SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

One hundred years after the birth of human rights icon Bayard Rustin, his complicated legacy pushes us to analyze our own complicated times. Vilified in the 1950s for his open homosexuality and again in the 1960s for "selling out" the radical black liberation movement, Rustin's own history has been recently rescued by the books and movie correctly extolling his incredible gifts as a grassroots organizer, a charismatic orator and a visionary thinker.

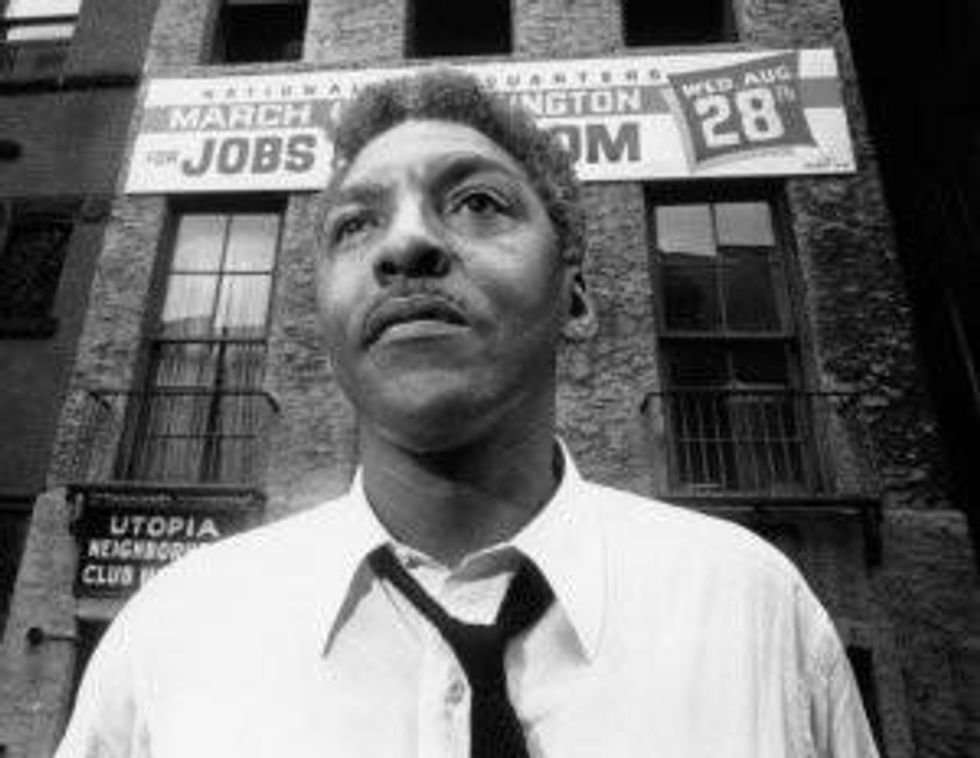

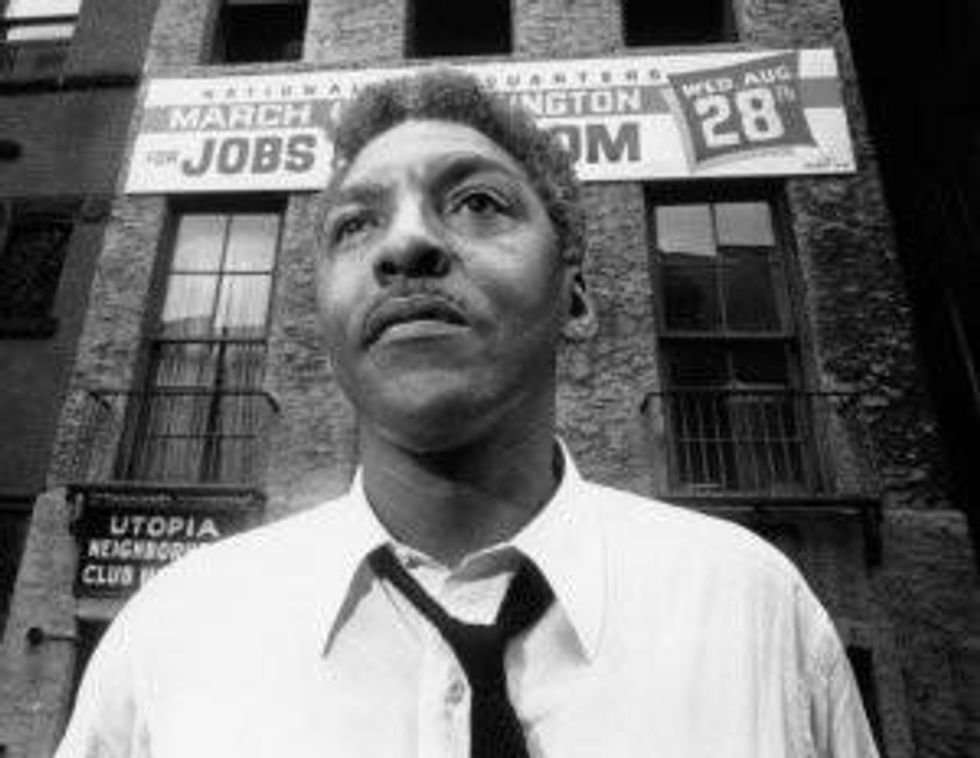

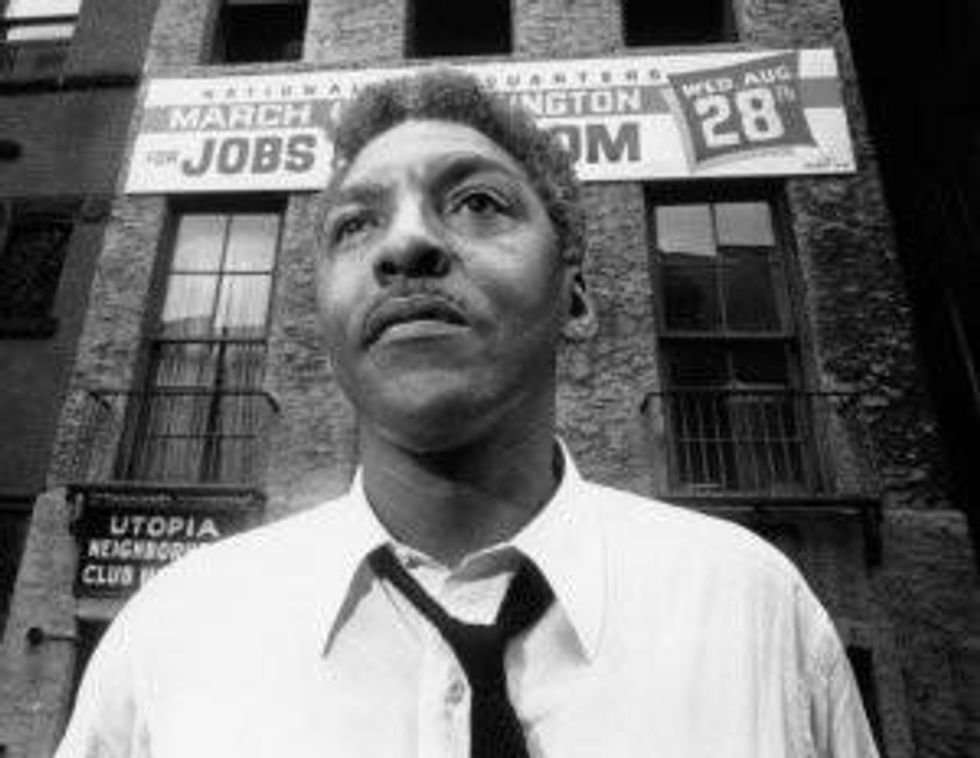

One hundred years after the birth of human rights icon Bayard Rustin, his complicated legacy pushes us to analyze our own complicated times. Vilified in the 1950s for his open homosexuality and again in the 1960s for "selling out" the radical black liberation movement, Rustin's own history has been recently rescued by the books and movie correctly extolling his incredible gifts as a grassroots organizer, a charismatic orator and a visionary thinker. As preparations proceed for the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (of which Rustin was the chief architect), and the dreams and nightmares of a new generation are being forged against a backdrop of pepper spray and tear gas, it is time to take a deeper look at the relationship between the movements for peace and for justice -- movements which are no more "integrated" now than they were 50 years ago.

It is important first to note that, just as the foundations for much of the 1950s tumult around civil rights were laid by the Tuskegee Airmen and other members of the U.S. Armed Forces of African descent, Rustin was a part of another grouping of World War II veterans. When the black vets who helped liberate Europe from fascism and open the doors of the concentration camps came home to find that democracy and equality was not forthcoming despite their heroic efforts, Rustin and his World War II conscientious objector colleagues had spent their war years behind bars. Many of them, including Rustin, Dave Dellinger, Ralph DiGia, George Houser and Bill Sutherland, were active in efforts to desegregate the federal prisons they were held in, a daring effort 10 years before the widespread lunch counter sit-in and bus boycott campaigns.

It must be understood as no coincidence that this generation, whose skills were honed and tested at a time when mass sentiment was neither anti-war nor particularly progressive, produced activists whose life-long commitments to fundamental social change led them to become long-term advocates for radical alternatives. Many of the most respected and serious leaders of the civil rights, Pan-Africanist, solidarity, anti-Vietnam War, anarchist, socialist and disarmament movements of the following five decades came out of the small cadre of World War II conscientious objectors who put organization before ego and linking struggles before leftist turf wars. These same activists, coming out of the religious as well as the secular pacifist movements, were amongst the first to label their brand of nonviolent action as explicitly revolutionary -- and worked to take over and increase the militancy within the existing groups of their time.

