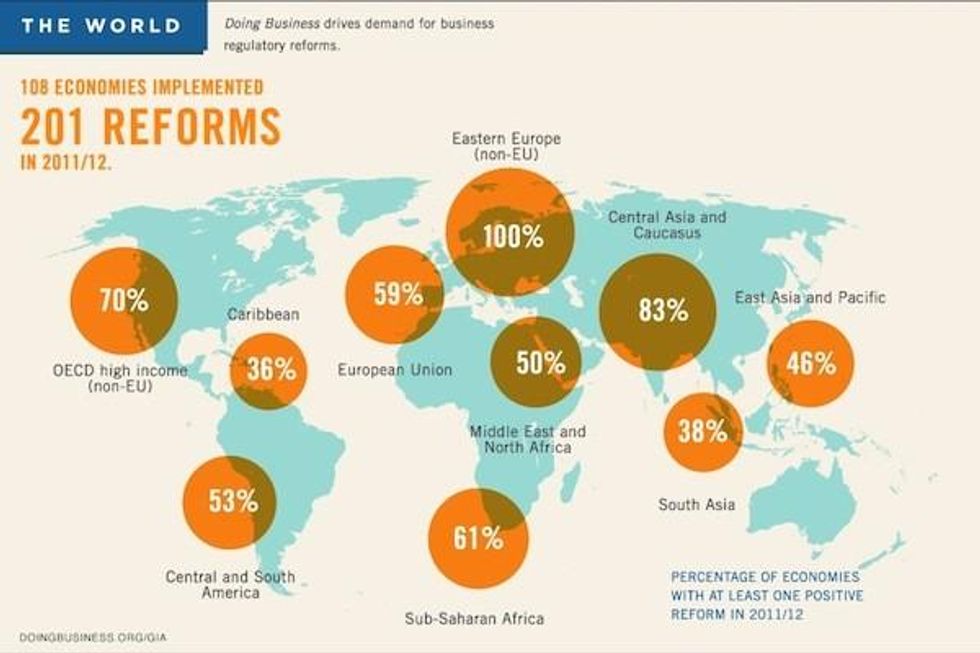

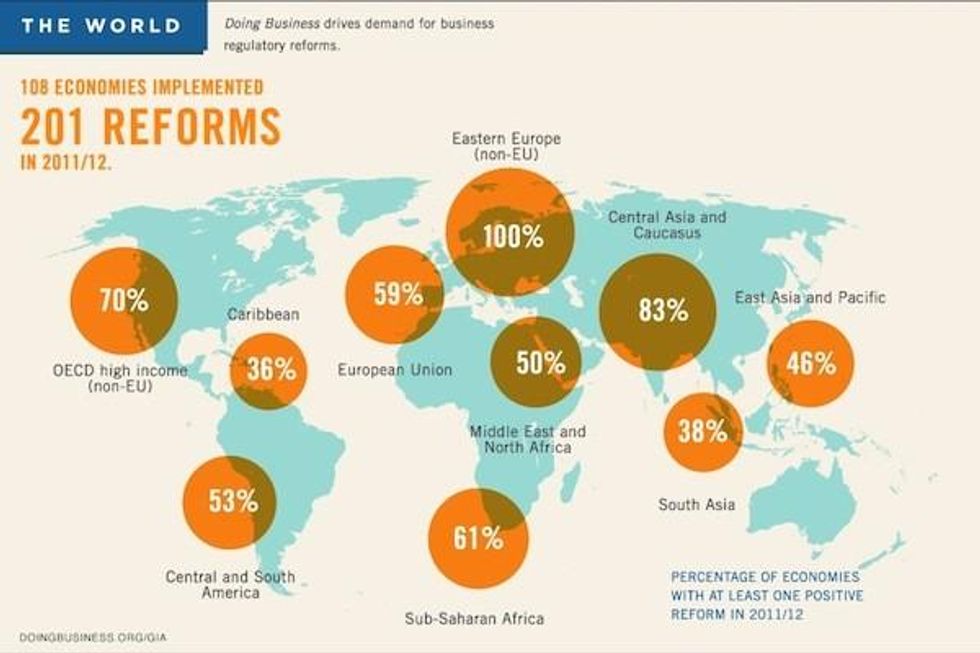

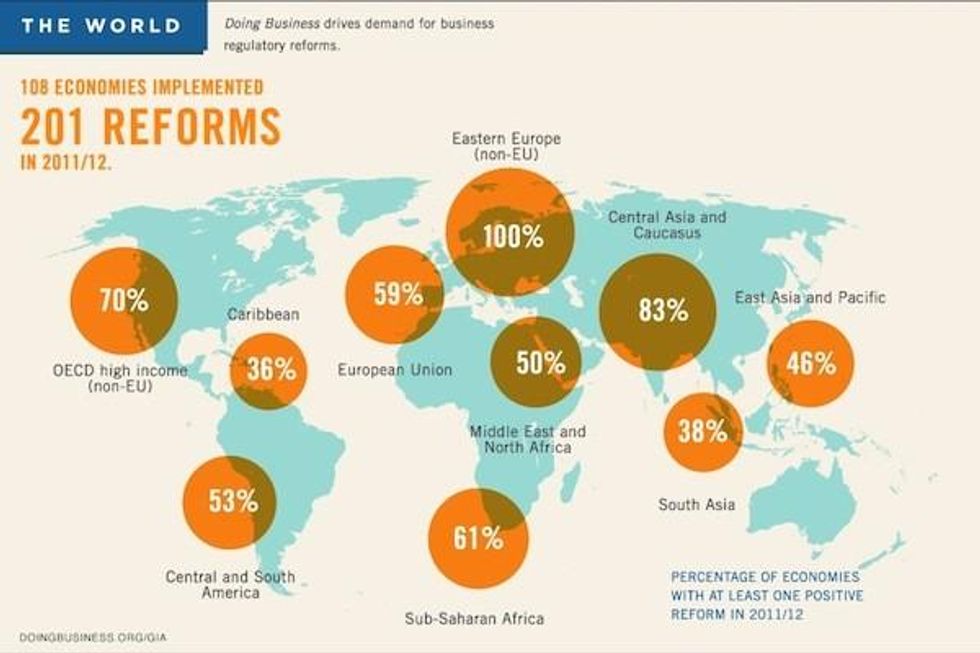

The World Bank has taken the extremely dubious science of deregulation one step further by creating a guide, known as the Doing Business report, that quantifies the regulatory "burden" that investors may face in various countries. The 2013 report was released this week.

Echoing the corporate "job creator" mythology of the Washington consensus, Doing Business encourages financiers and governments to erode public-interest protections, including safeguards for unions and workers. Labor groups say the publication's warped views on regulation and worker protections effectively gives a statistical justification for leveraging economic aid or investment to pressure countries to privatize, deregulate and undermine unions.

Labor advocates are particularly critical of the section of the report that crystallizes these views, the "Employing Workers Indicator" (EWI) which purports to measure labor policy "as it affects the hiring and redundancy of workers and the rigidity of working hours." Despite the World Bank's past assurances that its analysis of labor regulations won't factor into the main rankings on business friendliness, critics fear that these data nonetheless filter into the report's evaluations, and in turn imply labor laws essentially impede development.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) criticizes the 2013 report's implicit endorsement of policies that slash benefits for laid-off workers, which praises governments for "addressing one of the main factors deterring employers from creating jobs in the formal sector." Similarly, the report chastises some countries in Africa for granting supposedly over-generous severance-pay requirements for displaced workers, while ignoring the fact that severance pay is especially vital for workers in weaker economies because, in contrast to wealthier regions, "state-provided unemployment benefits are practically non-existent."

