A Bold New Call for a 'Maximum Wage'

A national labor leader aims to expand the economic fairness debate.

How about taking a moment this Labor Day to reflect about those Americans who earn the least for their labor?

These Americans -- workers paid the federal minimum wage -- are now making $7.25 an hour. On paper, they're making the same wage they made in July 2009, the last time we saw the minimum wage change. In reality, minimum-wage workers are making less today than they made last year because inflation has eaten away at their incomes.

Minimum-wage workers here in 2012 simply can't purchase as much with their paychecks as they could in 2011. And if you go back a few decades, today's raw deal gets even rawer. Back in 1968, minimum-wage workers took home $1.60 an hour. To make that much today, adjusting for inflation, a minimum-wage worker would have to earn $10.55 an hour.

In effect, minimum-wage workers today are taking home almost $7,000 less a year than minimum-wage workers took home in 1968.

Figures like these don't particularly upset many of our nation's most powerful, in either industry or government. We live in tough times, the argument goes. The small businesses that drive our economy simply can't afford to pay their help any more than they already do.

But the vast majority of our nation's minimum-wage workers don't labor for Main Street mom-and-pops. They're employed by businesses that no average American would ever call small. Two-thirds of America's low-wage workers, the National Employment Law Project documented in July, work for companies that have at least 100 employees.

The 50 largest of these low-wage employers are doing just fine these days. Over the last five years, these 50 corporations -- outfits that range from Walmart to Office Depot -- have together returned $175 billion to shareholders in dividends or share buybacks.

And the CEOs at these companies last year averaged $9.4 million in personal compensation. A minimum-wage worker would have to labor 623 years to bring in that much money.

So what can we do to bring some semblance of fairness back into our workplaces? For starters, we obviously need to raise the minimum wage. But some close observers of America's economic landscape believe we need to do more. A great deal more.