Setting the Record "Straight"

The classic Journey of Reconciliation photo of nine smiling men, black and white, suitcases in hand, has been used repeatedly to educate the generations since that corner-turning 1947 moment about the "first freedom ride." When, in 1942, the U.S. Supreme Court (twelve years before Brown vs. Board of Education) ruled that state segregation laws did not apply to interstate bus travel, the stirrings for a campaign began. The precocious James Farmer, who by age 21 had earned two college degrees and had developed a friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, appealed to the religious pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) to help him set up a group focusing on racial justice. Though the FOR did not agree to directly sponsor the new organization, their Executive Secretary -- A.J. Muste, himself a minister and a former labor leader -- helped provide the basic support to birth the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Farmer had been FOR secretary for race relations; when he left FOR staff to create CORE, fellow FOR staff members Bayard Rustin and George Houser played a major support role.

The 1947 journey, then, an integrated trip through the upper South directly challenging the new rulings on bus travel, was formally sponsored by CORE, largely organized by FOR staffers Rustin and Houser and made up of a total of 16 men. Of the nine in the well-known photo, Rustin and four others--Igal Roodenko, Jim Peck, Wally Nelson and Ernest Bromley--ended up playing key roles in the leadership of the secular pacifist War Resisters League (WRL) in the decades to follow; Houser and Rustin co-authored the FOR-CORE report on the journey, We Challenged Jim Crow! For defying southern custom, the bus riders were arrested several times, with Rustin eventually authoring "22 Days on a Chain Gang," a much-read pamphlet on his experiences.

Having served as an organizer of various Free India activities in support of Gandhi and the independence movement, Rustin traveled to India in 1948 for a long-planned conference that ended up taking place shortly after Gandhi's assassination. Rustin and Sutherland also made regular contact with the burgeoning anti-colonial movements in Africa, with special emphasis on contacts in Nigeria and South Africa. In 1951, the two of them joined Houser in setting up the Committee to Support South African Resistance, which evolved into the American Committee on Africa, for four decades the key U.S. African solidarity network. Working with a small group of existing contacts within the War Resisters International, Sutherland was able to travel to the Gold Coast in 1953 -- the British colony that would soon achieve independence through nonviolent civil resistance, and change its name back to the historic kingdom long developed in that West African territory: Ghana. Sutherland remained in Africa for 50 years, an unofficial ambassador of revolutionary nonviolence working closely with the ideologically and tactically diverse liberation movements. But Rustin's life in 1953 was to take another turn: though never secretive about his sexuality, he was arrested in a car with two other men during a Quaker conference in Pasadena (in California, in part, to raise money for a planned trip to Nigeria). Charged with vagrancy and lewd conduct, he pled guilty to the single, lesser charge of "sex perversion," as consensual homosexual activity was referred to in California at that time.

Back in New York, the officers of FOR were worried about the reputation of the organization given the new attention which Rustin's arrest brought up regarding matters of sexual orientation. FOR policy regarding Rustin had been that he remain both quiet and abstinent -- refraining from discussing or engaging in any sexual activity whatsoever, publicly or privately. With the California "incident" suggesting an inability to comply with this policy, the FOR asked Rustin to resign from staff; Muste threatened Rustin with firing if he did not comply. His resignation was also marked by a letter of resignation from the Executive Committee of the War Resisters League, but the WRL refused to accept Rustin's stepping down. In a short period of time, in fact -- by August of 1953 -- the officers of the WRL (in many ways a sister organization to FOR) decided to offer Rustin a position on their staff, recognizing in him the talents that would later dazzle the young Martin Luther King, Jr. and a new generation of southern blacks looking to intensify the battle against segregation. WRL's process of hiring Rustin, however, was not without its own controversies.

Though WRL Chair Roy Finch and WRL Executive Secretary Sid Aberman came to a joint agreement that hiring Rustin would provide "a unique opportunity" for the organization, and a proposal was put into place to hire both Rustin and Quaker leader Arlo Tatum as co-executive secretaries, there was much internal debate within the WRL Executive Committee and Advisory Board. Muste and Houser held roles as WRL executive members as well as their staff positions in FOR, but their individual feelings were split about the proposal. Arlo's own brother Lyle Tatum, executive director of the Central Committee on Conscientious Objection at the time, wrote that Rustin had greater abilities to lead the work of the nonviolent movement "than any other person with even a remote possibility of availability." Despite this, Tatum called to question whether WRL would be open to public attack if Rustin were to be hired, and whether future American Friends Service Committee and FOR cooperation with WRL could continue with Rustin on staff; he objected to the proposal "solely because of Bayard's public record of homosexual practices." Frances Witherspoon echoed the common refrain that "the psychological and physical trouble from which he suffers is not a recent one, but of fairly long standing, and I do not feel that the recent regrettable episode is far enough in the past." And WRL Advisory Committee member George W. Hartmann, the university psychologist for Columbia University and professor of psychology at Roosevelt College voiced the prevailing "professional" opinion of the time. "Bayard's 'malady,'" Hartmann noted, "is a peculiarly obdurate one (according to most clinical experience) and I should be violating my psychological insights did I not enter a plea at this time for persistent vigilance, so that organizationally we do not suffer from any possible 'relapse.' I confess I know no easy way to make such 'preventive hygiene' effective, but it seems only fair to Bayard that we be as intelligent and humane in helping him--and the Peace Movement--as we possibly can."

The proposal to hire Rustin prevailed, with some interesting insights expressed amongst the majority. Within the field of psychology was an advisor offering a more forward-looking view in the person of Herbert Kellman, at the time a post-doctoral research fellow of the U.S. Public Health Service at the Psychological Clinic at John Hopkins University. Kellman, now a long-standing professor at Harvard and innovator in the field of mediation, wrote to WRL Chair Finch that "it would be a shame for the pacifist movement to waste the talents, skills, and experience that Bayard has ... there is little question that Bayard will be able to handle the job successfully despite his so-called 'emotional problems.'" Fellow World War II conscientious objector Dave Dellinger, not yet himself an iconic anti-war figure, offered four pages of prophetic support for Rustin, stating that though Rustin's sexual orientation might be going against the "dominant sexual mores," there could be "no sense in trying to force on Bayard a Puritanical abstinence from the form of sex which apparently is natural to him." Suggesting that the WRL and the movement as a whole should be wiser than to continue the position of "rigid abstinence," Dellinger also noted that "the power of nonviolence works ... through dedicated people" and those so dedicated should be educated about the importance of what Rustin had to offer. Comparing the nonviolent positions of groups such as the WRL and FOR with mass-based electoral campaigns, Dellinger wrote: "I would rather take a chance of losing a thousand votes and winning a hundred pacifists, by having Bayard work for us." Concerned that an irrelevant nonviolent movement could suffer "the unity of the grave," Dellinger concluded that what Rustin's "exceptional talents and dedication" brought to the WRL, and what FOR was now lacking, was "a grass-roots, dynamic pacifism."

So it was, in the fall of 1953, that Bayard Rustin became executive secretary of the War Resisters League.

For Jobs and Freedom

Bayard Rustin's first years on the staff of the War Resisters League marked a period which historian Scott Bennett has called "the rebirth of the peace movement." Undoubtedly a good portion of that energy came from the work of Rustin. In addition to directing the League's general disarmament and anti-war work, youth and student outreach, and general organizational maintenance, Rustin helped the WRL found Liberation magazine in 1956 and pushed for further engagement with the growing civil rights campaigns. Some saw Rustin's public profile as too controversial to handle, as evidenced by the absence of his name on the influential 1955 American Friends Service Committee booklet he helped to author -- Speak Truth to Power: A Quaker Search for an Alternative to Violence -- a primer on nonviolent solutions to the Cold War. February 1956 saw the publishing of the first of a series of WRL reports written by Rustin about the movements in the south, called "Report from Montgomery, Alabama." In case there was to be any doubt about Rustin's effectiveness, a preface to the pamphlet quoted Unitarian minister Homer Jack that Rustin's counseling and trainings were especially crucial in the weeks following the mass arrests, and that "his contribution to interpreting the Gandhian approach to leadership cannot be overestimated." A year later, Rustin authored and WRL published a new report, "Non-Violence in the South," which outlined the deepening work being done against Jim Crow.

A 1959 WRL fundraising letter penned by Rustin spoke of the "vast changes" which were taking place in the years of the bus boycott and beyond. Speaking about a nationally-publicized North Carolina incident which raised the question of armed self-defense, Rustin wrote: "When the NAACP dismissed Robert Williams as its President in North Carolina because he advocated that 'Negroes should return violence with violence,' the Negro community was gravely split and much of the education on nonviolence was undone. Immediately our staff ... helped arrange for articles on the subject by both Mr. Williams and Rev. Martin Luther King in the pages of Liberation. We are also bringing Mr. Williams to New York to debate with pacifists on October 1. This will be the first public discussion of the question at which the War Resisters League point of view will be presented in the middle of one of the hottest issues of today." The "WRL position" was framed and articulated by Rustin -- whose commitment to nonviolent direct action was matched by his willingness to dialogue and debate with those who disagreed.

By the end of 1959, however, the anti-segregation and southern empowerment work was too pressing to have Rustin remain based at WRL headquarters in New York. With the intervention and assistance of labor leader A. Philip Randolph, whose Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was amongst the first unions to successfully organize black workers and challenge the racial divides within the American Federation of Labor, Rustin was asked to work directly as a full-time advisor to Rev. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). SCLC actually emerged as an organization to support King's work with other clergy and lay people throughout the South, growing out of an idea developed by Rustin and implemented by Rustin and legendary organizer Ella Baker (who went on to help found and mentor the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, the "youth division" of the civil rights movement). A 1960 letter from Randolph (who had become close to Muste during Muste's years as a socialist union organizer) to WRL Chair Eddie Gottlieb thanked the WRL for enabling Rustin to fulfill the "supremely important assignment ... in the interest of civil rights." A letter to Gottlieb from Rev. King reiterated his gratitude to WRL, and that "we are thoroughly committed to the method of nonviolence in our struggle and we are convinced that Bayard's expertness and commitment in this area will be of inestimable value in our future efforts." An "inner strategy committee" of King, Randolph, Muste, Gottlieb, Stanley Levison (a NY-based businessman who was a friend and advisor to King) and Rustin was set up to review the work as it related to "its contribution to the cause of nonviolence."