From an empirical standpoint, the labor analyses in the Employing Workers section has historically invoked fuzzy math. Previous editions have given high marks to governments notorious for hostility to labor rights (what neoliberals call "flexibility"), and criticized other countries, like Brazil and South Korea, for their labor "rigidity," even though they had made significant progress in both poverty reduction and economic development. In recent years, ITUC argues, this skewed rational has been used to support cutbacks on labor protections in Greece, Mozambique, Jordan and other countries. In the current global economic crisis, we're now witnessing the chaotic consequences of earlier waves of deregulation.

In 2009, under pressure from labor advocates such as the International Labour Organisation, the World Bank shifted its stance and declared that the index "should not be used as a basis for policy advice or in any country program documents that outline or evaluate the development strategy or assistance program for a recipient country."

Yet the anti-regulatory sentiment within Doing Business and the EWI continued to inform some policy discussions. For example, according to ITUC's research, Doing Business was cited in a 2010 IMF analysis of Romania, which has been supported by IMF financing, to push the government "to increase working time flexibility and to reduce hiring and firing costs."

Calling the notion that labor standards drag down the economy a "totally lopsided" framework, Peter Bakvis, director of ITUC's Washington Office, told Working In These Times: "To have the World Bank's highest circulation publication present this very unilateral view, which is not based on evidence, that countries that do away with labor regulations will get more investment and more growth, is very harmful." Rather than focusing on further empowering corporations, he added, "The bank should be encouraging countries to adopt policies that share growth as best as possible, that protect workers who are threatened by job loss."