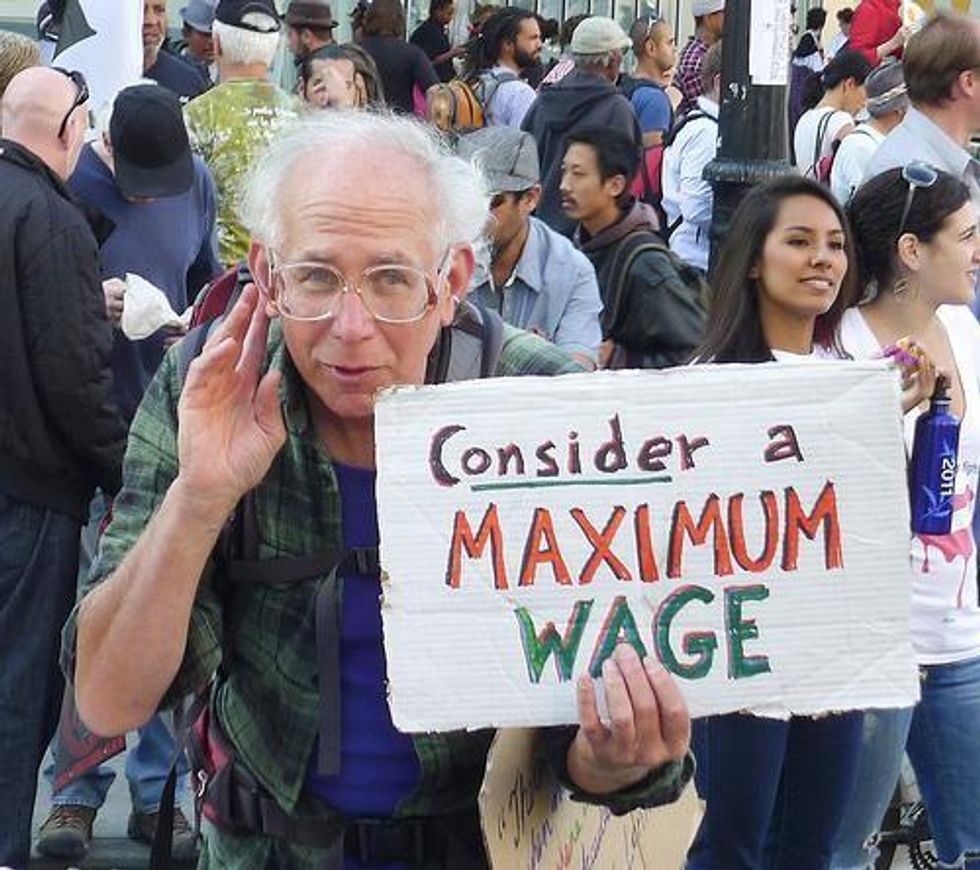

Count Larry Hanley among these more ambitious change agents. Hanley, the president of the Amalgamated Transit Union, sits on the AFL-CIO's executive council, the labor movement's top decision-making body. He recently called for a "maximum wage," a cap on the compensation that goes to the corporate execs who profit so hugely off low-wage labor.

Hanley wants to see this maximum defined as a multiple of the pay that goes to a company's lowest-paid worker. If we had a "maximum wage" set at 100 times that lowest wage, the CEO of a company that paid some workers as low as $16,000 a year could waltz off with annual pay no higher than $1.6 million.

During World War II, labor leader Hanley points out, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for what amounted to a maximum wage. FDR urged Congress to place a 100-percent tax on income over $25,000 a year, a sum that would now equal, after inflation, just over $350,000.

Congress didn't go along. But FDR did end up winning a 94-percent top tax rate on income over $200,000, a move that would help usher in the greatest years of middle-class prosperity the United States has ever known.

Throughout World War II, FDR enjoyed broad support from within the labor movement -- and the general public -- for his pay cap notion. Now's the time, Hanley believes, to put that notion back on the political table. We need, he says, "to start a national discussion about creating a maximum wage law."

Hanley may just have started that discussion.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

How about taking a moment this Labor Day to reflect about those Americans who earn the least for their labor?

These Americans -- workers paid the federal minimum wage -- are now making $7.25 an hour. On paper, they're making the same wage they made in July 2009, the last time we saw the minimum wage change. In reality, minimum-wage workers are making less today than they made last year because inflation has eaten away at their incomes.

Minimum-wage workers here in 2012 simply can't purchase as much with their paychecks as they could in 2011. And if you go back a few decades, today's raw deal gets even rawer. Back in 1968, minimum-wage workers took home $1.60 an hour. To make that much today, adjusting for inflation, a minimum-wage worker would have to earn $10.55 an hour.

In effect, minimum-wage workers today are taking home almost $7,000 less a year than minimum-wage workers took home in 1968.

Figures like these don't particularly upset many of our nation's most powerful, in either industry or government. We live in tough times, the argument goes. The small businesses that drive our economy simply can't afford to pay their help any more than they already do.

But the vast majority of our nation's minimum-wage workers don't labor for Main Street mom-and-pops. They're employed by businesses that no average American would ever call small. Two-thirds of America's low-wage workers, the National Employment Law Project documented in July, work for companies that have at least 100 employees.

The 50 largest of these low-wage employers are doing just fine these days. Over the last five years, these 50 corporations -- outfits that range from Walmart to Office Depot -- have together returned $175 billion to shareholders in dividends or share buybacks.

And the CEOs at these companies last year averaged $9.4 million in personal compensation. A minimum-wage worker would have to labor 623 years to bring in that much money.

So what can we do to bring some semblance of fairness back into our workplaces? For starters, we obviously need to raise the minimum wage. But some close observers of America's economic landscape believe we need to do more. A great deal more.

Count Larry Hanley among these more ambitious change agents. Hanley, the president of the Amalgamated Transit Union, sits on the AFL-CIO's executive council, the labor movement's top decision-making body. He recently called for a "maximum wage," a cap on the compensation that goes to the corporate execs who profit so hugely off low-wage labor.