By 1963, Rustin was immersed in the work for a March on Washington, a dream of A. Philip Randolph's since the 1940s. When then-President Franklin Roosevelt established the federal Committee on Fair Employment Practice in 1941, effectively banning discriminatory hiring in the U.S. defense industry, Randolph called off the mass demonstration intended to pressure the White House. But the late 1950s, however, marked a time when federal action on behalf of disenfranchised blacks was far from a given, and the growing grassroots initiatives throughout the South could well be mobilized into a massive show of political force. Rustin was acknowledged as the best coordinator for such a unifying task, and the March for Jobs and Freedom, or Great March, was set for August on the 100th anniversary of Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. Writing as the on-leave WRL executive secretary, Rustin noted that the nation was "in deep crisis in civil rights, North and South." With the growing popularity of Malcolm X and the black Muslims, the validity and relevance of nonviolence was being called into question. "Fortunately," Rustin suggested, "the heroic nonviolent resistance in Birmingham has temporarily restored the faith of many black people." Rustin's reporting on The Meaning of Birmingham, published in Liberation and reprinted by WRL in pamphlet form as a mobilizing tool for the March, explained that "the mood is one of anger and confidence of total victory ... One can only hope that the white community will realize that the black community means what it says: freedom now."

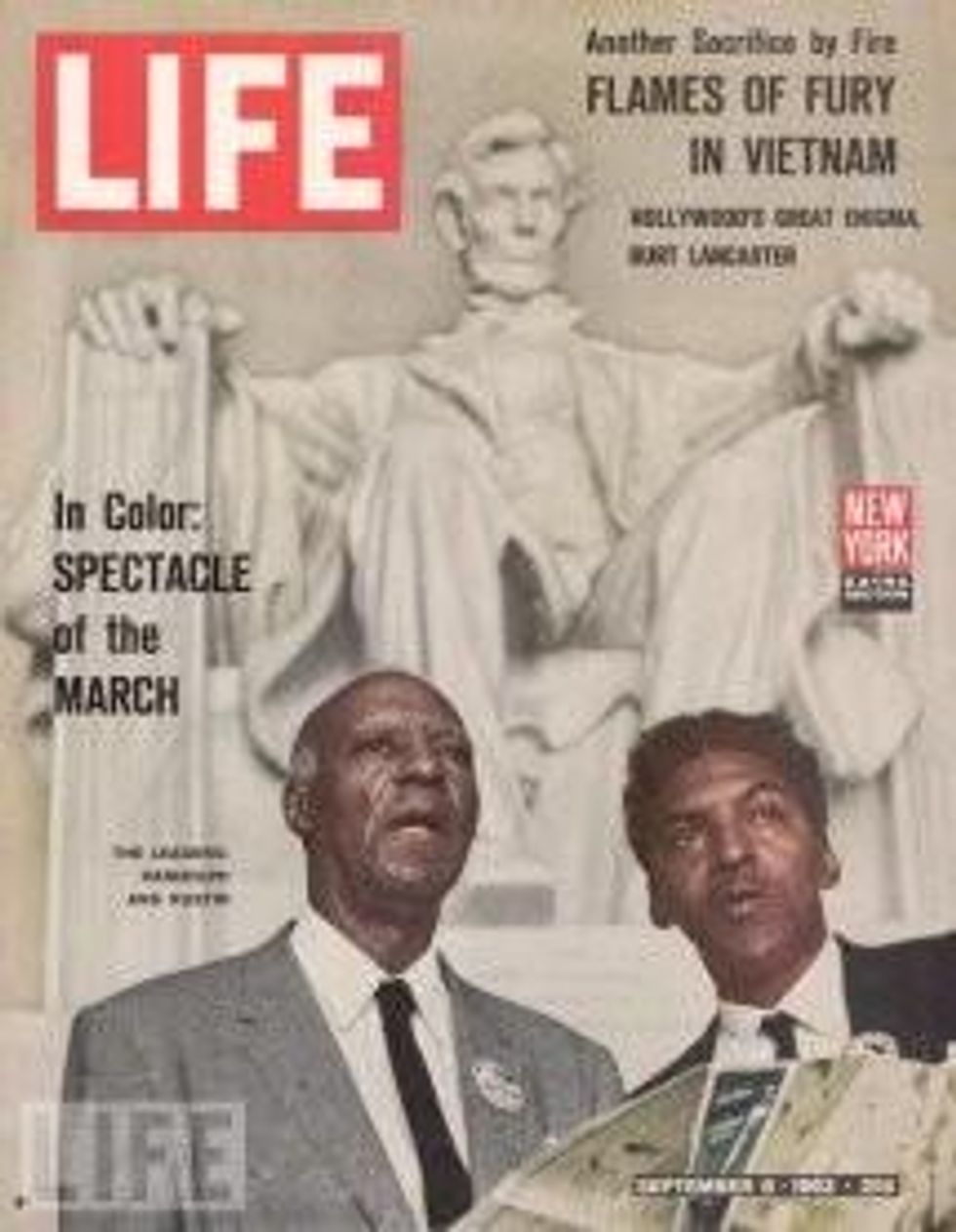

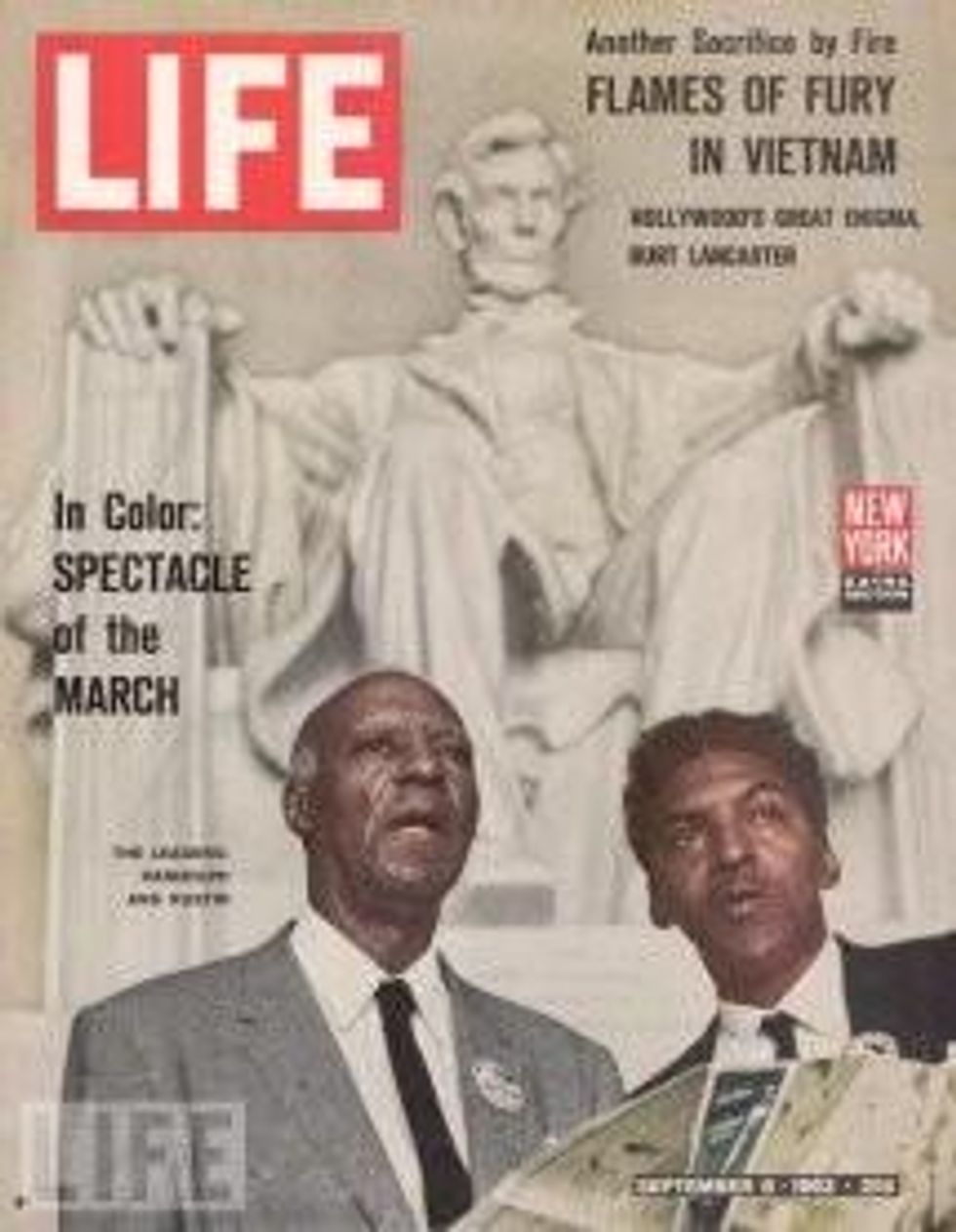

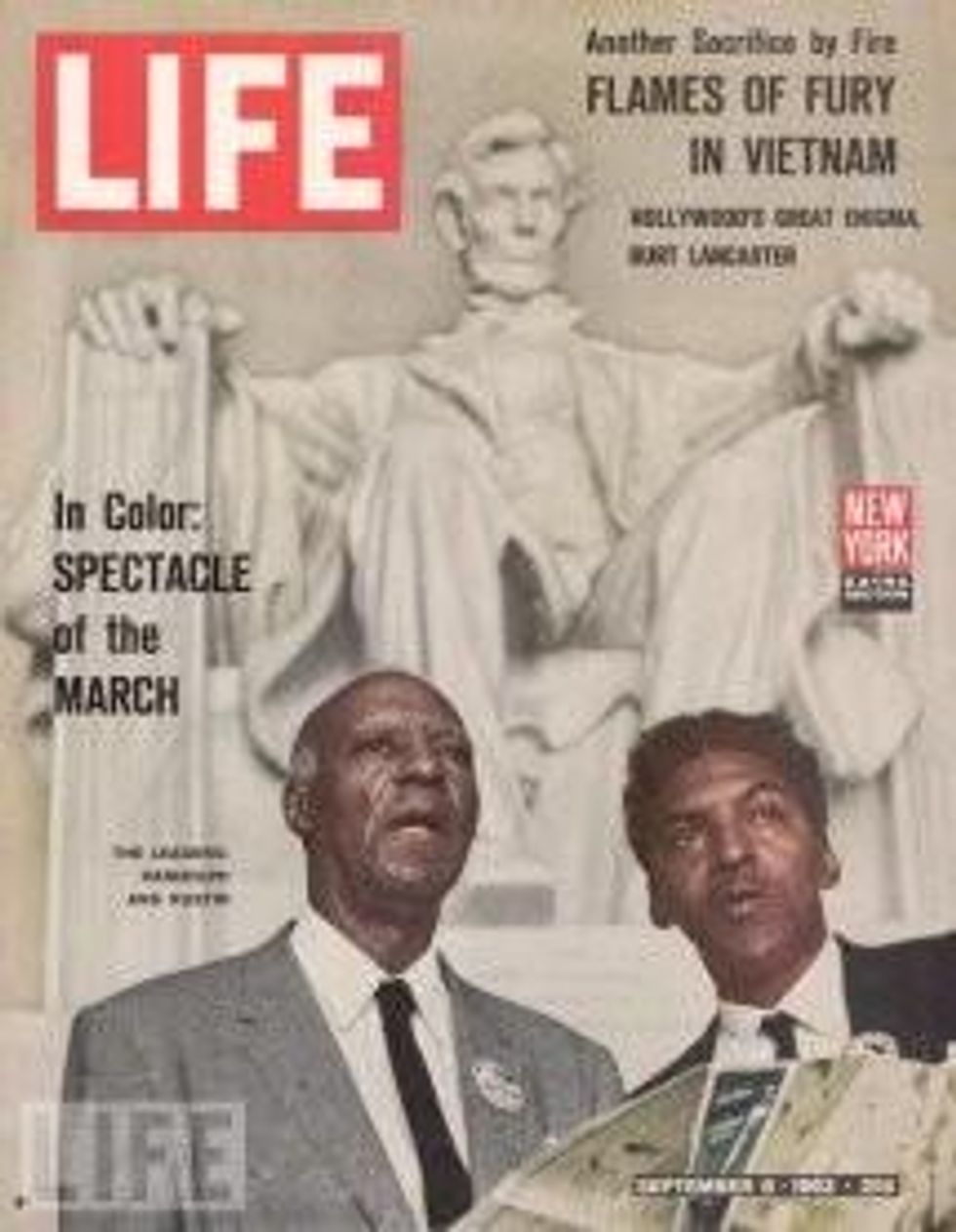

With 250,000 people assembled on the Great Lawn from every corner of the country, and its apparent direct effects on the halls of power, interest in mass civil resistance increased. As word spread throughout the U.S. of the mighty "I Have a Dream" oratory of Dr. King, and The New York Times focused attention on the radical testimonial in the speech of SNCC representative John Lewis the morning after the March, the full color photo on the cover of LIFE magazine was that of Randolph and Rustin, standing proudly in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Mixing Politics and Resistance, Peace and Freedom

The months and years that followed must have been a blur for most people working full-time on anti-war and anti-racist issues. On the one hand, the March and the movement seemed singularly responsible for forcing the politicians of the time to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Less than six months after the March, Rustin was responsible for an even more massive display of direct action, as hundreds of thousands of parents, students and ant-segregation activists took part in a one-day citywide boycott of the New York City public school system. On February 3, 1964, an estimated 450,000, mainly-black and Puerto Rican students stayed away from their assigned schools (many attending ad-hoc Freedom Schools at local churches and community centers for the day), calling on the city to set a clear timetable for an integrated system that would end the de facto separate and unequal school districts. Peace groups largely supported the effort (Eddie Gottlieb himself was not only WRL's chair but a principal in the Department of Education), and though short-term goals were not immediately met, the long-term ramifications of such a broad and activist coalition were daunting to the powers that be.

At the same time, however, with an apparent military incident in the Southeast Asian Gulf of Tonkin, the U.S. "police action" in Vietnam was growing more war-like with every passing day. As some leaders suggested that the time had come for the protest movement to escalate its tactics of resistance, Rustin authored an influential paper, "From Protest to Politics," which outlined a strategic need for the black-led freedom movement to shift away from militancy and resistance in the cause of equal rights towards forging greater social, electoral and economic alliances with the predominantly white trade union movement, liberal churches and politicians for the development of a movement that would probe and correct the contradictions of President Johnson's proposed "Great Society" for all working Americans.

In this context, Rustin hoped that his colleagues in the WRL and other peace groups would be able to join in the grand coalition which would work at the very center of the U.S. power structure. "One of the most urgent problems in the peace movement today," Rustin wrote in April 1964, "is how to 'relate' the issue of peace to the other great social issues of our day -- Civil Rights, unemployment, automation." While acknowledging that the WRL, because of its commitment to nonviolence, "has at times been termed dogmatic or inflexible in its consistently radical position," Rustin commented that, based on its early and creative support of African resistance and its flexibility in aligning with the civil rights movement, he knew "of no other organization -- in or out of the peace movement -- which has more consistently and effectively done this job of relating." The problem was, there was no agreement as to where the emphasis on such a series of relationships should be put. For Rustin, the choice was clear; when an institute was set up following the passage of the Voting Rights Act -- named after and presided over by his mentor A. Philip Randolph -- Rustin accepted the challenge of becoming its executive director working to strengthen the civil rights-labor connection. For the WRL and most other peace groups, the choice was to focus on the war in Vietnam, a decision which brought them into further opposition with the U.S. government.