It's not just poor countries that are affected by these neoliberal economic assessments. The same morally bankrupt cost-benefit analyses filter into U.S. politics in campaigns to strip away crucial protections such as collective bargaining rights and anti-discrimination fair-pay laws. Whether regulation aims to ensure safety standards at workplaces or limit air pollution or keep people from being arbitrarily fired, none of it is viewed by Washington neoliberals as protection for the vulnerable, but rather, as an assault on free enterprise.

Of course, neoliberal policies would continue steamrolling the poor with or without the Doing Business indices, but the World Bank's arbitrary assessments lend a dangerous veneer of objectivity to political attacks on working people and unions. This is the arithmetic of unfettered business: Add capital, subtract rights, and the 99% wind up with nothing.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The story is surprisingly similar across the pond. The financial giants of Europe's troika pummel Greece and other struggling Eurozone countries with a blitzkrieg of kamikaze deregulation, conditioning financial "rescue" on giving markets free rein to work their magic, unencumbered by law. The flipside of this celebration of the Invisible Hand is, inevitably, a merciless beatdown on labor, stripping protections like unemployment aid and wage standards.

The World Bank has taken the extremely dubious science of deregulation one step further by creating a guide, known as the Doing Business report, that quantifies the regulatory "burden" that investors may face in various countries. The 2013 report was released this week.

Echoing the corporate "job creator" mythology of the Washington consensus, Doing Business encourages financiers and governments to erode public-interest protections, including safeguards for unions and workers. Labor groups say the publication's warped views on regulation and worker protections effectively gives a statistical justification for leveraging economic aid or investment to pressure countries to privatize, deregulate and undermine unions.

Labor advocates are particularly critical of the section of the report that crystallizes these views, the "Employing Workers Indicator" (EWI) which purports to measure labor policy "as it affects the hiring and redundancy of workers and the rigidity of working hours." Despite the World Bank's past assurances that its analysis of labor regulations won't factor into the main rankings on business friendliness, critics fear that these data nonetheless filter into the report's evaluations, and in turn imply labor laws essentially impede development.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) criticizes the 2013 report's implicit endorsement of policies that slash benefits for laid-off workers, which praises governments for "addressing one of the main factors deterring employers from creating jobs in the formal sector." Similarly, the report chastises some countries in Africa for granting supposedly over-generous severance-pay requirements for displaced workers, while ignoring the fact that severance pay is especially vital for workers in weaker economies because, in contrast to wealthier regions, "state-provided unemployment benefits are practically non-existent."

From an empirical standpoint, the labor analyses in the Employing Workers section has historically invoked fuzzy math. Previous editions have given high marks to governments notorious for hostility to labor rights (what neoliberals call "flexibility"), and criticized other countries, like Brazil and South Korea, for their labor "rigidity," even though they had made significant progress in both poverty reduction and economic development. In recent years, ITUC argues, this skewed rational has been used to support cutbacks on labor protections in Greece, Mozambique, Jordan and other countries. In the current global economic crisis, we're now witnessing the chaotic consequences of earlier waves of deregulation.

In 2009, under pressure from labor advocates such as the International Labour Organisation, the World Bank shifted its stance and declared that the index "should not be used as a basis for policy advice or in any country program documents that outline or evaluate the development strategy or assistance program for a recipient country."

Yet the anti-regulatory sentiment within Doing Business and the EWI continued to inform some policy discussions. For example, according to ITUC's research, Doing Business was cited in a 2010 IMF analysis of Romania, which has been supported by IMF financing, to push the government "to increase working time flexibility and to reduce hiring and firing costs."

Calling the notion that labor standards drag down the economy a "totally lopsided" framework, Peter Bakvis, director of ITUC's Washington Office, told Working In These Times: "To have the World Bank's highest circulation publication present this very unilateral view, which is not based on evidence, that countries that do away with labor regulations will get more investment and more growth, is very harmful." Rather than focusing on further empowering corporations, he added, "The bank should be encouraging countries to adopt policies that share growth as best as possible, that protect workers who are threatened by job loss."

It's not just poor countries that are affected by these neoliberal economic assessments. The same morally bankrupt cost-benefit analyses filter into U.S. politics in campaigns to strip away crucial protections such as collective bargaining rights and anti-discrimination fair-pay laws. Whether regulation aims to ensure safety standards at workplaces or limit air pollution or keep people from being arbitrarily fired, none of it is viewed by Washington neoliberals as protection for the vulnerable, but rather, as an assault on free enterprise.