Hanley wants to see this maximum defined as a multiple of the pay that goes to a company's lowest-paid worker. If we had a "maximum wage" set at 100 times that lowest wage, the CEO of a company that paid some workers as low as $16,000 a year could waltz off with annual pay no higher than $1.6 million.

During World War II, labor leader Hanley points out, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for what amounted to a maximum wage. FDR urged Congress to place a 100-percent tax on income over $25,000 a year, a sum that would now equal, after inflation, just over $350,000.

Congress didn't go along. But FDR did end up winning a 94-percent top tax rate on income over $200,000, a move that would help usher in the greatest years of middle-class prosperity the United States has ever known.

Throughout World War II, FDR enjoyed broad support from within the labor movement -- and the general public -- for his pay cap notion. Now's the time, Hanley believes, to put that notion back on the political table. We need, he says, "to start a national discussion about creating a maximum wage law."

Hanley may just have started that discussion.

How about taking a moment this Labor Day to reflect about those Americans who earn the least for their labor?

These Americans -- workers paid the federal minimum wage -- are now making $7.25 an hour. On paper, they're making the same wage they made in July 2009, the last time we saw the minimum wage change. In reality, minimum-wage workers are making less today than they made last year because inflation has eaten away at their incomes.

Minimum-wage workers here in 2012 simply can't purchase as much with their paychecks as they could in 2011. And if you go back a few decades, today's raw deal gets even rawer. Back in 1968, minimum-wage workers took home $1.60 an hour. To make that much today, adjusting for inflation, a minimum-wage worker would have to earn $10.55 an hour.

In effect, minimum-wage workers today are taking home almost $7,000 less a year than minimum-wage workers took home in 1968.

Figures like these don't particularly upset many of our nation's most powerful, in either industry or government. We live in tough times, the argument goes. The small businesses that drive our economy simply can't afford to pay their help any more than they already do.

But the vast majority of our nation's minimum-wage workers don't labor for Main Street mom-and-pops. They're employed by businesses that no average American would ever call small. Two-thirds of America's low-wage workers, the National Employment Law Project documented in July, work for companies that have at least 100 employees.

The 50 largest of these low-wage employers are doing just fine these days. Over the last five years, these 50 corporations -- outfits that range from Walmart to Office Depot -- have together returned $175 billion to shareholders in dividends or share buybacks.

And the CEOs at these companies last year averaged $9.4 million in personal compensation. A minimum-wage worker would have to labor 623 years to bring in that much money.

So what can we do to bring some semblance of fairness back into our workplaces? For starters, we obviously need to raise the minimum wage. But some close observers of America's economic landscape believe we need to do more. A great deal more.

Count Larry Hanley among these more ambitious change agents. Hanley, the president of the Amalgamated Transit Union, sits on the AFL-CIO's executive council, the labor movement's top decision-making body. He recently called for a "maximum wage," a cap on the compensation that goes to the corporate execs who profit so hugely off low-wage labor.

Hanley wants to see this maximum defined as a multiple of the pay that goes to a company's lowest-paid worker. If we had a "maximum wage" set at 100 times that lowest wage, the CEO of a company that paid some workers as low as $16,000 a year could waltz off with annual pay no higher than $1.6 million.

During World War II, labor leader Hanley points out, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for what amounted to a maximum wage. FDR urged Congress to place a 100-percent tax on income over $25,000 a year, a sum that would now equal, after inflation, just over $350,000.

Congress didn't go along. But FDR did end up winning a 94-percent top tax rate on income over $200,000, a move that would help usher in the greatest years of middle-class prosperity the United States has ever known.

Throughout World War II, FDR enjoyed broad support from within the labor movement -- and the general public -- for his pay cap notion. Now's the time, Hanley believes, to put that notion back on the political table. We need, he says, "to start a national discussion about creating a maximum wage law."

Hanley may just have started that discussion.