In the early years of anti-war resistance, these differences in emphasis did not cause significant problems. Still writing as WRL executive secretary in July 1964, Rustin asserted that Vietnam was the U.S.' "dirty war," like the bloody war for Algerian independence was for France a decade prior. One of the first major anti-war rallies was held in New York's Madison Square Garden, and featured both Rustin and Coretta Scott King. In a speech (to be published for the first time in the forthcoming PM Press/WRL book We Have Not Been Moved: Resisting Racism and Militarism in 21st Century America), Rustin exclaimed:

Though Congress refuses to admit it, we are at war. It is a useless, destructive, disgusting war ...We must be on the side of revolutionary democracy. And, in addition to all the other arguments for a negotiated peace in Vietnam, there is this one: that it is immoral, impractical, un-political, and unrealistic for this nation to identify itself with a regime which does not have the confidence of its people ... I say to the President: American cannot be the policeman of this globe!

Though critics of Rustin claim that his opposition to the war was unclear at best, and that the alliances he made with the AFL-CIO neutralized his nonviolent politics, at the crucial early stages of anti-war movement-building in 1965, the links he made were more than clear: "The actor Ossie Davis," Rustin recalled, "recently pointed out that we must say to the President: 'If you want us to be nonviolent in Selma, why can't you be nonviolent in Saigon?'" There was no restrained militancy in Rustin's reminder that "the civil rights movement begged and begged for change, but finally learned this lesson -- going into the streets. The time is so late, the danger so great, that I call upon all the forces which believe in peace to take a lesson from the labor movement, the women's movement, and the civil rights movement and stop staying indoors. Go into these streets until we get peace!"

Nonetheless, the strategic and tactical differences in direction proved to be too great. On November 16, 1965, Bayard Rustin formally resigned from his executive position within the War Resisters League, in part because of his "distress and concern" over WRL policies regarding Vietnam. Rustin's resignation was set in the context of the "great affection" which he felt for the organization, and he agreed less than two months later to serve on the WRL Advisory Council; seven years later, when many contentious splits in the left had occurred during the long course of the extended war, both Rustin and Randolph nevertheless agreed to serve on the League's 50th Anniversary Commemoration Committee. But the close and consistent contact which had marked over two decades of communication between Rustin and his radical pacifist comrades was, for a time, now broken.

Rapprochement and Renewed Resistance

The late 1960s were at best a trying time for the coalition which had brought together moderate civil rights groups from the South, northern liberals (including the mainstream trade union movement), and radicals who saw the importance of working against the most overt and dramatic instances of racism in U.S. society. With the assassination of Muslim minister Malcolm X, and the ever-escalating war in Southeast Asia, the idea that fundamental change and equality could come about through nonviolent means seemed incredulous to many. Even the greatest symbol of nonviolence (and perhaps its most strategic practitioner) -- Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., now a Nobel Peace prize recipient -- was, by 1968, sounding a bit more open than usual to supporting the national liberation movement of the Vietnamese.

The inroads that Rustin had made with the massive 1964 schools boycott put him closer to the activities of Al Shanker and the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), which had just won the right to collective bargaining a few years earlier. In 1967, when rumblings about community control of the schools in black neighborhoods began spreading throughout the New York City, Rustin made the fateful choice to side with his labor allies -- a move that in many ways defined his split with parts of the black movement. The local autonomy of black-led schools was contrary to the UFT notion of inter-racial worker's rights and the need for united fronts against the always-recalcitrant Board of Education. In Rustin's words, Black Power in general and community control in particular were impediments to "authentic revolution," and a "giant hoax" which "would bring about the opposite of self-determination, because it can only lead to continued subjugation." Neither fighting against the war, nor working to empower the black community was as important as working with the UFT to ensure the gains of the "integrated" working class. At Rustin's suggestion, King sent words of support and a donation to Shanker's bail fund when Shanker was jailed for leading a strike for smaller class size.