Of course, neoliberal policies would continue steamrolling the poor with or without the Doing Business indices, but the World Bank's arbitrary assessments lend a dangerous veneer of objectivity to political attacks on working people and unions. This is the arithmetic of unfettered business: Add capital, subtract rights, and the 99% wind up with nothing.

The story is surprisingly similar across the pond. The financial giants of Europe's troika pummel Greece and other struggling Eurozone countries with a blitzkrieg of kamikaze deregulation, conditioning financial "rescue" on giving markets free rein to work their magic, unencumbered by law. The flipside of this celebration of the Invisible Hand is, inevitably, a merciless beatdown on labor, stripping protections like unemployment aid and wage standards.

The World Bank has taken the extremely dubious science of deregulation one step further by creating a guide, known as the Doing Business report, that quantifies the regulatory "burden" that investors may face in various countries. The 2013 report was released this week.

Echoing the corporate "job creator" mythology of the Washington consensus, Doing Business encourages financiers and governments to erode public-interest protections, including safeguards for unions and workers. Labor groups say the publication's warped views on regulation and worker protections effectively gives a statistical justification for leveraging economic aid or investment to pressure countries to privatize, deregulate and undermine unions.

Labor advocates are particularly critical of the section of the report that crystallizes these views, the "Employing Workers Indicator" (EWI) which purports to measure labor policy "as it affects the hiring and redundancy of workers and the rigidity of working hours." Despite the World Bank's past assurances that its analysis of labor regulations won't factor into the main rankings on business friendliness, critics fear that these data nonetheless filter into the report's evaluations, and in turn imply labor laws essentially impede development.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) criticizes the 2013 report's implicit endorsement of policies that slash benefits for laid-off workers, which praises governments for "addressing one of the main factors deterring employers from creating jobs in the formal sector." Similarly, the report chastises some countries in Africa for granting supposedly over-generous severance-pay requirements for displaced workers, while ignoring the fact that severance pay is especially vital for workers in weaker economies because, in contrast to wealthier regions, "state-provided unemployment benefits are practically non-existent."

From an empirical standpoint, the labor analyses in the Employing Workers section has historically invoked fuzzy math. Previous editions have given high marks to governments notorious for hostility to labor rights (what neoliberals call "flexibility"), and criticized other countries, like Brazil and South Korea, for their labor "rigidity," even though they had made significant progress in both poverty reduction and economic development. In recent years, ITUC argues, this skewed rational has been used to support cutbacks on labor protections in Greece, Mozambique, Jordan and other countries. In the current global economic crisis, we're now witnessing the chaotic consequences of earlier waves of deregulation.

In 2009, under pressure from labor advocates such as the International Labour Organisation, the World Bank shifted its stance and declared that the index "should not be used as a basis for policy advice or in any country program documents that outline or evaluate the development strategy or assistance program for a recipient country."

Yet the anti-regulatory sentiment within Doing Business and the EWI continued to inform some policy discussions. For example, according to ITUC's research, Doing Business was cited in a 2010 IMF analysis of Romania, which has been supported by IMF financing, to push the government "to increase working time flexibility and to reduce hiring and firing costs."

Calling the notion that labor standards drag down the economy a "totally lopsided" framework, Peter Bakvis, director of ITUC's Washington Office, told Working In These Times: "To have the World Bank's highest circulation publication present this very unilateral view, which is not based on evidence, that countries that do away with labor regulations will get more investment and more growth, is very harmful." Rather than focusing on further empowering corporations, he added, "The bank should be encouraging countries to adopt policies that share growth as best as possible, that protect workers who are threatened by job loss."

It's not just poor countries that are affected by these neoliberal economic assessments. The same morally bankrupt cost-benefit analyses filter into U.S. politics in campaigns to strip away crucial protections such as collective bargaining rights and anti-discrimination fair-pay laws. Whether regulation aims to ensure safety standards at workplaces or limit air pollution or keep people from being arbitrarily fired, none of it is viewed by Washington neoliberals as protection for the vulnerable, but rather, as an assault on free enterprise.

Of course, neoliberal policies would continue steamrolling the poor with or without the Doing Business indices, but the World Bank's arbitrary assessments lend a dangerous veneer of objectivity to political attacks on working people and unions. This is the arithmetic of unfettered business: Add capital, subtract rights, and the 99% wind up with nothing.