Many of the young activists of the SNCC were already harshly critical of Rustin, as the 1964 conflicts at the Democratic National Convention with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) caused many to lose faith in "the system" altogether -- and Rustin's tepid support of the MFDP and collusion with President Johnson caused a similar loss of faith in him. As historian Claiborne Carson described in a recent presentation, his own more balanced analysis of Rustin took years to develop, after his initial negative feelings as a young person in SNCC. Stokley Carmichael's moving of SNCC away from nonviolence and towards Black Power intensified these divisions, which were to be solidified in short order. The demoralization which swept the peace and civil rights movements following the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King further set the tone for the disunity and confusion which were to follow. In a note from Rustin to Bill Sutherland in Tanzania shortly after the murder, he confessed to being "too discombobulated to write a coherent letter ... Martin's death leaves a fantastic vacuum that nobody -- not me and ten others combined -- could fill."

When a fall 1968 UFT strike took place against the abridgement of due process rights of several white teachers by the black-led Ocean Hill-Brownsville community-controlled school district, the historically positive and mutually supportive relationship between New York City's progressive Black and Jewish communities was torn asunder. A few short months earlier, Rustin accepted the UFT's prestigious John Dewey Award with a speech on "integration without decentralization." Rustin was alone amongst black leaders in standing with the union and supporting the strike.

Seventeen years later, this writer -- a newly hired social studies teacher whose father was a UFT Chapter Leader throughout the tumultuous 1960s strikes (but whose years as a young activist had led me to significant criticism of the racism in the UFT and elsewhere) -- understood the irony and significance of heading towards the main headquarters of the now-powerful teacher's union, to the offices of the A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI) and its director, Bayard Rustin. Throughout the 1970s, Rustin's connection to the mainstream labor bureaucracy was solidified through a number of positions and actions. As public spokesperson of the Social Democrats, he helped lead the push for increasing AFL-CIO work on overall economic justice issues -- while simultaneously taking strong anti-communist positions and criticizing some liberal positions as well. As a vice chairman of the International Rescue Committee, Rustin traveled around the world on behalf of the rights of refugees, including five trips to Thailand between 1978 and 1987 to spotlight the plight of Vietnam's "boat people." As Executive Committee chairman of Freedom House, he was an election observer in Zimbabwe, El Salvador and Grenada; Rustin was central to organizing the black Americans to thSupport Israel Committee. Now, my own work in the anti-apartheid movement and interest in the Gandhian legacy in India was dovetailing with a renewed interest on Rustin's part in reaching back to his radical pacifist roots.

At the end of 1985, the War Resisters International held its triennial conference in the province of Gujarat, India -- home to Gandhi, his ashram, and so many of the institutions set up by the nonviolent movements of the last half century. A special guest, attending not as a speaker or presenter or honoree, was Bayard Rustin, interested in checking out the organization he had been so integral to. As a public non-registrant who had just become the youngest national chairperson of the WRL, I was in attendance as convener of the theme group on conscientious objection and resistance to conscription. I had also recently developed a special relationship with the newly-formed End Conscription Campaign (ECC) of South Africa, the coalition which was bringing together unprecedented numbers of whites into nonviolent confrontation with the racist regime. ECC's national director, Laurie Nathan, was with us as part of the theme group, as was ECC activist Peter Hawthorne, South African Council of Churches representative Rev. John Lamola, and a representative of the women's organization Black Sash. Laurie, Peter and I had traversed northern Europe, England, and India to spread the word of the connections between resisting racism and militarism, but were especially interested in meeting that man who had such a rich but controversial history in making those same links. The interest was unmistakably mutual, as Rustin took a keen notice of the work of ECC and the developments on the ground in South Africa.

In the months that followed, Rustin became a key fiscal and political supporter of the ECC, helping to funnel funds from the Quaker New York Friends Group with whom he had maintained a close connection. The meeting at the APRI offices in the UFT headquarters was one of a growing number of discussions and reunions I took part in, with Bayard's old colleagues Ralph DiGia and David McReynolds in attendance. At one such get-together, we learned of the forthcoming 75th birthday celebration, planned to fete Bayard at New York's famed Hilton Hotel. The invitation showcased the sometimes unlikely partners in commemorating the achievements of this complicated man. Germany's socialist Willy Brandt joined with the AFL-CIO's arch anti-communist president Lane Kirkland; Indian pacifists Narayan Desai and Devi Presad served as international sponsors alongside Israeli militarists Yitzhak Shamir and Shimon Peres, Norwegian actress Liv Ullman, and many others. For us, a rag-tag group of nonviolent campaigners made up a dinner table at the event, including DiGia, McReynolds and I, along with Igal Roodenko and Laurie Nathan -- who happened to be in town for a U.S. speaking tour. UFTers Albert Shanker and Sandy Feldman were happily part of the festivities, as we listened to tribute after tribute, including from former SNCC militant turned-U.S. Congressman John Lewis, former Urban League president Vernon Jordan, and recently awarded Nobel Peace Laureate Elie Wiesel; U.S. Presidents Ford and Carter each sent greetings. The diversity of attendees and supporters spoke volumes about the ways in which Rustin's rich life had impacted positively on a wide spectrum of peoples.

One aspect of Rustin's interest in rapprochement and the grassroots may have been due to the renewed attention he was receiving from the activist community since appearing on the July 1986 cover of Gay Community News. As the LGBT movement was growing by leaps and bounds, Rustin provided a special kind of solidarity by suggesting that the campaign for gay right was akin to the civil rights movement of its time. Rustin cautioned, however, the wise idea that solidarity must always be a two-way endeavor. "If we want some civil rights advocates to help us," he proclaimed in the Gay Community News interview, "that means we'll have to be looked upon by civil rights groups as a group that is going to help them."

And then he was gone. This high-spirited, flamboyant, funny, brilliant, challenging soul force -- this strong and courageous spirit who seemed always filled with energy and passion -- passed away less than six months after his birthday dinner. The strain of an emergency operation for a perforated appendix caused a heart attack that his body could not endure. But his legacy, like his entire life, was a beacon of the power of positive action. The typically diverse group of people who packed Community Church for Bayard Rustin's funeral were treated to the same words pledged by March participants in front of the Lincoln Memorial that fateful August day in 1963. An organizer till the very end, his life partner Walter Naegle made sure that each memorial program spotlighted the words which summarized Rustin's undying outlook:

I pledge that I will join and support all actions undertaken in good faith and in accord with time-honored democratic traditions of nonviolent protest or peaceful assembly and petition ... I will pledge my heart and my mind and my body, unequivocally and without regard to personal sacrifice to the achievement of social peace through social justice.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

One hundred years after the birth of human rights icon Bayard Rustin, his complicated legacy pushes us to analyze our own complicated times. Vilified in the 1950s for his open homosexuality and again in the 1960s for "selling out" the radical black liberation movement, Rustin's own history has been recently rescued by the books and movie correctly extolling his incredible gifts as a grassroots organizer, a charismatic orator and a visionary thinker. As preparations proceed for the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (of which Rustin was the chief architect), and the dreams and nightmares of a new generation are being forged against a backdrop of pepper spray and tear gas, it is time to take a deeper look at the relationship between the movements for peace and for justice -- movements which are no more "integrated" now than they were 50 years ago.

It is important first to note that, just as the foundations for much of the 1950s tumult around civil rights were laid by the Tuskegee Airmen and other members of the U.S. Armed Forces of African descent, Rustin was a part of another grouping of World War II veterans. When the black vets who helped liberate Europe from fascism and open the doors of the concentration camps came home to find that democracy and equality was not forthcoming despite their heroic efforts, Rustin and his World War II conscientious objector colleagues had spent their war years behind bars. Many of them, including Rustin, Dave Dellinger, Ralph DiGia, George Houser and Bill Sutherland, were active in efforts to desegregate the federal prisons they were held in, a daring effort 10 years before the widespread lunch counter sit-in and bus boycott campaigns.

It must be understood as no coincidence that this generation, whose skills were honed and tested at a time when mass sentiment was neither anti-war nor particularly progressive, produced activists whose life-long commitments to fundamental social change led them to become long-term advocates for radical alternatives. Many of the most respected and serious leaders of the civil rights, Pan-Africanist, solidarity, anti-Vietnam War, anarchist, socialist and disarmament movements of the following five decades came out of the small cadre of World War II conscientious objectors who put organization before ego and linking struggles before leftist turf wars. These same activists, coming out of the religious as well as the secular pacifist movements, were amongst the first to label their brand of nonviolent action as explicitly revolutionary -- and worked to take over and increase the militancy within the existing groups of their time.

Setting the Record "Straight"

The classic Journey of Reconciliation photo of nine smiling men, black and white, suitcases in hand, has been used repeatedly to educate the generations since that corner-turning 1947 moment about the "first freedom ride." When, in 1942, the U.S. Supreme Court (twelve years before Brown vs. Board of Education) ruled that state segregation laws did not apply to interstate bus travel, the stirrings for a campaign began. The precocious James Farmer, who by age 21 had earned two college degrees and had developed a friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, appealed to the religious pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) to help him set up a group focusing on racial justice. Though the FOR did not agree to directly sponsor the new organization, their Executive Secretary -- A.J. Muste, himself a minister and a former labor leader -- helped provide the basic support to birth the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Farmer had been FOR secretary for race relations; when he left FOR staff to create CORE, fellow FOR staff members Bayard Rustin and George Houser played a major support role.

The 1947 journey, then, an integrated trip through the upper South directly challenging the new rulings on bus travel, was formally sponsored by CORE, largely organized by FOR staffers Rustin and Houser and made up of a total of 16 men. Of the nine in the well-known photo, Rustin and four others--Igal Roodenko, Jim Peck, Wally Nelson and Ernest Bromley--ended up playing key roles in the leadership of the secular pacifist War Resisters League (WRL) in the decades to follow; Houser and Rustin co-authored the FOR-CORE report on the journey, We Challenged Jim Crow! For defying southern custom, the bus riders were arrested several times, with Rustin eventually authoring "22 Days on a Chain Gang," a much-read pamphlet on his experiences.

Having served as an organizer of various Free India activities in support of Gandhi and the independence movement, Rustin traveled to India in 1948 for a long-planned conference that ended up taking place shortly after Gandhi's assassination. Rustin and Sutherland also made regular contact with the burgeoning anti-colonial movements in Africa, with special emphasis on contacts in Nigeria and South Africa. In 1951, the two of them joined Houser in setting up the Committee to Support South African Resistance, which evolved into the American Committee on Africa, for four decades the key U.S. African solidarity network. Working with a small group of existing contacts within the War Resisters International, Sutherland was able to travel to the Gold Coast in 1953 -- the British colony that would soon achieve independence through nonviolent civil resistance, and change its name back to the historic kingdom long developed in that West African territory: Ghana. Sutherland remained in Africa for 50 years, an unofficial ambassador of revolutionary nonviolence working closely with the ideologically and tactically diverse liberation movements. But Rustin's life in 1953 was to take another turn: though never secretive about his sexuality, he was arrested in a car with two other men during a Quaker conference in Pasadena (in California, in part, to raise money for a planned trip to Nigeria). Charged with vagrancy and lewd conduct, he pled guilty to the single, lesser charge of "sex perversion," as consensual homosexual activity was referred to in California at that time.

Back in New York, the officers of FOR were worried about the reputation of the organization given the new attention which Rustin's arrest brought up regarding matters of sexual orientation. FOR policy regarding Rustin had been that he remain both quiet and abstinent -- refraining from discussing or engaging in any sexual activity whatsoever, publicly or privately. With the California "incident" suggesting an inability to comply with this policy, the FOR asked Rustin to resign from staff; Muste threatened Rustin with firing if he did not comply. His resignation was also marked by a letter of resignation from the Executive Committee of the War Resisters League, but the WRL refused to accept Rustin's stepping down. In a short period of time, in fact -- by August of 1953 -- the officers of the WRL (in many ways a sister organization to FOR) decided to offer Rustin a position on their staff, recognizing in him the talents that would later dazzle the young Martin Luther King, Jr. and a new generation of southern blacks looking to intensify the battle against segregation. WRL's process of hiring Rustin, however, was not without its own controversies.

Though WRL Chair Roy Finch and WRL Executive Secretary Sid Aberman came to a joint agreement that hiring Rustin would provide "a unique opportunity" for the organization, and a proposal was put into place to hire both Rustin and Quaker leader Arlo Tatum as co-executive secretaries, there was much internal debate within the WRL Executive Committee and Advisory Board. Muste and Houser held roles as WRL executive members as well as their staff positions in FOR, but their individual feelings were split about the proposal. Arlo's own brother Lyle Tatum, executive director of the Central Committee on Conscientious Objection at the time, wrote that Rustin had greater abilities to lead the work of the nonviolent movement "than any other person with even a remote possibility of availability." Despite this, Tatum called to question whether WRL would be open to public attack if Rustin were to be hired, and whether future American Friends Service Committee and FOR cooperation with WRL could continue with Rustin on staff; he objected to the proposal "solely because of Bayard's public record of homosexual practices." Frances Witherspoon echoed the common refrain that "the psychological and physical trouble from which he suffers is not a recent one, but of fairly long standing, and I do not feel that the recent regrettable episode is far enough in the past." And WRL Advisory Committee member George W. Hartmann, the university psychologist for Columbia University and professor of psychology at Roosevelt College voiced the prevailing "professional" opinion of the time. "Bayard's 'malady,'" Hartmann noted, "is a peculiarly obdurate one (according to most clinical experience) and I should be violating my psychological insights did I not enter a plea at this time for persistent vigilance, so that organizationally we do not suffer from any possible 'relapse.' I confess I know no easy way to make such 'preventive hygiene' effective, but it seems only fair to Bayard that we be as intelligent and humane in helping him--and the Peace Movement--as we possibly can."

The proposal to hire Rustin prevailed, with some interesting insights expressed amongst the majority. Within the field of psychology was an advisor offering a more forward-looking view in the person of Herbert Kellman, at the time a post-doctoral research fellow of the U.S. Public Health Service at the Psychological Clinic at John Hopkins University. Kellman, now a long-standing professor at Harvard and innovator in the field of mediation, wrote to WRL Chair Finch that "it would be a shame for the pacifist movement to waste the talents, skills, and experience that Bayard has ... there is little question that Bayard will be able to handle the job successfully despite his so-called 'emotional problems.'" Fellow World War II conscientious objector Dave Dellinger, not yet himself an iconic anti-war figure, offered four pages of prophetic support for Rustin, stating that though Rustin's sexual orientation might be going against the "dominant sexual mores," there could be "no sense in trying to force on Bayard a Puritanical abstinence from the form of sex which apparently is natural to him." Suggesting that the WRL and the movement as a whole should be wiser than to continue the position of "rigid abstinence," Dellinger also noted that "the power of nonviolence works ... through dedicated people" and those so dedicated should be educated about the importance of what Rustin had to offer. Comparing the nonviolent positions of groups such as the WRL and FOR with mass-based electoral campaigns, Dellinger wrote: "I would rather take a chance of losing a thousand votes and winning a hundred pacifists, by having Bayard work for us." Concerned that an irrelevant nonviolent movement could suffer "the unity of the grave," Dellinger concluded that what Rustin's "exceptional talents and dedication" brought to the WRL, and what FOR was now lacking, was "a grass-roots, dynamic pacifism."

So it was, in the fall of 1953, that Bayard Rustin became executive secretary of the War Resisters League.

For Jobs and Freedom

Bayard Rustin's first years on the staff of the War Resisters League marked a period which historian Scott Bennett has called "the rebirth of the peace movement." Undoubtedly a good portion of that energy came from the work of Rustin. In addition to directing the League's general disarmament and anti-war work, youth and student outreach, and general organizational maintenance, Rustin helped the WRL found Liberation magazine in 1956 and pushed for further engagement with the growing civil rights campaigns. Some saw Rustin's public profile as too controversial to handle, as evidenced by the absence of his name on the influential 1955 American Friends Service Committee booklet he helped to author -- Speak Truth to Power: A Quaker Search for an Alternative to Violence -- a primer on nonviolent solutions to the Cold War. February 1956 saw the publishing of the first of a series of WRL reports written by Rustin about the movements in the south, called "Report from Montgomery, Alabama." In case there was to be any doubt about Rustin's effectiveness, a preface to the pamphlet quoted Unitarian minister Homer Jack that Rustin's counseling and trainings were especially crucial in the weeks following the mass arrests, and that "his contribution to interpreting the Gandhian approach to leadership cannot be overestimated." A year later, Rustin authored and WRL published a new report, "Non-Violence in the South," which outlined the deepening work being done against Jim Crow.

A 1959 WRL fundraising letter penned by Rustin spoke of the "vast changes" which were taking place in the years of the bus boycott and beyond. Speaking about a nationally-publicized North Carolina incident which raised the question of armed self-defense, Rustin wrote: "When the NAACP dismissed Robert Williams as its President in North Carolina because he advocated that 'Negroes should return violence with violence,' the Negro community was gravely split and much of the education on nonviolence was undone. Immediately our staff ... helped arrange for articles on the subject by both Mr. Williams and Rev. Martin Luther King in the pages of Liberation. We are also bringing Mr. Williams to New York to debate with pacifists on October 1. This will be the first public discussion of the question at which the War Resisters League point of view will be presented in the middle of one of the hottest issues of today." The "WRL position" was framed and articulated by Rustin -- whose commitment to nonviolent direct action was matched by his willingness to dialogue and debate with those who disagreed.

By the end of 1959, however, the anti-segregation and southern empowerment work was too pressing to have Rustin remain based at WRL headquarters in New York. With the intervention and assistance of labor leader A. Philip Randolph, whose Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was amongst the first unions to successfully organize black workers and challenge the racial divides within the American Federation of Labor, Rustin was asked to work directly as a full-time advisor to Rev. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). SCLC actually emerged as an organization to support King's work with other clergy and lay people throughout the South, growing out of an idea developed by Rustin and implemented by Rustin and legendary organizer Ella Baker (who went on to help found and mentor the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, the "youth division" of the civil rights movement). A 1960 letter from Randolph (who had become close to Muste during Muste's years as a socialist union organizer) to WRL Chair Eddie Gottlieb thanked the WRL for enabling Rustin to fulfill the "supremely important assignment ... in the interest of civil rights." A letter to Gottlieb from Rev. King reiterated his gratitude to WRL, and that "we are thoroughly committed to the method of nonviolence in our struggle and we are convinced that Bayard's expertness and commitment in this area will be of inestimable value in our future efforts." An "inner strategy committee" of King, Randolph, Muste, Gottlieb, Stanley Levison (a NY-based businessman who was a friend and advisor to King) and Rustin was set up to review the work as it related to "its contribution to the cause of nonviolence."

By 1963, Rustin was immersed in the work for a March on Washington, a dream of A. Philip Randolph's since the 1940s. When then-President Franklin Roosevelt established the federal Committee on Fair Employment Practice in 1941, effectively banning discriminatory hiring in the U.S. defense industry, Randolph called off the mass demonstration intended to pressure the White House. But the late 1950s, however, marked a time when federal action on behalf of disenfranchised blacks was far from a given, and the growing grassroots initiatives throughout the South could well be mobilized into a massive show of political force. Rustin was acknowledged as the best coordinator for such a unifying task, and the March for Jobs and Freedom, or Great March, was set for August on the 100th anniversary of Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. Writing as the on-leave WRL executive secretary, Rustin noted that the nation was "in deep crisis in civil rights, North and South." With the growing popularity of Malcolm X and the black Muslims, the validity and relevance of nonviolence was being called into question. "Fortunately," Rustin suggested, "the heroic nonviolent resistance in Birmingham has temporarily restored the faith of many black people." Rustin's reporting on The Meaning of Birmingham, published in Liberation and reprinted by WRL in pamphlet form as a mobilizing tool for the March, explained that "the mood is one of anger and confidence of total victory ... One can only hope that the white community will realize that the black community means what it says: freedom now."

With 250,000 people assembled on the Great Lawn from every corner of the country, and its apparent direct effects on the halls of power, interest in mass civil resistance increased. As word spread throughout the U.S. of the mighty "I Have a Dream" oratory of Dr. King, and The New York Times focused attention on the radical testimonial in the speech of SNCC representative John Lewis the morning after the March, the full color photo on the cover of LIFE magazine was that of Randolph and Rustin, standing proudly in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Mixing Politics and Resistance, Peace and Freedom

The months and years that followed must have been a blur for most people working full-time on anti-war and anti-racist issues. On the one hand, the March and the movement seemed singularly responsible for forcing the politicians of the time to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Less than six months after the March, Rustin was responsible for an even more massive display of direct action, as hundreds of thousands of parents, students and ant-segregation activists took part in a one-day citywide boycott of the New York City public school system. On February 3, 1964, an estimated 450,000, mainly-black and Puerto Rican students stayed away from their assigned schools (many attending ad-hoc Freedom Schools at local churches and community centers for the day), calling on the city to set a clear timetable for an integrated system that would end the de facto separate and unequal school districts. Peace groups largely supported the effort (Eddie Gottlieb himself was not only WRL's chair but a principal in the Department of Education), and though short-term goals were not immediately met, the long-term ramifications of such a broad and activist coalition were daunting to the powers that be.

At the same time, however, with an apparent military incident in the Southeast Asian Gulf of Tonkin, the U.S. "police action" in Vietnam was growing more war-like with every passing day. As some leaders suggested that the time had come for the protest movement to escalate its tactics of resistance, Rustin authored an influential paper, "From Protest to Politics," which outlined a strategic need for the black-led freedom movement to shift away from militancy and resistance in the cause of equal rights towards forging greater social, electoral and economic alliances with the predominantly white trade union movement, liberal churches and politicians for the development of a movement that would probe and correct the contradictions of President Johnson's proposed "Great Society" for all working Americans.

In this context, Rustin hoped that his colleagues in the WRL and other peace groups would be able to join in the grand coalition which would work at the very center of the U.S. power structure. "One of the most urgent problems in the peace movement today," Rustin wrote in April 1964, "is how to 'relate' the issue of peace to the other great social issues of our day -- Civil Rights, unemployment, automation." While acknowledging that the WRL, because of its commitment to nonviolence, "has at times been termed dogmatic or inflexible in its consistently radical position," Rustin commented that, based on its early and creative support of African resistance and its flexibility in aligning with the civil rights movement, he knew "of no other organization -- in or out of the peace movement -- which has more consistently and effectively done this job of relating." The problem was, there was no agreement as to where the emphasis on such a series of relationships should be put. For Rustin, the choice was clear; when an institute was set up following the passage of the Voting Rights Act -- named after and presided over by his mentor A. Philip Randolph -- Rustin accepted the challenge of becoming its executive director working to strengthen the civil rights-labor connection. For the WRL and most other peace groups, the choice was to focus on the war in Vietnam, a decision which brought them into further opposition with the U.S. government.

In the early years of anti-war resistance, these differences in emphasis did not cause significant problems. Still writing as WRL executive secretary in July 1964, Rustin asserted that Vietnam was the U.S.' "dirty war," like the bloody war for Algerian independence was for France a decade prior. One of the first major anti-war rallies was held in New York's Madison Square Garden, and featured both Rustin and Coretta Scott King. In a speech (to be published for the first time in the forthcoming PM Press/WRL book We Have Not Been Moved: Resisting Racism and Militarism in 21st Century America), Rustin exclaimed:

Though Congress refuses to admit it, we are at war. It is a useless, destructive, disgusting war ...We must be on the side of revolutionary democracy. And, in addition to all the other arguments for a negotiated peace in Vietnam, there is this one: that it is immoral, impractical, un-political, and unrealistic for this nation to identify itself with a regime which does not have the confidence of its people ... I say to the President: American cannot be the policeman of this globe!

Though critics of Rustin claim that his opposition to the war was unclear at best, and that the alliances he made with the AFL-CIO neutralized his nonviolent politics, at the crucial early stages of anti-war movement-building in 1965, the links he made were more than clear: "The actor Ossie Davis," Rustin recalled, "recently pointed out that we must say to the President: 'If you want us to be nonviolent in Selma, why can't you be nonviolent in Saigon?'" There was no restrained militancy in Rustin's reminder that "the civil rights movement begged and begged for change, but finally learned this lesson -- going into the streets. The time is so late, the danger so great, that I call upon all the forces which believe in peace to take a lesson from the labor movement, the women's movement, and the civil rights movement and stop staying indoors. Go into these streets until we get peace!"

Nonetheless, the strategic and tactical differences in direction proved to be too great. On November 16, 1965, Bayard Rustin formally resigned from his executive position within the War Resisters League, in part because of his "distress and concern" over WRL policies regarding Vietnam. Rustin's resignation was set in the context of the "great affection" which he felt for the organization, and he agreed less than two months later to serve on the WRL Advisory Council; seven years later, when many contentious splits in the left had occurred during the long course of the extended war, both Rustin and Randolph nevertheless agreed to serve on the League's 50th Anniversary Commemoration Committee. But the close and consistent contact which had marked over two decades of communication between Rustin and his radical pacifist comrades was, for a time, now broken.

Rapprochement and Renewed Resistance

The late 1960s were at best a trying time for the coalition which had brought together moderate civil rights groups from the South, northern liberals (including the mainstream trade union movement), and radicals who saw the importance of working against the most overt and dramatic instances of racism in U.S. society. With the assassination of Muslim minister Malcolm X, and the ever-escalating war in Southeast Asia, the idea that fundamental change and equality could come about through nonviolent means seemed incredulous to many. Even the greatest symbol of nonviolence (and perhaps its most strategic practitioner) -- Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., now a Nobel Peace prize recipient -- was, by 1968, sounding a bit more open than usual to supporting the national liberation movement of the Vietnamese.

The inroads that Rustin had made with the massive 1964 schools boycott put him closer to the activities of Al Shanker and the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), which had just won the right to collective bargaining a few years earlier. In 1967, when rumblings about community control of the schools in black neighborhoods began spreading throughout the New York City, Rustin made the fateful choice to side with his labor allies -- a move that in many ways defined his split with parts of the black movement. The local autonomy of black-led schools was contrary to the UFT notion of inter-racial worker's rights and the need for united fronts against the always-recalcitrant Board of Education. In Rustin's words, Black Power in general and community control in particular were impediments to "authentic revolution," and a "giant hoax" which "would bring about the opposite of self-determination, because it can only lead to continued subjugation." Neither fighting against the war, nor working to empower the black community was as important as working with the UFT to ensure the gains of the "integrated" working class. At Rustin's suggestion, King sent words of support and a donation to Shanker's bail fund when Shanker was jailed for leading a strike for smaller class size.

Many of the young activists of the SNCC were already harshly critical of Rustin, as the 1964 conflicts at the Democratic National Convention with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) caused many to lose faith in "the system" altogether -- and Rustin's tepid support of the MFDP and collusion with President Johnson caused a similar loss of faith in him. As historian Claiborne Carson described in a recent presentation, his own more balanced analysis of Rustin took years to develop, after his initial negative feelings as a young person in SNCC. Stokley Carmichael's moving of SNCC away from nonviolence and towards Black Power intensified these divisions, which were to be solidified in short order. The demoralization which swept the peace and civil rights movements following the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King further set the tone for the disunity and confusion which were to follow. In a note from Rustin to Bill Sutherland in Tanzania shortly after the murder, he confessed to being "too discombobulated to write a coherent letter ... Martin's death leaves a fantastic vacuum that nobody -- not me and ten others combined -- could fill."

When a fall 1968 UFT strike took place against the abridgement of due process rights of several white teachers by the black-led Ocean Hill-Brownsville community-controlled school district, the historically positive and mutually supportive relationship between New York City's progressive Black and Jewish communities was torn asunder. A few short months earlier, Rustin accepted the UFT's prestigious John Dewey Award with a speech on "integration without decentralization." Rustin was alone amongst black leaders in standing with the union and supporting the strike.

Seventeen years later, this writer -- a newly hired social studies teacher whose father was a UFT Chapter Leader throughout the tumultuous 1960s strikes (but whose years as a young activist had led me to significant criticism of the racism in the UFT and elsewhere) -- understood the irony and significance of heading towards the main headquarters of the now-powerful teacher's union, to the offices of the A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI) and its director, Bayard Rustin. Throughout the 1970s, Rustin's connection to the mainstream labor bureaucracy was solidified through a number of positions and actions. As public spokesperson of the Social Democrats, he helped lead the push for increasing AFL-CIO work on overall economic justice issues -- while simultaneously taking strong anti-communist positions and criticizing some liberal positions as well. As a vice chairman of the International Rescue Committee, Rustin traveled around the world on behalf of the rights of refugees, including five trips to Thailand between 1978 and 1987 to spotlight the plight of Vietnam's "boat people." As Executive Committee chairman of Freedom House, he was an election observer in Zimbabwe, El Salvador and Grenada; Rustin was central to organizing the black Americans to thSupport Israel Committee. Now, my own work in the anti-apartheid movement and interest in the Gandhian legacy in India was dovetailing with a renewed interest on Rustin's part in reaching back to his radical pacifist roots.

At the end of 1985, the War Resisters International held its triennial conference in the province of Gujarat, India -- home to Gandhi, his ashram, and so many of the institutions set up by the nonviolent movements of the last half century. A special guest, attending not as a speaker or presenter or honoree, was Bayard Rustin, interested in checking out the organization he had been so integral to. As a public non-registrant who had just become the youngest national chairperson of the WRL, I was in attendance as convener of the theme group on conscientious objection and resistance to conscription. I had also recently developed a special relationship with the newly-formed End Conscription Campaign (ECC) of South Africa, the coalition which was bringing together unprecedented numbers of whites into nonviolent confrontation with the racist regime. ECC's national director, Laurie Nathan, was with us as part of the theme group, as was ECC activist Peter Hawthorne, South African Council of Churches representative Rev. John Lamola, and a representative of the women's organization Black Sash. Laurie, Peter and I had traversed northern Europe, England, and India to spread the word of the connections between resisting racism and militarism, but were especially interested in meeting that man who had such a rich but controversial history in making those same links. The interest was unmistakably mutual, as Rustin took a keen notice of the work of ECC and the developments on the ground in South Africa.

In the months that followed, Rustin became a key fiscal and political supporter of the ECC, helping to funnel funds from the Quaker New York Friends Group with whom he had maintained a close connection. The meeting at the APRI offices in the UFT headquarters was one of a growing number of discussions and reunions I took part in, with Bayard's old colleagues Ralph DiGia and David McReynolds in attendance. At one such get-together, we learned of the forthcoming 75th birthday celebration, planned to fete Bayard at New York's famed Hilton Hotel. The invitation showcased the sometimes unlikely partners in commemorating the achievements of this complicated man. Germany's socialist Willy Brandt joined with the AFL-CIO's arch anti-communist president Lane Kirkland; Indian pacifists Narayan Desai and Devi Presad served as international sponsors alongside Israeli militarists Yitzhak Shamir and Shimon Peres, Norwegian actress Liv Ullman, and many others. For us, a rag-tag group of nonviolent campaigners made up a dinner table at the event, including DiGia, McReynolds and I, along with Igal Roodenko and Laurie Nathan -- who happened to be in town for a U.S. speaking tour. UFTers Albert Shanker and Sandy Feldman were happily part of the festivities, as we listened to tribute after tribute, including from former SNCC militant turned-U.S. Congressman John Lewis, former Urban League president Vernon Jordan, and recently awarded Nobel Peace Laureate Elie Wiesel; U.S. Presidents Ford and Carter each sent greetings. The diversity of attendees and supporters spoke volumes about the ways in which Rustin's rich life had impacted positively on a wide spectrum of peoples.

One aspect of Rustin's interest in rapprochement and the grassroots may have been due to the renewed attention he was receiving from the activist community since appearing on the July 1986 cover of Gay Community News. As the LGBT movement was growing by leaps and bounds, Rustin provided a special kind of solidarity by suggesting that the campaign for gay right was akin to the civil rights movement of its time. Rustin cautioned, however, the wise idea that solidarity must always be a two-way endeavor. "If we want some civil rights advocates to help us," he proclaimed in the Gay Community News interview, "that means we'll have to be looked upon by civil rights groups as a group that is going to help them."

And then he was gone. This high-spirited, flamboyant, funny, brilliant, challenging soul force -- this strong and courageous spirit who seemed always filled with energy and passion -- passed away less than six months after his birthday dinner. The strain of an emergency operation for a perforated appendix caused a heart attack that his body could not endure. But his legacy, like his entire life, was a beacon of the power of positive action. The typically diverse group of people who packed Community Church for Bayard Rustin's funeral were treated to the same words pledged by March participants in front of the Lincoln Memorial that fateful August day in 1963. An organizer till the very end, his life partner Walter Naegle made sure that each memorial program spotlighted the words which summarized Rustin's undying outlook:

I pledge that I will join and support all actions undertaken in good faith and in accord with time-honored democratic traditions of nonviolent protest or peaceful assembly and petition ... I will pledge my heart and my mind and my body, unequivocally and without regard to personal sacrifice to the achievement of social peace through social justice.

One hundred years after the birth of human rights icon Bayard Rustin, his complicated legacy pushes us to analyze our own complicated times. Vilified in the 1950s for his open homosexuality and again in the 1960s for "selling out" the radical black liberation movement, Rustin's own history has been recently rescued by the books and movie correctly extolling his incredible gifts as a grassroots organizer, a charismatic orator and a visionary thinker. As preparations proceed for the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (of which Rustin was the chief architect), and the dreams and nightmares of a new generation are being forged against a backdrop of pepper spray and tear gas, it is time to take a deeper look at the relationship between the movements for peace and for justice -- movements which are no more "integrated" now than they were 50 years ago.

It is important first to note that, just as the foundations for much of the 1950s tumult around civil rights were laid by the Tuskegee Airmen and other members of the U.S. Armed Forces of African descent, Rustin was a part of another grouping of World War II veterans. When the black vets who helped liberate Europe from fascism and open the doors of the concentration camps came home to find that democracy and equality was not forthcoming despite their heroic efforts, Rustin and his World War II conscientious objector colleagues had spent their war years behind bars. Many of them, including Rustin, Dave Dellinger, Ralph DiGia, George Houser and Bill Sutherland, were active in efforts to desegregate the federal prisons they were held in, a daring effort 10 years before the widespread lunch counter sit-in and bus boycott campaigns.

It must be understood as no coincidence that this generation, whose skills were honed and tested at a time when mass sentiment was neither anti-war nor particularly progressive, produced activists whose life-long commitments to fundamental social change led them to become long-term advocates for radical alternatives. Many of the most respected and serious leaders of the civil rights, Pan-Africanist, solidarity, anti-Vietnam War, anarchist, socialist and disarmament movements of the following five decades came out of the small cadre of World War II conscientious objectors who put organization before ego and linking struggles before leftist turf wars. These same activists, coming out of the religious as well as the secular pacifist movements, were amongst the first to label their brand of nonviolent action as explicitly revolutionary -- and worked to take over and increase the militancy within the existing groups of their time.

Setting the Record "Straight"

The classic Journey of Reconciliation photo of nine smiling men, black and white, suitcases in hand, has been used repeatedly to educate the generations since that corner-turning 1947 moment about the "first freedom ride." When, in 1942, the U.S. Supreme Court (twelve years before Brown vs. Board of Education) ruled that state segregation laws did not apply to interstate bus travel, the stirrings for a campaign began. The precocious James Farmer, who by age 21 had earned two college degrees and had developed a friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, appealed to the religious pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) to help him set up a group focusing on racial justice. Though the FOR did not agree to directly sponsor the new organization, their Executive Secretary -- A.J. Muste, himself a minister and a former labor leader -- helped provide the basic support to birth the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Farmer had been FOR secretary for race relations; when he left FOR staff to create CORE, fellow FOR staff members Bayard Rustin and George Houser played a major support role.

The 1947 journey, then, an integrated trip through the upper South directly challenging the new rulings on bus travel, was formally sponsored by CORE, largely organized by FOR staffers Rustin and Houser and made up of a total of 16 men. Of the nine in the well-known photo, Rustin and four others--Igal Roodenko, Jim Peck, Wally Nelson and Ernest Bromley--ended up playing key roles in the leadership of the secular pacifist War Resisters League (WRL) in the decades to follow; Houser and Rustin co-authored the FOR-CORE report on the journey, We Challenged Jim Crow! For defying southern custom, the bus riders were arrested several times, with Rustin eventually authoring "22 Days on a Chain Gang," a much-read pamphlet on his experiences.

Having served as an organizer of various Free India activities in support of Gandhi and the independence movement, Rustin traveled to India in 1948 for a long-planned conference that ended up taking place shortly after Gandhi's assassination. Rustin and Sutherland also made regular contact with the burgeoning anti-colonial movements in Africa, with special emphasis on contacts in Nigeria and South Africa. In 1951, the two of them joined Houser in setting up the Committee to Support South African Resistance, which evolved into the American Committee on Africa, for four decades the key U.S. African solidarity network. Working with a small group of existing contacts within the War Resisters International, Sutherland was able to travel to the Gold Coast in 1953 -- the British colony that would soon achieve independence through nonviolent civil resistance, and change its name back to the historic kingdom long developed in that West African territory: Ghana. Sutherland remained in Africa for 50 years, an unofficial ambassador of revolutionary nonviolence working closely with the ideologically and tactically diverse liberation movements. But Rustin's life in 1953 was to take another turn: though never secretive about his sexuality, he was arrested in a car with two other men during a Quaker conference in Pasadena (in California, in part, to raise money for a planned trip to Nigeria). Charged with vagrancy and lewd conduct, he pled guilty to the single, lesser charge of "sex perversion," as consensual homosexual activity was referred to in California at that time.

Back in New York, the officers of FOR were worried about the reputation of the organization given the new attention which Rustin's arrest brought up regarding matters of sexual orientation. FOR policy regarding Rustin had been that he remain both quiet and abstinent -- refraining from discussing or engaging in any sexual activity whatsoever, publicly or privately. With the California "incident" suggesting an inability to comply with this policy, the FOR asked Rustin to resign from staff; Muste threatened Rustin with firing if he did not comply. His resignation was also marked by a letter of resignation from the Executive Committee of the War Resisters League, but the WRL refused to accept Rustin's stepping down. In a short period of time, in fact -- by August of 1953 -- the officers of the WRL (in many ways a sister organization to FOR) decided to offer Rustin a position on their staff, recognizing in him the talents that would later dazzle the young Martin Luther King, Jr. and a new generation of southern blacks looking to intensify the battle against segregation. WRL's process of hiring Rustin, however, was not without its own controversies.